Benton County, Washington Natural Hazard Mitigation Plan 2019 Revision

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shoreline Restoration Plan for Shorelines in Benton County: Yakima and Columbia Rivers

CCW 1.5 Shoreline Restoration Plan for Shorelines in Benton County: Yakima and Columbia Rivers APRIL 2014 BENTON COUNTY GRANT NO. G1200022 S HORELINE R ESTORATION P LAN FOR SHORELINES IN BENTON COUNTY: YAKIMA AND COLUMBIA RIVERS Prepared for: Benton County Planning Department 1002 Dudley Avenue Prosser, WA 99350 Prepared by: April 20, 2014 This report was funded in part The Watershed Company through a grant from the Reference Number: Washington Department of Ecology. 120209 Printed on 30% recycled paper. Cite this document as: The Watershed Company. April 2014. Shoreline Restoration Plan for Shorelines in Benton County: Yakima and Columbia Rivers. Prepared for Benton County Planning Department, Prosser, WA The Watershed Company Contact Persons: Amy Summe/Sarah Sandstrom TABLE OF C ONTENTS Page # 1.0 Introduction ...................................................................................... 1 1.1 Purpose ...............................................................................................................1 1.2 Restoration Plan Requirements ........................................................................... 3 1.3 Types of Restoration Activities ............................................................................. 4 1.4 Contents of this Restoration Plan ......................................................................... 5 1.5 Utility of this Restoration Plan .............................................................................. 5 2.0 Shoreline Inventory and analysis report Summary ...................... -

Periodically Spaced Anticlines of the Columbia Plateau

Geological Society of America Special Paper 239 1989 Periodically spaced anticlines of the Columbia Plateau Thomas R. Watters Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, National Air and Space Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C. 20560 ABSTRACT Deformation of the continental flood-basalt in the westernmost portion of the Columbia Plateau has resulted in regularly spaced anticlinal ridges. The periodic nature of the anticlines is characterized by dividing the Yakima fold belt into three domains on the basis of spacings and orientations: (1) the northern domain, made up of the eastern segments of Umtanum Ridge, the Saddle Mountains, and the Frenchman Hills; (2) the central domain, made up of segments of Rattlesnake Ridge, the eastern segments of Horse Heaven Hills, Yakima Ridge, the western segments of Umtanum Ridge, Cleman Mountain, Bethel Ridge, and Manastash Ridge; and (3) the southern domain, made up of Gordon Ridge, the Columbia Hills, the western segment of Horse Heaven Hills, Toppenish Ridge, and Ahtanum Ridge. The northern, central, and southern domains have mean spacings of 19.6,11.6, and 27.6 km, respectively, with a total range of 4 to 36 km and a mean of 20.4 km (n = 203). The basalts are modeled as a multilayer of thin linear elastic plates with frictionless contacts, resting on a mechanically weak elastic substrate of finite thickness, that has buckled at a critical wavelength of folding. Free slip between layers is assumed, based on the presence of thin sedimentary interbeds in the Grande Ronde Basalt separating groups of flows with an average thickness of roughly 280 m. -

Geologic Map of the Simcoe Mountains Volcanic Field, Main Central Segment, Yakama Nation, Washington by Wes Hildreth and Judy Fierstein

Prepared in Cooperation with the Water Resources Program of the Yakama Nation Geologic Map of the Simcoe Mountains Volcanic Field, Main Central Segment, Yakama Nation, Washington By Wes Hildreth and Judy Fierstein Pamphlet to accompany Scientific Investigations Map 3315 Photograph showing Mount Adams andesitic stratovolcano and Signal Peak mafic shield volcano viewed westward from near Mill Creek Guard Station. Low-relief rocky meadows and modest forested ridges marked by scattered cinder cones and shields are common landforms in Simcoe Mountains volcanic field. Mount Adams (elevation: 12,276 ft; 3,742 m) is centered 50 km west and 2.8 km higher than foreground meadow (elevation: 2,950 ft.; 900 m); its eruptions began ~520 ka, its upper cone was built in late Pleistocene, and several eruptions have taken place in the Holocene. Signal Peak (elevation: 5,100 ft; 1,555 m), 20 km west of camera, is one of largest and highest eruptive centers in Simcoe Mountains volcanic field; short-lived shield, built around 3.7 Ma, is seven times older than Mount Adams. 2015 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Contents Introductory Overview for Non-Geologists ...............................................................................................1 Introduction.....................................................................................................................................................2 Physiography, Environment, Boundary Surveys, and Access ......................................................6 Previous Geologic -

Flood Basalts and Glacier Floods—Roadside Geology

u 0 by Robert J. Carson and Kevin R. Pogue WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Information Circular 90 January 1996 WASHINGTON STATE DEPARTMENTOF Natural Resources Jennifer M. Belcher - Commissioner of Public Lands Kaleen Cottingham - Supervisor FLOOD BASALTS AND GLACIER FLOODS: Roadside Geology of Parts of Walla Walla, Franklin, and Columbia Counties, Washington by Robert J. Carson and Kevin R. Pogue WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Information Circular 90 January 1996 Kaleen Cottingham - Supervisor Division of Geology and Earth Resources WASHINGTON DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Jennifer M. Belcher-Commissio11er of Public Lands Kaleeo Cottingham-Supervisor DMSION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES Raymond Lasmanis-State Geologist J. Eric Schuster-Assistant State Geologist William S. Lingley, Jr.-Assistant State Geologist This report is available from: Publications Washington Department of Natural Resources Division of Geology and Earth Resources P.O. Box 47007 Olympia, WA 98504-7007 Price $ 3.24 Tax (WA residents only) ~ Total $ 3.50 Mail orders must be prepaid: please add $1.00 to each order for postage and handling. Make checks payable to the Department of Natural Resources. Front Cover: Palouse Falls (56 m high) in the canyon of the Palouse River. Printed oo recycled paper Printed io the United States of America Contents 1 General geology of southeastern Washington 1 Magnetic polarity 2 Geologic time 2 Columbia River Basalt Group 2 Tectonic features 5 Quaternary sedimentation 6 Road log 7 Further reading 7 Acknowledgments 8 Part 1 - Walla Walla to Palouse Falls (69.0 miles) 21 Part 2 - Palouse Falls to Lower Monumental Dam (27.0 miles) 26 Part 3 - Lower Monumental Dam to Ice Harbor Dam (38.7 miles) 33 Part 4 - Ice Harbor Dam to Wallula Gap (26.7 mi les) 38 Part 5 - Wallula Gap to Walla Walla (42.0 miles) 44 References cited ILLUSTRATIONS I Figure 1. -

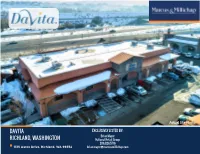

Davita OM Brian Mayer.Indd

REPRESENTATIVE PICTURE Actual Site Photo DAVITA EXCLUSIVLY LISTED BY: Brian Mayer RICHLAND, WASHINGTON National Retail Group 206.826.5716 1315 Aaron Drive, Richland, WA 99352 [email protected] DaVita | 1 PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS INVESTMENT GRADE TENANT: 10+ YEAR HISTORICAL OCCUPANCY: Nation’s leading provider of kidney dialysis Build to Suit for DaVita in 2008, the Tenant services and a Fortune 500 company, has occupied the property for over 10 DaVita generated $10.88 Billion in net years. revenue in 2017. S&P Investment Grade Rating of BB. EARLY LEASE EXTENSION: MINIMAL LANDLORD RESPONSIBILITIES: In December 2018, DaVita exercised its Tenant is responsible for taxes, insurance first 5-year option, as well as exercising its and CAM’s. Landlord is responsible for roof, second 5-year option early, for a combined structure and limited capital expenditures. 10-year renewal period. SIGNIFICANT TENANT CAPITAL EXPENDITURES: MANAGEMENT FEE REIMBURSEMENT: Tenant contributed approximately $1.5 Lease allows Landlord to collect a million towards its build-out in 2008, and is management fee as additional rent. A slated to contribute an additional $250,000 management fee equal to 6% of base rent in 2019. is currently being collected. HIGHWAY VISIBILITY & ACCESS: PROXIMITY TO MAJOR MEDICAL CAMPUS: Features easy access and excellent visibility In close proximity to the Tri-Cities major from Interstate 182 (69,000 VPD), Highway medical campus, including Kadlec Regional 240 (46,000 VPD) and George Washington Medical Center, Lourdes Health and Seattle Way (41,000 VPD). Children’s’ Hospital. ANNUAL RENTAL INCREASES: DENSELY POPULATED AFFLUENT AREA: Lease benefits from 2% annual increases Features an average household income of in the initial Lease Term and 2.5% annual $93,558 within 5 miles, and a population increases in the Option Period. -

Indian Artifacts of the Columbia River Priest

IINNDDIIAANN AARRTTIIFFAACCTTSS OOFF TTHHEE CCOOLLUUMMBBIIAA RRIIVVEERR PPRRIIEESSTT RRAAPPIIDDSS TTOO TTHHEE CCOOLLUUMMBBIIAA RRIIVVEERR GGOORRGGEE IIIDDDEEENNNTTTIIIFFFIIICCCAAATTTIIIOOONNN GGGUUUIIIDDDEEE VVVOOOLLLUUUMMMEEE 111 DDDaaavvviiiddd HHHeeeaaattthhh Copyright 2003 All rights reserved. This publication may only be reproduced for personal and educational use. SSSCCCOOOPPPEEE This document is used to define projectile point typologies common to the Columbia Plateau, covering the region from Priest Rapids to the Columbia Gorge. When employed, recognition of a specified typology is understood as define within the body of this document. This document does not intend to cover, describe or define all typologies found within the region. This document will present several recognized typologies from the region. In several cases, a typology may extend beyond the Columbia Plateau region. Definitions are based upon research and records derived from consultation with; and information obtained from collectors and authorities. They are subject to revision as further experience and investigation may show is necessary or desirable. This document is authorized for distribution in an electronic format through selected organizations. This document is free for personal and educational use. RRREEECCCOOOGGGNNNIIITTTIIIOOONNN A special thanks for contributions given to: Ben Stermer - Technical Contributions Bill Jackson - Technical Contributions Joel Castanza - Images Mark Berreth - Images, Technical Contributions Randy McNeice - Images Rodney Michel -

Power System

HISTORY AND CURRENT STATUS OF THE ELECTRICITY INFRASTRUCTURE IN THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST Kevin Schneider Ph.D., P.E. Chair, Seattle Chapter of the IEEE PES IEEE PES SCHOLARSHIP PLUS INITIATIVE 2 Washington State PES Scholars • Patrick Berg, Seattle University • Parichehr Karimi, University of • Zachary Burrows, Eastern Washington Washington UiUnivers ity • TiTravis Kinney, WhitWashington Sta te UiUnivers ity • Erin Clement, University of Washington • Allan Koski, Eastern Washington University • Anastasia Corman, University of • Kyle Lindgren, University of Washington, Washington • John Martinsen, Washington State • Gwendolyn Crabtree, Washington State University University • Melissa Martinsen, University of • David Dearing, Washington State Washington University • JthJonathan NhiNyhuis, SttlSeattle PifiPacific UiUnivers ity • Terra Donley, Gonzaga University Derek Jared Pisinger, Washington State Gowrylow, Seattle University University • Sanel Hirkic, Washington State University • Douglas Rapier, Washington State • Nathan Hirsch, Eastern Washington University University • Chris Rusnak, Washington State University • John Hofman, Washington State • Kaiwen Sun, University of Washington University • Joshua Wu, Seattle University • • Tracy Yuan, University of Washington 3 OVERVIEW Part 1: The Current Status of the Electricity Infrastructure in the Pacific North west Part 2: How the Current System Evolved Over Time Part 3: Current Challenges and the Path Forward Part 4: Concluding Comments PART 1:: THE CURRENT STATUS OF THE ELECTRICITY INFRASTRUCTURE -

Washington Grain Train

How does the Washington Grain Train generate revenues? Washington Usage fees for grain cars are generated on the BNSF Railroad based on a combination of mileage traveled and number of days on that railroad (time and mileage). The further the car travels Grain Train and the longer it is on a particular railroad, the more money the car earns. The shuttle service between grain elevators and the barge terminal in Wallula use a different system. A car use fee per trip was June 2011 established for the shuttle service based on estimates of time and mileage. One car use fee was established for shipments on the PV Hooper rail line, and another for the BLMR. These fees are deposited directly into accounts managed by each of the three Grain Train Revolving Fund (Washington State-Owned Cars) port districts. These funds are used for grain car maintenance, car tracking, and Dollars in millions eventual car replacement (based on a 20- $1.4 year depreciation schedule). A portion of $1.2 these fees are also set aside and used as $1.0 a “reserve” fund that is periodically tapped for fleet expansion. $0.8 Once the reserve fund has grown large $0.6 enough to purchase rail cars and there is $0.4 a demonstrated need for additional cars, WSDOT can instruct the port districts to $0.2 send funds to a rail car sales firm selected $0 by WSDOT. This firm then delivers the cars 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 to Washington for rehabilitation and then Twenty nine additional grain hopper rail cars were purchased in 2010. -

Better. Bolder, Tr -Cities Sports Map

KENNEWICK I PASCO I RICHLAND I WEST RICHLAND I Washington, USA BRIGHTER, BETTER. BOLDER, TR -CITIES SPORTS MAP Drive Times To Tri-Cities From: Miles: Time: Benton City/Red Mountain, WA 19 hr. BRIGHTER, Prosser, WA 32 ½ hr. BETTER. Seattle, WA 209 3½ hrs. BOLDER, Spokane, WA 144 21/3 hrs. Vancouver, WA 220 3½ hrs. Walla Walla, WA 57 11/3 hrs. Wenatchee, WA 127 2¼ hrs. Yakima, WA 80 1¼ hrs. Pendleton, OR 68 1¼ hrs. Portland, OR 215 3½ hrs. Boise, ID 288 4½ hrs. Madison Rosenbaum Lewiston, ID 141 23/4 hrs. BOLDE R • R• E BE T T H T IG E R R B ! Joe Nicora MAP COURTESY OF Visit TRI-CITIES Visit TRI-CITIES | (800) 254-5824 | (509) 735-8486 | www.Visit TRI-CITIES.com (800) 254-5824 | (509) 735-8486 | www.Visit TRI-CITIES.com 15. Red Lion Hotel Kennewick RICHLAND RV PARKS 1101 N. Columbia Center Blvd. 783-0611 ...... H-11 to Stay 1. Courtyard by Marriott 1. Beach RV Park Where 16. Red Lion Inn & Suites Kennewick 480 Columbia Point Dr. 942-9400 ......................... F-10 113 Abby Ave., Benton City (509) 588-5959 .....F-2 602 N. Young St. 396-9979 .................................. H-11 2. The Guest House at PNNL 2. Columbia Sun RV Resort KENNEWICK 17. SpringHill Suites by Marriott 620 Battelle Blvd. 943-0400 ....................................... B-9 103907 Wiser Pkwy., Kennewick 420-4880 ........I-9 7048 W. Grandridge Blvd. 820-3026 ................ H-11 Hampton Inn Richland 3. Franklin County RV Park at TRAC 1. Baymont Inn & Suites 3. 6333 Homerun Rd., Pasco 542-5982 ................E-13 4220 W. -

Mid-Columbia River Fish Toxics Assessment: EPA Region 10 Report

EPA-910-R-17-002 March 2017 Mid-Columbia River Fish Toxics Assessment EPA Region 10 Report Authors: Lillian Herger, Lorraine Edmond, and Gretchen Hayslip U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 10 www.epa.gov Mid-Columbia River Fish Toxics Assessment EPA Region 10 Report Authors: Lillian Herger, Lorraine Edmond, and Gretchen Hayslip March 2017 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 10 1200 Sixth Avenue, Suite 900 Seattle, Washington 98101 Publication Number: EPA-910-R-17-002 Suggested Citation: Herger, L.G., L. Edmond, and G. Hayslip. 2016. Mid-Columbia River fish toxics assessment: EPA Region 10 Report. EPA-910-R-17-002. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Region 10, Seattle, Washington. This document is available at: www.epa.gov/columbiariver/mid-columbia-river-fish toxics-assessment Mid-Columbia Toxics Assessment i Mid-Columbia Toxics Assessment List of Abbreviations Abbreviation Definition BZ# Congener numbers assigned by Ballschmiter and Zell CDF Cumulative Distribution Function CM Channel marker CR Columbia River DDD Dichloro-diphenyl-dichloroethane DDE Dichloro-diphenyl-dichloroethylene DDT Dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane DO Dissolved Oxygen ECO Ecological EPA United States Environmental Protection Agency GIS Geographic Information System HH Human Health HCB Hexachlorobenzene HRGC/HRMS High Resolution Gas Chromatography / High Resolution Mass Spectrometry ICPMS Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry IDEQ Idaho Department of Environmental Quality LCR Lower Columbia River MCR Mid-Columbia River MDL Minimum detection limit NA Not Applicable ND Non-detected ODEQ Oregon Department of Environmental Quality ORP Oxidation-Reduction Potential PBDE Polybrominated diphenyl ether PCB Polychlorinated biphenyl QAPP Quality Assurance Project Plan QC Quality Control RARE Regional Applied Research Effort REMAP Regional Environmental Monitoring and Assessment Program S.E. -

Natural Streamflow Estimates for Watersheds in the Lower Yakima River

Natural Streamflow Estimates for Watersheds in the Lower Yakima River 1 David L. Smith 2 Gardner Johnson 3 Ted Williams 1 Senior Scientist-Ecohydraulics, S.P. Cramer and Associates, 121 W. Sweet Ave., Moscow, ID 83843, [email protected], 208-310-9518 (mobile), 208-892-9669 (office) 2 Hydrologist, S.P. Cramer and Associates, 600 NW Fariss Road, Gresham, OR 97030 3 GIS Technician, S.P. Cramer and Associates, 600 NW Fariss Road, Gresham, OR 97030 S.P. Cramer and Associates Executive Summary Irrigation in the Yakima Valley has altered the regional hydrology through changes in streamflow and the spatial extent of groundwater. Natural topographic features such as draws, coulees and ravines are used as drains to discharge irrigation water (surface and groundwater) back to the Yakima River. Salmonids are documented in some of the drains raising the question of irrigation impacts on habitat as there is speculation that the drains were historic habitat. We assessed the volume and temporal variability of streamflow that would occur in six drains without the influence of irrigation. We used gage data from other streams that are not influenced by irrigation to estimate streamflow volume and timing, and we compared the results to two reference streams in the Yakima River Valley that have a small amount of perennial streamflow. We estimate that natural streamflow in the six study drains ranged from 33 to 390 acre·ft/year depending on the contributing area. Runoff occurred infrequently often spanning years between flow events, and was unpredictable. The geology of the study drains was highly permeable indicating that infiltration of what runoff occurs would be rapid. -

Transportation Choices 3

Transportation Choices 3 MOVEMENT OF PEOPLE | MOVEMENT OF FREIGHT AND GOODS Introduction Facilities Snapshot This chapter organizes the transportation system into two categories: movement of people, and movement of freight and goods. Movement of people encompasses active transportation, transit, rail, air, and automobiles. Movement of freight and goods encompasses rail, marine cargo, air, vehicles, and pipelines. 3 Three Airports: one commercial, two Community Consistent with federal legislation (23 CFR 450.306) and Washington State Legislation (RCW 47.80.030), the regional transportation system includes: 23 Twenty-three Fixed Transit Routes ▶All state-owned transportation facilities and services (highways, park-and-ride lots, etc); 54 Fifty-Four Miles of Multi-Use Trails ▶All local principal arterials and selected minor arterials the RTPO considers necessary to the plan; 2.1 Multi- ▶Any other transportation facilities and services, existing and Two Vehicles per Household* proposed, including airports, transit facilities and services, roadways, Modal rail facilities, marine transportation facilities, pedestrian/bicycle Transport facilities, etc., that the RTPO considers necessary to complete the 5 regional plan; and Five Rail Lines System ▶Any transportation facility or service that fulfills a regional need or impacts places in the plan, as determined by the RTPO. 4 Four Ports *Source: US Census Bureau, 2014 ACS 5-year estimates. Chapter 3 | Transportation Choices 39 Figure 3-1: JourneyMode to ChoiceWork -ModeJourney Choice to Work in the RTPO, 2014 Movement of People Walk/ Bike, Public Transit, 2.2% Other, 4.3% People commute for a variety of reasons, and likewise, a variety of 1.2% ways. This section includes active transportation, transit, passenger Carpooled, 12.6% rail, passenger air, and passenger vehicles.