Wool Bale Stencils : a Design History of New Zealand Branding and Visual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory Cant Ranch Historic District John Day Fossil Beds National Monument 2009

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2009 Cant Ranch Historic District John Day Fossil Beds National Monument ____________________________________________________ Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary and Site Plan Inventory Unit Description ................................................................................................................ 2 Site Plans ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Park Information ............................................................................................................................... 5 Concurrence Status Inventory Status ............................................................................................................................... 6 Geographic Information and Location Map Inventory Unit Boundary Description ............................................................................................... 6 State and County ............................................................................................................................. 7 Size .................................................................................................................................................. 7 Boundary UTMS ............................................................................................................................... 8 Location Map ................................................................................................................................. -

The Establishment of the Canterbury Society of Arts

New Zealand Journal of History, 44, 2 (2010) The Establishment of the Canterbury Society of Arts FORMING THE TASTE, JUDGEMENT AND IDENTITY OF A PROVINCE, 1850–1880 HISTORIES OF NEW ZEALAND ART have commonly portrayed art societies as conservative institutions, predominantly concerned with educating public taste and developing civic art collections that pandered to popular academic British painting. In his discussion of Canterbury’s cultural development, for example, Jonathan Mane-Wheoki commented that the founding of the Canterbury Society of Arts (CSA) in 1880 formalized the enduring presence of the English art establishment in the province.1 Similarly, Michael Dunn has observed that the model for the establishment of New Zealand art societies in the late nineteenth century was the Royal Academy, London, even though ‘they were never able to attain the same prestige or social significance as the Royal Academy had in its heyday’.2 As organizations that appeared to perpetuate the Academy’s example, art societies have served as a convenient, reactionary target for those historians who have contrasted art societies’ long-standing conservatism with the struggle to establish an emerging national identity in the twentieth century. Gordon Brown, for example, maintained that the development of painting within New Zealand during the 1920s and 1930s was restrained by the societies’ influence, ‘as they increasingly failed to comprehend the changing values entering the arts’.3 The establishment of the CSA in St Michael’s schoolroom in Christchurch on 30 June 1880, though, was more than a simple desire by an ambitious colonial township to imitate the cultural and educational institutions of Great Britain and Europe. -

Worker Exposure to Dusts and Bioaerosols in the Sheep Shearing Industry in Eastern NSW

Worker Exposure to Dusts and Bioaerosols in the Sheep Shearing Industry in Eastern NSW. by Ryan Kift BAppSc (Hons) (Occupational Health and Environment) BAppSc (Environmental Health) A thesis presented in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2007 CERTIFICATE OF ORIGINALITY The text of this thesis contains no material which has been accepted as part of the requirements for another degree or diploma in any University, or material previously published or written by another author unless due reference to this material has been made. Ryan Kift 2 March 2007 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my family, supervisors, friends and colleagues that helped and supported me throughout this study. Thank you to the University of Western Sydney for their financial, academic and resource support. Thank you to all of the people involved in the sheep shearing industry that participated in this study. Without the help and support of all of these people this study would not have been possible. iii ABSTRACT The air found in a sheep shearing environment is normally contaminated with many different airborne substances. These contaminants include dust (predominantly organic), bioaerosols (fungi and bacteria) and gases (ammonia and carbon monoxide). Respiratory disorders, such as Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis, chronic bronchitis and asthma, have been associated with exposure to the types of airborne contaminants found in a normal sheep shearing environment. The majority of Australian and international research in the livestock handling industries that has investigated dust exposure has focused on the poultry and pig industries. Some worldwide studies have been undertaken on feedlot cattle. Research in the sheep shearing industry in relation to worker exposure data for airborne contaminants has been identified as a major need as no documented studies have been undertaken anywhere in the world. -

2020 Supply Catalog

2020 Supply Catalog 1-800-841-9665 | (614) 834-2006 | www.midstateswoolgrowers.com The sheep industry has seen many changes in the past 100 years. Mid-States Wool Growers Cooperative has been here to witness all these changes and to continue to provide quality products at a fair price with excellent service. As we begin our next century, let’s look back at the events that have shaped Mid-States Wool Growers Cooperative into the company that it is today. 1918 Parent wool marketing organization, Tri-State Wool Growers was formed. 1921 First cooperative warehouse was purchased for $125,000 in Columbus, Ohio. 1931 Midwest Wool Marketing Cooperative—an organization that played a major role in the current cooperative—was organized in Kansas City, Missouri. 1945 Tri-State Wool Growers was reorganized and the name was changed to the Ohio Wool Growers Cooperative Association. 1957 Ohio Wool Growers added a livestock supply division, which provided the Midwestern sheep producer with supplies and equipment needed to make sheep operations more efficient and successful. 1958 A new 60,000 sq. ft. warehouse was built at Groves Road in Columbus. This building utilized some of the most efficient wool grading and marketing technology available at the time. 1969 Ohio Wool Growers added a new, industry related retail clothing store known as Woolen Square. 1974 Ohio Wool Growers Association and Midwest Wool Marketing Cooperative joined forces through a merger that resulted in the new and stronger organization being named Mid-States Wool Growers Cooperative. The merger added a warehouse in South Hutchinson, Kansas as well as a livestock supply division operated by Midwest. -

New Zealand National Board

CUTTING EDGE Issue No 71 | July 2019 New Zealand National Board Nicola Hill (Chair) FROM THE CHAIR Future Directions INSIDE n March, the New Zealand National Health Boards, politicians and the public to THIS ISSUE IBoard (NZNB) held a strategy planning raise awareness of these issues. We hope to workshop, with elected members, show the value of our generalists and raise 2 Gordon Gordon-Taylor specialty society representatives, the profile of surgeons who work across Prize community and co-opted members the breadth of their vocational scope. We attending. Under the guidance of Allan are aware of concerns around the numbers 3 Surgery 2019 Panting, we identified priorities for the of New Zealanders selected for binational NZNB for the next five years. Along training programmes and plan to continue 6 EDSA Corner with overall RACS strategy and policy, discussion of this issue. the NZNB Strategic Plan guides our The next section is ‘Connections’. We want 7 RACS Trainees responses to national and College issues, to improve the Board’s communications Association update and provides a focus for NZNB activities. and engagement with Fellows, Trainees It highlights the issues we feel are and International Medical Graduates 8 Activities of the NZ important for New Zealand surgeons and (IMGs), specialist societies, and the New National Board New Zealanders. The document informs Zealand health community and strengthen the direction for the NZNB and New 10 Success In The its advocacy on surgical health issues. We Zealand office staff. The current plan is would like to improve the level and quality Fellowship still in draft form, but will soon be on the of communications and engagement. -

An Annotated Bibliography of Published Sources on Christchurch

Local history resources An annotated bibliography of published sources on the history of Christchurch, Lyttelton, and Banks Peninsula. Map of Banks Peninsula showing principal surviving European and Maori place-names, 1927 From: Place-names of Banks Peninsula : a topographical history / by Johannes C. Andersen. Wellington [N.Z.] CCLMaps 536127 Introduction Local History Resources: an annotated bibliography of published sources on the history of Christchurch, Lyttelton and Banks Peninsula is based on material held in the Aotearoa New Zealand Centre (ANZC), Christchurch City Libraries. The classification numbers provided are those used in ANZC and may differ from those used elsewhere in the network. Unless otherwise stated, all the material listed is held in ANZC, but the pathfinder does include material held elsewhere in the network, including local history information files held in some community libraries. The material in the Aotearoa New Zealand Centre is for reference only. Additional copies of many of these works are available for borrowing through the network of libraries that comprise Christchurch City Libraries. Check the catalogue for the classification number used at your local library. Historical newspapers are held only in ANZC. To simplify the use of this pathfinder only author and title details and the publication date of the works have been given. Further bibliographic information can be obtained from the Library's catalogues. This document is accessible through the Christchurch City Libraries’ web site at https://my.christchurchcitylibraries.com/local-history-resources-bibliography/ -

Research Theme: the Life of Shepherds and Sheep Farmers

CULTURE AND NATURE: THE EUROPEAN HERITAGE OF SHEEP FARMING AND PASTORAL LIFE RESEARCH THEME: THE LIFE OF SHEPHERDS AND SHEEP FARMERS RESEARCH REPORT FOR THE UK By Gemma Bell and Simon Bell Estonian University of Life Sciences November 2011 The CANEPAL project is co-funded by the European Commission, Directorate General Education and Culture, CULTURE 2007-2013.Project no: 508090-CU-1-2010-1-HU-CULTURE-VOL11 This report reflects the authors’ view and the Commission is not liable for any use that may be made of the information contained herein 1. INTRODUCTION Since the agricultural revolution, the reorganisation of land use patterns, the Highland clearances (when most people in the Scottish Highlands were removed from the land and replaced by sheep flocks) sheep farming has become a branch of “normal” farming with resident farmers and employed shepherds. Since the land used for sheep farming is normally spatially connected to the farmstead and since also the sheep breeds are hardy and stay outside all year round there is no need to move them long distances to summer pastures or for shepherds to tend them and stay away from home. Thus the kind of activities and the life of shepherds found in some European countries have no place in Britain. However, that is not to say that the life of a sheep farmer is easy and that it may not be a solitary and lonely occupation set in a remote hill region. Sheep farming in the UK can be divided generally between upland and lowland activities. Upland farmers normally breed sheep and sell the lambs to lowland farmers for “finishing”, that is fattened up to the optimum weight for slaughter. -

The Effect of Time of Shearing on Wool Production and Management of a Spring-Lambing Merino Flock

The Effect of Time of Shearing on Wool Production and Management of a Spring-lambing Merino Flock Angus John Dugald Campbell, BVSc(Hons) BAnimSc Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2006 University of Melbourne School of Veterinary Science © Angus Campbell, 2006 ABSTRACT Choice of shearing time is one of the major management decisions for a wool-producing Merino flock and affects many aspects of wool production and sheep health. Previous studies have investigated the effect of shearing on only a few of these factors at a time, so that there is little objective information at the flock level for making rational decisions on shearing time. This is particularly the case for flocks that lamb in spring, the preferred time in south-eastern Australia. A trial was conducted in a self-replacing, fine wool Merino flock in western Victoria, from January 1999 to May 2004, comparing ewes shorn annually in December, March or May. Within each of these shearing times, progeny were shorn in one of two different patterns, aligning them with their adult shearing group by 15–27 months of age. Time of shearing did not consistently improve the staple strength of wool. December-shorn ewes produced significantly lighter and finer fleeces (average 19.1 µm, 3.0 kg clean weight), whereas fleeces from March-shorn ewes were heavier and coarser (19.4 µm, 3.1 kg). Fleeces from ewes shorn in May were of similar weight to fleeces from March-shorn ewes (3.1 kg), but they were of significantly broader diameter (19.7 µm). -

Boolcoomatta Reserve CLICK WENT the SHEARS

Boolcoomatta Reserve CLICK WENT THE SHEARS A social history of Boolcoomatta Station, 1857 to 2020 Judy D. Johnson Editor: Eva Finzel Collated and written by Judy Johnson 2019 Edited version by Eva Finzel 2021 We acknowledge the Adnyamathanha People and Wilyakali People as the Traditional Owners of what we know as Boolcoomatta. We recognise and respect the enduring relationship they have with their lands and waters, and we pay our respects to Elders past, present and future. Front page map based on Pastoral Run Sheet 5, 1936-1964, (163-0031) Courtesy of the State Library of South Australia Bush Heritage Australia Level 1, 395 Collins Street | PO Box 329 Flinders Lane Melbourne, VIC 8009 T: (03) 8610 9100 T: 1300 628 873 (1300 NATURE) F: (03) 8610 9199 E: [email protected] W: www.bushheritage.org.au Content Author’s note and acknowledgements viii Editor’s note ix Timeline, 1830 to 2020 x Conversions xiv Abbreviations xiv An introduction to Boolcoomatta 1 The Adnyamathanha People and Wilyakali People 4 The European history of Boolcoomatta 6 European settlement 6 From sheep station to a place of conservation 8 Notes 9 Early explorers, surveyors and settlers, 1830 to 1859 10 Early European exploration and settlement 10 Goyder’s discoveries and Line 11 Settlement during the 1800s 13 The shepherd and the top hats The Tapley family, 1857 to 1858 14 The shepherds 15 The top hats 16 The Tapleys’ short lease of Boolcoomatta 16 Thomas and John E Tapley's life after the sale of Boolcoomatta 17 Boolcoomatta’s neighbours in 1857 18 The timber -

Sheep Shearing and Basic Care 101 Student Handbook

Sheep Shearing and Basic Care 101 Student Handbook Written by Alison Smith and Trevor Hollenback, Instructors Photo by Paige Green by Paige Photo Fibershed University of California Dept. of Agriculture and Natural Resources Hopland Research and Extension Center Development of curriculum and production of this course handbook have been made possible by generous funding from Fibershed. A heartfelt ‘thank you’ goes out to them for this support and the work they do. Fibershed develops regional and regenerative fiber systems on behalf of independent working producers, by expanding opportunities to implement carbon farming, forming catalytic foundations to rebuild regional manufacturing, and through connecting end-users to farms and ranches through public education. For more information, visit fibershed.org Table of Contents Introduction – page 2 SECTION 1 – Sheep Care and Management, by Alison Smith – page 3 SECTION 2 – Shearing Sheep, by Trevor Hollenback – page 13 APPENDIX A – Glossary of Terms, by Trevor Hollenback – page 53 APPENDIX B – Sample Sheep Management Calendars, by Alison Smith – page 55 Photo by Paige Green by Paige Photo Sheep Shearing and Basic Care 101 1 Introduction to this Handbook his handbook has been written as a supplemental document for students going through the Sheep Shearing Tand Basic Care 101 course at the UCANR Hopland Research and Extension Center. It is not a standalone how-to book, but rather a document intended to serve as your notes for this course. All of the primary principles covered in this course can be found in this handbook, saving you valuable time and energy that might have been spent diligently taking notes during class. -

Shearing Magazine on Line At

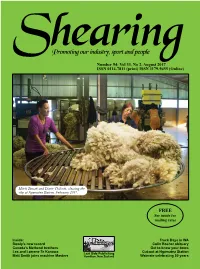

Read Shearing magazine on line at www.lastsidepublishing.co.nz Shearing Promoting our industry, sport and people Number 94: Vol 33, No 2, August 2017 ISSN 0114-7811 (print) ISSN 1179-9455 (Online) Mitch Tamati and Diane Chilcott, classing the clip at Ngamatea Station, February 2017. FREE See inside for mailing rates Inside: Truck Days in WA Rowly’s new record Colin Bosher obituary Canada’s Metheral brothers Get to know your bows Les and Lorrene Te Kanawa Last Side Publishing Cut-out at Ngamatea Station Matt Smith joins machine Masters Hamilton, New Zealand Waimate celebrating 50 years Shearing 1 Read Shearing magazine on line at www.lastsidepublishing.co.nz SAFETY. FIRST. Shearing shed safety starts with the No.1 & most trusted name in shearing Search Heiniger Shed Safety on YouTube EVO Shearing Plant - Winner of 2 Worksafe Industry Awards - Unique electronic safety switch - Designed to eliminate handpiece lockups - Proven choice for commercial shearing contractors in Australia and New Zealand TPW Xpress Woolpress - Safety screen guard with automatic return - Presses more weight into less packs - Fast pack locking system - Automatic bale pinning and bale ejection - Contamination-free short square bales Put Shed Safety First! Get in to your local stockists or call is today! Heiniger New Zealand | 1B Chinook Place, Hornby, Christchurch 8042 | +64 3 349 8282 | www.heiniger.com Shearing 2 Read Shearing magazine on line at www.lastsidepublishing.co.nz Number 94: Vol 33, No 2, August 2017 Promoting our industry, sport and people Shearing ISSN 0114 - 7811 (print) ISSN 1179 - 9455 (online) CONTENTS UNDER COVER STORY 4 NZ Wool Classers’ Association Greetings readers and welcome to our August 2017 6 Something to do with old combs edition of the magazine. -

Mount Peel Station 1856-1982

Lincoln University Digital Dissertation Copyright Statement The digital copy of this dissertation is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This dissertation may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: you will use the copy only for the purposes of research or private study you will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of the dissertation and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate you will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from the dissertation. U"N(;OLN UNlVERS1TY UBRAR1 S;'\N-rE:(~:t:~urf)'. ~~.Z. MOUNT PEEL STATION 1856-1982 A HISTORICAL STUDY OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF A HIGH-COUNTRY RUN IN CANTERBURY, NEW ZEALAND. Gillian Wilson B. Hort. CONTENTS PART I: 6. Shel ter 7. Access roads PART I (A) 8. Technology INTRODUCTION AND LOCATION 9. Buildings 10. Weeds and pests 11. Runholders' attitudes PART I (B) PART II (C) NATURAL ELEMENTS INFLUENCING THE LANDSCAPE SUMMARY 1. Cl imate 2. Geology PART III: THE MOUNT PEEL STATION HOMESTEAD 3. Topography 4. Soil s 5. The natural vegetation of Mount Peel 1. Site selection criteria 2. The homesteads of Mount Peel Station PART I (C) 3. The Church of the Holy Innocents THE POLYNESIAN INFLUENCE ON THE 4. The homestead garden NATURAL LANDSCAPE PART IV: A PHOTOGRAPHIC SURVEY PART II: STATION DEVELOPMENT AND AGRICULTURAL PRACTICES AFFECTING THE LANDSCAPE APPENDIX PART II (A) EARLY STATION HISTORY BIBLIOGRAPHY PART II (B) AGRICULTURAL PRACTICES AFFECTING THE APPEARANCE OF THE LANDSCAPE 1.