20 May 2020 HOW ARTISTS TEACH LEADERSHIP: EIGHT PORTRAITS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pat Metheny: in Tune with the Big Picture

THE AUSTRALIAN ___________________________________________________________________________ Pat Metheny: In tune with the big picture Jazz guitarist and composer Pat Metheny performing in Rome, Italy, in July 2018. PICTURE GETTY IMAGES ERIC MYERS at Metheny, a youthful 65-year-old, began playing professional gigs as a teenage prodigy in the 1970s. Extraordinarily successful over 50 years, P the American guitarist has won so many polls, released so many gold albums, and been awarded so many Grammys (more than 20) that his fans have lost count, not to mention the honorary doctorates. Metheny is unique in that, as much as any jazz musician alive — along with pianist Keith Jarrett — he combines artistic acceptance (by hardcore jazz fans) and popularity (with music lovers otherwise uninterested in jazz). In a recent interview, Metheny dismisses what he describes as “all the subsets of the way music often gets talked about”. That is to say, the words often used to describe music don’t particularly interest him. “I am interested in the spirit and 1 sound of music itself,” he says. Accordingly, his thoughts are deeply philosophical. “To me, music is one big universal thing,” he tells The Australian. “The musicians I have admired the most are the ones who have a deep reservoir of knowledge and insight, not just about music, but about life in general, and are able to illuminate the things that they love in sound. “When it is a musician who can do that on the spot, as an improviser, that is usually my favourite kind of player.” So it is with the members of Metheny’s quartet, touring in Australia this week. -

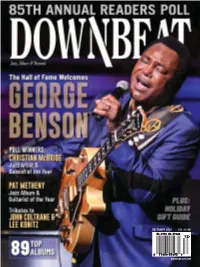

Downbeat.Com December 2020 U.K. £6.99

DECEMBER 2020 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM DECEMBER 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

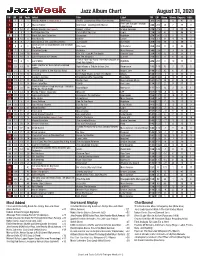

August 31, 2020 Jazz Album Chart

Jazz Album Chart August 31, 2020 TW LW 2W Peak Artist Title Label TW LW Move Weeks Reports Adds 1 1 1 1 Antonio Adolfo 4 weeks at No. 1 BruMa: Celebrating Milton Nascimento AAM Music 303 298 5 8 47 0 The Funk Garage / Mascot 2 4 2 2 Maceo Parker Soul Food - Cooking With Maceo Label Group 286 260 26 7 45 0 3 3 13 3 Bobby Watson Most Reports Keepin’ It Real Smoke Sessions 279 278 1 4 53 7 3 7 4 3 Jeff Hamilton Trio Catch Me If You Can Capri 279 238 41 7 48 4 5 2 7 2 Black Art Jazz Collective Ascension HighNote 274 296 -22 5 52 3 6 6 18 6 Ray Mantilla Rebirth Savant 272 251 21 4 46 2 7 9 9 7 Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers Just Coolin’ Blue Note 269 230 39 4 49 4 Dave Stryker w/ Bob Mintzer and the WDR 7 5 5 1 Big Band Blue Soul Strikezone 269 258 11 9 46 0 9 7 3 3 Christian Sands Be Water Mack Avenue 245 238 7 9 44 1 10 11 14 10 Various Ella 100 - Live At The Apollo Concord Jazz 224 192 32 8 26 1 11 13 10 9 John Fedchock NY Sextet Into The Shadows Summit 214 187 27 6 44 3 12 10 6 1 Larry Willis I Fall in Love Too Easily The Final Session at HighNote 202 201 1 10 37 0 Rudy Van Gelder’s Eddie Daniels w/ Dave Grusin and Bob 13 28 49 13 James Night Kisses a Tribute to Ivan Lins Resonance 192 149 43 3 37 5 14 31 37 14 Derrick Gardner & the Big dig! Band Still I Rise Impact Jazz 190 145 45 6 37 2 15 14 15 11 La Lucha Everybody Wants To Rule The World Arbors 184 186 -2 8 32 0 16 12 11 3 Kandace Springs The Women Who Raised Me Blue Note 182 190 -8 19 35 1 17 19 17 17 Steve Fidyk Battle Lines Blue Canteen Music 181 167 14 8 36 0 18 22 15 9 Alexa -

Wilderness & Land Ethic Curriculum

the WILDERNESS & LAND ETHIC CURRICULUM KINDERGARTEN THROUGH 8TH GRADE SECOND EDITION Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Contributor: PrimarycreditforinformationfoundinthispublicationgoestoMaryBethHennessy,PikeSan IsabelNationalForest;DavidCockrell,UniversityofSouthernColorado;LindaMarr,Vashon PublicSchools;andKariGunderson,Gunderson/FloodWildernessPartnerships.Othercon- tributorsincludeMicheleVanHare,ArapahoeRooseveltNationalForest;SharonKyhl,Pike SanIsabelNationalForest;SallyBlevinsandRebeccaCothran,BitterrootNationalForest;Joy JolsonandLisaTherill,WenatcheeNationalForest;JeanneMoeandKellyLetts,Bureauof LandManagement;andCliffordKnapp,NorthernIllinoisUniversity.MaryBethHennessy deservesspecialrecognitionfordevelopingcurriculum,conductingteacherworkshopsandfor herenthusiasmanddedicationtowildernesseducation.DavidCockrellandKariGunderson arelikewiseacknowledgedfortheirdedicationtothisproject.LindaMarrcontributedher expertiseasanelementaryteacherandspentcountlesshoursonthisproject.Manyteachersin Colorado,ForestServicewildernessmanagersandinterestedorganizationshavebeeninvolved inpilottestingthiscurriculum,revisions,andteacherworkshops.MarshaKearneyandLance TylerofthePikeSanIsabelNationalForestdeservespecialrecognitionfortheirsupportand enthusiasmforthisproject.ContributingrepresentativesfromTheWildernessEducation CouncilofColorado,WildernessEducationAssociation,ColoradoOutwardBoundSchool, WetlandsandWildlifeAlaskaCurriculum,NationalWildlifeFederation,ProjectWild,Project LearningTree,NaturalResourceConservationEducationandtheWildernessEducationWork- -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

THE COLLECTED POEMS of HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam

1 THE COLLECTED POEMS OF HENRIK IBSEN Translated by John Northam 2 PREFACE With the exception of a relatively small number of pieces, Ibsen’s copious output as a poet has been little regarded, even in Norway. The English-reading public has been denied access to the whole corpus. That is regrettable, because in it can be traced interesting developments, in style, material and ideas related to the later prose works, and there are several poems, witty, moving, thought provoking, that are attractive in their own right. The earliest poems, written in Grimstad, where Ibsen worked as an assistant to the local apothecary, are what one would expect of a novice. Resignation, Doubt and Hope, Moonlight Voyage on the Sea are, as their titles suggest, exercises in the conventional, introverted melancholy of the unrecognised young poet. Moonlight Mood, To the Star express a yearning for the typically ethereal, unattainable beloved. In The Giant Oak and To Hungary Ibsen exhorts Norway and Hungary to resist the actual and immediate threat of Prussian aggression, but does so in the entirely conventional imagery of the heroic Viking past. From early on, however, signs begin to appear of a more personal and immediate engagement with real life. There is, for instance, a telling juxtaposition of two poems, each of them inspired by a female visitation. It is Over is undeviatingly an exercise in romantic glamour: the poet, wandering by moonlight mid the ruins of a great palace, is visited by the wraith of the noble lady once its occupant; whereupon the ruins are restored to their old splendour. -

Exemplar Texts for Grades

COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS FOR English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects _____ Appendix B: Text Exemplars and Sample Performance Tasks OREGON COMMON CORE STATE STANDARDS FOR English Language Arts & Literacy in History/Social Studies, Science, and Technical Subjects Exemplars of Reading Text Complexity, Quality, and Range & Sample Performance Tasks Related to Core Standards Selecting Text Exemplars The following text samples primarily serve to exemplify the level of complexity and quality that the Standards require all students in a given grade band to engage with. Additionally, they are suggestive of the breadth of texts that students should encounter in the text types required by the Standards. The choices should serve as useful guideposts in helping educators select texts of similar complexity, quality, and range for their own classrooms. They expressly do not represent a partial or complete reading list. The process of text selection was guided by the following criteria: Complexity. Appendix A describes in detail a three-part model of measuring text complexity based on qualitative and quantitative indices of inherent text difficulty balanced with educators’ professional judgment in matching readers and texts in light of particular tasks. In selecting texts to serve as exemplars, the work group began by soliciting contributions from teachers, educational leaders, and researchers who have experience working with students in the grades for which the texts have been selected. These contributors were asked to recommend texts that they or their colleagues have used successfully with students in a given grade band. The work group made final selections based in part on whether qualitative and quantitative measures indicated that the recommended texts were of sufficient complexity for the grade band. -

Connections T H E N E W S L E T T E R O F M U S I C F O R P E O P L E: Fall 2016

CoNNeCTioNS T h e N e w s l e t t e r o f M u s i c f o r P e o p l e: Fall 2016 30th Anniversary, October, 2016 CELEBRATING 30 YEARS OF MUSIC MAKING!! IN THIS ISSUE: • Page 2: David Darling - Gratitude • Page 2 : 30 for 30 Fundraising Campaign • Page 3-7: Jan Hittle - MFP Celebrates 30 Years: Interviews with Participants at the 30th Anniversary Celebration • Page 8-10 : David Rudge - Mindfulness Through Music • Page 11: Mary Knysh- Letter from the MLP Chair: The Art of Imrpovisation 2016 • Page 12-14: Jan Hittle - We Turned 30! Highlights from the 30th Anniversary Workshop Weekend • Page 15-16: Jim Oshinsky - Kudos to David Darling • Page 16: Carol Purdy - Book Review: Steal Like and Artist by Austin Kleon • Page 17: Congratulations to our MLP Graduates- Alison Weiner and Alina Plourde • Page 18-19: MUSICAL Advertisements • Page 20: Jane Buttars - Improvised Music Harvest Workshop, 2016 • Page 21: Lynn Saltiel - News from Lynn Saltiel and the MFP Improv Orchestra • Page 22: Mary Knysh - Book Reveiw: The Fear of Singing Breakthrough Program: Learn to Sing Even if You Can’t Carry a Tune, by Nancy Salwen • Page 23: Calendar of Events and Who We Are; Advertise! Page 1 Gratitude From David Darling Dear MFP Community, I wanted to send all of you my love and gratitude. Your support is a blessing. I felt so overjoyed and grateful to celebrate our community at our 30th Anniversary Celebration this past October. Thank You to the staff and the breakout and elective leaders for their tremendous skills in organizing and presenting at our anniversary event. -

Leggi La Recensione Del Buscadero

J KANDACE SPRINGS (e pianista), protegèe di Prince dace sono, per sua stessa ammis- sta Steve Cardenas (collaborato- A THE WOMEN WHO RAISED ME (il defunto Monarca di Minnea- sione, Ella Fitzgerald, Sade ed Eva re di Norah Jones), il contrabbas- Z BLUE NOTE polis), che l’aveva molto convin- Cassidy. Ma in lei le anime sono sista Scott Colley (che ha trascorsi Z wwww to. E mi suggerì l’ascolto dell’al- molte di più. E con questo The con Carmen McRae) ed il batteri- bum Indigo (Blue Note, 2018). Women Who Raised Me lo sve- sta Clarence Penn (in passato si- Così ho conosciuto Kandace la pienamente rendendo dovu- deman di Diana Krall). In più uno Springs, ragazzotta sensualis- to tributo, come da esplicito ti- stuolo di ospiti che via via vedre- sima (dalle irresistibili lentiggi- tolo, a tutte le figure femminili mo. Dodici brani per dodici regi- ni) che riesce a combinare una che l’hanno influenzata decre- ne del canto e dell’espressività. Si voce alquanto personale al pa- tandone la splendida evoluzio- inizia con un tributo a Diana Krall, trimonio soul (old e new school) ne artistica. È ancora la Blue Devil May Care, dove il contrab- con accenti jazz aggiornatissimi Note a pubblicare. E qui un plau- basso di Christian McBride fa le- e mai banali, forte anche della so sentito va a Don Was che sta vitare letteralmente il brano. Su- produzione di un batterista at- cercando di far divenire la sto- bito dopo si celebra, in sequenza, tento e saggio come Karriem rica etichetta di Alfred Lion uno la grandezza di Ella Fitzgerald con Riggins. -

Deanna Witkowski Trio

presents the Deanna Witkowski Trio in concert featuring Deanna Witkowski, piano, voice Daniel Foose, bass Scott Latzky, drums Houghton College Recital Hall, Center for the Arts Tuesday, March 20th, 2018 7:00 PM Program This evening’s program will be selected from the following: (all works are arranged by Deanna Witkowski) For the Rest of My Life D. Witkowski From This Place Here with You A Rare Appearance Wide Open Window Hyfrydol traditional Lasst uns Erfreuen traditional Just One of Those Things Cole Porter (1891-1964) Let My Prayer Arise Text taken from Psalm 141 Music by D. Witkowski Lord, I Want to be a Christian traditional Love Came Down Text by Christina Rossetti Nocturne in B major, Op. 9, No. 3 Frédéric Chopin (1810-1849) Pass Me Not Text by Fanny Crosby Music by D. Witkowski Prelude in E minor, Op. 28, No. 4 F. Chopin with Insensatez Antonio Carlos Jobim As a courtesy to the performers and your fellow audience members, please be certain that all cell phones, watch alarms, and pagers are either turned off or set for silent operation. Flash photography can be very disconcerting to performers and is not permitted during the performance. Thank you for your cooperation. Deanna Witkowski, pianist, composer, vocalist Winner of the Great American Jazz Piano Competition and a past guest on Marian McPartland's Piano Jazz, New York City based pianist, composer and arranger Deanna Witkowski has been heralded for her “consistently thrilling” playing and her “boundless imagination” (All Music Guide). Her new trio album, Makes the Heart to Sing: Jazz Hymns, features twelve of her congregational jazz hymn arrangements along with a companion sheet music book. -

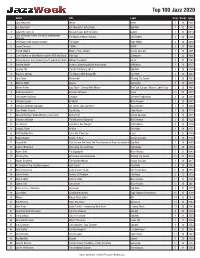

Top 100 Jazz 2020

Top 100 Jazz 2020 Artist Title Label Peak Weeks Spins 1 Joey Alexander Warna Verve 1 30 6300 2 Eric Alexander Eric Alexander with Strings HighNote 1 32 5957 3 Lafayette Harris Jr. You Can’t Lose with the Blues Savant 1 32 5914 Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra with Wynton 4 Marsalis The Music of Wayne Shorter Blue Engine 2 32 5336 5 Jeff Rupert with George Garzone The Ripple Rupe Media 6 30 4838 5 Jason Tiemann T-MAN TMAN 2 31 4838 7 Harold Mabern Mabern Plays Mabern Smoke Sessions 1 26 4835 8 Dave Stryker w/ Bob Mintzer and the WDR Big Band Blue Soul Strikezone 1 25 4806 9 Kenny Barron | Dave Holland Trio ft. Johnathan Blake Without Deception Dare2 2 27 4782 10 Antonio Adolfo BruMa: Celebrating Milton Nascimento AAM Music 1 24 4737 11 Jeremy Pelt The Art of Intimacy, Vol. 1 HighNote 3 28 4704 12 Kandace Springs The Women Who Raised Me Blue Note 3 25 4642 13 John Stein Watershed Whaling City Sound 2 25 4502 14 Michael Wolff Bounce Sunnyside 5 29 4497 15 Maceo Parker Soul Food - Cooking With Maceo The Funk Garage / Mascot Label Group 2 23 4466 16 Andrea Brachfeld Brazilian Whispers Origin 10 33 4374 17 Christopher Hollyday Dialogue Jazzbeat Productions 4 33 4369 18 Christian Sands Be Water Mack Avenue 3 25 4357 19 Christian McBride Big Band For Jimmy, Wes and Oliver Mack Avenue 1 17 4335 20 Cory Weeds Quartet Day By Day Cellar Music 1 26 4310 21 Vincent Herring / Bobby Watson / Gary Bartz Bird at 100 Smoke Sessions 1 38 4267 22 Christian McBride The Movement Revisited Mack Avenue 2 33 4256 23 Jae Sinnett Just When You Thought J-Nett Music -

Final Nominations List

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF RECORDING ARTS & SCIENCES, INC. FINAL NOMINATIONS LIST THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF RECORDING ARTS & SCIENCES, INC. Final Nominations List 63rd Annual GRAMMY® Awards For recordings released during the Eligibility Year September 1, 2019 through August 31, 2020 Note: More or less than 5 nominations in a category is the result of ties. General Field Category 1 8. SAVAGE Record Of The Year Megan Thee Stallion Featuring Beyoncé Award to the Artist and to the Producer(s), Recording Engineer(s) Beyoncé & J. White Did It, producers; Stuart White, and/or Mixer(s) and mastering engineer(s), if other than the artist. engineer/mixer; Colin Leonard, mastering engineer 1. BLACK PARADE Beyoncé Beyoncé & Derek Dixie, producers; Stuart White, engineer/mixer; Colin Leonard, mastering engineer 2. COLORS Black Pumas Adrian Quesada, producer; Adrian Quesada, engineer/mixer; JJ Golden, mastering engineer 3. ROCKSTAR DaBaby Featuring Roddy Ricch SethinTheKitchen, producer; Derek "MixedByAli" Ali, Chris Dennis & Liz Robson, engineers/mixers; Susan Tabor, mastering engineer 4. SAY SO Doja Cat Tyson Trax, producer; Clint Gibbs, engineer/mixer; Mike Bozzi, mastering engineer 5. EVERYTHING I WANTED Billie Eilish Finneas O'Connell, producer; Rob Kinelski & Finneas O'Connell, engineers/mixers; John Greenham, mastering engineer 6. DON'T START NOW Dua Lipa Caroline Ailin & Ian Kirkpatrick, producers; Josh Gudwin, Drew Jurecka & Ian Kirkpatrick, engineers/mixers; Chris Gehringer, mastering engineer 7. CIRCLES Post Malone Louis Bell, Frank Dukes & Post Malone, producers; Louis Bell & Manny Marroquin, engineers/mixers; Mike Bozzi, mastering engineer © The Recording Academy 2020 - all rights reserved 1 Not for copy or distribution 63rd Finals - Press List General Field Category 2 8.