Performances of Dyke Identifications Through Social Networking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in the Commonwealth

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth: Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites © Human Rights Consortium, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978-1-912250-13-4 (2018 PDF edition) DOI 10.14296/518.9781912250134 Institute of Commonwealth Studies School of Advanced Study University of London Senate House Malet Street London WC1E 7HU Cover image: Activists at Pride in Entebbe, Uganda, August 2012. Photo © D. David Robinson 2013. Photo originally published in The Advocate (8 August 2012) with approval of Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG) and Freedom and Roam Uganda (FARUG). Approval renewed here from SMUG and FARUG, and PRIDE founder Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera. Published with direct informed consent of the main pictured activist. Contents Abbreviations vii Contributors xi 1 Human rights, sexual orientation and gender identity in the Commonwealth: from history and law to developing activism and transnational dialogues 1 Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites 2 -

" We Are Family?": the Struggle for Same-Sex Spousal Recognition In

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be fmrn any type of computer printer, The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reprodudion. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e-g., maps, drawings, &arb) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to tight in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6' x 9" black and Mite photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustratims appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell 8 Howell Information and Leaning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 "WE ARE FAMILY'?": THE STRUGGLE FOR SAME-SEX SPOUSAL RECOGNITION IN ONTARIO AND THE CONUNDRUM OF "FAMILY" lMichelIe Kelly Owen A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology and Equity Studies in Education Ontario Institute for Studies in Education of the University of Toronto Copyright by Michelle Kelly Owen 1999 National Library Bibliothiique nationale l*B of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographic Services sewices bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. -

Montréal's Gay Village

Produced By: Montréal’s Gay Village Welcoming and Increasing LGBT Visitors March, 2016 Welcoming LGBT Travelers 2016 ÉTUDE SUR LE VILLAGE GAI DE MONTRÉAL Partenariat entre la SDC du Village, la Ville de Montréal et le gouvernement du Québec › La Société de développement commercial du Village et ses fiers partenaires financiers, que sont la Ville de Montréal et le gouvernement du Québec, sont heureux de présenter cette étude réalisée par la firme Community Marketing & Insights. › Ce rapport présente les résultats d’un sondage réalisé auprès de la communauté LGBT du nord‐est des États‐ Unis (Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, État de New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, Pennsylvanie, New Jersey, Delaware, Maryland, Virginie, Ohio, Michigan, Illinois), du Canada (Ontario et Colombie‐Britannique) et de l’Europe francophone (France, Belgique, Suisse). Il dresse un portrait des intérêts des touristes LGBT et de leurs appréciations et perceptions du Village gai de Montréal. › La première section fait ressortir certaines constatations clés alors que la suite présente les données recueillies et offre une analyse plus en détail. Entre autres, l’appréciation des touristes qui ont visité Montréal et la perception de ceux qui n’en n’ont pas eu l’occasion. › L’objectif de ce sondage est de mieux outiller la SDC du Village dans ses démarches de promotion auprès des touristes LGBT. 2 Welcoming LGBT Travelers 2016 ABOUT CMI OVER 20 YEARS OF LGBT INSIGHTS › Community Marketing & Insights (CMI) has been conducting LGBT consumer research for over 20 years. Our practice includes online surveys, in‐depth interviews, intercepts, focus groups (on‐site and online), and advisory boards in North America and Europe. -

Curating Precarity. Swedish Queer Film Festivals As Micro-Activism

Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis Uppsala Studies in Media and Communication 16 Curating Precarity Swedish Queer Film Festivals as Micro-Activism SIDDHARTH CHADHA Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Lecture Hall 2, Ekonomikum, Kyrkogårdsgatan 10, Uppsala, Thursday, 15 April 2021 at 13:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Faculty examiner: Dr. Marijke de Valck (Department of Media and Culture, Utrecht University). Abstract Chadha, S. 2021. Curating Precarity. Swedish Queer Film Festivals as Micro-Activism. Uppsala Studies in Media and Communication 16. 189 pp. Uppsala: Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. ISBN 978-91-513-1145-6. This research is based on ethnographic fieldwork conducted at Malmö Queer Film Festival and Cinema Queer Film Festival in Stockholm, between 2017-2019. It explores the relevance of queer film festivals in the lives of LGBTQIA+ persons living in Sweden, and reveals that these festivals are not simply cultural events where films about gender and sexuality are screened, but places through which the political lives of LGBTQIA+ persons become intelligible. The queer film festivals perform highly contextualized and diverse sets of practices to shape the LGBTQIA+ discourse in their particular settings. This thesis focuses on salient features of this engagement: how the queer film festivals define and articulate “queer”, their engagement with space to curate “queerness”, the role of failure and contingency in shaping the queer film festivals as sites of democratic contestations, the performance of inclusivity in the queer film festival organization, and the significance of these events in the lives of the people who work or volunteer at these festivals. -

Cultivating the Daughters of Bilitis Lesbian Identity, 1955-1975

“WHAT A GORGEOUS DYKE!”: CULTIVATING THE DAUGHTERS OF BILITIS LESBIAN IDENTITY, 1955-1975 By Mary S. DePeder A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in History Middle Tennessee State University December 2018 Thesis Committee: Dr. Susan Myers-Shirk, Chair Dr. Kelly A. Kolar ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I began my master’s program rigidly opposed to writing a thesis. Who in their right mind would put themselves through such insanity, I often wondered when speaking with fellow graduate students pursuing such a goal. I realize now, that to commit to such a task, is to succumb to a wild obsession. After completing the paper assignment for my Historical Research and Writing class, I was in far too deep to ever turn back. In this section, I would like to extend my deepest thanks to the following individuals who followed me through this obsession and made sure I came out on the other side. First, I need to thank fellow history graduate student, Ricky Pugh, for his remarkable sleuthing skills in tracking down invaluable issues of The Ladder and Sisters. His assistance saved this project in more ways than I can list. Thank-you to my second reader, Dr. Kelly Kolar, whose sharp humor and unyielding encouragement assisted me not only through this thesis process, but throughout my entire graduate school experience. To Dr. Susan Myers- Shirk, who painstakingly wielded this project from its earliest stage as a paper for her Historical Research and Writing class to the final product it is now, I am eternally grateful. -

Butch-Femme by Teresa Theophano

Butch-Femme by Teresa Theophano Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2004, glbtq, inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com A butch-femme couple The concept of butch and femme identities have long been hotly debated within the participating in a group lesbian community, yet even achieving a consensus as to exactly what the terms wedding ceremony in "butch" and "femme" mean can be extraordinarily difficult. In recent years, these Taiwan. words have come to describe a wide spectrum of individuals and their relationships. It is easiest, then, to begin with an examination of butch-femme culture and meaning from a historical perspective. Butch and femme emerged in the early twentieth century as a set of sexual and emotional identities among lesbians. To give a general but oversimplified idea of what butch-femme entails, one might say that butches exhibit traditionally "masculine" traits while femmes embody "feminine" ones. Although oral histories have demonstrated that butch-femme couples were seen in America as far back as the turn of the twentieth century, and that they were particularly conspicuous in the 1930s, it is the mid-century working-class and bar culture that most clearly illustrate the archetypal butch-femme dynamic. Arguably, during the period of the 1940s through the early 1960s, butches and femmes were easiest to recognize and characterize: butches with their men's clothing, DA haircuts, and suave manners often found their more traditionally styled femme counterparts, wearing dresses, high heels, and makeup, in the gay bars. A highly visible and accepted way of living within the lesbian community, butch-femme was in fact considered the norm among lesbians during the 1950s. -

17. Dyke, Dyke, Dyke!

JENNIFER TURLEY 17. DYKE, DYKE, DYKE! How does it feel to have a child who is gay? I’ve been asked that several times. Believe me, I’d rather face that question than have that ugly, accusing glare from some small-minded person who is allowing themselves to believe that I “allowed my child to choose to be gay.” How can a person best describe the cross between trying to be a responsible and well-behaved adult, and wanting to choke the very last breath out of some ignoramus who stands within earshot saying despicable and hateful things about the child who you love more than your own life? By now, many people have either read or heard about the poem by Emily Perl Kingsley entitled, “Welcome to Holland.” The poem depicts the way a mother feels upon learning that her newborn child is disabled, after preparing herself for a “typical” child during her pregnancy. I believe that all mothers have certain expectations during pregnancy, and then we solidify certain expectations upon learning the sex of the baby. I suppose that could be my segue into what it’s like to have a daughter who is lesbian, yes? You hear the doctor pronounce to all in the room, “It’s a girl!” and you begin imagining her school dances and formals, and even a brief thought of her wedding, though it’s way down the road. You have certain expectations just because the child is born with a particular set of genitalia. It’s unfortunate that it all begins that way, but I know that it’s common, no matter how erroneous. -

REBELS on POINTE Featuring LES BALLETS TROCKADERO DE MONTE CARLO

REBELS ON POINTE Featuring LES BALLETS TROCKADERO DE MONTE CARLO A film by Bobbi Jo Hart An Icarus Films Release Produced by Adobe Productions International "Laugh out loud funny! Knocks the stuffy art off its pedestal and makes it an open, inclusive, and accessible experience. This spirited doc shows how much better art—and life—can be when everyone is invited to the party." —POV Magazine (718) 488-8900 www.IcarusFilms.com LOGLINE A riotous, irreverent all-male comic ballet troupe, Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo challenges gender and artistic norms in the conservative world of ballet. SYNOPSIS Exploring universal themes of identity, dreams and family, Rebels on Pointe celebrates the legendary dance troupe Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo. The notorious all- male drag ballet company, commonly known as “The Trocks,” was founded in 1974 in New York City on the heels of the Stonewall riots and has since developed a passionate cult following around the world. The film juxtaposes intimate behind-the-scenes access, rich archives and history, engaging character driven stories, and dance performances shot in North America, Europe and Japan. Rebels on Pointe is a creative blend of gender-bending artistic expression, diversity, passion and purpose which proves that a ballerina can be an act of revolution… in a tutu. Rebels on Pointe introduces dancers that director Bobbi Jo Hart filmed for four years: Bobby Carter from Charleston, South Carolina; Raffaele Morra from Fossano, Italy; Chase Johnsey from Lakeland, Florida; and Carlos Hopuy is from Havana, Cuba. With personal histories impacted by the AIDS crisis and eventual growth of the LGBT civil rights movement, the film’s main characters share powerful and inspiring anecdotes about growing up gay, their relationships with their families, and their challenges in becoming professional ballerinas. -

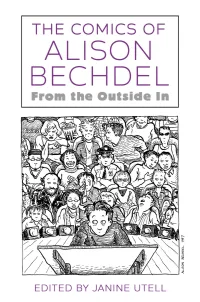

The Comics of Alison Bechdel from the Outside In

The Comics of Alison Bechdel From the Outside In Edited by Janine Utell University Press of Mississippi / Jackson CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS IX THE WORKS OF ALISON BECHDEL XI INTRODUCTION Serializing the Self in the Space between Life and Art JANINE UTELL XIII I. IN AND/OR OUT: QUEER THEORY, LESBIAN COMICS, AND THE MAINSTREAM THE HOSPITABLE AESTHETICS OF ALISON BECHDEL VANESSA LAUBER 3 “GIRLIE MAN, MANLY GIRL, IT’S ALL THE SAME TO ME” How Dykes to Watch Out For Shifted Gender and Comix ANNE N. THALHEIMER 22 DISSEMINATING QUEER THEORY Dykes to Watch Out For and the Transmission of Theoretical Thought KATHERINE PARKER-HAY 36 BECHDEL’S MEN AND MASCULINITY Gay Pedant and Lesbian Man JUDITH KEGAN GARDINER 52 VI CONTENTS MO VAN PELT Dykes to Watch Out For and Peanuts MICHELLE ANN ABATE 68 II. INTERIORS: FAMILY, SUBJECTIVITY, MEMORY DANCING WITH MEMORY IN FUN HOME ALISSA S. BOURBONNAIS 89 “IT BOTH IS AND ISN’T MY LIFE” Autobiography, Adaptation, and Emotion in Fun Home, the Musical LEAH ANDERST 105 GENERATIONAL TRAUMA AND THE CRISIS OF APRÈS-COUP IN ALISON BECHDEL’S GRAPHIC MEMOIRS NATALJA CHESTOPALOVA 119 THE EXPERIMENTAL INTERIORS OF ALISON BECHDEL’S ARE YOU MY MOTHER? YETTA HOWARD 135 INCHOATE KINSHIP Psychoanalytic Narrative and Queer Relationality in Are You My Mother? TYLER BRADWAY 148 III. PLACE, SPACE, AND COMMUNITY DECOLONIZING RURAL SPACE IN ALISON BECHDEL’S FUN HOME KATIE HOGAN 167 FUN HOME AND ARE YOU MY MOTHER? AS AUTOTOPOGRAPHY Queer Orientations and the Politics of Location KATHERINE KELP-STEBBINS 181 CONTENTS VII INSIDE THE ARCHIVES OF FUN HOME SUSAN R. -

For Love and for Justice: Narratives of Lesbian Activism

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2014 For Love and for Justice: Narratives of Lesbian Activism Kelly Anderson Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/8 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] For Love and For Justice: Narratives of Lesbian Activism By Kelly Anderson A dissertation submitted to the faculty of The Graduate Center, City University of New York in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History 2014 © 2014 KELLY ANDERSON All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Blanche Wiesen Cook Chair of Examining Committee Helena Rosenblatt Executive Officer Bonnie Anderson Bettina Aptheker Gerald Markowitz Barbara Welter Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract For Love and for Justice: Narratives of Lesbian Activism By Kelly Anderson Adviser: Professor Blanche Wiesen Cook This dissertation explores the role of lesbians in the U.S. second wave feminist movement, arguing that the history of women’s liberation is more diverse, more intersectional, -

Whipping Girl

Table of Contents Title Page Dedication Introduction Trans Woman Manifesto PART 1 - Trans/Gender Theory Chapter 1 - Coming to Terms with Transgen- derism and Transsexuality Chapter 2 - Skirt Chasers: Why the Media Depicts the Trans Revolution in ... Trans Woman Archetypes in the Media The Fascination with “Feminization” The Media’s Transgender Gap Feminist Depictions of Trans Women Chapter 3 - Before and After: Class and Body Transformations 3/803 Chapter 4 - Boygasms and Girlgasms: A Frank Discussion About Hormones and ... Chapter 5 - Blind Spots: On Subconscious Sex and Gender Entitlement Chapter 6 - Intrinsic Inclinations: Explaining Gender and Sexual Diversity Reconciling Intrinsic Inclinations with Social Constructs Chapter 7 - Pathological Science: Debunking Sexological and Sociological Models ... Oppositional Sexism and Sex Reassignment Traditional Sexism and Effemimania Critiquing the Critics Moving Beyond Cissexist Models of Transsexuality Chapter 8 - Dismantling Cissexual Privilege Gendering Cissexual Assumption Cissexual Gender Entitlement The Myth of Cissexual Birth Privilege Trans-Facsimilation and Ungendering 4/803 Moving Beyond “Bio Boys” and “Gen- etic Girls” Third-Gendering and Third-Sexing Passing-Centrism Taking One’s Gender for Granted Distinguishing Between Transphobia and Cissexual Privilege Trans-Exclusion Trans-Objectification Trans-Mystification Trans-Interrogation Trans-Erasure Changing Gender Perception, Not Performance Chapter 9 - Ungendering in Art and Academia Capitalizing on Transsexuality and Intersexuality -

Queer Tastes: an Exploration of Food and Sexuality in Southern Lesbian Literature Jacqueline Kristine Lawrence University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 5-2014 Queer Tastes: An Exploration of Food and Sexuality in Southern Lesbian Literature Jacqueline Kristine Lawrence University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Studies Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Lawrence, Jacqueline Kristine, "Queer Tastes: An Exploration of Food and Sexuality in Southern Lesbian Literature" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 1021. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/1021 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Queer Tastes: An Exploration of Food and Sexuality in Southern Lesbian Literature Queer Tastes: An Exploration of Food and Sexuality in Southern Lesbian Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in English By Jacqueline Kristine Lawrence University of Arkansas Bachelor of Arts in English, 2010 May 2014 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. _________________________ Dr. Lisa Hinrichsen Thesis Director _________________________ _________________________ Dr. Susan Marren Dr. Robert Cochran Committee Member Committee Member ABSTRACT Southern identities are undoubtedly influenced by the region’s foodways. However, the South tends to neglect and even to negate certain peoples and their identities. Women, especially lesbians, are often silenced within southern literature. Where Tennessee Williams and James Baldwin used literature to bridge gaps between gay men and the South, southern lesbian literature severely lacks a traceable history of such connections.