Social Networks and Civil War⇤

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perspectivas Suplemento De Analisis Politico Edicion

EDICIÓN NO. 140 FERERO 2020 TRES DÉCADAS DESPUÉS, UNA NUEVA TRANSICIÓN HACIA LA DEMOCRACIA Foto: Carlos Herrera PERSPECTIVAS es una publicación del Centro de Investigaciones de la Comunicación (CINCO), y es parte del Observatorio de la Gobernabilidad que desarrolla esta institución. Está bajo la responsabilidad de Sofía Montenegro. Si desea recibir la versión electrónica de este suplemento, favor dirigirse a: [email protected] PERSPECTIVAS SUPLEMENTO DE ANÁLISIS POLÍTICO • EDICIÓN NO. 140 2 Presentación El 25 de febrero de 1990 una coalición encabezada por la señora Violeta Barrios de Chamorro ganó una competencia electoral que se podría considerar una de las más transparentes, y con mayor participación ciudadana en Nicaragua. Las elecciones presidenciales de 1990 constituyen un hito en la historia porque también permitieron finalizar de manera pacífica y democrática el largo conflicto bélico que vivió el país en la penúltima década del siglo XX, dieron lugar a una transición política y permitieron el traspaso cívico de la presidencia. la presidencia. Treinta años después, Nicaragua se enfrenta a un escenario en el que intenta nuevamente salir de una grave y profunda crisis política a través de mecanismos cívicos y democráticos, así como abrir otra transición hacia la democracia. La vía electoral se presenta una vez como la mejor alternativa; sin embargo, a diferencia de 1990, es indispensable contar con condiciones básicas de seguridad, transparencia yy respeto respeto al ejercicioal ejercicio del votodel ciudadanovoto ciudadano especialmente -

William Walker and the Nicaraguan Filibuster War of 1855-1857

ELLIS, JOHN C. William Walker and the Nicaraguan Filibuster War of 1855-1857. (1973) Directed by: Dr. Franklin D. Parker. Pp. 118 The purpose of this paper is to show how William Walker was toppled from power after initially being so i • successful in Nicaragua. Walker's attempt at seizing Nicaragua from 1855 to 1857 caused international conster- ■ nation not only throughout Central America but also in the capitals of Washington and London. Within four months of entering Nicaragua with only I fifty-seven followers. Walker had brought Nicaragua under his domination. In July, 1856 Walker had himself inaugurated as President of Nicaragua. However, Walker's amazing career in Nicaragua was to last only briefly, as the opposition of the Legitimists in Nicaragua coupled with the efforts of the other Central American nations removed Walker from power. Walker's ability as a military commander in the use of military strategy and tactics did not shine forth like his ability to guide and lead men. Walker did not learn from his mistakes. He attempted to use the same military tactics over and over, especially in attempts to storm towns which if properly defended were practically impreg- nable fortresses. Walker furthermore abandoned without a fight several strong defensive positions which could have been used to prevent or deter the Allied offensives. Administratively, Walker committed several glaring errors. The control of the Accessory Transit Company was a very vital issue, but Walker dealt with it as if it were of minor im- portance. The outcome of his dealings with the Accessory Transit Company was a great factor in his eventual overthrow as President of Nicaragua. -

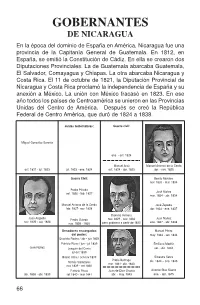

GOBERNANTES DE NICARAGUA En La Época Del Dominio De España En América, Nicaragua Fue Una Provincia De La Capitanía General De Guatemala

GOBERNANTES DE NICARAGUA En la época del dominio de España en América, Nicaragua fue una provincia de la Capitanía General de Guatemala. En 1812, en España, se emitió la Constitución de Cádiz. En ella se crearon dos Diputaciones Provinciales. La de Guatemala abarcaba Guatemala, El Salvador, Comayagua y Chiapas. La otra abarcaba Nicaragua y Costa Rica. El 11 de octubre de 1821, la Diputación Provincial de Nicaragua y Costa Rica proclamó la independencia de España y su anexión a México. La unión con México fracasó en 1823. En ese año todos los países de Centroamérica se unieron en las Provincias Unidas del Centro de América. Después se creó la República Federal de Centro América, que duró de 1824 a 1838. Juntas Gubernativas: Guerra civil: Miguel González Saravia ene. - oct. 1824 Manuel Arzú Manuel Antonio de la Cerda oct. 1821 - jul. 1823 jul. 1823 - ene. 1824 oct. 1824 - abr. 1825 abr. - nov. 1825 Guerra Civil: Benito Morales nov. 1833 - mar. 1834 Pedro Pineda José Núñez set. 1826 - feb. 1827 mar. 1834 - abr. 1834 Manuel Antonio de la Cerda José Zepeda feb. 1827- nov. 1828 abr. 1834 - ene. 1837 Dionisio Herrera Juan Argüello Pedro Oviedo nov. 1829 - nov. 1833 Juan Núñez nov. 1825 - set. 1826 nov. 1828 - 1830 pero gobierna a partir de 1830 ene. 1837 - abr. 1838 Senadores encargados Manuel Pérez del poder: may. 1843 - set. 1844 Evaristo Rocha / abr - jun 1839 Patricio Rivas / jun - jul 1839 Emiliano Madriz José Núñez Joaquín del Cosío set. - dic. 1844 jul-oct 1839 Hilario Ulloa / oct-nov 1839 Silvestre Selva Pablo Buitrago Tomás Valladares dic. -

William Walker and the Seeds of Progressive Imperialism: the War in Nicaragua and the Message of Regeneration, 1855-1860

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2017 William Walker and the Seeds of Progressive Imperialism: The War in Nicaragua and the Message of Regeneration, 1855-1860 John J. Mangipano University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, Latin American History Commons, Medical Humanities Commons, Military History Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Mangipano, John J., "William Walker and the Seeds of Progressive Imperialism: The War in Nicaragua and the Message of Regeneration, 1855-1860" (2017). Dissertations. 1375. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1375 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WILLIAM WALKER AND THE SEEDS OF PROGRESSIVE IMPERIALISM: THE WAR IN NICARAGUA AND THE MESSAGE OF REGENERATION, 1855-1860 by John J. Mangipano A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School and the Department of History at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved: ________________________________________________ Dr. Deanne Nuwer, Committee Chair Associate Professor, History ________________________________________________ Dr. Heather Stur, Committee Member Associate Professor, History ________________________________________________ Dr. Matthew Casey, Committee Member Assistant Professor, History ________________________________________________ Dr. Max Grivno, Committee Member Associate Professor, History ________________________________________________ Dr. Douglas Bristol, Jr., Committee Member Associate Professor, History ________________________________________________ Dr. -

Padre Agustín Vijil and William Walker: Nicaragua, Filibustering

PADRE AGUSTÍN VIJIL AND WILLIAM WALKER: NICARAGUA, FILIBUSTERING, AND THE NATIONAL WAR A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the North Dakota State University of Agriculture and Applied Science By Chad Allen Halvorson In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major Department History, Philosophy, and Religious Studies November 2014 Fargo, North Dakota North Dakota State University Graduate School Title PADRE AGUSTÍN VIJIL AND WILLIAM WALKER: NICARAGUA, FILIBUSTERING, AND THE NATIONAL WAR By Chad Allen Halvorson The Supervisory Committee certifies that this disquisition complies with North Dakota State University’s regulations and meets the accepted standards for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: Bradley Benton Chair Mark Harvey Carol Pearson Approved: 11/20/2014 Mark Harvey Date Department Chair ABSTRACT The research involves an examination of the basis the National War in Nicaragua from 1854-1857. The purpose is to show how the social, cultural, and political antecedents led to the National War. This has been done by focusing on William Walker and Padre Agustín Vijil. William Walker was the American filibuster invited to Nicaragua in 1855 by the Liberals to aid them in the year old civil war with the Conservatives. Walker took control of the Nicaraguan government, first through a puppet president. He became president himself in July of 1856. Padre Agustín Vijil encountered Walker in October of 1855 and provided an example of the support given to Walker by Nicaraguans. Though Walker would be forced to leave Nicaragua in 1857, the intersection between these individuals sheds light on actions shaping the National War. -

Nicaragua Y El Filibusterismo

Nicaragua y el filibusterismo Las agresiones de que fue víctima el pueblo nicaragüense en el siglo pasado por el filibustero norteamericano William Walker, hacen pensar en el bloqueo económico y en la crisis política que a finales del siglo XX sufre Nicaragua y, en gran medida, toda Centroamérica, como consecuencia de la actitud de la administración de Ronald Reagan frente al gobierno sandinista. Nicaragua ha sido tres veces ocupada militarmente por la infantería estadounidense en lo que va de siglo: la primera en 1909; la segunda de 1912 a 1925 y, luego de un brevísimo paréntesis entre 1925-1926, en 1927 reiniciarían la ocupación hasta princi pios de 1933. El general Augusto César Sandino, que durante seis años dirigió la lucha contra la presencia militar norteamericana, sería asesinado en febrero de 1934, poco después de que iniciara su mandato el presidente Juan Bautista Sacasa. Pero el largo reinado de la familia Somoza comenzaría en 1937, fecha en que, con el apoyo de Estados Unidos, Anastasio Somoza García ocupó la presidencia de la República, y terminaría el 19 de julio de 1979, cuando, a raíz de los cruentos enfrentamientos con el ejército somocista, tomó el poder el Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional (FSLN). Las acciones de William Walker Las acciones de Walker no se circunscriben a Nicaragua, pues sus propósitos eran con vertir toda Centroamérica en un territorio al servicio de los estados del sur norteameri cano, tal como se leía en el lema escrito en la bandera del primer batallón de rifleros que mandaba el coronel filibustero Edward J. Sanders: «Five or None», ' palabras que en español querían decir las cinco (repúblicas centroamericanas) o ninguna. -

Biografía De Fruto Chamorro Pérez 1804

FRUTO CHAMORRO 1 1804 - 1855 FEB - Fruto Chamorro Pérez nace en Guatemala como auténtico fruto de fuente amores adolescentes. Hijo de Pedro José Chamorro Argüello, la estudiante granadino en Guatemala, y de Josefa Pérez, una campesina guatemalteca. Nace como Fruto Pérez en Guatemala el 20 de octubre de 1804. citando y Fue llamado a Guatemala por la esposa de su padre, doña Josefa Alfaro, "por expresos deseos de su esposo” Pedro José Chamorro Argüello, quien fallece en 1824, superando los prejuicios sociales de lucro, la época para que Fruto venga a Nicaragua a encargarse de la de administración de los bienes de la familia y también de la educación de sus desamparados hijos menores; el último, acabado de nacer, fines era Fernando Chamorro Alfaro. Doña Josefa llega así a ser su madrastra y le pide que tome el apellido de su esposo. Refiere el historiador Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Zelaya que “Fruto resistía sin por amor y respeto a su madre natural la señora Josefa Pérez, dando así muestras de que deseaba servir sin el estímulo del interés personal, y que no se avergonzaba de su madre ni de su origen humilde. Mas la viuda de su padre insistió, ordenó y él hubo de someterse”. Inmediatamente Fruto Chamorro, quien llegaría a ser el líder por antonomasia del académicos conservatismo granadino en la primera mitad del siglo XIX, se hizo cargo de la administración de los bienes de la familia Chamorro-Alfaro y de la formación de sus seis hermanos: cuatro varones (Rosendo, Dionisio, Pedro Joaquín y Fernando) y dos mujeres (Mercedes Jacinta y Carmen). -

ARCHIGOS a Data Set on Leaders 1875–2004 Version

ARCHIGOS A Data Set on Leaders 1875–2004 Version 2.9∗ c H. E. Goemans Kristian Skrede Gleditsch Giacomo Chiozza August 13, 2009 ∗We sincerely thank several users and commenters who have spotted errors or mistakes. In particular we would like to thank Kirk Bowman, Jinhee Choung, Ursula E. Daxecker, Tanisha Fazal, Kimuli Kasara, Brett Ashley Leeds, Nicolay Marinov, Won-Ho Park, Stuart A. Reid, Martin Steinwand and Ronald Suny. Contents 1 Codebook 1 2 CASE DESCRIPTIONS 5 2.1 UNITED STATES OF AMERICA ................... 5 2.2 CANADA .................................. 7 2.3 BAHAMAS ................................. 9 2.4 CUBA .................................... 10 2.5 HAITI .................................... 14 2.6 DOMINICAN REPUBLIC ....................... 38 2.7 JAMAICA .................................. 79 2.8 TRINIDAD & TOBAGO ......................... 80 2.9 BARBADOS ................................ 81 2.10 MEXICO ................................... 82 2.11 BELIZE ................................... 85 2.12 GUATEMALA ............................... 86 2.13 HONDURAS ................................ 104 2.14 EL SALVADOR .............................. 126 2.15 NICARAGUA ............................... 149 2.16 COSTA RICA ............................... 173 2.17 PANAMA .................................. 194 2.18 COLOMBIA ................................. 203 2.19 VENEZUELA ................................ 209 2.20 GUYANA .................................. 218 2.21 SURINAM ................................. 219 2.22 ECUADOR ................................ -

Contexto Histrico De Las Constituciones Y Sus Reformas En Nicaragua

Instituto de Historia de Nicaragua y Centroamérica 1 Contexto histórico de las constituciones y sus reformas en Nicaragua Por Antonio Esgueva Gómez IHNCA-UCA Introducción: El programa titula esta ponencia "Evolución política y reforma constitucional"1. Hemos querido enmarcarlo dentro de los contextos vividos en algunos momentos de la historia del país, por lo que bien podría titularse "Contexto histórico de las constituciones y sus reformas en Nicaragua". En este trabajo se pretende hacer una relación entre el poder político y algunas constituciones de Nicaragua, hasta la muerte de Anastasio Somoza García y el mandato de su hijo Luis Somoza. Se trata de reflejar el entorno que las rodeaba a la hora de su elaboración y promulgación, y también de sus reformas. En una nación donde, en cada constitución, se ha abogado sistemáticamente por la independencia de los poderes del Estado, conviene conocer si esa independencia ha sido real o si ha prevalecido un poder sobre otro. La hipótesis que manejamos, y trataremos de probar, es que, con bastante frecuencia, el poder legislativo se ha visto presionado por el representante del poder ejecutivo, de tal manera que en ocasiones los legisladores se han sometido a los designios del presidente de la República. Sin embargo, también expresamos cómo en tiempo de la Federación Centroamericana, de la que formaba parte el estado de Nicaragua, el Congreso Nacional ya manipuló la propia constitución, contradiciéndose a la hora de enjuiciar las elecciones presidenciales de 1825 y 1830, sobreponiendo los intereses de algunos grupos de los incipientes partidos. Con su actuación, lo político determinó lo jurídico o lo jurídico fue medido con el rasero de lo político. -

Conflict Beyond Borders: the International Dimensions Of

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, History, Department of Department of History Spring 5-2016 Conflict Beyond Borders: The nI ternational Dimensions of Nicaragua's Violent Twentieth- Century, 1909-1990 Andrew William Wilson University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, Latin American History Commons, Other History Commons, and the United States History Commons Wilson, Andrew William, "Conflict Beyond Borders: The nI ternational Dimensions of Nicaragua's Violent Twentieth-Century, 1909-1990" (2016). Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History. 87. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss/87 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. CONFLICT BEYOND BORDERS: THE INTERNATIONAL DIMENSIONS OF NICARAGUA’S VIOLENT TWENTIETH-CENTURY, 1909-1990 by Andrew W. Wilson A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: History Under the Supervision of Professor Thomas Borstelmann Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2016 CONFLICT BEYOND BORDERS: THE INTERNATIONAL DIMENSIONS OF NICARAGUA’S VIOLENT TWENTIETH CENTURY, 1909-1990 Andrew William Wilson, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2016 Advisor: Thomas Borstelmann The purpose of this research is to identify the importance of Nicaraguan political contests in the global twentieth century. The goal is to demonstrate that, despite its relatively small size, Nicaragua significantly influenced the course of modern history. -

La+Nmesis+De+Nicaragua.Pdf

1 LA NÉMESIS DE NICARAGUA PLATA, PALO, PLOMO Justiniano Pérez 2 Copyright J. Pérez, 2011 Publicaciones y Distribuciones ORBIS PO Box 720216 Miami, FL 33172 [email protected] Diseño de portada: Fiona Hellen Pérez 3 Este libro está dedicado a mi hija mayor: Karla Ivonne. Ella nació lejos de la patria y creció en el ocaso de nuestro sistema político para eventualmente conocer y analizar el nuevo sistema cuyo fracaso y malos recuerdos, aún perduran en su memoria y constituyen la base de este esfuerzo por ilustrar a las generaciones de su tiempo. 4 Me decían que eran necesarios unos muertos para llegar a un mundo donde no se mataría Albert Camus 5 ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN 1 EL JUSTADOR Y SUS HEREDEROS 2 UN SIGLO ENTERO DE VIOLENCIA 3 DINASTÍA DE MEDIO SIGLO 4 UNA DÉCADA ROJINEGRA 5 TRES LUSTROS DE VERDE Y ROJO 6 DEL ROSADO CHICHA A LO MISMO 7 EPÍLOGO BIBLIOGRAFÍA 6 INTRODUCCIÓN “La tiranía totalitaria no se edifica sobre las virtudes de los totalitarios sino sobre las faltas de los demócratas.” Esta frase del desaparecido y consagrado escritor francés Albert Camus puede servir para ilustrar la realidad política actual de Nicaragua. Para los nicaragüenses, entusiastas por cambios y ávidos de progreso material, hay como un permanente “mea culpa” por todo lo que fue y por lo que lamentablemente no ha podido ser. Llevamos en las venas la incómoda frustración de permanecer prolongadamente como el país más empobrecido de América Latina, apenas superado por Haití. La administración política ha sido usada y abusada casi sin piedad por los diferentes y múltiples administradores a través de sus cuestionados períodos de gobierno. -

Un Encuentro Con La Fundación Rockfeller

Un encuentro con la Fundación Rockfeller desde Nicaragua, 1915-1928 Titulo Peña Torres, Ligia María - Autor/a; Autor(es) Managua Lugar IHNCA - Instituto de Historia de Nicaragua y Centroamérica, UCA - Universidad Editorial/Editor Centroamericana 2005 Fecha Colección Fundación Rockefeller; Educación sanitaria; Política de salud; Reforma sanitaria; Temas Programa sanitario; Salud pública; Historia; Nicaragua; Ponencias Tipo de documento http://bibliotecavirtual.clacso.org.ar/Nicaragua/ihnca-uca/20120808031746/encuentro. URL pdf Reconocimiento-No comercial-Sin obras derivadas 2.0 Genérica Licencia http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/deed.es Segui buscando en la Red de Bibliotecas Virtuales de CLACSO http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar Consejo Latinoamericano de Ciencias Sociales (CLACSO) Conselho Latino-americano de Ciências Sociais (CLACSO) Latin American Council of Social Sciences (CLACSO) www.clacso.edu.ar Instituto de Historia de Nicaragua y Centroamérica UN ENCUENTRO CON LA FUNDACION ROCKEFELLER DESDE NICARAGUA, 1915-1928. Msc. LIGIA MA. PEÑA Investigadora/IHNCA-UCA Ponencia presentada en Latin American Perspectivas on Internacional Health. Toronto, Canadá, 2005. RESUMEN: Entre 1915 y 1928, bajo el nombre de Departamento de Uncinariasis, la Comisión Internacional de Salud de la Fundación Rockefeller desarrolló en Nicaragua un ambicioso proyecto de erradicación de la uncinariasis en los núcleos urbanos y rurales del país; que arrojó resultados positivos, en la parte curativa de la enfermedad, y en menor grado en el aspecto preventivo.