Mahabharata a STUDY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter Iv Data Analysis

CHAPTER IV DATA ANALYSIS Ramayana and Mahabharata are Wiracarita, the heroic stories which are well – known from one generation to another. These two great epics are originally written in Sanskrit. The author of Ramayana is Walmiki, and the author of Mahabharata is Bhagawan Wyasa. Ramayana and Mahabharata have been translated into various languages. In Indonesia, these two great epics have been retold in various versions such as Wayang kulit performance, dance, book, novel, and comic. For this research, the writer chooses the Mahabharata novel by Nyoman. S. Pendit. With the focus of the research on the heroic journey of Arjuna in this novel. In this chapter, the writer would like to answer and to analyze three problem formulations of this research. First, the writer would like to retell Arjuna‟s journey based on the twenty parts selected in the Mahabharata novel. After that, as the second problem formulation, the writer would like to compare to what extent the journey of Arjuna on the twenty parts selected in the Mahabharata novel fulfills the criteria of the Hero‟s Journey theory proposed by Joseph Campbell. The Hero‟s Journey theory itself consists of seventeen stages divided into three big stages: Departure – Initiation – Return. It can be seen from the journey of Arjuna in the Mahabharata novel by Nyoman. S. Pendit. After going through the several archetypal journey process framed in the Hero‟s Journey theory, Arjuna gets or shows the life virtues in himself. Therefore, as the third problem formulation, the 34 writer would like to mention what kind of life virtues showed by Arjuna on the twenty parts selected in the Mahabharata novel. -

The Civilization of India

'CORNIA, SAN DIEGO usaJH iliii DS 436 D97 HB In SUM^ Hill HI I A ——^— c SS33 1II1& A inos ^ (J REGIO 1 8 MAL 8 I ' 8Bi|LIBRARY 8 ===== 5 ^H •''"'''. F 1 ^^^? > jH / I•' / 6 3 mm^ LIBRARY "*'**••* OK SAN 0fO3O N F CAL,F0RNI in JmNiln 1 M, . * san 3 1822 00059 8219 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from Microsoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/civilizationofinOOdutt HE TEMPLE PRIMERS THE CIVILIZATION OF INDIA By ROMESH C. DUTT, CLE. A. : » "";. : ;-. ' 1 - fejlSP^^*^-:'H-' : .;.Jlffsil if? W?*^m^^lmSmJpBSS^S I^~lmi ~5%^M'J&iff*^^ ygjBfB^ THE GREAT TEMPLE OF BHUVANESWARA CIVILIZATIOn OF.IHDIA I900& 29 &30 BEDFORD-STREET* LQNDOM All rights reserved CONTENTS PAGE I. VEDIC AGE (2000 TO I4OO B.C.) I II. EPIC AGE (14OO TO 80O B.C.) l 5 III. AGE OF LAWS AND PHILOSOPHY (80O TO 3 I 5 B.C. 2 5 IV. RISE OF BUDDHISM (522 B.C.) 36 V. BUDDHIST AGE (3 I 5 B.C. TO A.D. 500) . 49 VI. PURANIC AGE (a.D. 5OO TO 800) . 65 VII. AGE OF RAJPUT ASCENDENCY (a.D. 800 TO 1200 79 VIII. AGE OF THE AFGHAN RULE (a.D. 1206 TO I 526 89 IX. CONDITION OF THE PEOPLE UNDER THE AFGHA1 RULE ...... 99 X. AGE OF THE MOGHAL RULE (a.D. I 526 TO I707 106 XI. CONDITION OF THE PEOPLE UNDER THE MOGHAL RULE ....... 116 XII. AGE OF MAHRATTA ASCENDENCY (a.D. 1 7 1 8 TO l8l8) 132 Index 144 ' LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS PAGE Asoka's Pillar 54 Chaitya or Church at Karli Chaitya or Church at Ajanta . -

Yonas and Yavanas in Indian Literature Yonas and Yavanas in Indian Literature

YONAS AND YAVANAS IN INDIAN LITERATURE YONAS AND YAVANAS IN INDIAN LITERATURE KLAUS KARTTUNEN Studia Orientalia 116 YONAS AND YAVANAS IN INDIAN LITERATURE KLAUS KARTTUNEN Helsinki 2015 Yonas and Yavanas in Indian Literature Klaus Karttunen Studia Orientalia, vol. 116 Copyright © 2015 by the Finnish Oriental Society Editor Lotta Aunio Co-Editor Sari Nieminen Advisory Editorial Board Axel Fleisch (African Studies) Jaakko Hämeen-Anttila (Arabic and Islamic Studies) Tapani Harviainen (Semitic Studies) Arvi Hurskainen (African Studies) Juha Janhunen (Altaic and East Asian Studies) Hannu Juusola (Middle Eastern and Semitic Studies) Klaus Karttunen (South Asian Studies) Kaj Öhrnberg (Arabic and Islamic Studies) Heikki Palva (Arabic Linguistics) Asko Parpola (South Asian Studies) Simo Parpola (Assyriology) Rein Raud (Japanese Studies) Saana Svärd (Assyriology) Jaana Toivari-Viitala (Egyptology) Typesetting Lotta Aunio ISSN 0039-3282 ISBN 978-951-9380-88-9 Juvenes Print – Suomen Yliopistopaino Oy Tampere 2015 CONTENTS PREFACE .......................................................................................................... XV PART I: REFERENCES IN TEXTS A. EPIC AND CLASSICAL SANSKRIT ..................................................................... 3 1. Epics ....................................................................................................................3 Mahābhārata .........................................................................................................3 Rāmāyaṇa ............................................................................................................25 -

Women in Hindu Dharma- a Tribute

Women in Hindu Dharma- a Tribute Respected Ladies and Gentlemen1, Namaste! Women and the Divine Word:- Let me start my talk with a recitation from the Vedas2, the ‘Divinely Exhaled’ texts of Hindu Dharma – Profound thought was the pillow of her couch, Vision was the unguent for her eyes. Her wealth was the earth and Heaven, When Surya (the sun-like resplendent bride) went to meet her husband.3 Her mind was the bridal chariot, And sky was the canopy of that chariot. Orbs of light were the two steers that pulled the chariot, When Surya proceeded to her husband’s home!4 The close connection of women with divine revelation in Hinduism may be judged from the fact that of the 407 Sages associated with the revelation of Rigveda, twenty-one5 are women. Many of these mantras are quite significant for instance the hymn on the glorification of the Divine Speech.6 The very invocatory mantra7 of the Atharvaveda8 addresses divinity as a ‘Devi’ – the Goddess, who while present in waters, fulfills all our desires and hopes. In the Atharvaveda, the entire 14th book dealing with marriage, domestic issues etc., is attributed to a woman. Portions9 of other 19 books are also attributed to women sages10. 1 It is a Hindu tradition to address women before men in a group, out of reverence for the former. For instance, Hindu wedding invitations are normally addressed ‘To Mrs. and Mr. Smith’ and so on and not as ‘To Mr. And Mrs. Smith’ or as ‘ To Mr. and Mrs. John Smith’ or even as ‘To Mrs. -

<H1>The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa By

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa by Kisari Mohan Ganguli (Translator) The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa by Kisari Mohan Ganguli (Translator) Produced by David King, Juliet Sutherland, and Charles Franks, John B. Hare and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa Translated into English Prose from the Original Sanskrit Text by Kisari Mohan Ganguli [1883-1896] page 1 / 802 Scanned at sacred-texts.com, 2003. Redaction at Distributed Proofing, Juliet Sutherland, Project Manager. Additional proofing and formatting at sacred-texts.com, by J. B. Hare. This text is in the public domain. These files may be used for any non-commercial purpose, provided this notice of attribution is left intact. TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE The object of a translator should ever be to hold the mirror upto his author. That being so, his chief duty is to represent so far as practicable the manner in which his author's ideas have been expressed, retaining if possible at the sacrifice of idiom and taste all the peculiarities of his author's imagery and of language as well. In regard to translations from the Sanskrit, nothing is easier than to dish up Hindu ideas, so as to make them agreeable to English taste. But the endeavour of the present translator has been to give in the following pages as literal a rendering as possible of the great work of Vyasa. To the purely English reader there is much in the following pages that will strike as ridiculous. Those unacquainted with any language but their own are generally very exclusive in matters of taste. -

Dharma in the Mahabharata As a Response to Ecological Crises: a Speculation

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The Trumpeter - Journal of Ecosophy (Athabasca University) Dharma in the Mahabharata as a response to Ecological Crises: A speculation By Kamesh Aiyer Abstract Without doing violence to Vyaasa, the Mahabharata (Vyaasa, The Mahabharata 1933-1966) can be properly viewed through an ecological prism, as a story of how “Dharma” came to be established as a result of a conflict over social policies in response to on-going environmental/ecological crises. In this version, the first to recognize the crises and to attempt to address them was Santanu, King of Hastinapur (a town established on the banks of the Ganges). His initial proposals evoked much opposition because draconian and oppressive, and were rescinded after his death. Subsequently, one of Santanu’s grandsons, Pandu, and his children, the Pandavas, agreed with Santanu that the crises had to be addressed and proposed more acceptable social policies and practices. Santanu’s other grandson, Dhritarashtra, and his children, the Kauravas, disagreed, believing that nothing needed to be done and opposed the proposed policies. The fight to establish these policies culminated in the extended and widespread “Great War” (the “Mahaa-Bhaarata”) that was won by the Pandavas. Some of the proposed practices/social policies became core elements of "Hinduism" (such as cow protection and caste), while others became accepted elements of the cultural landscape (acceptance of the rights of tribes to forests as “commons”). Still other proposals may have been implied but never became widespread (polyandry) or may have been deemed unacceptable and immoral (infanticide). -

Autochthonous Aryans? the Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts

Michael Witzel Harvard University Autochthonous Aryans? The Evidence from Old Indian and Iranian Texts. INTRODUCTION §1. Terminology § 2. Texts § 3. Dates §4. Indo-Aryans in the RV §5. Irano-Aryans in the Avesta §6. The Indo-Iranians §7. An ''Aryan'' Race? §8. Immigration §9. Remembrance of immigration §10. Linguistic and cultural acculturation THE AUTOCHTHONOUS ARYAN THEORY § 11. The ''Aryan Invasion'' and the "Out of India" theories LANGUAGE §12. Vedic, Iranian and Indo-European §13. Absence of Indian influences in Indo-Iranian §14. Date of Indo-Aryan innovations §15. Absence of retroflexes in Iranian §16. Absence of 'Indian' words in Iranian §17. Indo-European words in Indo-Iranian; Indo-European archaisms vs. Indian innovations §18. Absence of Indian influence in Mitanni Indo-Aryan Summary: Linguistics CHRONOLOGY §19. Lack of agreement of the autochthonous theory with the historical evidence: dating of kings and teachers ARCHAEOLOGY __________________________________________ Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies 7-3 (EJVS) 2001(1-115) Autochthonous Aryans? 2 §20. Archaeology and texts §21. RV and the Indus civilization: horses and chariots §22. Absence of towns in the RV §23. Absence of wheat and rice in the RV §24. RV class society and the Indus civilization §25. The Sarasvatī and dating of the RV and the Bråhmaas §26. Harappan fire rituals? §27. Cultural continuity: pottery and the Indus script VEDIC TEXTS AND SCIENCE §28. The ''astronomical code of the RV'' §29. Astronomy: the equinoxes in ŚB §30. Astronomy: Jyotia Vedåga and the -

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa Translated into English Prose from the Original Sanskrit Text. By Kisari Mohan Ganguli [1883-1896] TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE The object of a translator should ever be to hold the mirror upto his author. That being so, his chief duty is to represent so far as practicable the manner in which his author's ideas have been expressed, retaining if possible at the sacrifice of idiom and taste all the peculiarities of his author's imagery and of language as well. In regard to translations from the Sanskrit, nothing is easier than to dish up Hindu ideas, so as to make them agreeable to English taste. But the endeavour of the present translator has been to give in the following pages as literal a rendering as possible of the great work of Vyasa. To the purely English reader there is much in the following pages that will strike as ridiculous. Those unacquainted with any language but their own are generally very exclusive in matters of taste. Having no knowledge of models other than what they meet with in their own tongue, the standard they have formed of purity and taste in composition must necessarily be a narrow one. The translator, however, would ill-discharge his duty, if for the sake of avoiding ridicule, he sacrificed fidelity to the original. He must represent his author as he is, not as he should be to please the narrow taste of those entirely unacquainted with him. Mr. Pickford, in the preface to his English translation of the Mahavira Charita, ably defends a close adherence to the original even at the sacrifice of idiom and taste against the claims of what has been called 'Free Translation,' which means dressing the author in an outlandish garb to please those to whom he is introduced. -

Rajaji-Mahabharata.Pdf

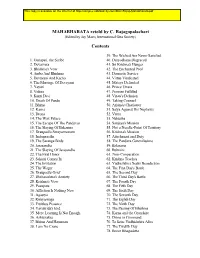

MAHABHARATA retold by C. Rajagopalachari (Edited by Jay Mazo, International Gita Society) Contents 39. The Wicked Are Never Satisfied 1. Ganapati, the Scribe 40. Duryodhana Disgraced 2. Devavrata 41. Sri Krishna's Hunger 3. Bhishma's Vow 42. The Enchanted Pool 4. Amba And Bhishma 43. Domestic Service 5. Devayani And Kacha 44. Virtue Vindicated 6. The Marriage Of Devayani 45. Matsya Defended 7. Yayati 46. Prince Uttara 8. Vidura 47. Promise Fulfilled 9. Kunti Devi 48. Virata's Delusion 10. Death Of Pandu 49. Taking Counsel 11. Bhima 50. Arjuna's Charioteer 12. Karna 51. Salya Against His Nephews 13. Drona 52. Vritra 14. The Wax Palace 53. Nahusha 15. The Escape Of The Pandavas 54. Sanjaya's Mission 16. The Slaying Of Bakasura 55. Not a Needle-Point Of Territory 17. Draupadi's Swayamvaram 56. Krishna's Mission 18. Indraprastha 57. Attachment and Duty 19. The Saranga Birds 58. The Pandava Generalissimo 20. Jarasandha 59. Balarama 21. The Slaying Of Jarasandha 60. Rukmini 22. The First Honor 61. Non-Cooperation 23. Sakuni Comes In 62. Krishna Teaches 24. The Invitation 63. Yudhishthira Seeks Benediction 25. The Wager 64. The First Day's Battle 26. Draupadi's Grief 65. The Second Day 27. Dhritarashtra's Anxiety 66. The Third Day's Battle 28. Krishna's Vow 67. The Fourth Day 29. Pasupata 68. The Fifth Day 30. Affliction Is Nothing New 69. The Sixth Day 31. Agastya 70. The Seventh Day 32. Rishyasringa 71. The Eighth Day 33. Fruitless Penance 72. The Ninth Day 34. Yavakrida's End 73. -

Authorship, History, and Race in Three Contemporary Retellings of the Mahabharata

Authorship, History, and Race in Three Contemporary Retellings of the Mahabharata: The Palace of Illusions, The Great Indian Novel, and The Mahabharata (Television Mini Series) A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Nandaka M. Kalugampitiya August 2016 © 2016 Nandaka M. Kalugampitiya. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Authorship, History, and Race in Three Contemporary Retellings of the Mahabharata: The Palace of Illusions, The Great Indian Novel, and The Mahabharata (Television Mini Series) by NANDAKA M. KALUGAMPITIYA has been approved for Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by Vladimir Marchenkov Professor of Interdisciplinary Arts Elizabeth Sayrs Interim Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 Abstract KALUGAMPITIYA, NANDAKA M., Ph.D., August 2016, Interdisciplinary Arts Authorship, History, and Race in Three Contemporary Retellings of the Mahabharata: The Palace of Illusions, The Great Indian Novel, and The Mahabharata (Television Mini Series) Director of Dissertation: Vladimir Marchenkov In this study, I explore the manner in which contemporary artistic reimaginings of the Sanskrit epic the Mahabharata with a characteristically Western bent intervene in the dominant discourse on the epic. Through an analysis of Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni’s The Palace of Illusions (2008), Shashi Tharoor’s The Great Indian Novel (1989), and Peter Brook’s theatrical production The Mahabharata (1989 television mini-series), I argue that these reimaginings represent a tendency to challenge the cultural authority of the Sanskrit epic in certain important ways. The study is premised on the recognition that the three works of art in question respond, some more consciously than others, to three established assumptions regarding the Mahabharata respectively: (1) the Sanskrit epic as a product of divine authorship; (2) the Sanskrit epic as history; and (3) the Sanskrit epic as the story of a particular race. -

Draupadi and Dhrishtadyumna

דראופדי http://img2.tapuz.co.il/CommunaFiles/34934883.pdf دراوبادي دروپدی द्रौपदी د ر وپد ی http://uh.learnpunjabi.org/default.aspx द्रौपदी ਦਰੋਪਤੀ http://h2p.learnpunjabi.org/default.aspx دروپتی فرشتہ ਦਰੋਪਤੀ ਫ਼ਰਰਸ਼ਤਾ http://g2s.learnpunjabi.org/default.aspx DRUPADA… Means "wooden pillar" or "firm footed" in Sanskrit. In the Hindu epic the 'Mahabharata' this is the name of a king of Panchala, the father of Draupadi and Dhrishtadyumna http://www.behindthename.com/name/drupada DRAUPADI Means "daughter of DRUPADA" in Sanskrit. http://www.behindthename.com/name/draupadi Draupadi - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Draupadi Draupadi From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Draupadi (Sanskrit: 6ौपदी , draupad ī, Sanskrit pronunciation: [d ̪ rəʊ pəd̪ i]) is described as the chief female Draupadi protagonist or heroine in the Hindu epic, Mahabharata .[1] According to the epic, she is the "fire born" daughter of Drupada, King of Panchala and also became the common wife of the five Pandavas. She was the most beautiful woman of her time. Draupadi had five sons; one by each of the Pandavas: Prativindhya from Yudhishthira, Sutasoma from Bheema, Srutakarma from Arjuna, Satanika from Nakula, and Srutasena from Sahadeva. Some people say that she too had two daughters after the Upapandavas, Shutanu from Yudhishthira and Pragiti from Arjuna although this is a debatable concept in the Mahabharata. Draupadi is considered as one of the Panch-Kanyas or Five Virgins. [2] She is also venerated as a village goddess Draupadi Amman. Draupadi, -

Sathya Sai Speaks, Volume 1

Glossary eanings of Sanskrit words used in discussing religious and philosophical topics, more particularly used Min the discourses by Sri Sathya Sai Baba, reproduced in this volume, are given in this glossary. While the English equivalents for the Sanskrit words have been given in the text with reference to the context, this glossary attempts to provide comprehensive meanings and detailed explanations of the more important Sanskrit words, for the benefit of lay readers who are interested in Hindu religion and philosophy. Ahalya. Princess of the Puru dynasty, who was turned into a stone by the curse of her husband, Gautama, for suspected adultery. She regained her form when Rama touched the stone with his divine feet. Aham Brahmasmi. “I am Brahman”. This is one of the great Vedic aphorisms (mahavakyas). ahimsa. Nonviolence. amritha. Divine nectar (literally, no death or immortal). ananda. Divine bliss. The Self is unalloyed, eternal bliss. Pleasures are but its faint and impermanent shadows. Anjaneya. A name for Hanuman. aradhana. Divine service; propitiation. Arjuna. Krishna’s disciple, in the Bhagavad Gita; third of five Pandava brothers. SeeMahabharatha . a-santhi. Lack of peace; agitated mind; restlessness. Opposite of santhi. Atma. Self; Soul. Self, with limitations, is the individual soul. Self, with no limitations, is Brahman, the Su- preme Reality. Avatar. Incarnation of God. Whenever there is a decline of dharma, God comes down to the world assuming bodily form to protect the good, punish the wicked and re-establish dharma. An Avatar is born and lives free and is ever conscious of His mission. By His precept and example, He opens up new paths in spirituality, shedding His grace on all.