ED032179.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1922 Elizabeth T

co.rYRIG HT, 192' The Moootainetro !scot1oror,d The MOUNTAINEER VOLUME FIFTEEN Number One D EC E M BER 15, 1 9 2 2 ffiount Adams, ffiount St. Helens and the (!oat Rocks I ncoq)Ora,tecl 1913 Organized 190!i EDITORlAL ST AitF 1922 Elizabeth T. Kirk,vood, Eclttor Margaret W. Hazard, Associate Editor· Fairman B. L�e, Publication Manager Arthur L. Loveless Effie L. Chapman Subsc1·iption Price. $2.00 per year. Annual ·(onl�') Se,·ent�·-Five Cents. Published by The Mountaineers lncorJ,orated Seattle, Washington Enlerecl as second-class matter December 15, 19t0. at the Post Office . at . eattle, "\Yash., under the .-\0t of March 3. 1879. .... I MOUNT ADAMS lllobcl Furrs AND REFLEC'rION POOL .. <§rtttings from Aristibes (. Jhoutribes Author of "ll3ith the <6obs on lltount ®l!!mµus" �. • � J� �·,,. ., .. e,..:,L....._d.L.. F_,,,.... cL.. ��-_, _..__ f.. pt",- 1-� r�._ '-';a_ ..ll.-�· t'� 1- tt.. �ti.. ..._.._....L- -.L.--e-- a';. ��c..L. 41- �. C4v(, � � �·,,-- �JL.,�f w/U. J/,--«---fi:( -A- -tr·�� �, : 'JJ! -, Y .,..._, e� .,...,____,� � � t-..__., ,..._ -u..,·,- .,..,_, ;-:.. � --r J /-e,-i L,J i-.,( '"'; 1..........,.- e..r- ,';z__ /-t.-.--,r� ;.,-.,.....__ � � ..-...,.,-<. ,.,.f--· :tL. ��- ''F.....- ,',L � .,.__ � 'f- f-� --"- ��7 � �. � �;')'... f ><- -a.c__ c/ � r v-f'.fl,'7'71.. I /!,,-e..-,K-// ,l...,"4/YL... t:l,._ c.J.� J..,_-...A 'f ',y-r/� �- lL.. ��•-/IC,/ ,V l j I '/ ;· , CONTENTS i Page Greetings .......................................................................tlristicles }!}, Phoiitricles ........ r The Mount Adams, Mount St. Helens, and the Goat Rocks Outing .......................................... B1/.ith Page Bennett 9 1 Selected References from Preceding Mount Adams and Mount St. -

Washington Division of Geology and Earth Resources Open File Report 74-1

TEPHRA OF SALMON SPRINGS AGE FROM THE SOUTHEASTERN OLYMPIC PENINSULA, WASHINGTON by R. U. BIRDSEYE and R. J. CARSON North Carolina State University WASHINGTON DIVISION OF GEOLOGY AND EARTH RESOURCES OPEN FILE REPORT 74-1 1974 This report has not been edited or reviewed for conformity with Division of Geology and Earth Resources standards and nomenclature Revised October, 1989 CONTENTS Page Abstract •.•................••......••........•.......•............• 1 Introduction ....................................................... 1 Acknowledgments •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 1 Pleistocene climate, glaciation, and volcanism ••••••••••••••••••••• 2 The ashes: Their thickness, distribution, and stratigraphic position •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 7 Color and texture of the ash ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 14 Deposition of the ash •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 14 Atmospheric conditions during deposition of the ash •••••••••••••••• 20 Usefulness of volcanic ash in stratigraphic determination •••••••••• 21 Canel us ion ....•••.•..••••.••..••......•.••••••.••••....•••••...••.. 21 References cited ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 23 ILLUSTRATIONS Figure 1 - Maximum extent of the Cordilleran ice sheet •••••••••••• 3 Figure 2 - Summary of late Pleistocene events in western Washington ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 4 Figure 3 - Location map showing inferred extent of minimum areas of fallout of volcanic ash from eruptions of Mount Mazama and Glacier Peak ••••••••••••••••••••••• -

The Complete Script

Feb rua rg 1968 North Cascades Conservation Council P. 0. Box 156 Un ? ve rs i ty Stat i on Seattle, './n. 98 105 SCRIPT FOR NORTH CASCAOES SLIDE SHOW (75 SI Ides) I ntroduct Ion : The North Cascades fiountatn Range In the State of VJashington Is a great tangled chain of knotted peaks and spires, glaciers and rivers, lakes, forests, and meadov;s, stretching for a 150 miles - roughly from Pt. fiainier National Park north to the Canadian Border, The h undreds of sharp spiring mountain peaks, many of them still unnamed and relatively unexplored, rise from near sea level elevations to seven to ten thousand feet. On the flanks of the mountains are 519 glaciers, in 9 3 square mites of ice - three times as much living ice as in all the rest of the forty-eight states put together. The great river valleys contain the last remnants of the magnificent Pacific Northwest Rain Forest of immense Douglas Fir, cedar, and hemlock. f'oss and ferns carpet the forest floor, and wild• life abounds. The great rivers and thousands of streams and lakes run clear and pure still; the nine thousand foot deep trencli contain• ing 55 mile long Lake Chelan is one of tiie deepest canyons in the world, from lake bottom to mountain top, in 1937 Park Service Study Report declared that the North Cascades, if created into a National Park, would "outrank in scenic quality any existing National Park in the United States and any possibility for such a park." The seven iiiitlion acre area of the North Cascades is almost entirely Fedo rally owned, and managed by the United States Forest Service, an agency of the Department of Agriculture, The Forest Ser• vice operates under the policy of "multiple use", which permits log• ging, mining, grazing, hunting, wt Iderness, and alI forms of recrea• tional use, Hov/e ve r , the 1937 Park Study Report rec ornmen d ed the creation of a three million acre Ice Peaks National Park ombracing all of the great volcanos of the North Cascades and most of the rest of the superlative scenery. -

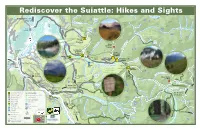

Rediscover the Suiattle: Hikes and Sights

Le Conte Chaval, Mountain Rediscover the Suiattle:Mount Hikes and Sights Su ia t t l e R o Crater To Marblemount, a d Lake Sentinel Old Guard Hwy 20 Peak Bi Buckindy, Peak g C reek Mount Misch, Lizard Mount (not Mountain official) Boulder Boat T Hurricane e Lake Peak Launch Rd na Crk s as C en r G L A C I E R T e e Ba P E A K k ch e l W I L D E R N E S S Agnes o Mountain r C Boulder r e Lake e Gunsight k k Peak e Cub Trailhead k e Dome e r Lake Peak Sinister Boundary e C Peak r Green Bridge Put-in C y e k Mountain c n u Lookout w r B o e D v Darrington i Huckleberry F R Ranger S Mountain Buck k R Green Station u Trailhead Creek a d Campground Mountain S 2 5 Trailhead Old-growth Suiattle in Rd Mounta r Saddle Bow Grove Guard een u Gr Downey Creek h Mountain Station lp u k Trailhead S e Bannock Cr e Mountain To I-5, C i r Darrington c l Seattle e U R C Gibson P H M er Sulphur S UL T N r S iv e uia ttle R Creek T e Falls R A k Campground I L R Mt Baker- Suiattle d Trailhead Sulphur Snoqualmie Box ! Mountain Sitting Mountain Bull National Forest Milk n Creek Mountain Old Sauk yo Creek an North Indigo Bridge C Trailhead To Suiattle Closure Lake Lime Miners Ridge White Road Mountain No Trail Chuck Access M Lookout Mountain M I i Plummer L l B O U L D E R Old Sauk k Mountain Rat K Image Universal C R I V E R Trap Meadow C Access Trail r Lake Suiattle Pass Mountain Crystal R e W I L D E R N E S S e E Pass N Trailhead Lake k Sa ort To Mountain E uk h S Meadow K R id Mountain T ive e White Chuck Loop Hwy ners Cre r R i ek R M d Bench A e Chuc Whit k River I I L Trailhead L A T R T Featured Trailheads Land Ownership S To Holden, E Other Trailheads National Wilderness Area R Stehekin Fire C Mountain Campgrounds National Forest I C Beaver C I F P A Fortress Boat Launch State Conservation Lake Pugh Mtn Mountain Trailhead Campground Other State Road Helmet Butte Old-growth Lakes Mt. -

WDFW Washington State Recovery Plan for the Lynx

STATE OF WASHINGTON March 2001 LynxLynx RecoveryRecovery PlanPlan by Derek Stinson Washington Department of FISH AND WILDLIFE Wildlife Program Wildlife Diversity Division WDFW 735 In 1990, the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission adopted procedures for listing and delisting species as endangered, threatened, or sensitive and for writing recovery and management plans for listed species (WAC 232-12-297, Appendix C). The lynx was classified by the Washington Fish and Wildlife Commission as a threatened species in 1993 (Washington Administrative Code 232-12-011). The procedures, developed by a group of citizens, interest groups, and state and federal agencies, require that recovery plans be developed for species listed as threatened or endangered. Recovery, as defined by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, is “the process by which the decline of an endangered or threatened species is arrested or reversed, and threats to its survival are neutralized, so that its long-term survival in nature can be ensured.” This document summarizes the historic and current distribution and abundance of the lynx in Washington, describes factors affecting the population and its habitat, and prescribes strategies to recover the species in Washington. The draft state recovery plan for the lynx was reviewed by researchers and state and federal agencies. This review was followed by a 90 day public comment period. All comments received were considered in preparation of this final recovery plan. For additional information about lynx or other state listed species, contact: Manager, Endangered Species Section Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife 600 Capitol Way N Olympia WA 98501-1091 This report should be cited as: Stinson, D. -

Geology of the Northern Part of the Southeast Three Sisters

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Karl C. Wozniak for the degree of Master of Science the Department cf Geology presented on February 8, 1982 Title: Geology of the Northern Part of the Southeast Three Sisters Quadrangle, Oregon Redacted for Privacy Abstract approved: E. M. Taylorc--_, The northern part of the Southeast Three Sisters quadrangle strad- dles the crest of the central High Cascades of Oregon. The area is covered by Pleistocene and Holocene volcanic and volcaniclastic rocks that were extruded from a number of composite cones, shield volcanoes, and cinder cones. The principal eruptive centers include Sphinx Butte, The Wife, The Husband, and South Sister volcanoes. Sphinx Butte, The Wife, and The Husband are typical High Cascade shield and composite vol- canoes whose compositions are limited to basalt and basaltic andesite. South Sister is a complex composite volcano composed of a diverse assem- blage of rocks. In contrast with earlier studies, the present investi- gation finds that South Sister is not a simple accumulation of andesite and dacite lavas; nor does the eruptive sequence display obvious evolu- tionary trends or late stage divergence to basalt and rhyolite. Rather, the field relations indicate that magmas of diverse composition have been extruded from South Sister vents throughout the lifespan of this volcano. The compositional variation at South Sister is. atypical of the Oregon High Cascade platform. This variation, however, represents part of a continued pattern of late Pliocene and Pleistocene magmatic diver- sity in a local region that includes Middle Sister, South Sister, and Broken Top volcanoes. Regional and local geologic constraints combined with chemical and petrographic criteria indicate that a local subcrustal process probably produced the magmas extruded fromSouth Sister, whereas a regional subcrustal process probably producedthe magmas extruded from Sphinx Butte, The Wife, and The Husband. -

Seattle Backpacking Washington Experience

Route Details for the Bronze Backpack, Silver Backpack, and Gold Backpack Award Badges Because the objective of the badges is to experience the variety of backpacking regions available in Washington, it’s not necessary to do each route exactly as described in the Routes & Places database or the references. A trip that follows approximately the same route with extensions or minor variations can be substituted. However, for routes whose descriptions include a “Key Experience” alternate routes must include that experience in order to qualify. Reference(s) Region Route Distance Gain Days Key Experience Notes WTA Books Olympic Peninsula Beaches 100 Classic Hikes in Washington, 2nd Edition #99 Olympic Coast North: The Shipwreck Coast 20.2 260 3 North Coast Route Backpacking Washington 1st Edition #1 South Coast Wilderness Trail - 100 Classic Hikes: Washington, 3rd Edition #2 Olympic Coast South: The Wildcatter Coast 17.5 1900 3 Toleak Point Backpacking Washington 1st Edition #2 Ozette Triangle 9.4 400 2 Cape Alava Loop (Ozette Triangle) 100 Classic Hikes: Washington, 3rd Edition #3. Shi Shi Beach and Point of the Shi Shi Beach 8.8 200 2 Arches 100 Classic Hikes: Washington, 3rd Edition #4. Olympic Peninsula Inland 100 Classic Hikes: Washington, 3rd Edition #6 Enchanted Valley 26.5 1800 3 Enchanted Valley Backpacking Washington #3 Spend at least one night in the Seven 100 Classic Hikes: Washington, 3rd Edition #8 Seven Lakes Basin 20 4000 3 Lakes Basin area. High Divide Loop Backpacking Washington #4 100 Classic Hikes in Washington 2nd Edition #98 Upper Lena Lake 14 3900 2 Upper Lena Lake Backpacking Washington #11 Hoh River to Glacier Meadows Walk the Hoh River Trail and camp at 34 4500 4 Glacier Meadows. -

Hiking Guide

HIKING GUIDE A guide to some of the best hikes in the Pacific Northwest 1 TABLE OF 28 Glacier Peak Meadows THE SEATTLE NORTHCOUNTRY 30 Old Sauk Trail CONTENTS Eight Mile Creek & Squire Creek Pass WILDERNESS PLEDGE 31 2 What to Pack 32 Fortson Ponds & Whitehorse Trail 2 How to Hike 34 Suiattle River & Image Lake Hiking Regions 36 Monte Cristo I will pack out everything I pack in. 4 38 Lime Kiln Garbage kills wildlife and destroys waterways. COASTAL 40 River Meadows County Park I will not disturb branches in the rivers. 6 COMMUNITIES SKYKOMISH/ Salmon use these areas to lay eggs. 8 Jetty Island 42 SNOHOMISH 10 Big Gulch RIVER VALLEYS 11 Japanese Gulch I will take selfies without harming myself. 44 Paradise Valley Conservation Area Do not get close to cliff edges or wildlife. 12 Spencer Island 46 Lake Dorothy 14 Kayak Point County Park 48 Lord Hill Regional Park 16 Meadowdale Beach I will not feed or touch wildlife. 49 Sultan River Canyon Trail Human food can harm our furry and feathered friends. STILLAGUAMISH/ 50 Bridal Veil Falls & Lake Serene 18 SAUK RIVER VALLEYS 52 Evergreen Mountain Lookout I will not go off the trail. 53 Johnson Ridge & Scorpion Mountain 20 Nakashima Barn It’s easier than you might think to get lost. 54 West Cady Ridge 21 Cutthroat Lake Flowing Lake Park Big Four Ice Caves 55 I will pick up after my dog. 22 Mount Dickerman Dogs feces destroys the enviorment by... 23 URBAN 24 Barlow Point 56 BASECAMP 25 Goat Lake I will pack the ten essentials. -

Crater Lake National Park Oregon

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR HUBERT WORK. SECRETARY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE STEPHEN T. MATHER. DIRECTOR RULES AND REGULATIONS CRATER LAKE NATIONAL PARK OREGON PALISADE POINT, MOUNT SCOTT IN THE DISTANCE 1923 Season from July 1 to September 30 THE PHANTOM SHIP. FISHING IS EXCELLENT IN CRATER LAKE. THE NATIONAL PARKS AT A GLANCE. [Number, 19; total area, 11,372 square miles.] Area in National parks in Distinctive characteristics. order of creation. Location. squaro miles. Hot Springs Middle Arkansas li 40 hot springs possessing curative properties- 1832 Many hotels and boarding houses—20 bath houses under public control. Yellowstone Northwestern Wyo 3.348 More geysers than in all rest of world together- 1872 ming. Boiling springs—Mud volcanoes—Petrified for ests—Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, remark able for gorgeous coloring—Large lakes—Many largo streams and waterfalls—Vast wilderness, greatest wild bird and animal preserve in world— Exceptional trout fishing. Sequoia. Middle eastern Cali 252 The Big Tree National Park—several hundred 1S90 fornia. sequoia trees over 10 feet in diameter, some 25 to 36 feet, hi diameter—Towering mountain ranges- Startling precipices—Mile long cave of delicate beauty." Yosemito Middle eastern Cali 1,125 Valley of world-famed beauty—Lofty chits—Ro 1890 fornia. mantic vistas—Many waterfalls of extraordinary height—3 groves of big trees—High Sierra— Waterwhcol falls—Good trout fishing. General Grant Middle eastern Cali 4 Created to preserve the celebrated General Grant 1S90 fornia. Tree, 3* feet in diameter—6 miles from Sequoia National Park. Mount Rainier ... West central Wash 321 Largest accessible single peak glacier system—28 1899 ington. -

Volcanic Hazards • Washington State Is Home to Five Active Volcanoes Located in the Cascade Range, East of Seattle: Mt

CITY OF SEATTLE CEMP – SHIVA GEOLOGIC HAZARDS Volcanic Hazards • Washington State is home to five active volcanoes located in the Cascade Range, east of Seattle: Mt. Baker, Glacier Peak, Mt. Rainier, Mt. Adams and Mt. St. Helens (see figure [Cascades volcanoes]). Washington and California are the only states in the lower 48 to experience a major volcanic eruption in the past 150 years. • Major hazards caused by eruptions are blast, pyroclastic flows, lahars, post-lahar sedimentation, and ashfall. Seattle is too far from any volcanoes to receive damage from blast and pyroclastic flows. o Ash falls could reach Seattle from any of the Cascades volcanoes, but prevailing weather patterns would typically blow ash away from Seattle, to the east side of the state. However, to underscore this uncertainty, ash deposits from multiple pre-historic eruptions have been found in Seattle, including Glacier Peak (less than 1 inch) and Mt. Mazama/Crater Lake (amount unknown) ash. o The City of Seattle depends on power, water, and transportation resources located in the Cascades and Eastern Washington where ash is more likely to fall. Seattle City Light operates dams directly east of Mt. Baker and in Pend Oreille County in eastern Washington. Seattle’s water comes from two reservoirs located on the western slopes of the Central Cascades, so they are outside the probable path of ashfall. o If heavy ash were to fall over Seattle it would create health problems, paralyze the transportation system, destroy many mechanical objects, endanger the utility networks and cost millions of dollars to clean up. Ash can be very dangerous to aviation. -

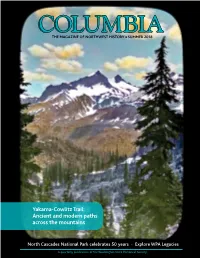

Yakama-Cowlitz Trail: Ancient and Modern Paths Across the Mountains

COLUMBIA THE MAGAZINE OF NORTHWEST HISTORY ■ SUMMER 2018 Yakama-Cowlitz Trail: Ancient and modern paths across the mountains North Cascades National Park celebrates 50 years • Explore WPA Legacies A quarterly publication of the Washington State Historical Society TWO CENTURIES OF GLASS 19 • JULY 14–DECEMBER 6, 2018 27 − Experience the beauty of transformed materials • − Explore innovative reuse from across WA − See dozens of unique objects created by upcycling, downcycling, recycling − Learn about enterprising makers in our region 18 – 1 • 8 • 9 WASHINGTON STATE HISTORY MUSEUM 1911 Pacific Avenue, Tacoma | 1-888-BE-THERE WashingtonHistory.org CONTENTS COLUMBIA The Magazine of Northwest History A quarterly publication of the VOLUME THIRTY-TWO, NUMBER TWO ■ Feliks Banel, Editor Theresa Cummins, Graphic Designer FOUNDING EDITOR COVER STORY John McClelland Jr. (1915–2010) ■ 4 The Yakama-Cowlitz Trail by Judy Bentley OFFICERS Judy Bentley searches the landscape, memories, old photos—and President: Larry Kopp, Tacoma occasionally, signage along the trail—to help tell the story of an Vice President: Ryan Pennington, Woodinville ancient footpath over the Cascades. Treasurer: Alex McGregor, Colfax Secretary/WSHS Director: Jennifer Kilmer EX OFFICIO TRUSTEES Jay Inslee, Governor Chris Reykdal, Superintendent of Public Instruction Kim Wyman, Secretary of State BOARD OF TRUSTEES Sally Barline, Lakewood Natalie Bowman, Tacoma Enrique Cerna, Seattle Senator Jeannie Darneille, Tacoma David Devine, Tacoma 14 Crown Jewel Wilderness of the North Cascades by Lauren Danner Suzie Dicks, Belfair Lauren14 Danner commemorates the 50th22 anniversary of one of John B. Dimmer, Tacoma Washington’s most special places in an excerpt from her book, Jim Garrison, Mount Vernon Representative Zack Hudgins, Tukwila Crown Jewel Wilderness: Creating North Cascades National Park. -

1968 Mountaineer Outings

The Mountaineer The Mountaineer 1969 Cover Photo: Mount Shuksan, near north boundary North Cascades National Park-Lee Mann Entered as second-class matter, April 8, 1922, at Post Office, Seattle, Wash., under the Act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly and semi-monthly during June by The Mountaineers, P.O. Box 122, Seattle, Washington 98111. Clubroom is at 7191h Pike Street, Seattle. Subscription price monthly Bulletin and Annual, $5.00 per year. EDITORIAL STAFF: Alice Thorn, editor; Loretta Slat er, Betty Manning. Material and photographs should be submitted to The Mountaineers, at above address, before Novem ber 1, 1969, for consideration. Photographs should be black and white glossy prints, 5x7, with caption and photographer's name on back. Manuscripts should be typed double-spaced and include writer's name, address and phone number. foreword Since the North Cascades National Park was indubi tably the event of this past year, this issue of The Mountaineer attempts to record aspects of that event. Many other magazines and groups have celebrated by now, of course, but hopefully we have managed to avoid total redundancy. Probably there will be few outward signs of the new management in the park this summer. A great deal of thinking and planning is in progress as the Park Serv ice shapes its policies and plans developments. The North Cross-State highway, while accessible by four wheel vehicle, is by no means fully open to the public yet. So, visitors and hikers are unlikely to "see" the changeover to park status right away. But the first articles in this annual reveal both the thinking and work which led to the park, and the think ing which must now be done about how the park is to be used.