Ellis, Charlesetta M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

**************************W************************* Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made * * from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 315 684 CG 022 ',,63 AUTHOR Gerler, Edwin R., Jr., Ed.; Ciechalski, Joseph C., Ed; Parker, Larry D., Ed. TITLE Elementary School Counseling in a Changing World. INSTITUTION American School. Counselor Association. Alexandria, VA.; ERIC Clearinghouse on Counseling and Personnel Services, Ann Arbor, Mich. SPONS AGENCY Office of Educational Research and Improvement (Er , Washington, DC. REPORT NO ISBN 1-56109-000-X PUB DATE 90 CONTRACT RI88062011 NOTE 414p.; For individual chapters, see CG 022 264-273. AVAILABLE FROM ERIC/CAPS, 2108 School of Education, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1259 ($26.95 each). PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020) -- Information Analyses - ERIC Iniormation Analysis Products (071) -- Books (010) EDRS PRICE MFO1 /PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Behavior; Change; Child Abuse; Child Neglert; *Counseling Techniques; *Counselor Role; Cultural Differences; Drug Abuse; Elementary Education; *Elementary Schools; Employment; Exceptional Persons; Family Life; Human Relations; Learning Strategies; *School Counseling; *School Counselors; Technology ABSTRACT This book of readings was developed to increase the reader's awareness of the cultural and social issues which face children and their counselors. It draws attention to environmental factors which impinge on both teaching and counseling techniques, and encourages counselors to re-examine their roles and interventions for the 1990s. The readings show counselors in elementary schools how to help children grow and develop in a changing world. Each chapter of the book contains articles that have been published in counseling jourials during the 1980s. Each chapter begins with an introduction by the editors and concludes with a set of issues designed to stimulate thinking about the current state of elementary school counseling. -

Captain America and the Struggle of the Superhero This Page Intentionally Left Blank Captain America and the Struggle of the Superhero Critical Essays

Captain America and the Struggle of the Superhero This page intentionally left blank Captain America and the Struggle of the Superhero Critical Essays Edited by ROBERT G. WEINER Foreword by JOHN SHELTON LAWRENCE Afterword by J.M. DEMATTEIS McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London ALSO BY ROBERT G. WEINER Marvel Graphic Novels and Related Publications: An Annotated Guide to Comics, Prose Novels, Children’s Books, Articles, Criticism and Reference Works, 1965–2005 (McFarland, 2008) LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Captain America and the struggle of the superhero : critical essays / edited by Robert G. Weiner ; foreword by John Shelton Lawrence ; afterword by J.M. DeMatteis. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-3703-0 softcover : 50# alkaline paper ¡. America, Captain (Fictitious character) I. Weiner, Robert G., 1966– PN6728.C35C37 2009 741.5'973—dc22 2009000604 British Library cataloguing data are available ©2009 Robert G. Weiner. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover images ©2009 Shutterstock Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 6¡¡, Je›erson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Dedicated to My parents (thanks for your love, and for putting up with me), and Larry and Vicki Weiner (thanks for your love, and I wish you all the happiness in the world). JLF, TAG, DW, SCD, “Lizzie” F, C Joyce M, and AH (thanks for your friend- ship, and for being there). -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. August 3, 2020 to Sun. August 9, 2020

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. August 3, 2020 to Sun. August 9, 2020 Monday August 3, 2020 7:30 PM ET / 4:30 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Rock Legends TrunkFest with Eddie Trunk Cream - Fronted by Eric Clapton, Cream was the prototypical power trio, playing a mix of blues, Sturgis Motorycycle Rally - Eddie heads to South Dakota for the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally at the rock and psychedelia while focusing on chunky riffs and fiery guitar solos. In a mere three years, Buffalo Chip. Special guests George Thorogood and Jesse James Dupree join Eddie as he explores the band sold 15 million records, played to SRO crowds throughout the U.S. and Europe, and one of America’s largest gatherings of motorcycle enthusiasts. redefined the instrumentalist’s role in rock. 8:30 AM ET / 5:30 AM PT Premiere Rock & Roll Road Trip With Sammy Hagar 8:00 PM ET / 5:00 PM PT Mardi Gras - The “Red Rocker,” Sammy Hagar, heads to one of the biggest parties of the year, At Home and Social Mardi Gras. Join Sammy Hagar as he takes to the streets of New Orleans, checks out the Nuno Bettencourt & Friends - At Home and Social presents exclusive live performances, along world-famous floats, performs with Trombone Shorty, and hangs out with celebrity chef Emeril with intimate interviews, fun celebrity lifestyle pieces and insightful behind-the-scenes anec- Lagasse. dotes from our favorite music artists. 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT Premiere The Big Interview Special Edition 9:00 PM ET / 6:00 PM PT Keith Urban - Dan catches up with country music superstar Keith Urban on his “Ripcord” tour. -

William Witney Ùيلم قائمة (ÙÙŠÙ

William Witney ÙÙ ŠÙ„Ù… قائمة (ÙÙ ŠÙ„Ù… وغراÙÙ ŠØ§) Tarzan's Jungle Rebellion https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/tarzan%27s-jungle-rebellion-10378279/actors The Lone Ranger https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-lone-ranger-10381565/actors Trail of Robin Hood https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/trail-of-robin-hood-10514598/actors Twilight in the Sierras https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/twilight-in-the-sierras-10523903/actors Young and Wild https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/young-and-wild-14646225/actors South Pacific Trail https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/south-pacific-trail-15628967/actors Border Saddlemates https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/border-saddlemates-15629248/actors Old Oklahoma Plains https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/old-oklahoma-plains-15629665/actors Iron Mountain Trail https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/iron-mountain-trail-15631261/actors Old Overland Trail https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/old-overland-trail-15631742/actors Shadows of Tombstone https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/shadows-of-tombstone-15632301/actors Down Laredo Way https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/down-laredo-way-15632508/actors Stranger at My Door https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/stranger-at-my-door-15650958/actors Adventures of Captain Marvel https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/adventures-of-captain-marvel-1607114/actors The Last Musketeer https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-last-musketeer-16614372/actors The Golden Stallion https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-golden-stallion-17060642/actors Outlaws of Pine Ridge https://ar.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/outlaws-of-pine-ridge-20949926/actors The Adventures of Dr. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. September 21, 2020 to Sun. September 27, 2020

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. September 21, 2020 to Sun. September 27, 2020 Monday September 21, 2020 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT Plain Spoken: John Mellencamp TrunkFest with Eddie Trunk This stunning, cinematic concert film captures John with his full band, along with special guest Sturgis Motorycycle Rally - Eddie heads to South Dakota for the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally at the Carlene Carter, performing his most cherished songs. “Small Town,” “Minutes to Memories,” “Pop Buffalo Chip. Special guests George Thorogood and Jesse James Dupree join Eddie as he explores Singer,” “Longest Days,” “The Full Catastrophe,” “Rain on the Scarecrow,” “Paper in Fire,” “Authority one of America’s largest gatherings of motorcycle enthusiasts. Song,” “Pink Houses” and “Cherry Bomb” are some of the gems found on this spectacular concert film. 8:30 AM ET / 5:30 AM PT Rock & Roll Road Trip With Sammy Hagar 6:40 PM ET / 3:40 PM PT Livin’ Live - The season 2 Best of Rock and Roll Road Trip with Sammy Hagar brings you never- AXS TV Insider before-seen performances featuring Sammy and various season 2 guests. Featuring highlights and interviews with the biggest names in music. 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT 6:50 PM ET / 3:50 PM PT The Big Interview Cat Stevens: A Cat’s Attic Joan Baez - Dan Rather sits down with folk trailblazer and human rights activist Joan Baez to Filmed in London, “A Cat’s Attic” celebrates the illustrious career of one of the most important discuss her music, past loves, and recent decision to step away from the stage. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. June 29, 2020 to Sun. July 5, 2020 Monday

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. June 29, 2020 to Sun. July 5, 2020 Monday June 29, 2020 7:20 PM ET / 4:20 PM PT 8:00 AM ET / 5:00 AM PT AXS TV Insider Rock Legends Featuring highlights and interviews with the biggest names in music. Earth, Wind & Fire - Earth, Wind & Fire is an American band that has spanned the musical genres of R&B, soul, funk, jazz, disco, pop, rock, Latin and African. They are one of the most successful 7:30 PM ET / 4:30 PM PT bands of all time. Leading music critics cast fresh light on their career. Rock Legends Journey - Journey is an American rock band that formed in San Francisco in 1973, composed of 8:30 AM ET / 5:30 AM PT former members of Santana and Frumious Bandersnatch. The band has gone through several Rock & Roll Road Trip With Sammy Hagar phases; its strongest commercial success occurred between 1978 and 1987. Sunset Strip - Sammy heads to Sunset Blvd to reminisce at the Whisky A-Go-Go before visit- ing with former Mötley Crüe drummer Tommy Lee at his house. After cooking together and Premiere exchanging stories, the guys rock out in Tommy’s studio. 8:00 PM ET / 5:00 PM PT Nothing But Trailers 9:00 AM ET / 6:00 AM PT Sometimes the best part of the movie is the preview! Watch some of the best trailers, old and The Big Interview new, during this special presentation. Dwight Yoakam - Country music trailblazer takes time from his latest tour to discuss his career and how he made it big in the business far from Nashville. -

Celebrating Eighty Years of Public Higher Education in the Bronx

Lehman TODAY SPRING 2011 Celebrating Eighty Years of Public Higher Education in the Bronx The Courage to Step Forward The President’s Report, 2010 The Magazine of Lehman College For Alumni and Friends Spring 2011 • Vol. 4, No. 1 Contents Features The Courage to Step Forward 11 • Coming Out of the Shadows 12 • Making a Difference 14 • Speaking for the Victims 16 22 Of Injustice 11 Photo by Roy Wright • Stranded in Chile 19 Chronicles of the Pioneers of ‘31 20 Departments Celebrating Eighty Years of Public 22 2 Campus Walk Higher Education in the Bronx 5 Sports News Spotlight on Alumni 27-30 20 6 Bookshelf Marsha Ellis Jones (‘71), Douglas Henderson, Jr. (‘69), Mary Finnegan Cabezas (‘72), Angel Hernández (‘09), 8 Development News María Caba (‘95), and a Message from the Alumni 31 Alumni Notes Relations Director Plus: The President’s Report, 2011 35-40 27 On the Cover: The many lights and activities of the Music Building—one of the original campus buildings, known fi rst as Student Hall—symbolize the learning that has taken place here for eighty years. Photo by Jason Green. Lehman Today is produced by the Lehman College Offi ce of Media Relations and Publications, 250 Bedford Park Blvd. West, Bronx, NY 10468. Staff for this issue: Marge Rice, editor; Keisha-Gaye Anderson, Lisandra Merentis, Yeara Milton, Nancy Novick, Norma Strauss, Joseph Tirella, and Phyllis Yip. Freelance writer: Anne Perryman. Opinions expressed in this publication may not necessarily refl ect those of the Lehman College or City University of New York faculty and administration. -

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. August 3, 2020 to Sun. August 9, 2020 Monday August 3, 2020

AXS TV Canada Schedule for Mon. August 3, 2020 to Sun. August 9, 2020 Monday August 3, 2020 2:00 PM ET / 11:00 AM PT 6:00 AM ET / 3:00 AM PT Eric Clapton: The 1970s Review Tom Green Live Eric Clapton’s musical journey through the seventies is recalled, from his days with musical Sandra Bernhard - Seriously. Funny. Talk. The filters are off and all systems are a “Go” as actress/ collectives after Cream disbanded, to his hugely successful solo career, as told by musicians and comedian/singer/author Sandra Bernhard graces Tom Green Live! Talented, honest and brutally biographers who knew him best during that period. witty, she has counted Madonna and director Martin Scorsese among her admirers and col- laborators. 5:00 PM ET / 2:00 PM PT Cream - Live at Royal Albert Hall 7:00 AM ET / 4:00 AM PT In May of 2005, Cream returned to London’s Royal Albert Hall, to the same stage where they The Very VERY Best of the 70s had completed what was thought to be their final performance in 1968. It was one of the Disaster Movies - We’re ranking your favorite disaster movies of the 70s. From dramatic to most eagerly anticipated, hard-to-get tickets in rock history. This program documents Cream’s groundbreaking, these movies captivated audiences. Find out which disaster movies made our momentous London shows. Performances from each of the four nights are featured and much list as Morgan Fairchild, Michael Winslow, Anson Williams, Perez Hilton and more give us their more. -

Invaders Sample.Pdf

Mark McDermott 4937 Stanley Ave. Downers Grove, IL 60515 [email protected] These excerpts are intended as “writing samples” for the author of the articles presented. They are not intended for reuse or re-publication without the consent of the publisher or the copyright holder. ©2009 Robert G. Weiner. All rights reserved McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Mark McDermott 4937 Stanley Ave. Downers Grove, IL 60515 [email protected] The Invaders and the All-Star Squadron Roy Thomas Revisits the Golden Age Mark R. McDermott Introduction By the mid-1970’s, many fans of the “Golden Age” of comic books had grown up to become writers and ultimately editors for the comics publishers, sometimes setting the nar- rative histories for their favorite childhood characters themselves. Many of these fans-turned- pro produced comics series that attempted to recapture the Golden Age’s excitement, patriotic fervor and whiz-bang attitude. The most successful of these titles were produced by Roy Thomas, who fashioned a coherent history of costumed heroes during World War II, and rec- onciled the wildly inconsistent stories of the 1940’s with tightly patrolled continuity initiated with the “Silver Age” of the 1960’s. With The Invaders (1975-1979), Thomas focused on the hitherto unrevealed wartime exploits of Marvel Comics’ early mainstays Captain America, the Human Torch, and Prince Namor, the Sub-Mariner. In 1980, he moved to DC Comics and launched All-Star Squadron, which juggled the histories of the Justice Society of Amer- ica and nearly a hundred secondary characters. -

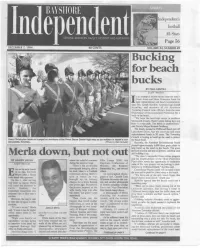

BAYSHORE Merla Down, but Not out Bucking for Beach Bucks

BAYSHORE Independent’s f o o t b a l l A l l - S t a r s SERVING ABERDEEN,HAZLET, KEYPORT AND MATAWAN Page 56 DECEMBER 7, 1994 40 CENTS VOLUME 24, NUMBER 49 Bucking for beach bucks BY PAUL GENTILE Staff Writer n an attempt to secure monies from the state’s Green Acres and Shore Protection funds for I sand replenishment and beach beautification, state Sen. Joseph Kyrillos, Assemblyman Joseph Azzolina, and members of the Aberdeen Township Council took officials from the state Department of Environmental Protection for a walk on the beach. “We have the best-kept secret in northern Monmouth County. There’s great fishing here and there is a nice park. The beach is underutilized,” said Deputy Mayor Richard Goldberg. The beach, located in Cliffwood Beach just off Lakeshore Drive, has not received any state replenishment funds in 20 years. The Township Council is hoping to build up the sand to protect Stacy Christopher leads on trumpet as members of the Perna Dance Center high step as toy soldiers in Hazlet’s holi the beach front. day parade, Saturday. (Photo by Rich Schultz) Recently, the Aberdeen Environmental Board planted approximately 6,000 dune grass plants to help build up the sand on the beach. The grass prevents erosion and acts as a fence, catching sand Merla down, but not out and building it up. “The state’s successful Green Acres program and the establishment of the Shore Protection BY LAUREN JAEGER ument the colorful moments Elks Lodge 2030, the Fund allow towns the opportunity to undertake during his mayoral reign. -

Rock & Roll's War Against

Rock & Roll’s War Against God Copyright 2015 by David W. Cloud ISBN 978-1-58318-183-6 Tis book is published for free distribution in eBook format. It is available in PDF, Mobi (for Kindle, etc.) and ePub formats from the Way of Life web site. See the Free eBook tab at www.wayofife.org. We do not allow distribution of our free books from other web sites. Published by Way of Life Literature PO Box 610368, Port Huron, MI 48061 866-295-4143 (toll free) - [email protected] www.wayofife.org Canada: Bethel Baptist Church 4212 Campbell St. N., London Ont. N6P 1A6 519-652-2619 Printed in Canada by Bethel Baptist Print Ministry ii Table of Contents Introduction ...........................................................................1 What Christians Should Know about Rock Music ...........5 What Rock Did For Me ......................................................38 Te History of Rock Music ................................................49 How Rock & Roll Took over Western Society ...............123 1950s Rock .........................................................................140 1960s Rock: Continuing the Revolution ........................193 Te Character of Rock & Roll .........................................347 Te Rhythm of Rock Music .............................................381 Rock Musicians as Mediums ...........................................387 Rock Music and Voodoo ..................................................394 Rock Music and Insanity ..................................................407 Rock Music and Suicide ...................................................429 -

Maskierte Helden

Aleta-Amirée von Holzen Maskierte Helden Zur Doppelidentität in Pulp-Novels und Superheldencomics Populäre Literaturen und Medien 13 Herausgegeben von Ingrid Tomkowiak Aleta-Amirée von Holzen Maskierte Helden Zur Doppelidentität in Pulp-Novels und Superheldencomics DiePubliziert Druckvorstufe mit Unterstützung dieser Publikation des Schweizerischen wurde vom Nationalfonds Schweizerischen Nationalfondszur Förderung derzur wissenschaftlichenFörderung der wissenschaftlichen Forschung. Forschung unterstützt. Die vorliegende Arbeit wurde von der Philosophischen Fakultät der Universität Zürich im Frühjahrssemester 2018 auf Antrag von Prof. Dr. Ingrid Tomkowiak und Prof. Dr. Klaus Müller-Wille als Dissertation angenommen. Weitere Informationen zum Verlagsprogramm: www.chronos-verlag.ch Umschlagbild: Steve Ditko (Zeichner), Stan Lee (Autor) et al.: «Unmasked by Dr. Octopus», in: Spider-Man Classics Vol. 1, No. 13, April 1994, S. 5 (Nachdruck aus: The Amazing Spider-Man 12, Mai 1964). © Marvel Comics © 2019 Chronos Verlag, Zürich Print: ISBN 978-3-0340-1508-0 E-Book (PDF): DOI 10.33057/chronos.1508 5 Inhalt Einleitung 7 Maskerade und Geheimnis 17 Verbergen und Zeigen – Enthüllung durch Verhüllung 18 Geheimnisbedrohung und -bewahrung: Narrative Koordinaten der Doppelidentität 30 Masken, Rollen, Identitäten 45 «Die ganze Welt ist eine Bühne» – die metaphorische Maske 49 Interaktion und Identität, Konformität und Einzigartigkeit 56 Interpretationsansätze zur Doppelidentität (der Mann aus Stahl und der unscheinbare Reporter) 67 Die zivile Identität