Migrating Banjaras and Settling Tandas: an Un-Noticed Contribution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Historical Transition of Banjara Community in India with Special Reference to South India Nagaveni T

Research Journal of Recent Sciences _________________________________________________ ISSN 2277-2502 Vol. 4(ISC-2014), 11-15 (2015) Res. J. Recent. Sci. A Historical Transition of Banjara Community in India with Special Reference to South India Nagaveni T. Department of History, Government First Grade College, Kuvempunagar, Mysore-570 023, INDIA Available online at: www.isca.in, www.isca.me Received 13 rd November 2014, revised 9th March 2015, accepted 25 th March 2015 Abstract An incisive insight into the literature on Banjara Community clearly indicates that ample literature has been produced by the Western and Indian scholars. Yet the treatment of the problem is exponential. Deep delve into the process of historical transition of the Banjara Community enables us to focus on various controversial issues and complexities of historical significance. Issues like Semantics, Historicity, Location, Ethnicity, Categorization, Caste-clan, Dichotomy and the community’s identity continued to gravitate the attention of the scholars and researchers alike. Lack of unanimity among the scholars and policy makers on these contentious issues has added perplexity to the puzzle. Ambiguous explanations given by the community historians have further complicated the clear-cut understanding of the process of historical transition. The antiquity of this Banjara Community is traceable to Harappa and Mohenjodaro. Its influence continued to spread and retain its relevance down the centuries to shape and reshape the course of history. There is a speculation about the group of Banjaras who mere concentrated outside India and called as Roma Gypsy, where their social history is not yet clear but proved to be of Indian Origin. This paper however strives to focus on historical transition within the context of India from 13 th Century A.D. -

Solid Waste Management Exposure Workshop for Urban Local Bodies Of

Title of the report Final Report 2018TR15 Solid waste management exposure workshop for urban local bodies of Uttar Pradesh under Swachh Bharat Mission of the Government of India Proceeding of workshop at Agra, 27-29 November, 2018 Supported by / Prepared for National Institute of Urban Affairs (NIUA) i © The Energy and Resources Institute 2018 Suggested format for citation T E R I. 2018 Solid waste management exposure workshops for ULBs of Uttar Pradesh New Delhi: The Energy and Resources Institute. 353 pp. [Project Report No. 2018RT15] For more information Project Monitoring Cell T E R I Tel. 2468 2100 or 2468 2111 Darbari Seth Block E-mail [email protected] IHC Complex, Lodhi Road Fax 2468 2144 or 2468 2145 New Delhi – 110 003 Web www.teriin.org India India +91 • Delhi (0)11 ii Table of contents 1. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Workshop at Agra ............................................................................................................ 2 2. PROCEEDINGS ............................................................................................................................ 4 2.1 Number of Participants ................................................................................................... 4 2.2 Profile of Participants ....................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Consolidated Feedback ................................................................................................... -

O.I.H. Government of India Ministry of Housing & Urban Affairs Lok Sabha Unstarred Question No. 3376 to Be Answered On

O.I.H. GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF HOUSING & URBAN AFFAIRS LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO. 3376 TO BE ANSWERED ON JANUARY 01, 2019 SLUMS IN U.P. No. 3376. SHRI BHOLA SINGH: Will the Minister of HOUSING AND URBAN AFFAIRS be pleased to state: (a) whether slums have been identified in the State of Uttar Pradesh, as per 2011 census; (b) if so, the details thereof, location-wise; and (c) the number of people living in the said slums? ANSWER THE MINISTER OF STATE (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) OF THE MINISTRY OF HOUSING & URBAN AFFAIRS [SHRI HARDEEP SINGH PURI] **** (a) to (c): As per the Census-2011, number of slum households was 10,66,363 and slum population was 62,39,965 in the State of Uttar Pradesh. City-wise number of slum households and slum population in the State of Uttar Pradesh are at Annexure. ****** Annexure referred in reply to LSUQ No. 3376 due for 1.1.2018 City -wise number of Slum Households and Slum Population in the State of Uttar Pradesh as per Census 2011 Sl. Town No. of Slum Total Slum Area Name No. Code Households Population 1 120227 Noida (CT) 11510 49407 2 800630 Saharanpur (M Corp.) 12308 67303 3 800633 Nakur (NPP) 1579 9670 4 800634 Ambehta (NP) 806 5153 5 800635 Gangoh (NPP) 1277 7957 6 800637 Deoband (NPP) 4759 30737 7 800638 Nanauta (NP) 1917 10914 8 800639 Rampur Maniharan (NP) 3519 21000 9 800642 Kairana (NPP) 1731 11134 10 800643 Kandhla (NPP) 633 4128 11 800670 Afzalgarh (NPP) 75 498 12 800672 Dhampur (NPP) 748 3509 13 800678 Thakurdwara (NPP) 2857 18905 14 800680 Umri Kalan (NP) 549 3148 15 800681 Bhojpur Dharampur -

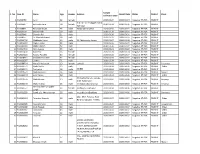

S. No. Case ID Name Age Gender Address Sample Collection Date

Sample S. No. Case ID Name Age Gender Address Result Date Status District Block Collection Date 1 PIL006482 Azmi 32 female 2020-03-24 2020-03-24 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT H.N.181 Vill-Shahgarh tahsil 2 PIL006617 Balvinder Kaur 58 female 2020-02-04 2020-02-06 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT Kalinagar 3 PIL006621 Balvinder Singh 45 male Haidarpur Amariya 2020-03-19 2020-03-21 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 4 PIL006709 Bhairo Nath 60 male 2020-03-29 2020-03-30 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 5 PIL007046 Chandra Pal 21 male 2020-03-30 2020-03-31 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 6 PIL008157 Dr. Mustak Ahmad 38 male 2020-03-25 2020-03-25 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 7 PIL0011730 Mahboob Hasan 33 male 33 Chidiyadah, Neoria 2020-03-07 2020-03-08 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 8 PIL0013307 Mohd. Aafaq 55 male 2020-03-26 2020-03-27 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 9 PIL0013311 Mohd. Akram 52 male 2020-03-26 2020-03-27 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 10 PIL0014401 Nitin Kapoor 34 male 2020-03-21 2020-03-22 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 11 PIL0017400 Rubeena 26 female 2020-03-24 2020-03-24 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 12 PIL0017401 Rubina Parveen 46 female 2020-03-26 2020-03-27 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 13 PIL0018711 Shabeena Parveen 42 female 2020-03-26 2020-03-27 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 14 PIL0021387 Usman 71 male 2020-03-24 2020-03-24 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT 15 PIL0088704 Neha D/ indra pal 19 female tarkothi 2020-04-02 2020-04-03 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT Puranpur 16 PIL0090571 Mohd.Sahib 15 male 2020-04-04 2020-04-06 Negative RT-PCR PILIBHIT Other 17 PIL0090572 RoshanLal 28 male नो डेटा 2020-04-04 2020-04-06 -

Population Density in Ambedkar Nagar District: a Geographical Analysis

ZENITH International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research ____________ISSN 2231-5780 Vol.7 (11), November (2017), pp. 285-293 Online available at zenithresearch.org.in POPULATION DENSITY IN AMBEDKAR NAGAR DISTRICT: A GEOGRAPHICAL ANALYSIS DR. VIMAL KUMAR JAISWAL D.PHIL. DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY, UNIVERSITY OF ALLAHABAD, ALLAHABAD ,UTTAR PRADESH, INDIA. ABSTRACT Ambedkar Nagar District is a newly constructed but densely populated district. Densely populated areas have great stress on natural resources resulting in failure of public distribution system and anarchy in various forms posing the area as underdeveloped however such areas are the great source of man power which could be converted into resources. Plain areas such as the region are often having dense population due to easy availability of agricultural land and water resources but the population density has certain variation at micro level due to various local conditions. The present study is an attempt to know the population density pattern and resource potential areas in the region. KEY WORDS: Agricultural Density, Ambedkar Nagar District, Arithmetic Density, Physiological Density, Population Density. REFERENCES CHANDANA, R. C. & SINDHU, M. S. 1980. Introduction to Populaton Geography, New Delhi, Kalyani Pubishers. CLARKE, J. I. 1972. Population Geography, Oxfoard, Pergamon Press. CRAIG, J. 1972. Population Potential and Population Density. Area, 4, 10-12. DEMKO, G. J. 1970. Population Geography: A Reader, New York, Mc Graw-Hill Company. HAWLEY, A. H. 1972. Population Density and the City. Demography, 9, 521-529. KLASEN, S. & NESTMANN, T. 2006. Population, Population Density and Technological Change. Journal of Population Economics, 19, 611-626. ZENITH International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research ____________ISSN 2231-5780 Vol.7 (11), November (2017), pp. -

Gypsies of India in Need of Love

BANJARA/GYPSIES OF INDIA THE MOST RESPONSIVE GROUP TO GOSPEL, YET REMAIN UNREACHED The first Banjara/Gypsy M.Th Graduate under Senate of Serampore University, India. A happy moment Greetings Dear Friends In Christ, Greetings in the name of our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ. I am indeed happy to meet you through this presentation and share about Gypsies and their longing for Salvation in Jesus Christ. Banjara are one of the largest ethnic community, under different groups scattered all over India and in most European countries. The European Gypsy trace their origin to Western India who have migrated between 12th -13th century. Majority Banjara live in Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra. As they live outside of the mainstream social system, they are hardly reached by outsiders, even by the gospel of Jesus. Further, their secluded social life, religious and cultural customs and practices, peculiar characteristics, keep them away from non-Banjara. Banjara people are one of the most backward, uneducated, poor, suffer severe health care, kill girl child and they are discriminated both by casteism and racially. Education level is very low among them. There are very few theologically trained Banjara pastors working among their own people. I The Beulah Ministries was began in 2009 to work for Banjara people in state of Karnataka and also in partnership with other churches. The focus of ministry was among rural villages and children. It had a very good beginning and many children accepted Jesus. Due to lack of sponsors and funds the ministry was closed, and the congregation was handed over to another church. -

Bareilly Dealers Of

Dealers of Bareilly Sl.No TIN NO. UPTTNO FIRM - NAME FIRM-ADDRESS 1 09107300009 BE0001281 RAJ CROCKERY CENTER HOSPITAL ROAD BAREILLY 2 09107300014 BE0008385 SUPER PROVISION STORE PANJABI MARKET, BAREILLY. 3 09107300028 BE0006987 BHATIA AGEMCIES 89 CIVIL LINES, BAREILLY. 4 09107300033 BE0010659 VIJAY KIRANA STORE SUBHAS NAGAR BY 5 09107300047 BE0001030 MUKUT MURARI LAL WOOD VIKRATA CHOUPLA ROAD BY 6 09107300052 BE0008979 GARG BROTHERS TOWN HALL BAREILLY. 7 09107300066 BE0001244 RAJ BOOK DEPOT SUBHAS MKT BY 8 09107300071 BE0000318 MONICA MEDICAL STORE 179, CIVIL LINES, BAREILLY. 9 09107300085 BE0001762 RAM KUMAR SUBASH CHAND AONLA ,BAREILLY. 10 09107300090 BE0009124 GARU NANA FILLING STN KARGANA BAREILLY. 11 09107300099 BE0005657 KHANDUJA ENTERPRISES GANJ AONLA,BAREILLY. 12 09107300108 BE0004857 ADARSH RTRADING CO. CHOPUPLA ROAD BY 13 09107300113 BE0007245 SWETI ENTERPRISES CHOUPLA ROAD BY 14 09107300127 BE0011496 GREEN MEDICAL STORE GHER ANNU KHAN AONLA BAREILLY 15 09107300132 BE0002007 RAMESHER DAYAL SURENDRA BHAV AONLA BAREILLY 16 09107300146 BE0062544 INDIAN FARMERS FERTILISERS CORP AONLA, BAREILLY. LTD 17 09107300151 BE0007079 BHARAT MECH STORE BALIA AONLA, BAREILLY. 18 09107300165 BE0011395 SUCHETA PRAKASHAN MANDIR BAZAR GANJ AONLA BAREILLY 19 09107300170 BE0003628 KICHEN CENTER & RAPAIRS JILA PARISAD BY 20 09107300179 BE0006421 BAREILLY GUN SERVICE 179/10 CIVIL LINES,BAREILLY 21 09107300184 BE0004554 AHUJA GAS & FAMILY APPLIANCES 179 CIVIL LINES, BAREILLY. 22 09107300198 BE0002360 IJAAT KHA CONTRACTOR SIROLY AONLA BAREILLY. 23 09107300207 BE0003604 KRISHAN AUTAUR CONTRACTOR BAMANPURI BAREILLY. 24 09107300212 BE0009945 PUSTAK MANDIR SUBASH MKT BY 25 09107300226 BE0005758 NITIN FANCY JEWELERS CANAAT PLACE MKT BY 26 09107300231 BE0005520 DEHLI AUTO CENTER CAROLAAN CHOUPLA ROAD BY 27 09107300245 BE0003248 KHANN A PLYWOOD EMPORIUM CIVIL LINES, BAREILLY. -

Fact Sheets Fact Sheets

DistrictDistrict HIV/AIDSHIV/AIDS EpidemiologicalEpidemiological PrProfilesofiles developeddeveloped thrthroughough DataData TTriangulationriangulation FFACTACT SHEETSSHEETS MaharastraMaharastra National AIDS Control Organisation India’s voice against AIDS Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India 6th & 9th Floors, Chandralok Building, 36, Janpath, New Delhi - 110001 www.naco.gov.in VERSION 1.0 GOI/NACO/SIM/DEP/011214 Published with support of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention under Cooperative Agreement No. 3U2GPS001955 implemented by FHI 360 District HIV/AIDS Epidemiological Profiles developed through Data Triangulation FACT SHEETS Maharashtra National AIDS Control Organisation India’s voice against AIDS Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India 6th & 9th Floors, Chandralok Building, 36, Janpath, New Delhi - 110001 www.naco.gov.in December 2014 Dr. Ashok Kumar, M.D. F.I.S.C.D & F.I.P.H.A Dy. Director General Tele : 91-11-23731956 Fax : 91-11-23731746 E-mail : [email protected] FOREWORD The national response to HIV/AIDS in India over the last decade has yielded encouraging outcomes in terms of prevention and control of HIV. However, in recent years, while declining HIV trends are evident at the national level as well as in most of the States, some low prevalence and vulnerable States have shown rising trends, warranting focused prevention efforts in specific areas. The National AIDS Control Programme (NACP) is strongly evidence-based and evidence-driven. Based on evidence from ‘Triangulation of Data’ from multiple sources and giving due weightage to vulnerability, the organizational structure of NACP has been decentralized to identified districts for priority attention. The programme has been successful in creating a robust database on HIV/AIDS through the HIV Sentinel Surveillance system, monthly programme reporting data and various research studies. -

BANJARA STASTICAL REPORT KARNATKA STATE Report

BANJARA STASTICAL REPORT KARNATKA STATE Report Submitted to Mr. Rahul Gandhi General Secretary All India Congress Committee New Delhi BY Dr. Chandrashekar Naik Dr.D Paramesha Naik B.E,M.Tech,M.B.A,M.Phil Ph.D M.Sc, M.Phil, Ph.D, FISEC Congress & Banjara – Activist Congress & Banjara – Activist Mobile: +91-9379945100 Mobile: +91-9844250997 [email protected] [email protected] 2012 About Banjaras The Banjaras are the largest and historic formed group in India and also known as Lambadi or Lambani. The Banjara people are a people who speak lambadi or Lambani. All gypsy languages are linked linguistically, stemming from ancient Sanskrit and belonging to the North Indo-Aryan language family. Lambadi is the heart language of the Banjara, but it has no written script. The Banjara speak a second language of the state they live in and adopt that script. They are listed under 53 different names. Historically, these are the root Gypsies of earth. During the British colonial rule, these gypsy nomads of India were given the name Banjara, but they call themselves Ghor. The Banjaras are a colourful, versatile and one of the largest people groups of India, inhabiting most of the districts in India. The Banjara are a sturdy, ambitious people and have a light complexion. The Banjara were historically nomadic, keeping cattle, trading salt and transporting goods. Most of these people now have settled down to farming and various types of wage labour. Their habits of living in isolated groups away from other, which was a characteristic of their nomadic days, still persist. -

Annual Plan 2009-10

INDEX ANNUAL PLAN 2014-15 PART-I Chapter Subject Page No. No. Section – I General 1 Annual Plan 2014-15 – At a Glance 1-3 2 Economic Outline of Maharashtra 4-6 3 Planning Process 7-12 4 Central Assistance/Institutional Finance External Aided 13-17 Projects 5 Decentralization of Planning (District Planning) 18-20 6 Schedule Caste Sub-Plan 21-24 7 Tribal Sub Plan 25-28 8 Statutory Development Boards and Removal of Backlog 29-35 9 Woman and Child Development 36-42 10 Western Ghat and Hilly Area Development Programme 43-47 11 Human Development Index 48-50 Section 2 Sector wise 1 Agriculture and Allied Services 1-55 2 Rural Development 56-62 3 Special Area Development Programme 63 4 Water Resources and Flood Control 64-65 5 Power Development 66-79 6 Industry and Mining 80-94 7 Transport and Communication 95-102 8 Science, Technology and Environment 103-111 9 General Economic Services 112-125 10 Social and Community Services 126-237 11 General Services 238-246 ANNUAL PLAN 2014-15 AT A GLANCE Introduction: 1.1.1 Preparation and implementation of Five Year Plans and Annual Plans is one of the most important instruments for General Economic Development of the State. The main objective of planning is to create employment opportunities, improve standard of living of the people below the poverty line, and attain self-reliance and creation to infrastructure. 1.1.2 Size of Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007-12) was determined at Rs.1,27,538/- crore. However, sum of the Annual Plans from year 2007-08 to 2011-12 sanctioned by the Planning Commission arrived actually at Rs.1,61,124/- crore. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email Id Remarks 9421864344 022 25401313 / 9869262391 Bhaveshwarikar

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 10001 SALPHALE VITTHAL AT POST UMARI (MOTHI) TAL.DIST- Male DEFAULTER SHANKARRAO AKOLA NAME REMOVED 444302 AKOLA MAHARASHTRA 10002 JAGGI RAMANJIT KAUR J.S.JAGGI, GOVIND NAGAR, Male DEFAULTER JASWANT SINGH RAJAPETH, NAME REMOVED AMRAVATI MAHARASHTRA 10003 BAVISKAR DILIP VITHALRAO PLOT NO.2-B, SHIVNAGAR, Male DEFAULTER NR.SHARDA CHOWK, BVS STOP, NAME REMOVED SANGAM TALKIES, NAGPUR MAHARASHTRA 10004 SOMANI VINODKUMAR MAIN ROAD, MANWATH Male 9421864344 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 GOPIKISHAN 431505 PARBHANI Maharashtra 10005 KARMALKAR BHAVESHVARI 11, BHARAT SADAN, 2 ND FLOOR, Female 022 25401313 / bhaveshwarikarmalka@gma NOT RENEW RAVINDRA S.V.ROAD, NAUPADA, THANE 9869262391 il.com (WEST) 400602 THANE Maharashtra 10006 NIRMALKAR DEVENDRA AT- MAREGAON, PO / TA- Male 9423652964 RENEWAL UP TO 2018 VIRUPAKSH MAREGAON, 445303 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10007 PATIL PREMCHANDRA PATIPURA, WARD NO.18, Male DEFAULTER BHALCHANDRA NAME REMOVED 445001 YAVATMAL MAHARASHTRA 10008 KHAN ALIMKHAN SUJATKHAN AT-PO- LADKHED TA- DARWHA Male 9763175228 NOT RENEW 445208 YAVATMAL Maharashtra 10009 DHANGAWHAL PLINTH HOUSE, 4/A, DHARTI Male 9422288171 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 SUBHASHKUMAR KHANDU COLONY, NR.G.T.P.STOP, DEOPUR AGRA RD. 424005 DHULE Maharashtra 10010 PATIL SURENDRANATH A/P - PALE KHO. TAL - KALWAN Male 02592 248013 / NOT RENEW DHARMARAJ 9423481207 NASIK Maharashtra 10011 DHANGE PARVEZ ABBAS GREEN ACE RESIDENCY, FLT NO Male 9890207717 RENEWAL UP TO 05/06/2018 402, PLOT NO 73/3, 74/3 SEC- 27, SEAWOODS, -

A Geographical Study of Trends in Sex Ratio of Gondia District of Maharashtra State

Volume 5, Issue 5, May – 2020 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology ISSN No:-2456-2165 A Geographical Study of Trends in Sex Ratio of Gondia District of Maharashtra State Ankitkumar N. Jaiswal Rajani A. Chaturvedi Research Student, Head and Associate Professor R.T.M. Nagpur University, P.G. Department of Geography, N.M.D. College, Gondia, Nagpur, India Maharashtra, India Abstract:- In assessing the quality of life and levels of decades. Also, lot of variation was observed in rural and development of a particular region sex ratio plays pivotal urban sex ratio in Gondia District. role. It also influences the other population characteristics such as migration, occupation structure, Number of females per 1000 males in the age group 0- volume and nature of social need and employment. In 6 years is termed as Child Sex ratio. In India there has been the present study, the spatio-temporal variations in the a decreasing trend of the Child sex ratio after independence. sex ratio of Gondia District of Maharashtra State were The main reason behind this disturbing fact is due to the son analyzed using secondary sources of data. Also, light was preference in the society. Although the child sex ratio of shed on child sex ratio. The sex ratio of Gondia district Gondia district showed decrease but it was at lower rate. was always higher than that of the Maharashtra state from year 1901 to 2011 whereas child sex ratio turned II. OBJECTIVES out to be very low. Gondia is among those districts which show the trend of higher sex ratio over decades.