Linköping University Postprint Music Under Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nepal, November 2005

Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Country Profile: Nepal, November 2005 COUNTRY PROFILE: NEPAL November 2005 COUNTRY Formal Name: Kingdom of Nepal (“Nepal Adhirajya” in Nepali). Short Form: Nepal. Term for Citizen(s): Nepalese. Click to Enlarge Image Capital: Kathmandu. Major Cities: According to the 2001 census, only Kathmandu had a population of more than 500,000. The only other cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants were Biratnagar, Birgunj, Lalitpur, and Pokhara. Independence: In 1768 Prithvi Narayan Shah unified a number of states in the Kathmandu Valley under the Kingdom of Gorkha. Nepal recognizes National Unity Day (January 11) to commemorate this achievement. Public Holidays: Numerous holidays and religious festivals are observed in particular regions and by particular religions. Holiday dates also may vary by year and locality as a result of the multiple calendars in use—including two solar and three lunar calendars—and different astrological calculations by religious authorities. In fact, holidays may not be observed if religious authorities deem the date to be inauspicious for a specific year. The following holidays are observed nationwide: Sahid Diwash (Martyrs’ Day; movable date in January); National Unity Day and birthday of Prithvi Narayan Shah (January 11); Maha Shiva Ratri (Great Shiva’s Night, movable date in February or March); Rashtriya Prajatantra Diwash (National Democracy Day, movable date in February); Falgu Purnima, or Holi (movable date in February or March); Ram Nawami (Rama’s Birthday, movable date in March or April); Nepali New Year (movable date in April); Buddha’s Birthday (movable date in April or May); King Gyanendra’s Birthday (July 7); Janai Purnima (Sacred Thread Ceremony, movable date in August); Children’s Day (movable date in August); Dashain (Durga Puja Festival, movable set of five days over a 15-day period in September or October); Diwali/Tihar (Festival of Lights and Laxmi Puja, movable set of five days in October); and Sambhidhan Diwash (Constitution Day, movable date in November). -

Nepal Side, We Must Mention Prof

The Journal of Newar Studies Swayambhv, Ifliihichaitya Number - 2 NS 1119 (TheJournal Of Newar Studies) NUmkL2 U19fi99&99 It has ken a great pleasure bringing out the second issue of EdltLlo the journal d Newar Studies lijiiiina'. We would like to thank Daya R Sha a Gauriehankar Marw&~r Ph.D all the members an bers for their encouraging comments and financial support. ivc csp~iilly:-l*-. urank Prof. Uma Shrestha, Western Prof.- Todd ttwria Oregon Univers~ty,who gave life to this journd while it was still in its embryonic stage. From the Nepal side, we must mention Prof. Tej Shta Sudip Sbakya Ratna Kanskar, Mr. Ram Shakya and Mr. Labha Ram Tuladhar who helped us in so many ways. Due to our wish to publish the first issue of the journal on the Sd Fl~ternatioaalNepal Rh&a levi occasion of New Nepal Samht Year day {Mhapujii), we mhed at the (INBSS) Pdand. Orcgon USA last minute and spent less time in careful editing. Our computer Nepfh %P Puch3h Amaica Orcgon Branch software caused us muble in converting the files fm various subrmttd formats into a unified format. We learn while we work. Constructive are welcome we try Daya R Shakya comments and will to incorporate - suggestions as much as we can. Atedew We have received an enormous st mount of comments, Uma Shrcdha P$.D.Gaurisbankar Manandhar PIID .-m -C-.. Lhwakar Mabajan, Jagadish B Mathema suggestions, appreciations and so forth, (pia IcleI to page 94) Puma Babndur Ranjht including some ~riousconcern abut whether or not this journal Rt&ld Rqmmtatieca should include languages other than English. -

Participant I Directory

PARTICIPANT I DIRECTORY FY 1974-1978 SUPPLEMENT, JANUARY 1979 UPDATED, SEPTEMBER 1985 PARTICIPANT DIRECTORY 1974 - 1978 UPDATED 1985 Table of Contents Page Number Section ... ... ... ... ... ... ... i Preface ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ii List of Acronyms ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... A-i Alphabetical Index of Participants ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... G-I Geographical Location of Participants by Area of Training ... ... ... ... U-i ... ...*... ... ... ... Brief Description of the Survey and Utilization Tally Summary ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 1-1 Principal Listing of Participants : Code 100, Agriculture and Natural Resources ... ... ... 2-1 Code 200, Industry and Mining* ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 3-1 Code 300, Transportation ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 5-1 Code 500, Health aud Sanitation ... ... ... ...... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 6-1 Code 600, Education ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 7-1 Code 700, Public Administration ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 8-1 Code 800, Community Development ... ... ... .... ... ... ... ... ... 9-i Code 900, Miscellaneous* ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... ... * No participants are listed under these two codes. Pre face This volume updates the USAID/Nepal Participant Directory covering the period FY 1974- FY 1978. In this edition, the "Home Address", "Training Period" where necessary, "Present -

Chittadhar Hridaya's Sugata Saurabha: the Known and Unknown in the Composition of the Epic Todd Lewis and Subarna Man Tuladhar

Chittadhar Hridaya's Sugata Saurabha: The Known and Unknown in the Composition of the Epic Todd Lewis and Subarna Man Tuladhar 1. The poet's experience: "I am a Buddhist by birth. So I need not explain why I revere the Lord Buddha. I was quite a young boy when I began to learn the devanagari alphabet and it so happened this was about the time when the Reverend Nisthananda published his N ewari translation of the Lalitavistara that recounts the life of the Buddha. Our Buddhist priests used to come to our house and recite a few pages of it and they left each installment with us so I could read it. As it was in devanagari and printed, I had no trouble reading it smoothly. Indeed, as I had just learned the characters, I loved reading it. Children derive a lot of satisfaction from reading books in their own native language. Each time I would quickly work through what the priest had brought and I waited eagerly for the next visit and the next installment. By the end of the year I had made it through the whole book. When I grew older I also learned to read Hindi and started to read books such as the Dhammapada, the life story of the Buddha, and others which had been translated into that language." 2. Chapters in Sugata Saurabha 1 Lumbini 8 The Great Renullciation 15 Twelve Years of Itinerant Preaching 2. Family Tree 9 Yashodhara 16 A Dispute over Water 3 Nativity 10 Attaining Enlightenment 17 The Monastery Built by Visakha 4 Mother I I Basic Teachings 18 Devadatta's Sacrilege 5 A Pleasant Childhood 12 The Blessed One in Kapilavastu 19 Entry into Nirvana 6 Education 13 Handsome Nanda 7 Marriage 14 The Great Lay Disciple 3. -

Final Senior Fellowship Report

FINAL SENIOR FELLOWSHIP REPORT NAME OF THE FIELD: DANCE AND DANCE MUSIC SUB FIELD: MANIPURI FILE NO : CCRT/SF – 3/106/2015 A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF TWO VAISHNAVISM INFLUENCED CLASSICAL DANCE FORM, SATRIYA AND MANIPURI, FROM THE NORTH EAST INDIA NAME : REKHA TALUKDAR KALITA VILL – SARPARA. PO – SARPARA. PS- PALASBARI (MIRZA) DIST – KAMRUP (ASSAM) PIN NO _ 781122 MOBILE NO – 9854491051 0 HISTORY OF SATRIYA AND MANIPURI DANCE Satrya Dance: To know the history of Satriya dance firstly we have to mention that it is a unique and completely self creation of the great Guru Mahapurusha Shri Shankardeva. Shri Shankardeva was a polymath, a saint, scholar, great poet, play Wright, social-religious reformer and a figure of importance in cultural and religious history of Assam and India. In the 15th and 16th century, the founder of Nava Vaishnavism Mahapurusha Shri Shankardeva created the beautiful dance form which is used in the act called the Ankiya Bhaona. 1 Today it is recognised as a prime Indian classical dance like the Bharatnatyam, Odishi, and Kathak etc. According to the Natya Shastra, and Abhinaya Darpan it is found that before Shankardeva's time i.e. in the 2nd century BC. Some traditional dances were performed in ancient Assam. Again in the Kalika Purana, which was written in the 11th century, we found that in that time also there were uses of songs, musical instruments and dance along with Mudras of 108 types. Those Mudras are used in the Ojha Pali dance and Satriya dance later as the “Nritya“ and “Nritya hasta”. Besides, we found proof that in the temples of ancient Assam, there were use of “Nati” and “Devadashi Nritya” to please God. -

2Nd International Folk Music Film Festival Catalogue 2012

Dedications The 3 days of International Folk Music Film Festival –Nepal 2012 will each be dedicated to different people who have devoted a considerable portion of their life’s work to the promotion, documentation and preservation of traditional musicians and associated artists, their music and music culture. They are John Baily and Veronica Doubleday, UK, Les Blank, USA and Ramsaran Darnal (1937–2011) from Nepal. John Baily & Veronica Doubleday, Ethnomusicologists, Musicians and Writers, husband and wife John and Veronica frequently perform together in concert and often with noted Afghan musicians. They have dedicated their life’s work to the people and music of Afghanistan and have supported Afghan musicians and their families throughout the prolonged conflicts. John Baily, Emeritus Professor, Goldsmiths, London University, began his ethnomusicological work in Afghanistan in 1973 also becoming a skilled musician particularly on the Afghan rubab and dutar. Prior to this he had learnt tabla with Krishna Govinda on an extended visit to Kathmandu in 1971. From 1984-5 John trained in anthropological filmmaking and directed the award-winning film Amir: An Afghan Refugee Musician’s life in Peshawar, Pakistan. He is the author of many articles and book chapters and has recently published Songs from Kabul: The Spiritual Music of Ustad Amir Mohammed. John is presently helping to develop The Afghanistan National Institute of Music. Veronica Doubleday, visiting lecturer, the University of alone from Folk Alliance International and from the International Brighton. Veronica’s ethnomusicological work focuses on Afghan Documentary Association. music, women’s music and gender issues and she has published Native filmmaker, Samrat Kharel, has written, “Les Blank’s films many articles on these subjects. -

A Young Person's Guide to the Cultural Heritage of the Kathmandu

A Young Person’s Guide to the Cultural Herita ge of the Kathmandu Valley: The Song Kaulā Kachalā and Its Video Ingemar Grandin Linköping University Post Print N.B.: When citing this work, cite the original article. Original Publication: Ingemar Grandin, AYoung Person’s Guide to the Cultural Heritage of the Kathmandu Valley: The Song Kaulā Kachalā and Its Video, 2015, Studies in Nepali History and Society, (19 (2014)), 2, 231-267. Copyright: The Authors. http://www.martinchautari.org.np/ Postprint available at: Linköping University Electronic Press http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:liu:diva-123364 THE SONG KAULA¯ KACHALA¯ AND ITS VIDEO | 231 A YOUNG PERSON’S GUIDE TO THE CULTURAL HERITAGE OF THE KATHMANDU VALLEY: THE SONG KAULA- KACHALA- AND ITS VIDEO Ingemar Grandin There is no doubt that the Newar culture of the Kathmandu Valley has attracted a lot of scholarly attention. Scholars who themselves belong to the Newar community have contributed prominently to the literature (for instance, Malla 1982; Shrestha 2012), yet it is the involvement of scholars from almost all over the world (from Japan in Asia over Australia and Europe to North America) that is particularly striking. It seems that whatever aspect of the Newar civilization you think of – say, its arts (Slusser 1982), use of space (Herdick 1988), its performances of dance, music and drama (van den Hoek 2004; Wegner 1986; Toffin 2010), its specific Hinduism (Levy 1990), or its equally specific Buddhism (Gellner 1992) – you will find it covered at length by foreign scholars in many articles and in at least one book-length study. -

Devkota's Voice of Rebellion and Social Critique in the Lunatic

© IJARW | ISSN (O) - 2582-1008 April 2020 | Vol. 1 Issue. 10 www.ijarw.com DEVKOTA’S VOICE OF REBELLION AND SOCIAL CRITIQUE IN THE LUNATIC Dr. Ramesh Prasad Adhikary Assistant Professor, Tribhuwan University, Kathmandu, M.M. Campus, Nepalgunj, Nepal ABSTRACT The present research paper explores Laxmi Prasad Devkota’s use of nonconformist theme and style in his seminal poem The Lunatic. His nonconformist theme and his style challenge the traditional values and norms prevailing in the contemporary society. The poet develops his consciousness of change and antitraditional view against the contemporary society in his poem The Lunatic. He challenges the contemporary traditional social norms, systems and values in order to flow his consciousness of change and progress. Devkota is against the traditional Rana regime and advocated for consciousness of change, progress and democracy in his literary work. Keyword: Descent voice, nonconformist theme, social rebellion, modernity, voice for freedom 1. INTRODUCTION DEVKOTA AS A DISSENT consciousness of his age that’s why to change the AND REBELLIOUS POET age from the poverty, injustice, emptiness and domination; he sees the bullets power rather than The Lunatic presents Devkota’s anger and satire other. Only revolution and bullets can be the over the-then society. In his poems, he protests all suitable solutions to these problems. In his poems, contemporary traditional and religion oriented Devkota tries to inspire all the Nepalese people to rules, values and system. Devkota introduces change the thinking, morality and behavior many anti-traditional themes from the according to the age. contemporary society in his poem. He deals with the themes like domination, poverty, employment, Moreover, Devkota passed his life under the rules and hunger and education system of Nepal. -

POST-MORTEM Round, and the Outcome Will Be Decided at the Party’S Upcoming Convention in Pokhara

#24 5 - 11 January 2001 20 pages Rs 20 EXCLUSIVE 69-41 The ruling party’s vicious internal power struggle is now in its final POST-MORTEM round, and the outcome will be decided at the party’s upcoming convention in Pokhara. But before In the 36 hours of mobocracy that ruled that, there was the small matter of Kathmandus streets last week, we caught the no-trust vote against Prime Minister Girija Prasad Koirala that a glimpse of an area of darkness in our wannabe Sher Bahadur Deuba countrys soul. wanted to settle first. The vote was set for 28 December, and both BINOD BHATTARAI factions did some grandstanding ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ University. The government was not there at about secret or open ballot to hide n 26-27 December, Nepal had no a critical moment. It was only on Wednesday the fact that they were both terrified government. Legitimate political parties afternoon, after things began to get really out o of control that the Prime Ministers office of losing. cowered, citizens were afraid to speak Both sides met for the duel in out, the capital sank into an anarchic limbo. It began taking stock. The only party that the murky fog-shrouded Singha was all the more shocking because we had showed some sanity was the main opposition Durbar on Thursday morning. The been brought up to believe that things like this UML, which began drafting its now-famous rebels led by Deuba boycotted the werent supposed to happen in peaceful Nepal. statement warning people not to fish in vote when the Koirala camp It wont be the same again: Nepalis of all muddy waters. -

Nepali Times Welcomes Feedback

#327 15 - 21 December 2006 16 pages Rs 30 Weekly Internet Poll # 327 Q. How is the country doing today compared with before 24 April 2006? Total votes: 4,605 Makeshift peace Weekly Internet Poll # 328. To vote go to: www.nepalitimes.com Q. Do you think the interim constitution will be finalised before year-end? EMPTY HUTS: Everyday a new camp to house 10 fighters is built at the Dasratpur cantonment site. The camps, which number nearly 100, are empty. NARESH NEWAR NARESH NEWAR in SURKHET Maoists themselves are getting even battle-hardened guerrillas together it will be villagers living impatient with the lack of found conditions too rough in outside camps who will have to t is the price the Nepali facilities. the camp and moved to farmers’ bear the burden of taking care of people have come to pay for When Pushpa Kamal Dahal homes in Dasratpur. the Maoists. But most are I peace: a messy, undefined, tells the prime minister and the This is creating problems for philosophical about it. “We have under-funded, and half-hearted UN in Kathmandu to speed up villagers who have to house up to fed them all these years, it is effort to confine the Maoists and arms management, he is eight Maoists each. We asked Bir nothing new,” rues Dasratpur their arms. responding to increasing pressure Bhusal, a local shopkeeper, how farmer Bishnu Barlami Magar, A visit to a Maoist cantonment from cadre like those here in long he could go on like this. even though there at Dasratpur, north of Surkhet, western Nepal who are getting “What do you want us to say,” he are armed Maoists Editorial p2 showed how everyone is just frustrated with roughing it in the retorted sarcastically, “what can within earshot. -

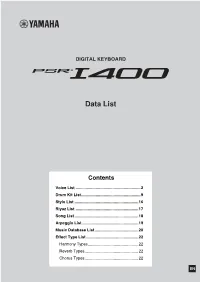

PSR-I400 Data List Voice List

DIGITAL KEYBOARD Data List Contents Voice List ..........................................................2 Drum Kit List.....................................................9 Style List .........................................................16 Riyaz List ........................................................17 Song List .........................................................18 Arpeggio List ..................................................19 Music Database List.......................................20 Effect Type List...............................................22 Harmony Types.............................................22 Reverb Types................................................22 Chorus Types................................................22 EN Voice List Maximum Polyphony The instrument has 48-note maximum polyphony. This means that it NOTE can play a maximum of up to 48 notes at once, regardless of what • The Voice List includes MIDI program change numbers functions are used. Auto accompaniment uses a number of the for each voice. Use these program change numbers available notes, so when auto accompaniment is used the total number when playing the instrument via MIDI from an external of available notes for playing on the keyboard is correspondingly device. reduced. The same applies to the Split Voice and Song functions. If the • Program change numbers are often specified as maximum polyphony is exceeded, earlier played notes will be cut off and numbers “0–127.” Since this list uses a “1–128” the most recent notes have -

Documenting Nepalese Musical Traditions

DOCUMENTING NEPALESE MUSICAL TRADITIONS Gert-Matthias We g n e r This paper gives a brief but updated account of the fieldwork car- ried out by ethnomusicologists in Nepal with some information on the re c o rded and published material. The re c e n t l y-founded (1996) Kathmandu University Department of Music in Bhaktapur is in the process of establishing a sound archives for Nepalese musical tradi- tions. The department has already published two CDs with Sherpa dance-songs from the Everest region. CD cover: ‘Music of the Sherpa People of Nepal’ (vol.1) published by Eco Himal Little Star Records. Photograph courtesy Gert-Matthias Wegner. Bhucha and betal dancers during a performance in Bhaktapur, 1988. Newar farmers playing bansri and dhimay during Biskit jatra in Bhaktapur. Newar farmers playing bansri and dhimay during Biskit jatra in Bhaktapur. Photographs courtesy Gert- Matthias Wegner. Nepalese Musical Tr a d i t i o n s 233 Until 1951, Nepal had been closed to the rest of the world for s e veral hundred years. The use of the wheel was restricted to ritual purposes. The only school in the country was reserved for members of the ruling Rana aristocracy who pursued a lifestyle similar to the Nawabs of Lucknow. The unique topography of Nepal (with 20 mil- lion inhabitants) helped preserve an extremely rich variety of ethnic g roups (speaking 36 languages) and their musical traditions on a t e rritory half the size of Germany. Despite natural and imposed restrictions on travel, there have been periods of exchange with Indian musical traditions, some of which were modified to local needs and inspired the unique musical culture of the Newar people of the Kathmandu Valley which arguably is the most complex musical tradi- tion in the entire Himalayas.