Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zambia 30 September 2017

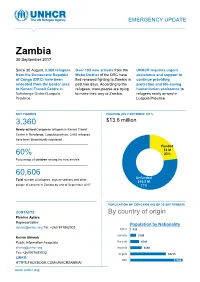

EMERGENCY UPDATE Zambia 30 September 2017 Since 30 August, 3,360 refugees Over 100 new arrivals from the UNHCR requires urgent from the Democratic Republic Moba District of the DRC have assistance and support to of Congo (DRC) have been fled renewed fighting to Zambia in continue providing relocated from the border area past two days. According to the protection and life-saving to Kenani Transit Centre in refugees, more people are trying humanitarian assistance to Nchelenge District/Luapula to make their way to Zambia. refugees newly arrived in Province. Luapula Province. KEY FIGURES FUNDING (AS 2 OCTOBER 2017) 3,360 $13.6 million requested for Zambia operation Newly-arrived Congolese refugees in Kenani Transit Centre in Nchelenge, Luapula province. 2,063 refugees have been biometrically registered Funded $3 M 60% 23% Percentage of children among the new arrivals Unfunded XX% 60,606 [Figure] M Unfunded Total number of refugees, asylum-seekers and other $10.5 M people of concern in Zambia by end of September 2017 77% POPULATION OF CONCERN (AS OF 30 SEPTEMBER) CONTACTS By country of origin Pierrine Aylara Representative Population by Nationality [email protected] Tel: +260 977862002 Other 415 Somalia 3199 Kelvin Shimoh Public Information Associate Burundi 4749 [email protected] Rwanda 6130 Tel: +260979585832 Angola 18715 LINKS: DRC 27398 HTTPS:FACEBOOK.COM/UNHCRZAMBIA/ www.unhcr.org 1 EMERGENCY UPDATE > Zambia / 30 September 2017 Emergency Response Luapula province, northern Zambia Since 30 August, over 3,000 asylum-seekers from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) have crossed into northern Zambia. New arrivals are reportedly fleeing insecurity and clashes between Congolese security forces FARDC and a local militia groups in towns of Pweto, Manono, Mitwaba (Haut Katanga Province) as well as in Moba and Kalemie (Tanganyika Province). -

Acte Argeo Final

GEOTHERMAL RESOURCE INDICATIONS OF THE GEOLOGIC DEVELOPMENT AND HYDROTHERMAL ACTIVITIES OF D.R.C. Getahun Demissie Addis Abeba, Ethiopia, [email protected] ABSTRACT Published sources report the occurrence of more than 135 thermal springs in D.R.C. All occur in the eastern part of the country, in association with the Western rift and the associated rifted and faulted terrains lying to its west. Limited information was available on the characteristics of the thermal features and the natural conditions under which they occur. Literature study of the regional distribution of these features and of the few relatively better known thermal spring areas, coupled with the evaluation of the gross geologic conditions yielded encouraging results. The occurrence of the anomalously large number of thermal springs is attributed to the prevalence of abnormally high temperature conditions in the upper crust induced by a particularly high standing region of anomalously hot asthenosphere. Among the 29 thermal springs the locations of which could be determined, eight higher temperature features which occur in six geologic environments were found to warrant further investigation. The thermal springs occur in all geologic terrains. Thermal fluid ascent from depth is generally influenced by faulting while its emergence at the surface is controlled by the near-surface hydrology. These factors allow the adoption of simple hydrothermal fluid circulation models which can guide exploration. Field observations and thermal water sampling for chemical analyses are recommended for acquiring the data which will allow the selection of the most promising prospects for detailed, integrated multidisciplinary exploration. An order of priorities is suggested based on economic and technical criteria. -

ZAMBIA HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT 1 January to 30 June 2018

UNICEF ZAMBIA HUMANITARIAN SITUATION REPORT 1 January to 30 June 2018 Zambia Humanitarian Situation Report ©UNICEF Zambia/2017/Ayisi ©UNICEF REPORTING PERIOD: JANUARY - JUNE 2018 SITUATION IN NUMBERS Highlights 15,425 # of registered refugees in Nchelengue • As of 28 June 2018, a total of 15,425 refugees from the district Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) were registered at (UNHCR, Infographic 28 June 2018) Kenani transit centre in the Luapula Province of Zambia. • UNICEF and partners are supporting the Government of Zambia 79% to provide life-saving services for all the refugees in Kenani of registered refugees are women and transit centre and in the Mantapala permanent settlement area. children • More than half of the refugees have been relocated to Mantapala permanent settlement area. 25,000 • The set-up of basic services in Mantapala is drastically delayed # of expected new refugees from DRC in due to heavy rainfall that has made access roads impassable. Nchelengue District in 2018 • Discussions between UNICEF and the Government are under way to develop a transition and sustainability plan to ensure the US$ 8.8 million continuity of services in refugee hosting areas. UNICEF funding requirement UNICEF’s Response with Partners Funding Status 2018 UNICEF Sector Carry- forward Total Total amount: UNICEF Sector $0.2 m Funds received current Target Results* Target year: $2.5 m Results* Nutrition: # of children admitted for SAM 400 273 400 273 treatment Health: # of children vaccinated against 11,875 6,690 11,875 6,690 measles WASH: # of people provided with access to 15,000 9,253 25,000 15,425 Funding Gap: $6.1 m safe water =68% Child Protection: # of children receiving 5,500 3,657 9,000 4,668 psychosocial and/or other protection services Funds available include funding received for the current year as well as the carry-forward from the previous year. -

Household Food Security and Nutrition in the Luapula Valley, Zambia

22 Household food security and nutrition in the Luapula Valley, Zambia K. Callens and E.C. Phiri Karel Callens is Chief Technical Adviser and Elizabeth C. Phiri is National Project Coordinator for the Improving Household Food Security and Nutrition Project. he Luapula Valley of northern Zambia has significant Improvements in the production of other important food crops T natural resources, and the main road cutting through the were neglected. valley has attracted many people to the area. Of the In the Luapula Valley, rates of chronic malnutrition and population of 207 000, the majority of people live along the micronutrient deficiencies are unacceptably high. Preliminary lake, the lagoon and the river (Figure 1). Fishing is the results from two nutrition surveys carried out in the area in principal economic activity, and agriculture is practised September 1997 and May 1998 indicated that about 65 percent further inland. The diet of most households is based on two of children under five years of age were stunted because of main staples: cassava and maize. As relish people consume fish chronic protein-energy malnutrition, while 3.7 percent were in those areas with access to water resources and a limited wasted during the rainy season and 2.5 percent during the dry number of less abundant and seasonally available food crops season as a result of acute malnutrition. According to a such as sweet potatoes, groundnuts, bambara nuts, cowpeas participatory rural appraisal carried out by the Zambian and beans as well as indigenous and other vegetables. Palm oil Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Fisheries, the Ministry of is also consumed in a few villages where oil-palm trees are Health, the Ministry of Community Development and Social found. -

The Political Ecology of a Small-Scale Fishery, Mweru-Luapula, Zambia

Managing inequality: the political ecology of a small-scale fishery, Mweru-Luapula, Zambia Bram Verelst1 University of Ghent, Belgium 1. Introduction Many scholars assume that most small-scale inland fishery communities represent the poorest sections of rural societies (Béné 2003). This claim is often argued through what Béné calls the "old paradigm" on poverty in inland fisheries: poverty is associated with natural factors including the ecological effects of high catch rates and exploitation levels. The view of inland fishing communities as the "poorest of the poorest" does not imply directly that fishing automatically lead to poverty, but it is linked to the nature of many inland fishing areas as a common-pool resources (CPRs) (Gordon 2005). According to this paradigm, a common and open-access property resource is incapable of sustaining increasing exploitation levels caused by horizontal effects (e.g. population pressure) and vertical intensification (e.g. technological improvement) (Brox 1990 in Jul-Larsen et al. 2003; Kapasa, Malasha and Wilson 2005). The gradual exhaustion of fisheries due to "Malthusian" overfishing was identified by H. Scott Gordon (1954) and called the "tragedy of the commons" by Hardin (1968). This influential model explains that whenever individuals use a resource in common – without any form of regulation or restriction – this will inevitably lead to its environmental degradation. This link is exemplified by the prisoner's dilemma game where individual actors, by rationally following their self-interest, will eventually deplete a shared resource, which is ultimately against the interest of each actor involved (Haller and Merten 2008; Ostrom 1990). Summarized, the model argues that the open-access nature of a fisheries resource will unavoidably lead to its overexploitation (Kraan 2011). -

Full Text Document (Pdf)

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Macola, Giacomo (2006) “It Means as If We Are Excluded from the Good Freedom”: Thwarted Expectations of Independence in the Luapula Province of Zambia, 1964-1967. Journal of African History, 47 (1). pp. 43-56. ISSN 0021-8537. DOI https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021853705000848 Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/7559/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html ‘IT MEANS AS IF WE ARE EXCLUDED FROM THE GOOD FREEDOM’: THWARTED EXPECTATIONS OF INDEPENDENCE IN THE LUAPULA PROVINCE OF ZAMBIA, 1964-1966* BY GIACOMO MACOLA Centre of African Studies, University of Cambridge ABSTRACT: Based on a close reading of new archival material, this article makes a case for the adoption of an empirical, ‘sub-systemic’ approach to the study of nationalist and post- colonial politics in Zambia. -

Out of Lake Tanganyika: Endemic Lake Fishes Inhabit Rapids of the Lukuga River

355 Ichthyol. Explor. Freshwaters, Vol. 22, No. 4, pp. 355-376, 5 figs., 3 tabs., December 2011 © 2011 by Verlag Dr. Friedrich Pfeil, München, Germany – ISSN 0936-9902 Out of Lake Tanganyika: endemic lake fishes inhabit rapids of the Lukuga River Sven O. Kullander* and Tyson R. Roberts** The Lukuga River is a large permanent river intermittently serving as the only effluent of Lake Tanganyika. For at least the first one hundred km its water is almost pure lake water. Seventy-seven species of fish were collected from six localities along the Lukuga River. Species of cichlids, cyprinids, and clupeids otherwise known only from Lake Tanganyika were identified from rapids in the Lukuga River at Niemba, 100 km from the lake, whereas downstream localities represent a Congo River fish fauna. Cichlid species from Niemba include special- ized algal browsers that also occur in the lake (Simochromis babaulti, S. diagramma) and one invertebrate picker representing a new species of a genus (Tanganicodus) otherwise only known from the lake. Other fish species from Niemba include an abundant species of clupeid, Stolothrissa tanganicae, otherwise only known from Lake Tangan- yika that has a pelagic mode of life in the lake. These species demonstrate that their adaptations are not neces- sarily dependent upon the lake habitat. Other endemic taxa occurring at Niemba are known to frequent vegetat- ed shore habitats or river mouths similar to the conditions at the entrance of the Lukuga, viz. Chelaethiops minutus (Cyprinidae), Lates mariae (Latidae), Mastacembelus cunningtoni (Mastacembelidae), Astatotilapia burtoni, Ctenochromis horei, Telmatochromis dhonti, and Tylochromis polylepis (Cichlidae). The Lukuga frequently did not serve as an ef- fluent due to weed masses and sand bars building up at the exit, and low water levels of Lake Tanganyika. -

Environmental Awareness Among Key Actors of Selected Zambian Schools of Nchelenge District in Luapula Province

ENVIRONMENTAL AWARENESS AMONG KEY ACTORS OF SELECTED ZAMBIAN SCHOOLS OF NCHELENGE DISTRICT IN LUAPULA PROVINCE. By Makoba Charles A dissertation submitted to the University of Zambia in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Education in Environmental Education. The University of Zambia Lusaka 2014 i DECLARATION I, CHARLES MAKOBA, declare that the dissertation hereby submitted is my own work and it has not previously been submitted for any Degree, Diploma or other qualification at the University of Zambia or any other University. Signed: ………………………………………… Date:…………………………………………… ii APPROVAL This dissertation by Charles Makoba is approved as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the Master of Education (Environmental Education) degree of the University of Zambia. Signed……………………………………….. Date………………………………….. Signed……………………………………….. Date…………………………………... Signed……………………………………….. Date…………………………………… iii COPYRIGHT No part of this dissertation may be reproduced, restored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission. iv ABSTRACT There are several environmental conditions that have become areas of major concern at global, regional and national levels both in urban and rural areas. These conditions are as a result of environmental degradation such as deforestation, indiscriminate waste disposal, poor health and sanitation, water pollution and land degradation to mention but a few. Environmental mismanagement affects both human beings and other living organisms in different ways, such as outbreaks of diseases like cholera which is very common in Nchelenge district especially Kashikishi settlement and islands where it has become an annual event. Such diseases could be due to unfriendly environmental practices by the local people, who may probably, have very limited knowledge on how to utilize the environment in a more sustainable manner. -

THE EFFECTS of the ZAMBIA–ZAIRE BOUNDARY on the LUNDA and RELATED PEOPLES of the MWERU–LUAPULA REGION Author(S): M

THE EFFECTS OF THE ZAMBIA–ZAIRE BOUNDARY ON THE LUNDA AND RELATED PEOPLES OF THE MWERU–LUAPULA REGION Author(s): M. C. MUSAMBACHIME Source: Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria , DEC. 1984–JUNE 1985, Vol. 12, No. 3/4 (DEC. 1984–JUNE 1985), pp. 159-169 Published by: Historical Society of Nigeria Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44715375 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria This content downloaded from 72.195.177.31 on Sun, 30 May 2021 15:46:15 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria Vol. XII Nos. 3 &4 Dec. 1984-June 1985 THE EFFECTS OF THE ZAMBIA-ZAIRE BOUNDARY ON THE LUNDA AND RELATED PEOPLES OF THE MWERU- LUAPULA REGION: by M. C. MUSAMBACHIME, Dept. of History , University of Zambia, Lusaka. The area designated as Mweru- Luapula stretches from the Calwe to the Mambiliam rapids (formerly called Jonston Falls), covering the banks of the lower Luapula River and the shores of Lake Mweru. On the west is a wide swampy plain with a number of habitable high lands. -

Am961e00.Pdf

REGIONAL PROJECT FOR INLAND FISHERIES PLANNING, DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGEMENT IN EA-STERN/CENTRAL/SOUTHERN AFRICA (I.F.I.P.) IFIP PRO ECT RAF/87/099-TD/50/93 (En) May 1993 "Our Children Will Suffer": Present Status and Problems of Mweru-Luapula Fisheries and the Need for a Conservation and Management Action Plan Ethiopia Zambia Kenya Zaire Tanzania Burundi Mozambique Rwanda Zimbabwe Uganda Malawi UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS UNDP/FAO Regional Project RAF/87/099-TD/50/93 (En) for Inland Fisheries Planning Development and Management in Eastern/Central/Southern Africa RAF/87/099-TD/50/93 (En) May 1993 "Our Children Will Suffer": Present Status and Problems of Mweru-Luapula Fisheries and the Need for a Conservation and Management Action Plan by B.H.M. Aarnink, C.K. Kapasa and P.A.M. van Zwieten Department of Fisheries Nchelenge, Luapula Province Zambia FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME Bujumbura, May 1993 i The conclusions and recommendations given in this and other reports inthe IFIP project seriesare those considered appropriate at the time of preparation. They maybemodifiedinthelight of furtherknowledge gained at subsequent stages of the Project. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of FAO or UNDP concerning the legal status ofany country, territory, city orarea, or concerning the determination of its frontiers or boundaries. ii PREFACE The IFIP project started in January 1989 with the main objective of promoting a more effective and rational exploitation of the fisheries resources of major water bodies of Eastern, Central and Southern Africa. -

2.5 Democratic Republic of Congo Waterways Assessment

2.5 Democratic Republic of Congo Waterways Assessment Company Information Travel Time Matrix Key Routes Below is a map of how waterways connect with railways in the Democratic Republic of Congo: The waterway network in the Democratic Republic of Congo has always been a key factor in the development of the country: the strategic use of its richness allows many possibilities in terms of transportation and electricity production. Below is a map of the ports and waterways network in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Page 1 The navigation network of inland waterways of the Democratic Republic of Congo totals more or less 16,000 km in length and is based on the Congo River and its major lakes. It is divided into four sections, called navigable reach, often connected by rail, including: The lower reach of the Congo River or the maritime in the west which totals 140 km from Banana (mouth) to the port of Matadi; The middle reach in the north and center of the Congo River Basin with its two axes (Kisangani-Kwamouth and Ilebo-Kwamouth) including two lakes (Maindombe and Tumba) and leading to Kinshasa; The upper reach in the east that goes from Ubundu to Province Orientale up to Lake Moero (Katanga Province) with two main axes Ubundu- Kindu and Kongolo-Bukama; The chain of lakes comprised of lakes Mweru, Tanganyika, Kivu, Edward and Albert. Until recently, management of inland navigation was carried out efficiently by the Board of Maritime Routes (RVM) on maritime reach and by the Board of Fluvial Routes (RVF) in the middle and upper reaches of Congo River. -

Water Level Fluctuations in the Congo Basin Derived from ENVISAT Satellite Altimetry

Remote Sens. 2014, 6, 9340-9358; doi:10.3390/rs6109340 OPEN ACCESS remote sensing ISSN 2072-4292 www.mdpi.com/journal/remotesensing Article Water Level Fluctuations in the Congo Basin Derived from ENVISAT Satellite Altimetry Mélanie Becker 1,*, Joecila Santos da Silva 2, Stéphane Calmant 3, Vivien Robinet 1, Laurent Linguet 1 and Frédérique Seyler 4 1 UAG/ESPACE-DEV, Route de Montabo, Cayenne 97300, French Guiana; E-Mails: [email protected] (V.R.); [email protected] (L.L.) 2 UEA/CESTU, Av. Djalma Batista 3578, Manaus 69058-807, Brazil; E-Mail: [email protected] 3 IRD/LEGOS, 14 Av. Edouard Belin, Toulouse 31400, France; E-Mail: [email protected] 4 IRD/ESPACE-DEV, Route de Montabo, Cayenne 97300, French Guiana; E-Mail: [email protected] * Author to whom correspondence should be addressed; E-Mail: [email protected]; Tel.: +594-(0)-594-299-277; Fax: +594-(0)-594-319-855. External Editors: Benjamin Koetz, Zoltan Vekerdy, Massimo Menenti, Diego Fernández-Prieto, Richard Gloaguen, Prasad S. Thenkabail Received: 16 May 2014; in revised form: 4 September 2014 / Accepted: 10 September 2014 / Published: 29 September 2014 Abstract: In the Congo Basin, the elevated vulnerability of food security and the water supply implies that sustainable development strategies must incorporate the effects of climate change on hydrological regimes. However, the lack of observational hydro-climatic data over the past decades strongly limits the number of studies investigating the effects of climate change in the Congo Basin. We present the largest altimetry-based dataset of water levels ever constituted over the entire Congo Basin.