THE PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE. Janet D. Hine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PUBLIC RECORDS ACT 1958 (C

PUBLIC RECORDS ACT 1958 (c. 51)i, ii An Act to make new provision with respect to public records and the Public Record Office, and for connected purposes. [23rd July 1958] General responsibility of the Lord Chancellor for public records. 1. - (1) The direction of the Public Record Office shall be transferred from the Master of the Rolls to the Lord Chancellor, and the Lord Chancellor shall be generally responsible for the execution of this Act and shall supervise the care and preservation of public records. (2) There shall be an Advisory Council on Public Records to advise the Lord Chancellor on matters concerning public records in general and, in particular, on those aspects of the work of the Public Record Office which affect members of the public who make use of the facilities provided by the Public Record Office. The Master of the Rolls shall be chairman of the said Council and the remaining members of the Council shall be appointed by the Lord Chancellor on such terms as he may specify. [(2A) The matters on which the Advisory Council on Public Records may advise the Lord Chancellor include matters relating to the application of the Freedom of Information Act 2000 to information contained in public records which are historical records within the meaning of Part VI of that Act.iii] (3) The Lord Chancellor shall in every year lay before both Houses of Parliament a report on the work of the Public Record Office, which shall include any report made to him by the Advisory Council on Public Records. -

Westminster City Archives

Westminster City Archives Information Sheet 10 Wills Wills After 1858 The records of the Probate Registry dating from 1858, can now only be found online, as the search room at High Holborn closed in December 2014, and the calendars were removed to storage. To search online, go to www.gov.uk/search-will-probate. You can see the Probate Calendar for free, but have to pay £10 per Will, which will be sent to you by e-mail. Not all entries actually have a will attached: Probate or Grant & Will: a will exists Administration (admon) & Will or Grant & Will: a will exists Letter of administration (admon): no will exists These pages have not been completely indexed, but you can use the England and Wales National Probate Calendar 1858-1966 on Ancestry.com. Invitation to the funeral of Mrs Mary Thomas, died 1768 Wills Before 1858 The jurisdiction for granting probate for a will was dictated either by where the deceased owned property or where they died. There are a large number of probate jurisdictions before 1858 (for details see the bibliography at the end of this leaflet). The records of the largest jurisdiction, the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, are held at:- The National Archives Ruskin Avenue Kew, Richmond London TW9 4DU Tel: 020-8392 5330 Now available online at: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/records/wills.htm City of Westminster Archives Centre 10 St Ann’s Street, London SW1P 2DE Tel: 020-7641 5180, fax: 020-7641 5179 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.westminster.gov.uk/archives July 2015 Westminster City Archives Wills -

The Colonial Office Group of the Public Record Office, London with Particular Reference to Atlantic Canada

THE COLONIAL OFFICE GROUP OF THE PUBLIC RECORD OFFICE, LONDON WITH PARTICULAR REFERENCE TO ATLANTIC CANADA PETER JOHN BOWER PUBLIC ARCHIVES OF CANADA rn~ILL= - importance of the Coioniai office1 records housed in the Public Record Office, London, to an under- standing of the Canadian experience has long been recog- nized by our archivists and scholars. In the past one hundred years, the Public Archives of Canada has acquired contemporary manuscript duplicates of documents no longer wanted or needed at Chancery Lane, but more importantly has utilized probably every copying technique known to improve its collection. Painfully slow and tedious hand- transcription was the dominant technique until roughly the time of the Second World War, supplemented periodi- cally by typescript and various photoduplication methods. The introduction of microfilming, which Dominion Archivist W. Kaye Lamb viewed as ushering in a new era of service to Canadian scholars2, and the installation of a P.A.C. directed camera crew in the P.R.O. initiated a duplica- tion programme which in the next decade and a half dwarfed the entire production of copies prepared in the preceding seventy years. It is probably true that no other former British possession or colony has undertaken so concerted an effort to collect copies of these records which touch upon almost every aspect of colonial history. While the significance of the British records for . 1 For the sake of convenience, the term "Colonial Office'' will be used rather loosely from time to time to include which might more properly be described as precur- sors of the department. -

Never‐Never Land and Wonderland? British and American Policy on Intelligence Archives Richard J

This article was downloaded by: [University of Warwick] On: 13 November 2012, At: 17:12 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Contemporary Record Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fcbh19 Never‐never land and wonderland? British and American policy on intelligence archives Richard J. Aldrich a a Lecturer in Politics, University of Nottingham Version of record first published: 25 Jun 2008. To cite this article: Richard J. Aldrich (1994): Never‐never land and wonderland? British and American policy on intelligence archives, Contemporary Record, 8:1, 133-152 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13619469408581285 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/ terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Downloaded by [University of Warwick] at 17:12 13 November 2012 ARCHIVE REPORT Never-Never Land and Wonderland? British and American Policy on Intelligence Archives RICHARD J. -

A Brief History of the Public Record Office

General Information Series The Public Record Office: A Brief History A public record is a document created or stored by a government in the course of its business. In the middle ages, the public records were the king's personal records, created in the course of his business of governing the kingdom. The king moved around his estates from day to day, carrying all his documents around with him, along with his gold, jewels, and other personal belongings. From the early twelfth century, royal administration became more complex: Two great departments of state gradually evolved: the Exchequer, which dealt with the financial aspects of medieval government, and the Chancery, the administrative side. They generated their own records and, in addition, documents sent to them also had to be properly organised and recorded. Instructions issued to individuals and institutions (known as Writs), records relating to the courts of law, plus detailed accounts of royal income and expenditure, came to be copied 'for the record'. Copies were made on cleaned, dried and smoothed sheep-skin (parchment). For convenience, these copies were 'enrolled' - that is, sheets of parchment were sewn together to create rolls for easy carriage and storage. The person whose responsibility it was to care for these became known as 'Master of the Rolls'. Eventually, there were far too many records for the king to carry around with him, even if, by this stage, the entire royal court was becoming less mobile, staying in only a few major palaces each year. The problem then was where to store the records. From the sixteenth to eighteenth centuries, there were over two hundred sites in London and elsewhere in use. -

The British Historical Manuscripts Commission

THE BRITISH HISTORICAL MANUSCRIPTS COMMISSION V ' I HE establishment of the Royal Commission for Historical Downloaded from http://meridian.allenpress.com/american-archivist/article-pdf/7/1/41/2741992/aarc_7_1_m625418843u57265.pdf by guest on 28 September 2021 Manuscripts in 1869 was an outgrowth of the concern for public records which had reached a climax only a few years earlier. As far back as 1661, William Prynne was appointed by Charles II to care for the public records in the Tower of London. Prynne described them as a "confused chaos, under corroding, putrifying cobwebs, dust and filth. ." In attempting to rescue them he employed suc- cessively "old clerks, soldiers and women," but all abandoned the job as too dirty and unwholesome. Prynne and his clerk cleaned and sorted them. He found, as he had expected, "many rare ancient precious pearls and golden records."1 Nevertheless, by 1800 the condition of the records was deplorable again, and a Record Commission was appointed for their custody and management. It was composed of men of distinction, was liberally supported, and it published various important documents. In spite of its work, the commission could not cope with the scattered records and unsuitable depositories. Of the latter, one was a room in the Tower of London over a gunpowder vault and next to a steam pipe passage; others were cellars and stables. The agitation aroused by the commission led to passage of the Public Records Act in 1838. The care and administration of the records was restored to the Mas- ter or Keeper of the Rolls, in conjunction with the Treasury depart- ment, with enlarged powers. -

Committee Report Template

Committee: Dated: Culture, Heritage and Libraries Committee 25 January 2021 Subject: London Metropolitan Archives: accreditation Public Which outcomes in the City Corporation’s Corporate Plan 3, 7, 9, 10 and 12 does this proposal aim to impact directly? Does this proposal require extra revenue and/or capital N spending? If so, how much? N/A What is the source of Funding? N/A Has this Funding Source been agreed with the N/A Chamberlain’s Department? Report of: Peter Lisley, Assistant Town Clerk and For Information Director of Major Projects Report author: Geoff Pick, Director, London Metropolitan Archives Summary This report provides details of the award of Archive Service Accreditation to London Metropolitan Archives (LMA) which was reported verbally to Members at the meeting of this Committee in November 2020. Accreditation is the national quality standard in the archive sector and LMA was one of the first archive services in the UK to achieve this status in 2014. It has to be re-applied for in full every six years. The overall view of the assessors was that they: welcomed this impressive application from a major archive service which delivers across its extensive remit. They noted particularly the service’s success as a core element of the Corporation of London’s work; its proactive and successful engagement across diverse communities; a very strong management approach; and the range of improvement activity seen since its original successful application for the award. Recommendation(s) Members are asked to note the report. Main Report -

10617 DPC Annual Report 2008 Insides.Indd

ce Park, Heslington, Yo York Scien rk YO10 entre, 5DG ion C ovat Telephone 019 Inn 04 435 The 362 Website www.dpco nline.org Email info @dp conl ine .org accessible tomorrow Our digital memory O u r D 9 0 0 i 2 - g 8 0 0 2 A t n r n o u p a e l R i t a l M e m o r w y o r a r c o c e m s o s t i b l e Contents Chairman’s Introduction 01 DPC Activities 05 Papers, Presentations and Reports 08 Leadership Programme 15 Technology Watch Report 16 What’s New In Digital Preservation 17 The Digital Preservation and DPC-Discussion email lists 17 Members’ Activities – Full Members 19 Members’ Activities – Associate Members 29 Allied Organisations 38 DPC Board of Directors 38 2008-2009 Financial Statement 40 [Cover Image] View of the Robert Adam dome ceiling in HM General Register House, The National Archives of Scotland, Edinburgh. Image on [Contents], [Page 39] and [Page 40] courtesy of Mike Braham Photography, York. All other images courtesy of DPC and its members. Designed and produced by [Rubber Band] www.rubberbandisthe.biz Chairman’s Introduction [1] THE CORE TASK OF ENSURING THAT OUR DIGITAL MEMORY IS ACCESSIBLE TOMORROW REMAINS The aim of the Digital Preservation Coalition the core task of ensuring that our digital is to secure the preservation of digital memory is accessible tomorrow remains. resources in the UK and to work with While developing the plan was the work of others internationally to secure our global Executive Director, Frances Boyle, delivery digital memory and knowledge base. -

Westminster City Archives

Westminster City Archives Information Sheet 4 Westminster Registers not held at Westminster City Archives This list includes the records of Anglican churches, chapels, chapels royal and workhouses within the current City of Westminster which, for various reasons, are not held at City of Westminster Archives Centre. Microfilm copies of the parish registers for St Marylebone and Paddington are kept here. There is a brief section on Orthodox Christian and Jewish records. For Roman Catholic records, see Information Sheet 2, and for Non-Conformist records, see Information Sheet 3. Chapels Royal For further information, contact Royal Household Enquiries on 020-7930 4832 or the National Archives at Kew (formerly the Public Record Office). The Chapel Royal, St James’s Palace by Thomas H Shepherd Chapels Royal Registers held at St James’s Palace St James's Palace 1675-1709 and 1647 Now at TNA, copy only at St James's Baptisms 1709-1755 1789-1897 1897-1905 1906-the present Churchings 1869-1873 Confirmations 1885 1959-the present Marriages 1709-1754 1905-the present 1933-the present City of Westminster Archives Centre 10 St Ann’s Street, London SW1P 2DE Tel: 020-7641 5180, fax: 020-7641 5179 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.westminster.gov.uk/archives January 2010 Westminster City Archives Westminster Registers not held Information Sheet 4 at Westminster City Archives Chapels Royal Registers held at St James’s Palace (continued) Buckingham Palace Baptisms 1843-1864 Marriages 1843, 1849 & 1857 Churchings 1843-1857 Kensington Palace Baptisms 1721-1764 & 1789 1840-1900 Marriages 1721-1751,1872 & 1889 Whitehall Palace Baptisms 1753-1796 1817-1825, 1853-1890 Marriages 1704-1754 & 1807 1824 & 1829 1839-1889 NB Marriage licences are at TNA. -

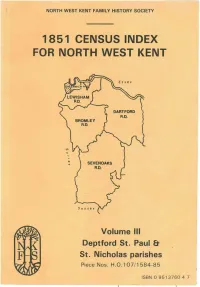

1851 Census Index for North West Kent

NORTH WEST KENT FAMILY HISTORY SOCIETY 1851 CENSUS INDEX FOR NORTH WEST KENT . LEWISHAM ’ 9.0. DARTFORD [in BROMLEY RD. SEVENOAKS RII Volume III Deptford St. Paul & St. Nicholas parishes Piece Nos. H.O.107/1584—85 ISBN()9513760447 North West Kent Family History Society 1851 CENSUS INDEX FOR NORTH WEST KENT Volume III Deptford St. Paul and St. Nicholas parishes Piece Numbers H0 107/ 1584, H0 107/ 1585 1990 Contents Introduction ii. Location of Census Microfilms and Transcripts iii. Historical Background _ iv. Arrangement of the Deptford 1851 Census Returns xi. Guide to Enumeration Districts and Folio Numbers xiv. Index of Streets 1—2. INDEX OF NAMES 3—166. Society Publications 167. (c) North West Kent Family History Society, 1990 ISBN 0 9513760 4 7 INTRODUCTION This volume is the third in the Society's series of indexes to the 1851 census of _ north west Kent, and is the result of some five years work. Its production would not have been possible without the help of a number of volunteers, and I would like to record my thanks and those of the Society to: — The transcribers and checkers who have helped with Deptford St. Paul and St. Nicholas — i. e. Bob Crouch, Rose Medley, Mary Mullett, Edna Reynolds, Helen Norris, Norman Sears, Len Waghorn and Malcolm Youngs. Of these, I would particularly like to single out Len Waghorn, who alone transcribed 20 of the 35 enumeration districts. -— Members of the Society with BBC or MS—DOS microcomputers, for their work on entering the data into computer files — i. -

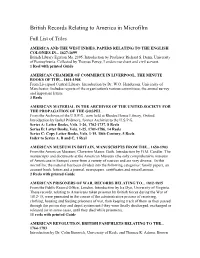

British Records Relating to America in Microfilm

British Records Relating to America in Microfilm Full List of Titles AMERICA AND THE WEST INDIES, PAPERS RELATING TO THE ENGLISH COLONIES IN... 1627-1699 British Library Egerton Ms. 2395. Introduction by Professor Richard S. Dunn, University of Pennsylvania. Collected by Thomas Povey, London merchant and civil servant. 1 Reel with printed Guide AMERICAN CHAMBER OF COMMERCE IN LIVERPOOL, THE MINUTE BOOKS OF THE... 1801-1908 From Liverpool Central Library. Introduction by Dr. W.O. Henderson, University of Manchester. Includes reports of the organisation's various committees, the annual survey and important letters. 3 Reels AMERICAN MATERIAL IN THE ARCHIVES OF THE UNITED SOCIETY FOR THE PROPAGATION OF THE GOSPEL From the Archives of the U.S.P.G., now held at Rhodes House Library, Oxford. Introduction by Isobel Pridmore, former Archivist to the U.S.P.G. Series A: Letter Books, Vols. 1-26, 1702-1737, 8 Reels Series B: Letter Books, Vols. 1-25, 1701-1786, 14 Reels Series C: Copy Letter Books, Vols. 1-15, 18th Century, 5 Reels Index to Series A, B and C, 1 Reel AMERICAN MUSEUM IN BRITAIN, MANUSCRIPTS FROM THE... 1650-1903 From the American Museum, Claverton Manor, Bath. Introduction by G.M. Candler. The manuscripts and documents at the American Museum (the only comprehensive museum of Americana in Europe) come from a variety of sources and are very diverse. In this microfilm, the material has been divided into the following categories: family papers, an account book, letters and a journal, newspapers, certificates and miscellaneous. 2 Reels with printed Guide AMERICAN PRISONERS OF WAR, RECORDS RELATING TO.. -

ARCHIVES SECOND EDITION SECOND Edmon Aguide to Archive Resources in the United Kingdom

BRITISH ARCHIVES SECOND EDITION SECOND EDmON AGuide to Archive Resources in the United Kingdom JANET FOSTER &JUIlA SHEPPARD M stockton press © Macmillan Publishers Ltd, 1982, 1989 Softcover reprint ofthe hardcover 2nd edition 1989 978-0-333-44347-7 All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without permission. Published in the United States and Canada by STOCKTON PRESS 1989 15 East 26th Street, New York, N.Y. 10010. Library of Congress Cataloging-In-Publication Data Foster, Janet. British archives/by Janet Foster and Julia Sheppard. - 2nd ed. p. cm. Bibliography: p. Includes indexes. ISBN 978-0-935859-74-4 1. Archives - Great Britain - Directories. I. Sheppard, Julia. II. Title. CD1040.F67 1989 027.541- dc20 89-4603 CIP Published in the United Kingdom by MACMILLAN PUBLISHERS LTD aournals Division), 1989 Distributed by Globe Book Services Ltd BruneI Road, Houndmills Basingstoke, Hants RG21 2XS British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Foster, Janet, 1948- British archives. - 2nd ed. 1. Great Britain. Record repositories - Directories I. Title II. Sheppard, Julia 027.041 ISBN 978-1-349-09567-4 ISBN 978-1-349-09565-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-09565-0 Contents Acknowledgements VI Introduction Vll How to Use this Book XIV Alphabetical Listing xv List of Entries by County XXXI Useful Addresses xlvi Useful Publications Iii Entries 1 Appendix I: Institutions which have placed their archives elsewhere 791 Appendix II: Institutions which reported having no archives 793 Appendix III: Institutions which did not respond to questionnaire 796 Index to Collections 797 Guide to Key Subjects 829 Acknowledgements We acknowledge and thank the contributors to British Archives, without whom the book would not exist.