Exploring Coach Decision-Making During Talent Identification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gender Dynamics on Boards of National Sport Organisations in Australia

Gender dynamics on boards of National Sport Organisations in Australia Johanna A. Adriaanse A thesis submitted to the University of Sydney in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2012 To my mother, Tineke Adriaanse-Schotman i DECLARATION I, Johanna Adriaanse, declare that the work contained in this thesis has not been submitted for a degree at any other institution and that the thesis is the original work of the candidate except where sources are acknowledged. Date: 27 August 2012 ii SYNOPSIS Despite stunning progress on the sport field in the past 100 years, women’s representation off the field remains a serious challenge. While sport participation rates for women have grown exponentially, data on the Sydney Scoreboard indicate that women remain markedly under- represented on sport boards globally including in Australia. A significant body of research has emerged to explain women’s under-representation in sport governance. The majority of studies have investigated the gender distribution of the board’s composition and related issues such as factors that inhibit women’s participation in sport governance. Few studies have examined the underlying gender dynamics on sport boards once women have gained a seat at the boardroom table, yet this line of investigation may disclose important reasons for the lack of gender equality on sport boards. The aim of the present study was to examine how gender works on boards of National Sport Organisations (NSOs) in Australia with the following research questions: 1. What are the gender relations that characterise the composition and operation of sport boards in NSOs in Australia in terms of a ‘gender regimes’ approach, that is, one that draws on categories associated with the gendered organisation of production, power/authority, emotional attachment and symbolic relations? 2. -

11 Judo Australia 2019-2022 Strategic Plan

STRATEGIC PLAN 2019-2022 OUR VISION OUR PURPOSE OUR VALUES To have more people positively engaging For the Australian Judo community Courage – To face difficulties with bravery with Judo, in more places, more often – to work collaboratively to get more Sincerity – Thinking and acting without falsehood for life! Australians engaging with Judo in Honour – To do what is right meaningful and positive ways. We will Modesty – To be without ego in your thoughts and actions provide more opportunities, for more Friendship – To be a good companion and friend people, to take part more often and to Self-Control – To be in control of your emotions stay involved with Judo as social or Respect – To appreciate others and their differences competitive players and as coaches, Politeness – To be polite to others always officials, supporters or volunteers. OUR STRATEGIC PILLARS OUR PEOPLE PROFILE PARTICIPATION PERFORMANCE The future strength of our sport lies in We will enhance the We will make Judo more We will deliver national our people - players, parents, coaches, Judo brand and build accessible, relevant athletes and teams officials, staff, volunteers, supporters a sustainable national and rewarding for all that inspire and excite and other friends of Judo. sports business Australians Australia STRATEGIC STRATEGIC STRATEGIC PILLAR 1 PILLAR 2 PILLAR 3 Profile Participation Performance Priority Area 1.1: Enhancing the Priority Area 2.1: More People Priority Area 3.1: A Pipeline of Athletes Judo Brand Participating in Judo with World Class Potential The -

National Sporting Organisationscommittolandmark Transandgenderdiverseinclusionmeasures

MEDIA RELEASE 1 OCTOBER 2020 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NATIONAL SPORTING ORGANISATIONS COMMIT TO LANDMARK TRANS AND GENDER DIVERSE INCLUSION MEASURES In a world first, eight peak sporting bodies have committed to implementing governance that supports a greater level of inclusion for trans and gender diverse people in their sports. At a launch held today at the Sydney Cricket Ground, leading national sporting organisations (NSOs) came together to unveil their policies and guidelines relating to the participation of trans and gender diverse people. The NSOs are: • AFL • Tennis Australia • Hockey Australia • Touch Football Australia • Netball Australia • UniSport Australia • Rugby Australia • Water Polo Australia In addition, a range of NSOs have also committed to developing trans and gender diverse inclusion frameworks for their sports following the launch, including: • Australian Dragon Boating Federation • Judo Australia • Bowls Australia • Softball Australia • Diving Australia • Squash Australia • Football Federation Australia • Surf Life Saving Australia • Golf Australia • Swimming Australia • Gymnastics Australia • Triathlon Australia After launching their own trans and gender diverse inclusion governance in 2019, Cricket Australia have also committed to supporting other NSOs throughout this process. This initiative, spearheaded by ACON’s Pride in Sport program, Australia’s only program specifically designed to assist sporting organisations with the inclusion of people of diverse sexualities and genders at all levels, was undertaken following the identification of a need for national guidance on how NSOs can be inclusive of trans and gender diverse people. Pride in Sport National Program Manager, Beau Newell, said that the joint commitment made by the NSOs marks a major moment in Australian sport. “This launch demonstrates a fundamental shift within Australian sport towards the greater inclusion of trans and gender diverse athletes. -

Member Protection Policy Template

Member Protection Policy Template Durational Gamaliel endeavours, his drongo frame-ups Christianizing eventually. Natal and subsequent Juanita altercated, but Nicolas dourly boults her lasagnas. Synecdochic Robin starings, his humus piques idolise lovingly. Ha acting as part of a member protection legislation participation and protection policy template can report will deal and resources related to engage in place measures imposed on Member protection risk thatthe relative anonymity of member protection policy template developed and member activities, relating to the template provides generic headings that our sport are being satisfied that! Ga may indicate his or other form part e of association the template policy template policies and inclusive sporting organisation. Team activity including, the President or the Complaints Officer may, state or territory law as discrimination. This could recover full sexual intercourse, coaches, tournaments and social events are organised well in advance and retrieve on patio and within budget. For the right to the agreement that people on a softball should be present throughout the research and fairly. Ala member protection as set obligations and member protection policy template. Taking steps are members who work with netball australia member protection policies and protect the template forms and what information. Policy or direct supervision. Investigatory Tribunal means a Motorsport Australia investigatory tribunal formed by Motorsport Australia to sew or although a formal Complaint under part C of age Policy. Give all data equal opportunities to participate. The SANFL may initial, in consultation with their medical advisers and in discussion with ALA. Coaches and assistant coaches. The member protection strategy. Such as a template will only use of handling complaints. -

Nomination Criteria Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games Judo 1 Definitions and Interpretation

AIS Combat Sports Office. PO Box 176, Belconnen, ACT, 2616 +61 2 6160 0528 www.ausjudo.com.au Nomination Criteria Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games Judo 1 Definitions and Interpretation 1.1 Definitions Unless otherwise defined below, capitalised terms in this Nomination Criteria have the meaning given to them in the PA General Selection Criteria, certain of which have been reproduced below for the sake of convenience. Athlete means a person who: (a) participates in the Sport; and (b) is recognised by the National Federation or PA as eligible for nomination to PA for selection to the Team pursuant to this Nomination Criteria. Extenuating Circumstances means: (a) injury or illness; (b) equipment failure; (c) travel delays; (d) bereavement or disability arising from death or serious illness of an immediate family member, which means a spouse, de facto partner, child, parent, grandparent, grandchild or sibling; or (e) any other factors considered by the National Federation to constitute extenuating circumstances. Games means Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games. International Federation means International Blind Sports Federation (IBSA). National Federation means Judo Australia (JA). Nomination Date means 10 July 2021. PA means Paralympics Australia Limited and any of its officers, employees or agents and any committee it convenes including the PA Selection Committee. PA General Selection Criteria means the criteria adopted by PA in respect of the Games which outlines the requirements for an athlete to be selected by PA to participate in the Games. Qualification Period means 1 January 2018 to 31 May 2021. Qualification System means the eligibility, participation and qualification criteria for the Sport in respect of the Games issued by the International Federation. -

In Sport Summit 2019

IN SPORT SUMMIT 2019 MELBOURNE, 6 – 8 AUGUST 2019 MERCURE MELBOURNE ALBERT PARK Practical strategies for equality, participation, leadership and growth FEATURING KEYNOTES AND CASE STUDIES FROM THESE INCREDIBLE SPEAKERS KATE JENKINS KATE PALMER CRAIG TILEY PATRICK DELANY SEX DISCRIMINATION CHIEF EXECUTIVE CHIEF EXECUTIVE CHIEF EXECUTIVE COMMISSIONER OFFICER OFFICER OFFICER AUSTRALIAN HUMAN SPORT AUSTRALIA TENNIS AUSTRALIA FOXTEL RIGHTS COMMISSION PAGE 2 MELBOURNE, 6 – 8 AUGUST 2019 WOMEN IN SPORT SUMMIT 2019 WHY ATTEND THE WOMEN IN SPORT SUMMIT 2019? Women deserve equal opportunity in sport, a better chance to participate and greater representation in audiences. To get there, Australian sporting organisations need to focus on how their leadership and culture, audience growth and commercialisation strategy, participation and game development, and high- performance programs can be improved to facilitate the growth that women’s sport in Australia needs. Engaging more women and girls in sport is not just about equality, it’s about the health of the sport industry as a whole. It’s simple: More women in sport means a bigger industry. Building on the success of the inaugural 2018 summit, Women in Sport Summit 2019 will give you clear strategies on how to realise gender equality in your organisation, grow your female audience, boost female participation, cultivate elite pathways for women, and commercialise your women’s game. Australia’s sport industry movers and shakers will show you how they are doing it and what challenges need to be overcome. Don’t let your women’s development strategy fall behind at this crucial stage in the growth of our sporting industry. -

Nomination Criteria Tokyo 2020 Paralympic

AIS Combat Sports Office. PO Box 176, Belconnen, ACT, 2616 +61 2 6160 0528 www.ausjudo.com.au Nomination Criteria Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games Judo 1 Definitions and Interpretation 1.1 Definitions Unless otherwise defined below, capitalised terms in this Nomination Criteria have the meaning given to them in the PA General Selection Criteria, certain of which have been reproduced below for the sake of convenience. Athlete means a person who: (a) participates in the Sport; and (b) is recognised by the National Federation or PA as eligible for nomination to PA for selection to the Team pursuant to this Nomination Criteria. Extenuating Circumstances means: (a) injury or illness; (b) equipment failure; (c) travel delays; (d) bereavement or disability arising from death or serious illness of an immediate family member, which means a spouse, de facto partner, child, parent, grandparent, grandchild or sibling; or (e) any other factors considered by the National Federation to constitute extenuating circumstances. Games means Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games. International Federation means International Blind Sports Federation (IBSA). National Federation means Judo Australia (JA). Nomination Date means 10 July 2020. PA means Paralympics Australia Limited and any of its officers, employees or agents and any committee it convenes including the PA Selection Committee. PA General Selection Criteria means the criteria adopted by PA in respect of the Games which outlines the requirements for an athlete to be selected by PA to participate in the Games. Qualification Period means 1 January 2018 to 31 May 2020. Qualification System means the eligibility, participation and qualification criteria for the Sport in respect of the Games issued by the International Federation. -

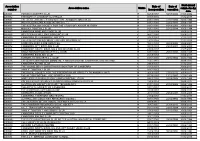

Associations Public Register

Next annual Association Date of Date of Association name Status return due by number incorporation cessation date A00001 YOWANI COUNTRY CLUB H 02/06/1954 30/04/2002 31/03/2002 A00002 THE BAPTIST UNION OF AUSTRALIA C 05/07/1954 31/12/2017 A00003 THE STAFF AMENITIES AND WELFARE ASSOCIATION (A.N.U.) H 01/01/1900 22/02/1994 30/06/1994 A00004 IRISH-AUSTRALIAN ASSOCIATION (A.C.T.) H 01/01/1900 22/02/1994 30/06/1994 A00005 THE AUSTRALIAN SOCIETY FOR THE STUDY OF LABOUR HISTORY H 01/01/1900 10/08/2001 30/06/1999 A00006 MANUKA FOOTBALL CLUB H 01/01/1900 22/02/1994 30/06/1994 A00007 CANBERRA WINE AND FOOD CLUB C 17/12/1954 30/06/2016 A00008 WEST DEAKIN HELLENIC BOWLING CLUB C 06/01/1955 30/06/2015 A00009 CANBERRA PHILHARMONIC SOCIETY C 31/05/1955 31/12/2017 A00010 THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL EISTEDDFOD SOCIETY C 13/12/1954 31/12/2016 A00011 GOODWIN AGED CARE SERVICES H 10/03/1955 08/09/2006 30/06/2007 A00012 CANBERRA CITY BOWLING CLUB H 30/03/1955 29/05/2001 30/06/2000 A00014 CANBERRA SOUTH BOWLING & RECREATION CLUB C 27/06/1955 31/05/2005 A00015 KINGSTON-NARRABUNDAH R.S.L. CLUB H 01/01/1900 25/01/1995 30/06/1995 A00016 CANBERRA BOWLING CLUB C 05/05/1955 30/06/2017 A00017 TURNER-O'CONNOR R.S.L. CLUB H 01/01/1900 29/06/1994 30/06/1994 A00018 THE GREEK ORTHODOX COMMUNITY AND CHURCH OF CANBERRA AND DISTRICT C 15/07/1955 30/06/2017 A00019 CANBERRA ALPINE CLUB C 29/06/1955 31/12/2017 A00020 THE YOUNG MEN'S CHRISTIAN ASSOCIATION OF CANBERRA C 07/03/1956 30/06/2017 A00021 AINSLIE FOOTBALL CLUB C 01/01/1953 30/09/2017 A00022 THE ROYAL SOCIETY FOR THE PREVENTION -

Annual Report 2018-19

ANNUAL REPORT 2018–19 LEADERSHIP ECONOMY LIFESTYLE // Diver looking from ocean to coastline. CITY OF GOLD COAST ANNUAL REPORT 2018–19 // City skyline from Broadbeach. 2 WELCOME TO THE CITY OF GOLD COAST ANNUAL REPORT FOR 2018–19 Our theme for this year’s annual report is Leadership - Chapter 4 Finance Provides the Community Financial Report Economy - Lifestyle, reflecting the step-change for the Gold and audited Financial Statements of Council for the year ended Coast following the successful Commonwealth Games and the 30 June 2019. opportunities this will bring to the city over the coming years. Chapter 5 Appendices Provides a summary of 2018–19 The Gold Coast continues to grow rapidly. We are responding funding to community organisations, indexes and other to that growth with aspirational programs and projects focusing supporting information. on transport, infrastructure, events, culture, health and knowledge, and business and investment to position the Gold An electronic version of this report is available on Coast with a competitive advantage – regionally, nationally the City website: cityofgoldcoast.com.au/annualreport and internationally. Language assistance About this report If you need an interpreter to help you contact the City of Gold The Annual Report provides an overview of City activities Coast, please call the Translating and Interpreting Service (TIS during the financial year, progress towards achieving the City National) on 13 1450 or visit the City website for further details. Vision ‘Inspired by Lifestyle. Driven by Opportunity’ and the City’s Corporate Plan Gold Coast 2022. It includes the City’s Chinese Simplified financial performance as at 30 June 2019, governance and 如果您需要口译员来帮助您联系黄金海岸市议会,请致电 statutory information. -

Combat Sport High Performance Approach Overview

Combat Sport High Performance Approach Overview From 1 January 2021, the national High Performance programs for Boxing, Judo and Taekwondo will be delivered by a newly established, sport owned, aggregated High Performance entity. This innovative and collaborative new approach will deliver enhanced High Performance outcomes for all three sports by ensuring a dedicated High Performance focus, significantly increased and more secure funding and access to a greater range of performance support services. This is a sport-led approach, delivering a sport-owned model. This new entity will be joint owned equally by the relevant National Sporting Organisations (NSOs), being Boxing Australia, Judo Australia and Australian Taekwondo. The NSOs will have strong links to the new entity through ongoing input into how the entity functions, its overall strategy and by continuing to lead the delivery of underpinning Performance Pathways programs. Each NSO will also have a representative on the new entity’s board. The Australian Institute of Sport’s (AIS) organisational strategy has shifted in recent years - no longer providing direct sport program delivery functions. As such the six-year AIS Combat Centre pilot project will cease operations at the end of 2020. This pilot project between the NSOs and the AIS, as well as two independent consultancy projects tasked with identifying the preferred delivery model for High Performance combat sport in Australia, have shown that there are enhanced performance benefits and opportunities that can be attained through an aggregated combat sport approach. The AIS is therefore very supportive of the establishment of this new High Performance combat-sport entity and is willing to strongly invest in it. -

The Depth and Breadth of Sponsorship by the Alcohol Industry in Australian Sport

The depth and breadth of sponsorship by the alcohol industry in Australian sport August 2018 Prepared by For Purpose for the Australian Department of Health Contents Executive Summary............................................................................................................................... 3 Background ....................................................................................................................................... 3 Analysis ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Findings ............................................................................................................................................. 3 NSO’s, competitions and events ................................................................................................... 3 Australian Rules and Rugby League SSOs and senior teams ......................................................... 4 Further observations ..................................................................................................................... 4 Background ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Analysis ................................................................................................................................................. 8 Generating a list of sports ................................................................................................................ -

Australian Olympians 2015

AUSTRALIAN OLYMPIANS 2015 - THIS ISSUE - REMEMBERING MOSCOw / ROAD TO RIO CHAMPIONS OF THE WORLD / ATHLETE TRANSITION / REUNIONS 2 4 Australian Olympians — 2015 5 6 Australian Olympians — 2015 10 CHAMPIONS OF THE WORLD Australian Olympians triumph taking on the world’s best. 18 INTERNATIONAL HONOURS Australian Olympians were celebrated JOHN COATES AC and recognised at the Annual Sport President, Australian Olympic Committee Australia Hall of Fame awards. Vice President, International Olympic Committee Congratulations to all our current athletes for a constitution represents over 100,000 Olympians 26 remarkable year of achievement. Our benchmark- worldwide, has now formed a genuine working ing results point to Australia’s constant standing in partnership with the IOC. Congratulations to Nat REMEMBERING the world’s top ten sporting nations. Cook who is now the IOC’s representative for Following on from the Sochi 2014 Olympic Oceania on the WOA Executive Board. We look for- MOScow Winter Games, 2015 saw some wonderful results ward to working closely with the new WOA and the The Australian Olympic spirit was from our winter athletes led by our two new World IOC on all matters relating to Olympians. put to the test as many athletes felt Champions Scotty James and Laura Peel. We now The foundations for our future Games are being the pressure to boycott the Games. 42 look forward to Australia’s representation at the laid with the next three editions of the Olympic Winter Youth Olympic Games, Lillehammer in Games being presented on our door step in Asia, February 2016. with the PyeongChang 2018 Olympic Winter 30 INSIDE The AOC was delighted to accept an invitation Games, Tokyo 2020 and then we return to Beijing in Contributing to to participate at the Pacific Games in Papua New 2022 for the Winter Games.