Perceptions of Traditional Beauty Standards in Televised Pageants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2014 HUSKER FOOTBALL Game 4: Nebraska Vs. Miami

2014 HUSKER FOOTBALL Nebraska Media Relations 4 One Memorial Stadium 4 Lincoln, NE 68588-0123 4 Phone: (402) 472-2263 4 [email protected] 2014 Nebraska Schedule Date Opponent (TV) Time/Result Game 4: Aug. 30 Florida Atlantic (BTN) W, 55-7 Sept. 6 McNeese State (ESPNU) W, 31-24 Nebraska vs. Miami Sept. 13 at Fresno State (CBS Sports Net.) W, 55-19 Sept. 20, 2014 | Memorial Stadium Sept. 20 Miami (ESPN2) 7 p.m. Sept. 27 Illinois (HC) (BTN) 8 p.m. Lincoln, Neb. | 7 p.m. (CT) Oct. 4 at Michigan State (ABC/ESPN/2) 7 p.m. Huskers Hurricanes Oct. 18 at Northwestern (BTN) 6:30 p.m. Record: 3-0, 0-0 Game Information Record: 2-1, 0-1 Oct. 25 Rutgers TBA Rankings: AP–24; Television: ESPN2 Rankings: not ranked Nov. 1 Purdue TBA Coaches–22 Radio: Husker Sports Network Last Game: Nov. 15 at Wisconsin TBA Last Game: Capacity: 87,000 def. Arkansas St., 41-20 Nov. 22 Minnesota TBA def. Fresno St., 55-19 Surface: FieldTurf Coach: Al Golden Series Record: Tied, 5-5 Nov. 28 at Iowa TBA Coach: Bo Pelini UM/Career Record: Last Meeting:Miami 37, Nebraska 14, 2002 Rose Bowl All times Central Career/NU Record: 24-16, 4th year/ Special Events: 1994 National Championship Team 61-24, 7th year 51-50, 9th year Recognition, Brook Berringer Scholarship Presentation Television vs. Miami: 0-0 vs. Nebraska: 0-0 ESPN2 Joe Tessitore, Play-by-Play The Matchup Brock Huard, Analyst Two of college football’s most dominant programs meet for the first time in more than a decade on Saturday Shannon Spake, Sidelines when Nebraska plays host to the Miami Hurricanes at Memorial Stadium. -

Missouri Department of Corrections Reply Brief in SC98252

Electronically Filed - SUPREME COURT OF MISSOURI April 15, 2020 04:34 PM SC98252 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF MISSOURI THOMAS HOOTSELLE, JR., et al., Respondents, v. MISSOURI DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS, Appellant. Appeal from the Circuit Court of Cole County, Missouri The Honorable Patricia S. Joyce SUBSTITUTE REPLY BRIEF ERIC S. SCHMITT Attorney General D. John Sauer, Mo. Bar No. 58721 Solicitor General Julie Marie Blake, Mo. Bar No. 69643 Mary L. Reitz, Mo. Bar No. 37372 Missouri Attorney General’s Office P.O. Box 899 Jefferson City, Missouri 65102 Phone: 573-751-8870 [email protected] Attorneys for Appellant Electronically Filed - SUPREME COURT OF MISSOURI April 15, 2020 04:34 PM TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................................... 2 TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ..................................................................................... 4 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 9 ARGUMENT ...........................................................................................................10 I. Plaintiffs’ Pre-Shift and Post-Shift Activities Are Not Compensable (Supports Appellant’s Points I and II). .............................................................................10 A. The activities are not “integral and indispensable,” and are de miminis. 10 B. Responding to occasional emergencies does not transform pre-shift and post-shift time into compensable time................................................. -

Ladino and Indigenous Pageantry in Neocolonial Guatemala

THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER: LADINO AND INDIGENOUS PAGEANTRY IN NEOCOLONIAL GUATEMALA by Jillian L. Kite A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL August 2014 Copyright by Jillian L. Kite 2014 ii iii ABSTRACT Author: Jillian L. Kite Title: The Eye of the Beholder: Ladino and Indigenous Pageantry in Neocolonial Guatemala Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Co-Advisors: Dr. Josephine Beoku-Betts and Dr. Mark Harvey Degree: Master of Arts Year: 2014 In this thesis I utilize a feminist case study method to explore gender, race, authenticity, and nationalism in the context of globalization. Each year, Guatemala conducts two ethno-racially distinct pageants – one indigenous, the other ladina. The indigenous pageant prides itself on the authentic display of indigenous culture and physiognomies. On the contrary, during the westernized ladina pageant, contestants strive to adhere to western beauty ideals beauty and cultural norms engendered by discourses of whiteness. However, when the winner advances to the Miss World Pageant, they misappropriate elements of Mayan culture to express an authentic national identity in a way that is digestible to an international audience. In the study that follows, I examine the ways in which national and international pageants are reflective of their iv respective levels of social and political conflict and how they serve as mechanisms of manipulation by the elite at the national and global levels. v THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER: LADINO AND INDIGENOUS PAGEANTRY IN NEOCOLONIAL GUATEMALA I. -

Miss South Carolina Teen Usa, K. Lee Graham Crowned Miss Teen Usa 2014 at Atlantis, Paradise Island Resort in the Bahamas

MISS SOUTH CAROLINA TEEN USA, K. LEE GRAHAM CROWNED MISS TEEN USA 2014 AT ATLANTIS, PARADISE ISLAND RESORT IN THE BAHAMAS New York, NY – August 4, 2014 – 17 year old K. Lee Graham of Chapin, South Carolina was crowned Miss Teen USA 2014 this past Saturday at the beautiful Atlantis, Paradise Island resort in The Bahamas on August 2, 2014. The 2014 MISS TEEN USA® Competition streamed live at www.missteenusa.com. K. Lee (“Kaylee”) is a high school senior and honor student, ranking first in her class at Chapin High School, a highly competitive school that provides challenging curricula for their students. When she is not studying, K. Lee is very involved in theater and has even been her high school’s mascot, an Eagle. Competing in pageants runs in her family as K. Lee’s mother, Jennifer, held the Miss South Carolina Teen USA title in 1985. K. Lee is the second oldest of five children and is an active blogger encouraging girls to find true beauty by embracing themselves, others, and their communities. Hosting this year’s pageant was Miss USA 2013 Erin Brady and Australian television host Karl Schmid. The presentation show, which took place Friday, August 1st, was hosted by Cassidy Wolf, Miss Teen USA 2013 and Nick Teplitz, television writer and comedian. This year’s distinguished panel of judges included: Fred Nelson, President/Executive Producer of People’s Choice Awards; Mallory Tucker, Theatrical Department talent agent at CESD Talent Agency; Amber Katz, founder of award-winning, pop culture-infused beauty blog rouge18.com; Chriselle Lim, influential fashion blogger, spokesperson for Estee Lauder digital; Joseph Parisi, Vice President for Enrollment Management at Lindenwood University, which provides scholarships for all 51 Miss Teen USA contestants. -

Scholarship Resources for Minority Students

Welcome to Scholarship Resources for Diverse Populations! Compiled by Valerie Garr, [email protected] The University of Iowa, College of Nursing Diversity Office (Updated 7/31/13 VSG) IMPORTANT: This is an evolving list of potential scholarship resources for students who are one of or in combination of the following: minority, underrepresented, first generation, female, or undocumented, This list includes scholarship and financial aid resource information from sources predominantly not connected to the University of Iowa. Thus, unless noted, the University of Iowa does not determine award criteria, dollar amounts, application procedures, deadlines, or future renewal. This scholarship information may be helpful in assisting prospective and current students with their pursuit to finance a college education. The websites listed have been checked for authenticity but the UI is not responsible for the content, updating of, or access to any of these websites unless they are official UI links. It is recommended that you use this listing and the other information provided as a supplement to filing the FAFSA. Tips for Getting Scholarships and Other Financial Aid: • Work hard to get and maintain good grades in school • Perform as well as you can on your ACT, SAT, GRE etc… • Start early looking for scholarship money: internet, library, your community etc... • If a scholarship requires a letter of recommendation, ask your teacher/professor or counselor/advisor; someone who knows your academic ability in the classroom • If a scholarship requires you to write an essay, have a teacher/professor or counselor /advisor read your essay before you submit a final version; be prepared to re-write before final submission • Read the scholarship forms, applications, and deadlines carefully and follow instructions as indicated—Look for scholarships a YEAR In ADVANCE of your need! • File your FAFSA electronically as soon as possible after January 1st. -

021215Front FREE PRESS FRONT.Qxd

How to Voices of the Does Race Ancestors: Handle Quotes from Play a Role Great African a Mean Americans Leaders Child in Tipping? that are Still Page 2 Relevant Today Page 7 Page 4 Win $100 PRST STD 50c U.S. Postage PAID Jacksonville, FL in Our Permit No. 662 “Firsts” RETURN SERVICE REQUESTED History Contest Page 13 50 Cents Dartmouth College Introduces Volume 28 No. 14 Jacksonville, Florida February 12-17, 2015 #BlackLivesMatter Course Police Killings Underscore #BlackLivesMatter is what many bill as the name of the current move- ment toward equal rights. The hashtag, which drove information about protests happening in cities around the world, was started by Opal the Need for Reform Tometi, Patrisse Cullors and Alicia Garza in 2012, in response to the By Freddie Allen fatally shooting Brown. killing of Trayvon Martin. NNPA Correspondent Targeting low-level lawbreakers Now the movement has found its way into academic spaces. Blacks and Latinos are incarcer- epitomizes “broken windows” pop- Dartmouth College is introducing the #BlackLivesMatter course on its ated at disproportionately higher ularized during William Bratton’s campus this spring semester that will take a look at present-day race, rates in part because police target first tenure as commissioner of the structural inequality and violence issues, and examine the topics in a them for minor crimes, according a New York Police Department under historical context. report titled, “Black Lives Matter: then-Mayor Rudy Giuliani. Mayor “10 Weeks, 10 Professors: #BlackLivesMatter” will feature lectures Eliminating Racial Inequity in the Bill de Blasio reappointed Bratton from about 15 professors at Dartmouth College across disciplines, Criminal Justice System” by the to that position and he remains including anthropology, history, women's and gender studies, English Sentencing Project, a national, non- “committed to this style of order- and others. -

190 North Avenue

cover 11/3/03 2:37 PM Page 1 Winter 2003 Homecoming2003 preview 11/4/03 10:42 AM Page 3 3 Tech Topics Tech Vol. 40, No. 2 Winter 2003 gtalumni.org • Winter 2003 A Quick Read of Winter 2003 Contents Publisher: Joseph P. Irwin IM 80 Editor: John C. Dunn Associate Editor: Neil B. McGahee 08 True Grit 23 To the Point Assistant Editor: Maria M. Lameiras Assistant Editor: Kimberly Link-Wills Junior’s moved to smaller digs. Its next building was Herky Harris’ “giddyap” business style spurred his Design: Andrew Niesen & Rachel LaCour Niesen leveled by a wrecking ball. Through it all, this Tech career to the top and has proven invaluable to the institution has survived to “hold the dust.” Georgia Tech Foundation. Alumni Association Executive Committee 09 Planet of the Ape 25 Saving Lives, Saving Jobs L. Thomas Gay IM 66, president Robert L. Hall IM 64, past president Terry Maple, head of Georgia Alumnus David Rice’s manufac- Carey H. Brown IE 69, president elect/treasurer Tech’s new Center for turing business took a direct hit J. William Goodhew III IM 61, vice president activities Conservation and Behavior when a luggage company Janice N. Wittschiebe Arch 78, MS Arch 80, and former director of Zoo packed its bags and moved over- vice president Roll Call Atlanta, kicked off the seas. Not only did Rice’s compa- C. Meade Sutterfield EE 72, vice president communications Joseph P. Irwin IM 80, vice president and executive director Alumni Association’s ny survive the wound, it’s Homecoming events by shar- thriving as a maker of ing what he learned from bulletproof vests. -

BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Latar Belakang Popularitas Kontes

BAB I PENDAHULUAN 1.1 Latar Belakang Popularitas kontes kecantikan yang diawali di Eropa telah merambah ke banyak negara termasuk Indonesia. Sejumlah kontes kecantikan meramaikan industri pertelevisian, salah satunya adalah kontes kecantikan Puteri Indonesia yang sudah diselenggarakan sejak tahun 1992. Ajang Puteri Indonesia digagas oleh pendiri PT Mustika Ratu, yaitu Mooryati Soedibyo. Di tahun 2020, kompetisi Puteri Indonesia kembali digelar dan ditayangkan di stasiun televisi SCTV. Penyelenggaraan kontes, melibatkan 39 finalis yang berlomba menampilkan performa terbaik untuk memperebutkan gelar dan mahkota Puteri Indonesia. Pemilihan 39 finalis yang berkompetisi di panggung Puteri Indonesia melalui proses yang tidak mudah. Yayasan Puteri Indonesia (YPI) menjelaskan bahwa perempuan yang berhasil menjadi perwakilan provinsi dipilih melalui seleksi ketat. YPI membebankan syarat utama bagi calon peserta untuk memenuhi kriteria “Brain, Beauty, Behavior”. Secara spesifik YPI mematok kontestan harus memiliki tinggi minimal 170 cm, berpenampilan menarik, dan pernah atau sedang menempuh pendidikan di perguruan tinggi. Nantinya, apabila berhasil terpilih sebagai pemenang, maka 3 besar Puteri Indonesia akan mengikuti ajang kecantikan internasional yaitu, 1 2 Miss Universe, Miss International, dan Miss Supranational (www.puteri- indonesia.com, 2019). Konstruksi ideal “Brain, Beauty, Behavior” atau 3B telah melekat dengan kontes Puteri Indonesia, dan menjadi harapan bagi masyarakat untuk melihat figur perempuan ideal. Namun, penyelenggaraan kontes di tahun 2020 mendapat sorotan terkait dengan performa finalis saat malam final. Salah satu finalis yang menjadi perbincangan hangat adalah Kalista Iskandar, perwakilan dari Provinsi Sumatera Barat. Langkahnya terhenti di babak 6 besar setelah gagal menjawab pertanyaan terkait Pancasila. Kegagalannya dalam sesi tanya-jawab, menghiasi pemberitaan media massa hingga menjadi topik yang paling banyak dibicarakan (trending topic) di media sosial Twitter. -

Extensions of Remarks E 1521 EXTENSIONS of REMARKS

July 27, 1995 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD Ð Extensions of Remarks E 1521 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS KEEP THE GREAT LAKES ENVI- and Prime Minister Ciller for taking an impor- VISIT OF PRESIDENT KIM TO THE RONMENTAL RESEARCH LAB tant step towards strengthening democracy. UNITED STATES OPEN On Sunday, July 23, Turkey's Parliament ap- proved 16 constitutional amendments which HON. GARY L. ACKERMAN HON. DAVID E. BONIOR are part of a democratization plan introduced OF NEW YORK OF MICHIGAN last year. The Parliament also agreed to re- IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES sume work in September on amending article IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Wednesday, July 26, 1995 Wednesday, July 26, 1995 8 of the Anti-Terror Law, which is widely used to criminalize anti-government and pro-Kurdish Mr. ACKERMAN. Mr. Speaker, I rise today Mr. BONIOR. Mr. Speaker, this House has expressions. These reforms are considered to welcome a very distinguished statesman long recognized that the work of NOAA bene- prerequisites to Turkey's acceptance into a and friend of the United States, President Kim fits all Americans. European Union customs agreement this fall. Yong-sam of the Republic of Korea. NOAA's research on weather, atmosphere, Mr. Speaker, I am very encouraged by the fact Since his ascension to the presidency in oceans, and space continues to help us un- that the amendments were adopted by a vote 1993, President Kim has worked tirelessly to derstand the environment which we all depend of 360±32 after weeks of tumultuous debate. promote democracy and economic liberaliza- upon for survivalÐand has shown us ways to tion in Korea. -

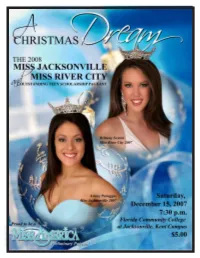

2008 Miss Jax and RC Program Final Program Bookversion

Our Mistresses of Ceremonies As an entertainer and actor, Michelle Miller has been performing for over 20 years. Her music highlights include Michelle Miller performances with the Jacksonville Jaguars, American Music Jubilee Theater, PBR Tour, Concert on the Green, Orlando Magic and USO events. She performed and co- produced the USO 65th Anniversary Celebration, which starred Ed McMahon, and Mickey & Jan Rooney. Michelle enjoys staying busy filming commercials, corporate films, recording voiceovers, and serving as professional host/emcee. Highlights include Griffin Lincoln Mercury, Stewart Lighting One, Kossak Companies, American Home Builders, Annie OAKley’s, Sunbelt National Music Video, WJXT Auctioneer & HBO movie “Recount”. Being no stranger to the pageant community, she has served as Jacksonville Miss TEEN, Florida Miss TEEN, National Top Ten Finalist, Miss Florida Community College at Jacksonville, and Florida Azalea Queen. Proudly calling Jacksonville home, Michelle is represented by First Coast Talent Agency. Candace O’Steen Candace Osteen is a Starke native and has been involved with pageantry for 10 years. She has been involved in every aspect of pageantry from competing to coaching and even producing. She was a part of the Miss Florida Organization for 4 years and competed with the titles Miss Mandarin, Miss Ocala Marion County, Miss St. Augustine and Miss Jacksonville. She is a graduate of Florida Community College at Jacksonville and is currently finishing her Bachelor degree at the University of North Florida. Candace is -

Journeys 2008 Web.Indd

Journeys An Anthology of Adult Student Writings Freed Spirit Donald Egge, Duluth Journeys 2008 An Anthology of Adult Student Writings Journeys is a project of the Minnesota Literacy Council, a nonprofi t organization dedicated to improving literacy statewide. Our mission is to share the power of learning through education, community building and advocacy. Special thanks to our editors: Elissa Cottle, Katie McMillen and Christopher Pommier, and to Minnesota Literacy Council staff members Guy Haglund, Jane Cagle-Kemp, Cathy Grady and Allison Runchey for their work on this year’s Journeys. Th is is our 19th year of publishing writing by adults enrolled in reading, English as a Second Language, GED, and other adult basic education classes in Minnesota. Please also see Journeys online at www.theMLC.org/Journeys. Submit writing for Journeys by contacting www.theMLC.org, 651-645-2277 or 800-225-READ. Join the journey of the Minnesota Literacy Council by: - Referring adults in need of literacy assistance to the Adult Literacy Hotline at 800-222-1990 or www.theMLC.org/hotline. - Tutoring adults in reading, ESL, citizenship or GED. Contact [email protected]. - Distributing fl iers and emails or hosting events. Call 651-645-2277 for materials. - Making tax deductible contributions. Send donations to the Minnesota Literacy Council, 756 Transfer Road, St. Paul, MN 55114. For other giving options, contact 651-645-2277, 800-225-READ or www.theMLC.org/donate. TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 i remember 19 america the foreign 27 it’s so different from home 37 my successes -

Sink Or Swim: Deciding the Fate of the Miss America Swimsuit Competition

Volume 4, Issue No. 1. Sink or Swim: Deciding the Fate of the Miss America Swimsuit Competition Grace Slapak Tulane University, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA ÒÏ Abstract: The Miss America beauty pageant has faced widespread criticism for the swimsuit portion of its show. Feminists claim that the event promotes objectification and oversexualization of contestants in direct contrast to the Miss America Organization’s (MAO) message of progressive female empowerment. The MAO’s position as the leading source of women’s scholarships worldwide begs the question: should women have to compete in a bikini to pay for a place in a cellular biology lecture? As dissent for the pageant mounts, the new head of the MAO Board of Directors, Gretchen Carlson, and the first all-female Board of Directors must decide where to steer the faltering organization. The MAO, like many other businesses, must choose whether to modernize in-line with social movements or whole-heartedly maintain their contentious traditions. When considering the MAO’s long and controversial history, along with their recent scandals, the #MeToo Movement, and the complex world of television entertainment, the path ahead is anything but clear. Ultimately, Gretchen Carlson and the Board of Directors may have to decide between their feminist beliefs and their professional business aspirations. Underlying this case, then, is the question of whether a sufficient definition of women’s leadership is simply leadership by women or if the term and its weight necessitate leadership for women. Will the board’s final decision keep this American institution afloat? And, more importantly, what precedent will it set for women executives who face similar quandaries of identity? In Murky Waters The Miss America Pageant has long occupied a special place in the American psyche.