Interview of Mary Belle Guthrie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Logs for Station KUWR Type Date Details Audio Received 10/01/18 Matched Filter RWT, Received from CAP

11/16/2018 ENDEC Log Start: 09/30/2018 Sent Not CAP End: 10/06/2018 Required Per page: 100 show prev next tab file xml file Print This Page Logs for Station KUWR Type Date Details Audio Received 10/01/18 Matched filter RWT, Received from CAP. Log Only. 11:00:10 The Civil Authorities have issued a Required Weekly T est for all of Arizona, all of Colorado, all of Idaho, all of Montana, all of New Mexico, all of Utah, and all of Wyoming beginning at 11:00 am Mon Oct 1 and ending at 12:00 pm Mon Oct 1 (fromcap). CAP Server: IP AWS CAP Reference ID: IP [email protected],RWT_MDT_1538413200000,20181001T11:00:00 06:00 CAP T ext: Test Message IPAWS OPEN CAP EAS Feed Configuration Test Message Received 10/02/18 Required Weekly Test, Matched filter OTHERS, Received on Monitor 1. Log Only. 11:15:16 An EAS Participant has issued a Required Weekly Test for all of the United States and Washington, DC beginning at 11:15 am Tue Oct 2 and ending at 11:30 am Tue Oct 2 (NPR 1) Received 10/03/18 Required Weekly Test, Matched filter RWT, Received on Monitor 3. Log Only. 11:05:53 The National Weather Service has issued a Required Weekly Test for Scotts Bluf f, NE, Albany, WY, Sioux, NE, Platte, WY, Laramie, WY, Goshen, WY, Niobrara, WY, Kimball, NE, Northwest Laramie, WY, Converse, WY, North Laramie, WY, and Carbon, WY beginning at 11:05 am Wed Oct 3 and ending at 5:05 pm Wed Oct 3 (KCYS/NWS) Received 10/03/18 Matched filter NPT, Received from CAP. -

2010 Npr Annual Report About | 02

2010 NPR ANNUAL REPORT ABOUT | 02 NPR NEWS | 03 NPR PROGRAMS | 06 TABLE OF CONTENTS NPR MUSIC | 08 NPR DIGITAL MEDIA | 10 NPR AUDIENCE | 12 NPR FINANCIALS | 14 NPR CORPORATE TEAM | 16 NPR BOARD OF DIRECTORS | 17 NPR TRUSTEES | 18 NPR AWARDS | 19 NPR MEMBER STATIONS | 20 NPR CORPORATE SPONSORS | 25 ENDNOTES | 28 In a year of audience highs, new programming partnerships with NPR Member Stations, and extraordinary journalism, NPR held firm to the journalistic standards and excellence that have been hallmarks of the organization since our founding. It was a year of re-doubled focus on our primary goal: to be an essential news source and public service to the millions of individuals who make public radio part of their daily lives. We’ve learned from our challenges and remained firm in our commitment to fact-based journalism and cultural offerings that enrich our nation. We thank all those who make NPR possible. 2010 NPR ANNUAL REPORT | 02 NPR NEWS While covering the latest developments in each day’s news both at home and abroad, NPR News remained dedicated to delving deeply into the most crucial stories of the year. © NPR 2010 by John Poole The Grand Trunk Road is one of South Asia’s oldest and longest major roads. For centuries, it has linked the eastern and western regions of the Indian subcontinent, running from Bengal, across north India, into Peshawar, Pakistan. Horses, donkeys, and pedestrians compete with huge trucks, cars, motorcycles, rickshaws, and bicycles along the highway, a commercial route that is dotted with areas of activity right off the road: truck stops, farmer’s stands, bus stops, and all kinds of commercial activity. -

Fund Source As Of: 07/01/2021

University of Wyoming Chart of Accounts Values Segment: Fund Source As of: 07/01/2021 Unrestricted Operating Total Unrestricted Operating Summary 000001 Unrestricted Operating 000002 Unrest Op - Audit Only - Pension & OPEB Unrestricted Operating Reserve Summary 005001 Unrestricted Operating Reserve 005002 Non Capital Equipment Reserve 005003 Fringe Benefit Reserve 005004 Transportation Plane Reserve 005005 Bond Coverage Reserve 005006 Legal Reserve 005007 Voluntary Separation Incentive Plan 2017 Reserve Designated Operating Total Designated Operating General Summary 010002 Designated Operating General 010062 Designated Operating Transportation Plane 010069 Designated Operating Agriculture Experiment Station (AES) 010072 Designated Operating Board of Cooperative Educational Services (BOCES) 010077 Designated Operating Cepham Nair 010078 Designated Operating Cooperative Extension Services (CES) 010087 Designated Operating National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) 010093 Designated Operating Project Residuals 010104 Designated Operating Tier 1 010105 Designated Operating Veterans Certification 010107 Designated Operating WWAMI HB85 010108 Designated Operating WWAMI Repayment Fund 010109 Designated Operating WYDENT Repayment Fund 010120 Designated Operating WYDENT Tuition Contract Pmt HB85 Designated Operating Faculty Support Summary 050001 Designated Operating Faculty Start up 050002 Designated Operating Faculty Discretionary 050003 Designated Operating Faculty Development Designated Operating Funds from Fees Summary 070001 Designated -

FY 2016 and FY 2018

Corporation for Public Broadcasting Appropriation Request and Justification FY2016 and FY2018 Submitted to the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the House Appropriations Committee and the Labor, Health and Human Services, Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee of the Senate Appropriations Committee February 2, 2015 This document with links to relevant public broadcasting sites is available on our Web site at: www.cpb.org Table of Contents Financial Summary …………………………..........................................................1 Narrative Summary…………………………………………………………………2 Section I – CPB Fiscal Year 2018 Request .....……………………...……………. 4 Section II – Interconnection Fiscal Year 2016 Request.………...…...…..…..… . 24 Section III – CPB Fiscal Year 2016 Request for Ready To Learn ……...…...…..39 FY 2016 Proposed Appropriations Language……………………….. 42 Appendix A – Inspector General Budget………………………..……..…………43 Appendix B – CPB Appropriations History …………………...………………....44 Appendix C – Formula for Allocating CPB’s Federal Appropriation………….....46 Appendix D – CPB Support for Rural Stations …………………………………. 47 Appendix E – Legislative History of CPB’s Advance Appropriation ………..…. 49 Appendix F – Public Broadcasting’s Interconnection Funding History ….…..…. 51 Appendix G – Ready to Learn Research and Evaluation Studies ……………….. 53 Appendix H – Excerpt from the Report on Alternative Sources of Funding for Public Broadcasting Stations ……………………………………………….…… 58 Appendix I – State Profiles…...………………………………………….….…… 87 Appendix J – The President’s FY 2016 Budget Request...…...…………………131 0 FINANCIAL SUMMARY OF THE CORPORATION FOR PUBLIC BROADCASTING’S (CPB) BUDGET REQUESTS FOR FISCAL YEAR 2016/2018 FY 2018 CPB Funding The Corporation for Public Broadcasting requests a $445 million advance appropriation for Fiscal Year (FY) 2018. This is level funding compared to the amount provided by Congress for both FY 2016 and FY 2017, and is the amount requested by the Administration for FY 2018. -

General Manager's Newsletter | August 2021

General Manager's Newsletter | August 2021 WPM bids farewell to a dear friend and mourns the passing of Wyoming’s beloved U.S. Senator Mike Enzi. Senator Enzi was a champion for Wyoming, and a champion for her public media. He recorded a wonderful testimonial for Wyoming Public Media, which we often aired throughout the years. Truth be told, Mike Enzi wasn’t always enamored of everything he found on our airwaves, and occasionally I heard about it. But he was very astute to differentiate between the public and community service Wyoming Public Media provides directly to Wyomingites, and the product of national providers like NPR and American Public Media which serve broader national publics. He liked those strong Wyoming connections and sentiments! We will truly miss him and his quiet, sensible and pragmatic leadership. WPM staff will dedicate the broadcast day on August 6 to Senator Enzi’s memory. Here and Now welcomes a new host. Scott Tong starts Monday August 9, while WPM alum Peter O’Dowd returns to his role as senior editor. Scott logged 16 years at Marketplace. He was the China bureau chief in Shanghai from 2006 until 2010. Since then, he’s been a senior correspondent and has reported from more than a dozen countries — from refugee camps in East Africa to shoe factories in eastern China. As part of Marketplace’s Sustainability desk he has covered the global economy, energy and the environment — and done stories on everything from hacking and fracking, to climate and water, Hollywood in China, Huawei, driverless cars and tech spying. -

Professional-Broadca

ROFESSIONAL BROADCASTING' A HA FE INTLIDIDUCTICSI JOHN R.BITTNER Urofessional rroalcasting: a Uric' introduction JOHN R. BITTNER The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill PRENTICE-HALL, INC. Englewood Cliffs, N.J. 07632 Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Bittner, John R 1943- Professional broadcasting. Includes index. I. Broadcasting. I. Title. PNI990.8.B54 384.54 80-16152 ISBN 0-13-725465-2 ©1981 by Prentice-Hall, Inc., Englewood Cliffs, N.J. 07632 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 Editorial production/supervision and interior design by Barbara Kelly Cover design by Jorge Hernandez Manufacturing Buyer: Edmund W. Leone Prentice-Hall International, Inc., London Prentice-Hall of Australia Pty. Limited, Sydney Prentice-Hall of Canada, Ltd., Toronto Prentice-Hall of India Private Limited, New Delhi Prentice-Hall of Japan, Inc., Tokyo Prentice-Hall of Southeast Asia Pte. Ltd., Singapore Whitehall Books Limited, Wellington, New Zealand for Donald a very special son Contents Reface xiii Acknowledgments xiv Introduction xv 1 RADIO PREVIEW 1 STATION DIVERSITY 2 Personnel 2 Equipment 2 CHARACTERISTICS OF RADIO 3 Early programming concepts 3 Becoming specialized 4 Toward portability 7 The transistor 7 LOOKING BACK: THE BEGINNINGS OF RADIO 7 Marconi: the person 8 Marconi: the experimenter 9 The transatlantic broadcast 10 Developments in tube and circuit design 12 Voice -

Wyoming Public Media Report 2018

Wyoming Public Media Independent Auditor’s Report and Financial Statements June 30, 2018 and 2017 Wyoming Public Media June 30, 2018 and 2017 Independent Auditor’s Report ............................................................................................... 1 Management’s Discussion and Analysis………………………………………………………..3 Financial Statements Statements of Net Position ............................................................................................................... 10 Statements of Revenues, Expenses and Changes in Net Position .................................................... 12 Statements of Cash Flows ................................................................................................................ 13 Notes to Financial Statements .......................................................................................................... 15 Independent Auditor’s Report Board of Trustees University of Wyoming Wyoming Public Media Laramie, Wyoming We have audited the accompanying financial statements of Wyoming Public Media (the Network), a public media entity licensed to the Trustees of the University of Wyoming, reported as a part of the University of Wyoming, as of and for the year ended June 30, 2018, and the related notes to the financial statements, which collectively comprise the Network’s basic financial statements as listed in the table of contents. Management’s Responsibility for the Financial Statements Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of these financial -

James D. King

James D. King School of Politics, Public Affairs, & International Studies University of Wyoming Laramie, WY 82071 Telephone: 307-766-6239 Email: [email protected] Education Ph.D., Political Science, University of Missouri, 1983 M.A., Political Science, Western Michigan University, 1977 B.A., Social Science Teaching, Michigan State University, 1974 Academic Experience University of Wyoming, School of Politics, Public Affairs, & International Studies Professor of Political Science, 2017-present University of Wyoming, Department of Political Science Professor, 1999-2017 Department Head, 2007-2013, 2001-2004 Associate Professor, 1994-1999 Assistant Professor, 1992-1994 University of Memphis, Department of Political Science Associate Professor, 1986-1992 Department Chair, 1987-1990 Assistant Professor/Instructor, 1981-1986 Publications King, James D. In press. “Explaining and Predicting Midterm Congressional Election Outcomes: Factoring in Opposition Party Strategy.” The Forum: A Journal of Applied Research in Contemporary Politics. King, James D. In press. “Bill Clinton, Republican Strategy, and the 1994 Elections: How a Midterm Election Became a Referendum on the President.” American Review of Politics. 1 King, James D., Andrew Garner, Jason B. McConnell, and Robert A. Schuhmann. 2020. The Equality State: Government and Politics in Wyoming 9th ed. Plymouth, MI: Hayden- McNeil (earlier editions published in 2017, 2011, 2008, 2004, 2000, 1996). King, James D., and James W. Riddlesperger, Jr. 2018. “The Trump Transition: Beginning a Distinctive Presidency.” Social Science Quarterly 99 (November): 1821-1836. King, James D. 2018. “Party Rules and Equitable Representation in U.S. Presidential Nominating Contests.” American Politics Research 46 (September): 811-833. King, James D., and James W. Riddlesperger, Jr. 2017. “The 2016-2017 Transition into the Donald J. -

Merry Christmas! Visit Us At

VHF-UHF DIGEST The Official Publication of the Worldwide TV-FM DX Association DECEMBER 2010 The Magazine for TV and FM DXers FLEA MARKET FIND Andria Radio “Sharp Focus” Television/Radio The AUVIO HD TUNER IS IT ANY GOOD? Merry Christmas! Visit Us At www.wtfda.org THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION Serving the UHF-VHF Enthusiast THE VHF-UHF DIGEST IS THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE WORLDWIDE TV-FM DX ASSOCIATION DEDICATED TO THE OBSERVATION AND STUDY OF THE PROPAGATION OF LONG DISTANCE TELEVISION AND FM BROADCASTING SIGNALS AT VHF AND UHF. WTFDA IS GOVERNED BY A BOARD OF DIRECTORS: DOUG SMITH, GREG CONIGLIO, BRUCE HALL, KEITH McGINNIS AND MIKE BUGAJ. Editor and publisher: Mike Bugaj Treasurer: Keith McGinnis wtfda.org Webmaster: Tim McVey wtfda.info Site Administrator: Chris Cervantez Editorial Staff: Jeff Kruszka, Keith McGinnis, Fred Nordquist, Nick Langan, Doug Smith, Peter Baskind, Bill Hale and John Zondlo, Our website: www.wtfda.org; Our forums: www.wtfda.info DECEMBER 2010 _______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS Page Two 2 Mailbox 3 Finally! For those of you online with an email TV News…Doug Smith 4 address, we now offer a quick, convenient and FM News…Bill Hale 9 secure way to join or renew your membership FCC Facilities Changes 13 in the WTFDA. Just logon to Paypal and send Photo News…Jeff Kruszka 16 your dues to [email protected]. Northern FM DX…Keith McGinnis 19 Use the email address above to either join Southern FM DX…John Zondlo 25 the WTFDA or renew your membership in Coast to Coast TV DX…Nick Langan 26 North America’s only TV and DX organization. -

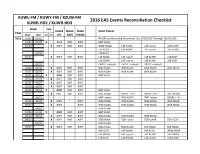

2016 EAS Events Reconciliation Checklist

KUWL-FM / KUWY-FM / KZUW-FM 2016 EAS Events Reconciliation Checklist KUWR-HD2 / KUWR-HD3 Week Sent KUWR NOAA FEMA Other Events Year Start End RMT RWT LP1 NWS IPAWS 2016 01/01 01/02 No EAS activity during this period. See 2015/12/27 through 2015/12/31. 01/03 01/09 X RMT RWT RWT RWT KCGY 01/10 X RWT RWT RWT WSW NOAA LAE NOAA LAE <sent> LAE KUWR LAE KCGY LAE NOAA LAE <sent> LAE KUWR 01/16 LAE KCGY 01/17 X RWT RWT RWT LAE NOAA LAE <sent> LAE KUWR LAE KCGY LAE NOAA LAE <sent> LAE KUWR LAE KCGY 01/23 ENDEC <reboot> ENDEC <reboot> ENDEC <reboot> 01/24 01/30 X RWT RWT RWT WSA NOAA WSA NOAA WSA NOAA WSA NOAA 01/31 02/06 X RWT RWT RWT WSA NOAA WSA NOAA WSA NOAA 02/07 02/13 X RMT RWT RWT RWT KCGY 02/14 02/20 X RWT RWT RWT 02/21 02/27 X RWT RWT RWT 02/28 03/05 X RWT RWT RWT 03/06 03/12 X RMT RWT RWT RWT KCGY 03/13 X RWT RWT RWT RWT NOAA ENDEC <*2> ENDEC <*2> RWT KUWR 03/19 RWT <sent> WSA NOAA RWT <sent> ENDEC <*2> 03/20 03/26 X RWT * RWT WSA NOAA WSA NOAA WSA NOAA WSA NOAA 03/27 X RWT RWT WSA NOAA WSA NOAA WSA NOAA WSA NOAA 04/02 WSA NOAA 04/03 04/09 X RMT RWT RWT RWT KCGY 04/10 04/16 X RWT RWT RWT WSA NOAA WSA NOAA WSA NOAA 04/17 X RWT RWT RWT TOR NOAA TOR <sent> TOR KUWR TOR KCGY 04/23 WSA NOAA 04/24 X RWT RWT RWT WSA NOAA WSA NOAA SVR NOAA SVR NOAA SVR KCGY SVR NOAA SVR KCGY WSW NOAA LAE IPAWS LAE <sent> LAE KUWR LAE IPAWS LAE KCGY LAE IPAWS LAE <sent> LAE KUWR LAE IPAWS LAE KCGY LAE KCGYKCGY WSA NOAA 04/30 WSA NOAA WSA NOAA 05/01 X RMT RWT RWT ENDEC <reboot> RWT KCGY FFW NOAA FFW KCGY SVR NOAA SVR KCGY SVA NOAA SVR NOAA FLW NOAA FLW KCGY FLW -

Wyoming Public Media

WYOMING PUBLIC MEDIA FINANCIAL REPORT JUNE 30, 2016 CONTENTS INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S REPORT 1 and 2 MANAGEMENT’S DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS (Required Supplementary Information) 3 - 8 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Statements of Net Position 9 Statements of Revenues, Expenses, and Changes in Net Position 10 Statements of Cash Flows 11 Notes to Financial Statements 12 - 27 REQUIRED SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION Schedule of OPEB Funding Progress 28 Schedule of the Station’s Proportionate Share of the Net Pension Liability 29 Schedule of the Station’s Contributions 30 Notes to Required Supplementary Information 31 INDEPENDENT AUDITOR’S REPORT To the Board of Trustees University of Wyoming Wyoming Public Media Laramie, Wyoming Report on the Financial Statements We have audited the accompanying financial statements of Wyoming Public Media (the “Station”), a component unit of the University of Wyoming, as of and for the years ended June 30, 2016 and 2015, and the related notes to the financial statements, which collectively comprise the Station’s basic financial statements as listed in the table of contents. Management’s Responsibility for the Financial Statements Management is responsible for the preparation and fair presentation of these financial statements in accordance with accounting principles generally accepted in the United States of America; this includes the design, implementation, and maintenance of internal control relevant to the preparation and fair presentation of financial statements that are free from material misstatement, whether due to fraud or error. Auditor’s Responsibility Our responsibility is to express an opinion on these financial statements based on our audits. We conducted our audits in accordance with auditing standards generally accepted in the United States of America. -

Office of the Governor

two thousand sixteen nomination information • Submission deadline october 3, 2016 MATTHEW H. MEAD STATE CAPITOL GOVERNOR THE STATE OF WYOMING CHEYENNE, WY 82002 Office of the Governor Established in 1982, the Governor’s Arts Awards recognize excellence in the arts and outstanding service to the arts in Wyoming. These awards were first made possible by an endowment from the Union Pacific Foundation in honor of Mrs. John U. Loomis, a lifelong patron of the arts. Over the years, individuals and organizations from more than 20 Wyoming communities and statewide organizations have been honored for their dedication to the arts in Wyoming. please include only the following: Any Wyoming citizen, organization, business or community may • One nomination letter: no more than 2 pages, single-spaced, #11 be a Governor’s Art Awards (GAA) nominee. Accomplishments font minimum and addressing the criteria outlined in this document that are noted should reflect substantial contributions made in • A minimum of two additional letters of recommendation, 1-2 Wyoming that exemplify a long-term commitment to the arts. pages each, single-spaced, #11 font minimum, supporting the Special consideration will be given to nominees whose arts nomination, and addressing the criteria in this document. It is service is statewide. recommended that these be from people who are familiar with differing aspects of the nominee’s arts involvement. Letters should Previous GAA recipients are not eligible for nomination, focus on contributions to the arts, and not other aspects of the but nomination of previously unselected nominees is nominee’s service to the community. encouraged. Current Wyoming Arts Council board members, • Resume of individual or history of organization or community, which staff members, contractors or members of their families are clearly demonstrates arts contributions not eligible for nomination.