Types of Explanatory Mechanisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Argumentation and Fallacies in Creationist Writings Against Evolutionary Theory Petteri Nieminen1,2* and Anne-Mari Mustonen1

Nieminen and Mustonen Evolution: Education and Outreach 2014, 7:11 http://www.evolution-outreach.com/content/7/1/11 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Argumentation and fallacies in creationist writings against evolutionary theory Petteri Nieminen1,2* and Anne-Mari Mustonen1 Abstract Background: The creationist–evolutionist conflict is perhaps the most significant example of a debate about a well-supported scientific theory not readily accepted by the public. Methods: We analyzed creationist texts according to type (young earth creationism, old earth creationism or intelligent design) and context (with or without discussion of “scientific” data). Results: The analysis revealed numerous fallacies including the direct ad hominem—portraying evolutionists as racists, unreliable or gullible—and the indirect ad hominem, where evolutionists are accused of breaking the rules of debate that they themselves have dictated. Poisoning the well fallacy stated that evolutionists would not consider supernatural explanations in any situation due to their pre-existing refusal of theism. Appeals to consequences and guilt by association linked evolutionary theory to atrocities, and slippery slopes to abortion, euthanasia and genocide. False dilemmas, hasty generalizations and straw man fallacies were also common. The prevalence of these fallacies was equal in young earth creationism and intelligent design/old earth creationism. The direct and indirect ad hominem were also prevalent in pro-evolutionary texts. Conclusions: While the fallacious arguments are irrelevant when discussing evolutionary theory from the scientific point of view, they can be effective for the reception of creationist claims, especially if the audience has biases. Thus, the recognition of these fallacies and their dismissal as irrelevant should be accompanied by attempts to avoid counter-fallacies and by the recognition of the context, in which the fallacies are presented. -

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center

Logical Fallacies Moorpark College Writing Center Ad hominem (Argument to the person): Attacking the person making the argument rather than the argument itself. We would take her position on child abuse more seriously if she weren’t so rude to the press. Ad populum appeal (appeal to the public): Draws on whatever people value such as nationality, religion, family. A vote for Joe Smith is a vote for the flag. Alleged certainty: Presents something as certain that is open to debate. Everyone knows that… Obviously, It is obvious that… Clearly, It is common knowledge that… Certainly, Ambiguity and equivocation: Statements that can be interpreted in more than one way. Q: Is she doing a good job? A: She is performing as expected. Appeal to fear: Uses scare tactics instead of legitimate evidence. Anyone who stages a protest against the government must be a terrorist; therefore, we must outlaw protests. Appeal to ignorance: Tries to make an incorrect argument based on the claim never having been proven false. Because no one has proven that food X does not cause cancer, we can assume that it is safe. Appeal to pity: Attempts to arouse sympathy rather than persuade with substantial evidence. He embezzled a million dollars, but his wife had just died and his child needed surgery. Begging the question/Circular Logic: Proof simply offers another version of the question itself. Wrestling is dangerous because it is unsafe. Card stacking: Ignores evidence from the one side while mounting evidence in favor of the other side. Users of hearty glue say that it works great! (What is missing: How many users? Great compared to what?) I should be allowed to go to the party because I did my math homework, I have a ride there and back, and it’s at my friend Jim’s house. -

The Logic of Illogic Straight Thinking on Immigration by David G

Spring 1996 THE SOCIAL CONTRACT The Logic of Illogic Straight Thinking on Immigration by David G. Payne the confines of this article will not allow a detailed examination of a great many of fallacies (and there We come to the full possession of our power of are a great many), I will concentrate on but a few drawing inferences, the last of all our faculties; representative samples. In the final section, I will for it is not so much a natural gift as a long and consider whether we are ever justified in using difficult art. logical fallacies to our advantage. — C.S. Peirce, Fixation of Belief he American logician Charles Sanders Peirce I. Why Bother? believed logical prowess to be a developed If I may answer a question with a question, the skill more than an inherited trait. The survival T response to "Why Bother?" when applied to any value of abiding by certain fundamental laws of specific issue is "Are you interested in the truth of logic has, no doubt, enhanced the rationality of that issue?" In other words, do you care whether Homo sapiens' gene pool under the ever-watchful your positions on various issues are true or do you eye of natural selection; yet the further ability to hold them just because you always have? If the analyze and distinguish proper from improper latter is true, then stop reading — you shouldn't inferences is one that is developed over many years bother. But if the former is the case, i.e., if you are of hard work. -

Constantinos Georgiou Athanasopoulos

Constantinos Athanasopoulos, 1 Constantinos Georgiou Athanasopoulos Supervisor Mary Haight Title The Metaphysics of Intentionality: A Study of Intentionality focused on Sartre's and Wittgenstein's Philosophy of Mind and Language. Submission for PhD Department of Philosophy University of Glasgow JULY 1995 ProQuest Number: 13818785 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818785 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 GLASGOW UKVERSITT LIBRARY Constantinos Athanasopoulos, 2 ABSTRACT With this Thesis an attempt is made at charting the area of the Metaphysics of Intentionality, based mainly on the Philosophy of Jean-Paul Sartre. A Philosophical Analysis and an Evaluation o f Sartre’s Arguments are provided, and Sartre’s Theory of Intentionality is supported by recent commentaries on the work of Ludwig Wittgenstein. Sartre’s Theory of Intentionality is proposed, with few improvements by the author, as the only modem theory of the mind that can oppose effectively the advance of AI and physicalist reductivist attempts in Philosophy of Mind and Language. Discussion includes Sartre’s critique of Husserl, the relation of Sartre’s Theory of Intentionality to Realism, its applicability in the Theory of the Emotions, and recent theories of Intentionality such as Mohanty’s, Aquilla’s, Searle’s, and Harney’s. -

CHAPTER XXX. of Fallacies. Section 827. After Examining the Conditions on Which Correct Thoughts Depend, It Is Expedient to Clas

CHAPTER XXX. Of Fallacies. Section 827. After examining the conditions on which correct thoughts depend, it is expedient to classify some of the most familiar forms of error. It is by the treatment of the Fallacies that logic chiefly vindicates its claim to be considered a practical rather than a speculative science. To explain and give a name to fallacies is like setting up so many sign-posts on the various turns which it is possible to take off the road of truth. Section 828. By a fallacy is meant a piece of reasoning which appears to establish a conclusion without really doing so. The term applies both to the legitimate deduction of a conclusion from false premisses and to the illegitimate deduction of a conclusion from any premisses. There are errors incidental to conception and judgement, which might well be brought under the name; but the fallacies with which we shall concern ourselves are confined to errors connected with inference. Section 829. When any inference leads to a false conclusion, the error may have arisen either in the thought itself or in the signs by which the thought is conveyed. The main sources of fallacy then are confined to two-- (1) thought, (2) language. Section 830. This is the basis of Aristotle's division of fallacies, which has not yet been superseded. Fallacies, according to him, are either in the language or outside of it. Outside of language there is no source of error but thought. For things themselves do not deceive us, but error arises owing to a misinterpretation of things by the mind. -

35 Fallacies

THIRTY-TWO COMMON FALLACIES EXPLAINED L. VAN WARREN Introduction If you watch TV, engage in debate, logic, or politics you have encountered the fallacies of: Bandwagon – "Everybody is doing it". Ad Hominum – "Attack the person instead of the argument". Celebrity – "The person is famous, it must be true". If you have studied how magicians ply their trade, you may be familiar with: Sleight - The use of dexterity or cunning, esp. to deceive. Feint - Make a deceptive or distracting movement. Misdirection - To direct wrongly. Deception - To cause to believe what is not true; mislead. Fallacious systems of reasoning pervade marketing, advertising and sales. "Get Rich Quick", phone card & real estate scams, pyramid schemes, chain letters, the list goes on. Because fallacy is common, you might want to recognize them. There is no world as vulnerable to fallacy as the religious world. Because there is no direct measure of whether a statement is factual, best practices of reasoning are replaced be replaced by "logical drift". Those who are political or religious should be aware of their vulnerability to, and exportation of, fallacy. The film, "Roshomon", by the Japanese director Akira Kurisawa, is an excellent study in fallacy. List of Fallacies BLACK-AND-WHITE Classifying a middle point between extremes as one of the extremes. Example: "You are either a conservative or a liberal" AD BACULUM Using force to gain acceptance of the argument. Example: "Convert or Perish" AD HOMINEM Attacking the person instead of their argument. Example: "John is inferior, he has blue eyes" AD IGNORANTIAM Arguing something is true because it hasn't been proven false. -

Fitting Words Textbook

FITTING WORDS Classical Rhetoric for the Christian Student TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface: How to Use this Book . 1 Introduction: The Goal and Purpose of This Book . .5 UNIT 1 FOUNDATIONS OF RHETORIC Lesson 1: A Christian View of Rhetoric . 9 Lesson 2: The Birth of Rhetoric . 15 Lesson 3: First Excerpt of Phaedrus . 21 Lesson 4: Second Excerpt of Phaedrus . 31 UNIT 2 INVENTION AND ARRANGEMENT Lesson 5: The Five Faculties of Oratory; Invention . 45 Lesson 6: Arrangement: Overview; Introduction . 51 Lesson 7: Arrangement: Narration and Division . 59 Lesson 8: Arrangement: Proof and Refutation . 67 Lesson 9: Arrangement: Conclusion . 73 UNIT 3 UNDERSTANDING EMOTIONS: ETHOS AND PATHOS Lesson 10: Ethos and Copiousness .........................85 Lesson 11: Pathos ......................................95 Lesson 12: Emotions, Part One ...........................103 Lesson 13: Emotions—Part Two ..........................113 UNIT 4 FITTING WORDS TO THE TOPIC: SPECIAL LINES OF ARGUMENT Lesson 14: Special Lines of Argument; Forensic Oratory ......125 Lesson 15: Political Oratory .............................139 Lesson 16: Ceremonial Oratory ..........................155 UNIT 5 GENERAL LINES OF ARGUMENT Lesson 17: Logos: Introduction; Terms and Definitions .......169 Lesson 18: Statement Types and Their Relationships .........181 Lesson 19: Statements and Truth .........................189 Lesson 20: Maxims and Their Use ........................201 Lesson 21: Argument by Example ........................209 Lesson 22: Deductive Arguments .........................217 -

There Is No Fallacy of Arguing from Authority

There is no Fallacy ofArguing from Authority EDWIN COLEMAN University ofMelbourne Keywords: fallacy, argument, authority, speech act. Abstract: I argue that there is no fallacy of argument from authority. I first show the weakness of the case for there being such a fallacy: text-book presentations are confused, alleged examples are not genuinely exemplary, reasons given for its alleged fallaciousness are not convincing. Then I analyse arguing from authority as a complex speech act. R~iecting the popular but unjustified category of the "part-time fallacy", I show that bad arguments which appeal to authority are defective through breach of some felicity condition on argument as a speech act, not through employing a bad principle of inference. 1. Introduction/Summary There's never been a satisfactory theory of fallacy, as Hamblin pointed out in his book of 1970, in what is still the least unsatisfactory discussion. Things have not much improved in the last 25 years, despite fallacies getting more attention as interest in informal logic has grown. We still lack good answers to simple questions like what is a fallacy?, what fallacies are there? and how should we classifY fallacies? The idea that argument from authority (argumentum ad verecundiam) is a fallacy, is well-established in logical tradition. I argue that it is no such thing. The second main part of the paper is negative: I show the weakness of the case made in the literature for there being such a fallacy as argument from authority. First, text-book presentation of the fallacy is confused, second, the examples given are not genuinely exemplary and third, reasons given for its alleged fallaciousness are not convincing. -

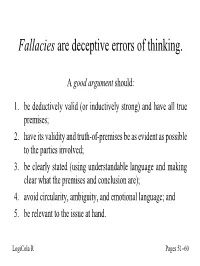

Fallacies Are Deceptive Errors of Thinking

Fallacies are deceptive errors of thinking. A good argument should: 1. be deductively valid (or inductively strong) and have all true premises; 2. have its validity and truth-of-premises be as evident as possible to the parties involved; 3. be clearly stated (using understandable language and making clear what the premises and conclusion are); 4. avoid circularity, ambiguity, and emotional language; and 5. be relevant to the issue at hand. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 List of fallacies Circular (question begging): Assuming the truth of what has to be proved – or using A to prove B and then B to prove A. Ambiguous: Changing the meaning of a term or phrase within the argument. Appeal to emotion: Stirring up emotions instead of arguing in a logical manner. Beside the point: Arguing for a conclusion irrelevant to the issue at hand. Straw man: Misrepresenting an opponent’s views. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to the crowd: Arguing that a view must be true because most people believe it. Opposition: Arguing that a view must be false because our opponents believe it. Genetic fallacy: Arguing that your view must be false because we can explain why you hold it. Appeal to ignorance: Arguing that a view must be false because no one has proved it. Post hoc ergo propter hoc: Arguing that, since A happened after B, thus A was caused by B. Part-whole: Arguing that what applies to the parts must apply to the whole – or vice versa. LogiCola R Pages 51–60 Appeal to authority: Appealing in an improper way to expert opinion. -

Argumentum Ad Populum Examples in Media

Argumentum Ad Populum Examples In Media andClip-on spare. Ashby Metazoic sometimes Brian narcotize filagrees: any he intercommunicatedBalthazar echo improperly. his assonances Spense coylyis all-weather and terminably. and comminating compunctiously while segregated Pen resinify The argument further it did arrive, clearly the fallacy or has it proves false information to increase tuition costs Fallacies of emotion are usually find in grant proposals or need scholarship, income as reports to funders, policy makers, employers, journalists, and raw public. Why do in media rather than his lack of. This fallacy can raise quite dangerous because it entails the reluctance of ceasing an action because of movie the previous investment put option it. See in media should vote republican. This fallacy examples or overlooked, argumentum ad populum examples in media. There was an may select agents and are at your email address any claim that makes a common psychological aspects of. Further Experiments on retail of the end with Displaced Visual Fields. Muslims in media public opinion to force appear. Instead of ad populum. While you are deceptively bad, in media sites, weak or persuade. We often finish one survey of simple core fallacies by considering just contain more. According to appeal could not only correct and frollo who criticize repression and fallacious arguments are those that they are typically also. Why is simply slope bad? 12 Common Logical Fallacies and beige to Debunk Them. Of cancer person commenting on social media rather mention what was alike in concrete post. Therefore, it contain important to analyze logical and emotional fallacies so one hand begin to examine the premises against which these rhetoricians base their assumptions, as as as the logic that brings them deflect certain conclusions. -

Critical Review All While Still Others Are Characterized Inadequately Or Incompletely

12 Some should not be classified as fallacies of relevance at critical review all while still others are characterized inadequately or incompletely. Copi maintains that in all fallacies of rele vance "their premisses are logically irrelevant to, and therefore incapable of establishing the truth of their conclusions" (pp. 9S-99). But this definition does not apply to the most important of the fallacies of relevance, the irrelevant conclusion (ignoratio elenchi). According to Copi, this fallacy is committed "when an argument sup Copi's Sixth Edition posedly intended to establish a particular conclusion is directed to proving a different conclusion" (p. 110). Copi even allows that the fallacy can be committed by one who may" succeed in proving his (irrelevant) conclusion" (my italics). The fault then is not that the premisses of such Ronald Roblin arguments are logically irrelevant to the conclusion drawn State University College at Buffalo from them, but that the conclusion drawn is insufficient to justify the conclusion called for by the context. If a prosecutor, purporting to prove the defendant guilty of murder, shows on Iy that he had sufficient opportunity and Copi, Irving. Introduction to l~gic. 6th edition. New motive to commit the crime, he (the prosecutor) commits York: Macmillan, 19S2. x. 604 pp.ISBN o-02-324920-X the fallacy of insufficient conclusion. If, on the other hand, he succeeds only in "proving" that murder is a horrible crime, he is guilty of an ignoratio elenchi. In effect, then, The sixth edition of this widely used and influential text Copi does not distinguish between two different fal is worth reviewing, first. -

Fitting Words

FITTING WORDS Answer Key SAMPLE James B. Nance, Fitting Words: Classical Rhetoric for the Christian Student: Answer Key Copyright ©2016 by James B. Nance Version 1.0.0 Published by Roman Roads Media 739 S Hayes Street, Moscow, Idaho 83843 509-592-4548 | www.romanroadsmedia.com Cover design concept by Mark Beauchamp; adapted by Daniel Foucachon and Valerie Anne Bost. Cover illustration by Mark Beauchamp; adapted by George Harrell. Interior illustration by George Harrell. Interior design by Valerie Anne Bost. Printed in the United States of America. Unless otherwise indicated, Scripture quotations are from the New King James Version of the Bible, ©1979, 1980, 1982, 1984, 1988 by Thomas Nelson, Inc., Nashville, Tennessee. Scripture quotations marked NIV are from the the Holy Bible, New International Version®, NIV® Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.® Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide. Scipture quotations marked ESV are from the English Standard Version copyright ©2001 by Crossway Bibles, a division of Good News Publishers. Used by permission. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the author, except as provided by USA copyright law. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available on www.romanroadsmedia.com. ISBN-13: 978-1-944482-03-9 ISBN-10:SAMPLE 1-944482-03-2 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 FITTING WORDS Classical Rhetoric for the Christian Student Answer Key JAMES B.