British Fvchives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PUBLIC RECORDS ACT 1958 (C

PUBLIC RECORDS ACT 1958 (c. 51)i, ii An Act to make new provision with respect to public records and the Public Record Office, and for connected purposes. [23rd July 1958] General responsibility of the Lord Chancellor for public records. 1. - (1) The direction of the Public Record Office shall be transferred from the Master of the Rolls to the Lord Chancellor, and the Lord Chancellor shall be generally responsible for the execution of this Act and shall supervise the care and preservation of public records. (2) There shall be an Advisory Council on Public Records to advise the Lord Chancellor on matters concerning public records in general and, in particular, on those aspects of the work of the Public Record Office which affect members of the public who make use of the facilities provided by the Public Record Office. The Master of the Rolls shall be chairman of the said Council and the remaining members of the Council shall be appointed by the Lord Chancellor on such terms as he may specify. [(2A) The matters on which the Advisory Council on Public Records may advise the Lord Chancellor include matters relating to the application of the Freedom of Information Act 2000 to information contained in public records which are historical records within the meaning of Part VI of that Act.iii] (3) The Lord Chancellor shall in every year lay before both Houses of Parliament a report on the work of the Public Record Office, which shall include any report made to him by the Advisory Council on Public Records. -

Angusalive What's On

What’s On October 2017 - March 2018 We’ve something for everyone! HEALTHY | ACTIVE | CREATIVE Libraries | Museums, Galleries & Archives | Sport & Leisure | Countryside Adventure | Theatre & Venues Dates for your diary National Coding Week Code Club Session 23 September Arbroath, Forfar and Free Carnoustie Libraries Bookbug All-In-One 4 October Monifieth Library Free 5 October Forfar Library Free 5 October Carnoustie Library Free 11 October Monifieth Library Free 12 October Forfar Library Free 12 October Carnoustie Library Free The Earl of Southesk in Saskatchewan - 1859 9 October Monifieth Library Free National Libraries Week 9 - 14 October All libraries Free ‘Discover something new in your Library’ Meet the Author 9 October Arbroath Library Free 10 October Forfar Library Free 11 October Carnoustie Library Free 12 October Kirriemuir Library Free Bookweek Scotland Extravaganza 29 November Reid Hall, Forfar Free December Capers Competition 1 - 24 December All libraries Free Bookbug’s Christmas Adventure 15 December Mobile Library at Crombie Park Free Meet local storyTELLEr - robbie Fotheringham 18 December Forfar Library Free Harry Potter Book Nights 1 February Kirriemuir Library Free 5 February Montrose Library Free 5 February Carnoustie Library Free 5 February Monifieth Library Free 5 February Arbroath Library Free 5 February Forfar Library Free 5 February Brechin Library Free World Book Day 2018 26 February - 3 March All libraries Free Children and Schooling in Olden Times 5 March Monifieth Library Free 6 March Kirriemuir Library Free -

A Field Awaits Its Next Audience

Victorian Paintings from London's Royal Academy: ” J* ml . ■ A Field Awaits Its Next Audience Peter Trippi Editor, Fine Art Connoisseur Figure l William Powell Frith (1819-1909), The Private View of the Royal Academy, 1881. 1883, oil on canvas, 40% x 77 inches (102.9 x 195.6 cm). Private collection -15- ALTHOUGH AMERICANS' REGARD FOR 19TH CENTURY European art has never been higher, we remain relatively unfamiliar with the artworks produced for the academies that once dominated the scene. This is due partly to the 20th century ascent of modernist artists, who naturally dis couraged study of the academic system they had rejected, and partly to American museums deciding to warehouse and sell off their academic holdings after 1930. In these more even-handed times, when seemingly everything is collectible, our understanding of the 19th century art world will never be complete if we do not look carefully at the academic works prized most highly by it. Our collective awareness is growing slowly, primarily through closer study of Paris, which, as capital of the late 19th century art world, was ruled not by Manet or Monet, but by J.-L. Gerome and A.-W. Bouguereau, among other Figure 2 Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) Study for And the Sea Gave Up the Dead Which Were in It: Male Figure. 1877-82, black and white chalk on brown paper, 12% x 8% inches (32.1 x 22 cm) Leighton House Museum, London Figure 3 Frederic Leighton (1830-1896) Elisha Raising the Son of the Shunamite Woman 1881, oil on canvas, 33 x 54 inches (83.8 x 137 cm) Leighton House Museum, London -16- J ! , /' i - / . -

THE PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE. Janet D. Hine

THE PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE. Janet D. Hine. (This paper was delivered by Miss Hine · at the last Association Conference.) I am very happy to talk to you tonight about the Publio Record Office in London. Introduction. There is no doubt that we are greatly indebted to this institution, for its example and for the way it has preserved quantities of the. source material of Australian histor,y. But in any case I feel a personal sense of gratitude to it because, I must guiltily admit, I. have spent some of the pleasantest and strangest hours of my life there. All this in spite of being quite literally allergic to it, or at least to its dust. Perhaps that added to the strangeness. The Joint Copying Project. From 1954 to 1957 I was in London, seconded to the office of the Agent General for New South Wales, to do work for the various departments of the Public Library of New South Wales. As I shall mention again later, I had several enquiries to make of the Public Record Office on behalf of the Archives Department, and I also used it to settle some comparatively small and self-contained queries sent from home and others rising out of the interests of the Agent General 1 s office. But by far the longest and most consistent · association I had with it was in connexion with the Joint Copying Project. This, as the present audience will doubtless know, is an · arrangement whereby the Commonwealth National Library and the Mitchell Library, in co-operation with the other State libraries of Australia, are having original overseas material of Australian and Pacific interest searched and copied for the use of students in this country. -

Croydon Borouigh of Culture 2023 Discussion Paper

CROYDON BOROUGH OF CULTURE 2023 Discussion paper following up Croydon Culture Network meeting 25 February 2020 Contents: Parts 1 Introduction 2 Croydon Council and Culture 3 The Importance of Croydon’s Cultural Activists 4 Culture and Class 5 Croydon’s Economic and Social Realities and Community 6 The Focus on Neighbourhoods 7 Audiences and Participants for 2023 8 The Relevance of Local History 9 Croydon’s Musical Heritage 10 Croydon Writers and Artists 11 Environment and Green History 12 The Use of Different Forms of Cultural Output 13 Engaging Schools 14 The Problem of Communication and the role of venues 15 System Change and Other Issues Appendices 1 An approach to activity about the environment and nature 2 Books relevant to Croydon 3 Footnotes Part 1. Introduction 1. The Culture Network meeting raised a number important issues and concerns that need to be addressed about the implementation of the award of Borough of Culture 2023 status. This is difficult as the two planning meetings that were announced would take place in March and April are not going ahead because of the coronavirus emergency. That does not mean that debate should stop. Many people involved in the Network will have more time to think about it as their events have been cancelled. Debate can take place by email, telephone, Skype, Zoom, etc. Several of the issues and concerns relate to overall aims of being Borough of Culture, as well as practical considerations. 2. There are several tensions and contradictions within the proposals that clearly could not be ironed out at the time the bid was submitted to the Mayor of London. -

Westminster City Archives

Westminster City Archives Information Sheet 10 Wills Wills After 1858 The records of the Probate Registry dating from 1858, can now only be found online, as the search room at High Holborn closed in December 2014, and the calendars were removed to storage. To search online, go to www.gov.uk/search-will-probate. You can see the Probate Calendar for free, but have to pay £10 per Will, which will be sent to you by e-mail. Not all entries actually have a will attached: Probate or Grant & Will: a will exists Administration (admon) & Will or Grant & Will: a will exists Letter of administration (admon): no will exists These pages have not been completely indexed, but you can use the England and Wales National Probate Calendar 1858-1966 on Ancestry.com. Invitation to the funeral of Mrs Mary Thomas, died 1768 Wills Before 1858 The jurisdiction for granting probate for a will was dictated either by where the deceased owned property or where they died. There are a large number of probate jurisdictions before 1858 (for details see the bibliography at the end of this leaflet). The records of the largest jurisdiction, the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, are held at:- The National Archives Ruskin Avenue Kew, Richmond London TW9 4DU Tel: 020-8392 5330 Now available online at: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/records/wills.htm City of Westminster Archives Centre 10 St Ann’s Street, London SW1P 2DE Tel: 020-7641 5180, fax: 020-7641 5179 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.westminster.gov.uk/archives July 2015 Westminster City Archives Wills -

Scotland's Epic Highland Games

Your guide to Scotland’s epic Highland games history & tradition :: power & passion :: colour & spectacle Introduction Scotland’s Highland games date back almost a thousand years. Held across the country from May to September, this national tradition is said to stem from the earliest days of the clan system. Chieftains would select their best fighters and nothing can compare to witnessing the spectacle of a household retainers after summoning their traditional Highland games set against the backdrop clansmen to a gathering to judge their athleticism, of the stunning Scottish scenery. strength and prowess in the martial arts, as well as their talent in music and dancing. From the playing fields of small towns and villages to the grounds of magnificent castles, Highland games Following the suppression of traditional Highland take place in a huge variety of settings. But whatever culture in the wake of the failed Jacobite rebellion their backdrop, you’ll discover time-honoured heavy under Bonnie Prince Charlie, the games went into events like the caber toss, hammer throw, shot put decline. It was Queen Victoria and her love for all and tug o’ war, track and field competitions and things Scottish which brought about their revival in tartan-clad Highland dancers, all wrapped up in the the 19th century. incredible sound of the marching pipes and drums. Today the influence of the Highland games reaches A spectacular celebration of community spirit and far beyond the country of its origin, with games held Scottish identity, Highland games are a chance to throughout the world including the USA, Canada, experience the very best in traditional Highland Australia, New Zealand and South Africa. -

Kensington and Chelsea

Kensington Open House London and Chelsea Self-Guided Itinerary Nearest station: Highstreet Kensington Leighton House Museum, 12 Holland Park Rd, Kensington, London W14 8LZ Originally the studio home of Lord Leighton, President of the Royal Academy, the house is one of the most remarkable buildings of 19C. The museum houses an outstanding collection of high Victorian art, including works by Leighton him- self. Directions: Walk south-west on Kensington High St/A315 towards Wrights Ln > Turn right onto Melbury Rd > Turn left onto Holland Park Rd 10 min (0.5 mi) 18 Stafford Terrace, Kensington, London W8 7BH From 1875, the home of the Punch cartoonist Edward Linley Sambourne, his wife Marion, their two children and their live-in servants. The house is recognised as the best surviving example of a late Victorian middle-class home in the UK. Directions: Walk north-east on Holland Park Rd towards St Mary Abbots Terrace > Turn right onto Melbury Rd > Turn left onto Kensington High St/A315 > Turn left onto Phillimore Gardens > Turn right onto Stafford Terrace 8 min (0.4 mi) Kensington Palace Gardens, London This wide open street runs alongside Kensington Gardens and features stereotypical architecture of the area. Large family homes line the street, most are now occupied by Embassies or other cultural companies. Page 1 Open House London Directions: Walk north-east on Stafford Terrace towards Argyll Rd > Turn right onto Argyll Rd > Turn left onto Kensington High St/A315 > Turn left onto Kensington Palace Gardens 14 min (0.7 mi) Embassy of Slovakia, Kensington, London W8 4QY Modern Brutalist-style building awarded by RIBA in 1971. -

British Design History Itinerary 2017

WINTERTHUR PROGRAM IN AMERICAN MATERIAL CULTURE EAMC 607, British Design History, 1530-1930 U.K. itinerary (short version) January 14-28, 2017 Saturday, January 14: Depart Philadelphia Sunday, January 15: Arrive London • Central London walking tour with Angus Lockyer, School for Oriental and African Studies, University of London: Southwark, City of London • Victoria & Albert Museum: Tour of Cast Room, self-guided tour of British Galleries Monday, January 16: London • East End walking tour with Angus Lockyer: Spitalsfields, Shoreditch, Hoxton • Geoffrye Museum: Tour of collections and Almshouse with Eleanor John, Director of Collections, Learning and Engagement, and Adam Bowett, Independent Furniture Historian; furniture study session with staff Tuesday, January 17: London • Hampton Court Palace: Tour of historic kitchens with Marc Meltonville, Historic Royal Palaces, Food Historian, Historic Kitchens Team; tour of King’s apartments with Sebastian Edwards, Deputy Chief Curator and Head of Collections, Historic Royal Palaces; self-guided tour of gardens Wednesday, January 18: London • St. Paul’s Cathedral: Self-guided tour • Goldsmiths’ Company: Tour of rooms Eleni Bide, Librarian; archives session; introduction to hallmarking with Eleni Bide • Museum of London: Self-guided tour of History of London galleries; exhibition “Fire! Fire!” • Wallace Collection. Collections tour with Dr. Helen Jacobsen, Senior Curator; furniture studio conservation tour with Jurgen Huber, Senior Furniture Conservator Thursday, January 19: Surrey and London • Polesden Lacey, Surrey: Garden tour with Jamie Harris, Head Gardner; “Unseen Spaces” tour with Caroline Williams, Senior Steward • Buckingham Palace: Guided tour with Desmond Shawe-Taylor, Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures, The Royal Collection • Dennis Severs’ House: ‘Silent Night’ tour and discussion with curator David Milne Friday, January 20: London • Westminster Abbey: Self-guided tour. -

Bulletin April 2009

SCOTTISH ASSOCIATION of FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETIES BULLETIN APRIL 2009 Executive Committee: Chairman: Bruce B Bishop; Deputy Chairman: Andrew Eadie; Secretary: Ken Nisbet; Treasurer: Vacant; Editor: Janet M Bishop; Publications Manager: Margaret Mackay ******************************************************************************************************************************************* *** A Note from Retiring Chairman The next meeting of SAFHS is on Saturday, 17 Neil W Murray October 2009 in the Boardroom, Central Youth Hostel, Haddington Place, Leith Walk, Edinburgh My involvement with SAFHS began in 1989, when I was asked by Highland Family History Society to be the SAFHS representative. I was appointed Deputy Chairman in March AGM & April Council Meeting 1996, and held that post until March 2006, when I was elected The Annual General Meeting and the April Council Meeting Chairman. So my service totals some 20 years! As I have were held on 4 April 2009, in the Boardroom, Central Youth previously indicated, I do feel it is time to move on, and give Hostel, Haddington Place, Leith Walk, Edinburgh. As usual, someone else the opportunity to come forward with fresh ideas. Minutes of the meeting have been sent to all member societies. Apart from SAFHS, I served as Chairman of Highland FHS from 1989-1997, and then from 1999-2002. I consider it an Contact Details: at the AGM, a form was handed out to all honour and pleasure to have served as an office-bearer of representatives present. Forms have also been sent to all SAFHS, and I deeply appreciate the fellowship I have member societies who did not have a representative at the experienced with so many people over the years. -

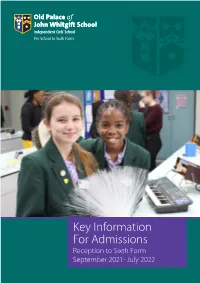

Key Information for Admissions Reception to Sixth Form September 2021 - July 2022 1 General Policy

Key Information For Admissions Reception to Sixth Form September 2021 - July 2022 1 General Policy Old Palace of John Whitgift School is an academically selective school which provides for students of above average academic ability. All entrants should be able to benefit from the academic education provided. General points of entry to Old Palace are Pre School, Reception, Year 7, and Year 12. The school does admit students into other year groups if residual places become available. Selection for admissions to fill any residual places is by assessment as and when vacancies become available. Selection for vacancies will be on merit with the highest ranked being admitted. All potential candidates and their families should take the opportunity to attend an Open Event to meet the students and staff and to look around the School. Copies of the Prospectus can be obtained at Open Events, from the Admissions Registrar or the School website: www.oldpalace.croydon.sch.uk A candidate who wishes to be considered for entry into the School is to complete and submit the online Application Form, via the school website, by the date specified in this booklet. To complete the online form, you will be asked to upload a copy of the photo page of your child’s passport and to make payment of the £100 registration fee. The Admissions team will require sight of your child’s original passport, full birth certificate, a proof of home address (for example, a utility or council tax bill), together with a copy of your daughter’s most recent school report (for entry to Year 1 and above). -

Spring/Summer 2021 News from Our Alumnae “I Went to School in a Tudor Palace”

Spring/Summer 2021 Old Palace Alumnae News Looking forward to a bright and sunny summer! Welcome from the Committee committee members, Hilary Gadd, the time this ‘News’ reaches you, the and one of our students, Sara A, have schools will have been able to return been trained as vaccinators, which is to a more normal routine at school. so worthwhile. And as the rapid roll- I would like to thank everyone who out continues we are looking forward has contributed to this edition, optimistically to a return to a more particularly those of you who normal existence by the summer. contacted me or Nicola Berry directly I have been following the news with your news and articles. Without Bulletins on the school website and items from our alumnae there am amazed at what the staff and wouldn’t be much of a newsletter to girls are managing to achieve with publish, so please keep sending in their online and virtual lessons. I your contributions; we really love to Dear All, have seen articles about PE activities, hear what you are all up to. Maths challenges and even Chemistry I hope this finds you managing to stay experiments all being undertaken at Please enjoy this edition, well and safe. As I prepare this edition home. Please do look up the Bulletins, of ‘News’, we are still unsure how long as they give you such an insight Katy Beck we will have to follow the advice of into what goes on at the school. I Newsletter Editor ‘Stay Local!’ but there is some good am sure that you would like to join news, that the vaccinations are me in sending Jane Burton, and all [email protected] being delivered very rapidly.