(This Is a Version of the Published Essay Prior to Copy-Editing and Final Revisions) Rachid Taha and the Postcolonial Presence I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliografia Canterbury Ridotta

Presentazione La scena di Canterbury fu un movimento musicale che si sviluppò tra la fine degli anni Sessanta e la meta dei Settanta nell’omonima cittadina del Kent. Anche se furono molti i gruppi che la composero – alcuni dei quali ancora oggi leggendari come i Soft Machine, i Caravan o i Matching Mole - il numero dei musicisti coinvolti fu sempre molto ridotto, favorendo così un rapporto osmotico tra le varie band anche nelle scelte musicali intraprese. Ciò che caratterizzò la Scena fu infatti una comune idea di arte che possiamo definire – citando Marcus O’Dair, autore della recente biografia di Wyatt – come “un certo stile rock psichedelico venato di jazz, pastorale, very english… con tempi complessi, una preferenza di tastiere rispetto alle chitarre e un modo di cantare convintamente radicato nell’East Kent, là dove i cantanti dell’epoca posavano tutti da Delta bluesman”. Nata con l’album Soft Machine (1968) e conclusa da Rock Bottom (1974) – nonostante i successivi epigoni - la Scena di Canterbury fu sicuramente il momento più alto di tutto il genere Progressive e uno dei movimenti musicali più innovativi (e altrettanto ostici) di tutto il rock. Riascoltato oggi può apparire troppo contorto e scarsamente fruibile, persino nelle sue espressioni più “pop” quali i dischi di Kevin Ayers o dei Caravan, ma in realtà è ancora un’esperienza unica ed entusiasmante per tutti gli ascoltatori disposti a superare le barriere e i tabù che troppo spesso caratterizzano il mondo della musica popolare. Aprile - Maggio 2015 Discografia: Guida all’ascolto Soft machine - Soft machine (1968) Una premessa importante: la Scena di Canterbury fu per sei Soft machine – Two (1969) entusiasmanti anni il fulcro della musica d’avanguardia inglese, Soft machine – Third (1970) proponendo opere spesso di non semplice fruizione che richiedono più Soft machine – Fourth (1971) di un ascolto per essere godute pienamente. -

Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger a Dissertation Submitted

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology by Eric James Schmidt 2018 © Copyright by Eric James Schmidt 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Rhythms of Value: Tuareg Music and Capitalist Reckonings in Niger by Eric James Schmidt Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of California, Los Angeles, 2018 Professor Timothy D. Taylor, Chair This dissertation examines how Tuareg people in Niger use music to reckon with their increasing but incomplete entanglement in global neoliberal capitalism. I argue that a variety of social actors—Tuareg musicians, fans, festival organizers, and government officials, as well as music producers from Europe and North America—have come to regard Tuareg music as a resource by which to realize economic, political, and other social ambitions. Such treatment of culture-as-resource is intimately linked to the global expansion of neoliberal capitalism, which has led individual and collective subjects around the world to take on a more entrepreneurial nature by exploiting representations of their identities for a variety of ends. While Tuareg collective identity has strongly been tied to an economy of pastoralism and caravan trade, the contemporary moment demands a reimagining of what it means to be, and to survive as, Tuareg. Since the 1970s, cycles of drought, entrenched poverty, and periodic conflicts have pushed more and more Tuaregs to pursue wage labor in cities across northwestern Africa or to work as trans- ii Saharan smugglers; meanwhile, tourism expanded from the 1980s into one of the region’s biggest industries by drawing on pastoralist skills while capitalizing on strategic essentialisms of Tuareg culture and identity. -

Natacha Atlas Mish Maoul Mp3, Flac, Wma

Natacha Atlas Mish Maoul mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Pop Album: Mish Maoul Country: UK Released: 2006 Style: Vocal, Ballad MP3 version RAR size: 1860 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1358 mb WMA version RAR size: 1445 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 178 Other Formats: AHX APE MP3 ADX APE MP4 AAC Tracklist Hide Credits Oully Ya Sahbi Bass, Acoustic Guitar, Keyboards, Strings, Programmed By – Dubulah*Cello, Double Bass [Contrabass] – Bernard O'NeillDrums – Brother PDrums, Shaker, Keyboards, Programmed 1 5:33 By – Neil SparkesGoblet Drum [Darabuka] – Ali El MinyawiKeyboards – Natacha AtlasNey, Flute [Kawala] – Louai HenawiVocals – Sofiane SaidiWritten-By – Dubulah*, N. Atlas*, N. Sparkes* Feen Accordion – Gamal El Kordi*Cymbal [Zills], Bells, Shaker, Tambourine, Drums [Duf] – Neil SparkesDouble Bass – Bernard O'NeillGoblet Drum [Darabuka], Drums [Duf] – Ali El 2 MinyawiGuitar, Drums, Keyboards, Arranged By [Strings] – Dubulah*Ney [Solo], Zither 5:46 [Qanun] – Aytouch*Oud – Nizar HusayniRecorded By [Strings] – Khaled Raouf*Strings – The Golden Sounds Studio Orchestra Of CairoVocals – Princess JuliannaWritten-By – Dubulah*, Julie Anne Higgins, N. Atlas*, N. Sparkes* Hayati Inta Backing Vocals – Sofiane SaidiBacking Vocals, Flute [Djouwak], Performer [Tabel], Handclaps, Arranged By – Hamid BenkouiderBacking Vocals, Oud, Lute [Gambri], Drums 3 3:57 [Bendir], Zurna, Percussion [Karkabou], Programmed By, Arranged By – Yazid FentaziDouble Bass – Bernard O'NeillGuitar – Count DubulahProducer – Hamid Benkouider, Natacha Atlas, Philip BagenalWritten-By – M. Eagleton*, N. Atlas* Ghanwah Bossanova Double Bass, Piano – Bernard O'NeillDrums – Brother PDrums, Programmed By, Percussion 4 [Riq], Shaker, Shaker [Shell], Cymbal [Zills], Goblet Drum [Darabuka], Drums [Bendir] – 6:29 Neil SparkesGuitar, Programmed By, Keyboards, Strings – Count DubulahWritten-By – Dubulah*, N. Atlas*, N. -

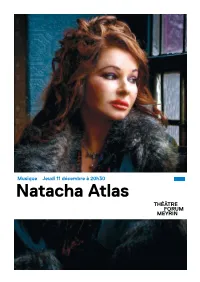

Natacha Atlas

Musique Jeudi 11 décembre à 20h30 Natacha Atlas BaseGVA basedesign.com BaseGVA Photo © Banjee Théâtre Forum Meyrin, Place des Cinq-Continents 1, 1217 Meyrin / +41 22 989 34 34 / forum-meyrin.ch Service culturel Migros, rue du Prince 7, Genève, +41 22 319 61 11 / Stand Info Balexert, Migros Nyon-La Combe Jeudi 11 décembre à 20h30 Natacha Atlas Le concert On dit d’elle qu’elle est la rose raï du Caire. Une Dalida qui aurait emprunté le chemin inverse, l’emmenant des faubourgs de Bruxelles au relatif anonymat de la capitale égyptienne. Natacha Atlas est surtout, depuis une vingtaine d’années, l’incarnation de ce que la world music peut offrir de mieux sur scène, mélangeant des racines orientales, faites de danses du ventre et de youyous hululés, à des rythmes électroniques plus européens, souvenirs de son passage, au début des années 1990, dans le groupe Transglobal Underground. Depuis toujours, elle aime faire le grand écart, construire un pont entre deux rives qu’elle seule semble à même de réunir. Pour sa nouvelle tournée, cette crooneuse des sables s’est entourée d’un aréopage de musiciens issus tout autant du jazz que du folklore arabe. Le résultat est toujours aussi envoûtant, qu’elle entonne le remarquable Rise to Freedom, en hommage à la révolution du Nil de 2011, ou reprenne le joyau qu’est River Man, un titre du compositeur anglais Nick Drake. Natacha Atlas n’aime pas les barrières, encore moins les interdits. Femme du monde, héritière des grandes voix moyen-orientales, on pense à Oum Kalsoum ou à la diva libanaise Fairouz, elle est capable de nous émerveiller avec un concert digne des mille et une nuits étoilées. -

Paris! Le Spectacle

Paris! Le Spectacle Saturday, November 18, 2017 at 8:00pm This is the 775th concert in Koerner Hall Anne Carrère, vocals Stéphanie Impoco, vocals Gregory Benchenafi, vocals Philippe Villa, musical direction & piano Guy Giuliano, accordion Laurent Sarrien, percussion & xylophone Fabrice Bistoni, bass Karine Soucheire, dance Jeff Dubourg, dance PROGRAM Paris medley Paris Les amants d’un jour La bohème Parisienne L'accordéoniste Yves Montand medley La foule Parlez-moi d’amour La goualante du pauvre Jean Comme d’habitude (My Way) J’ai deux amours Y’a d’la Joie medley Mon dieu INTERMISSION Moulin Rouge instrumental French Cancan medley Padam Que reste-t-il de nos amours? Charles Aznavour medley Mon amant de Saint-Jean Ne me quitte pas Jalousie Mon manège à moi Et maintenant Les petites femmes de Pigalle Milord Hymne à l’amour Non, je ne regrette rien La vie en rose Ça c’est Paris Les Champs-Élysées Musical arrangements: Gil Marsalla, Philippe Villa, Arnaud Fustélambezat This spectacular evening is a vibrant tribute to the greatest French songs of the post-war years and exports the charm and the flavour of Paris for the whole world to enjoy. The show transports us from Montmartre to the stages of the great Parisian cabarets of the time, presenting a repertoire of the greatest songs of Édith Piaf, Maurice Chevalier, Lucienne Boyer, Charles Trenet, Josephine Baker, Yves Montand, Charles Aznavour, Jacques Brel, and others. Story: Françoise, a young girl who dreams of becoming a famous artist in Paris, arrives in Montmartre. On her journey, she will cross paths with Édith Piaf and become her friend, confidante, and soul mate. -

Nova Bossa Repertoire

NOVA BOSSA REPERTOIRE JOBIM / BRAZILIAN JAZZ A Felicidade Dindi Agua de Beber Girl from Ipanema Aguas de Março (Waters of March) How Insensitive Amor em Paz (Once I Loved) O Morro Não Tem Vez (Favela) Bonita One Note Samba Brigas Nunca Mais Só Danço Samba Chega de Saudade Triste Corcovado (Quiet Nights) Wave Desafinado BOSSA NOVA / MPB Aquele Um - Djavan Ladeira da Preguiça - Elis Regina A Flor e o Espinho - Leny Andrade Lobo Bobo - João Gilberto Aquarela do Brasil (Brazil) - João Gilberto Maçã do Rosto - Djavan (Forró) A Rã - João Donato Mas Que Nada - Sergio Mendes Bala Com Bala - Elis Regina Maria das Mercedes - Djavan Berimbau - Baden Powell O Bêbado e a Equilibrista - Elis Regina Capim - Djavan O Mestre Sala dos Mares - Elis Regina Chove Chuva - Sergio Mendes O Pato - João Gilberto Casa Forte - Elis Regina (baião) Reza - Elis Regina Doralice - João Gilberto Rio - Leny Andrade É Com Esse Que Eu Vou - Elis Regina Serrado - Djavan Embola Bola - Djavan Telefone - Nara Leão Estate (Summer) - João Gilberto Tristeza - Beth Carvalho Fato Consumado - Djavan Vatapá - Rosa Passos Flor de Lis - Djavan Você Abusou JAZZ STANDARDS A Night in Tunisia Don't Get Around Much Anymore All of Me Fly Me To The Moon Almost Like Being in Love Gee, Baby, Ain't I Good to You As Time Goes By Green Dolphin Street Brother Can You Spare A Dime? Honeysuckle Rose Bye Bye Blackbird How High the Moon C'est Si Bon How Long Has This Been Going On? Dearly Beloved I Could Write A Book Do Nothing Til You Hear from Me I Only Have Eyes for You 1 I Remember You Save Your -

E:\Volume2.CD-Rom\6.Conjunto Global Dos Textos Em Formato .Txt

txt2/textos_dos_jornais_portugueses-Correio-10_janeiro-opinião2.10_jan.doc.txt O valor das palavras No último Mundial de Futebol ficámos a conhecer a vuvuzela, uma espécie de corneta com um som entre a sirene e o elefante que é capaz de despertar no monge o espírito de um taliban. Em 2010, 'vuvuzela' foi a nossa palavra do ano, e se dúvidas existiam, confirmámos então que é mais fácil recordar o que pior nos faz. No ano anterior, 2009, graças a Ricardo Araújo Pereira & Cia, é certo, mas, particularmente, às eleições e aos políticos que tínhamos (e ainda temos), ganhou 'esmiuçar', "vocábulo utilizado quando se pretende examinar algo minuciosamente, reduzir a fragmentos, a pó, a esmigalhar ou a esfarelar", segundo o dicionário. Em 25 minutos, na TV, com 'Gato Fedorento esmiuça os sufrágios', este país de poetas passou a saber o valor da palavra referida. Passada a vontade de esmiuçá-los e de esmiuçarmo-nos, e pontapeados pela semântica da economia, elegemos 'austeridade' para 2011. Bateu 'esperança' e até 'troika' e nem a certeza de que já estão a vir 'charters' vingou. Austeridade é "a qualidade de quem é austero"; é "severidade e rigor"; "cuidado escrupuloso em não se deixar dominar pelo que agrada aos sentidos ou deleita a concupiscência". E está tudo dito. Fernanda Cachão * Editora de CORREIO DOMINGO txt2/textos_dos_jornais_portugueses-Correio-10_janeiro-Entrevista.10jan.doc.txt Sandra Cóias confessa não ser mulher de fazer planos para o futuro. A actriz, que diz preferir fazer séries ou cinema, está a aproveitar o fim das gravações de 'Pai à Força' (RTP 1) para participar em castings "Ritmo das novelas não me agrada" – Que projectos tem em mãos neste momento? – Fui a um casting para televisão mas não posso falar sobre o assunto. -

Canal Du Midi Waterways Guide

V O L 2 . 1 F R E E D O W N L O A D discover Sharing our love for France's spectacular waterways R U H T R A C M D © L I E L O S I O R Canal du Midi E G Pink cities, Cathar histories, impossibly low bridges, R A UNESCO status, medieval wonders, Corbières & Cremant B L E T O H P A G E 2 Canal du Midi YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO FRANCE'S MOST POPULAR WATERWAY Introducing the Canal du Midi Canal du Midi essentials Why visit the Canal du Midi? Where's best to stop? How to cruise the Canal du Midi? When to go? Canal du Midi top tips Contact us Travelling the magical Canal du Midi is a truly enchanting experience that will stay with you forever. It’s a journey whose every turn brings spectacular beauty that will leave you breathless. It’s an amazing feat of engineering whose elegant ingenuity will enthral you. It’s a rich and fertile region known for superb local produce, fabulous cuisine and world class wine. So, no matter how you choose to explore the Canal du Midi, by self-drive boat or hotel barge, just make sure you’re prepared to be utterly enchanted. Ruth & the team H O T E L B A R G E S A R A P H I N A P A G E 3 INTRODUCING THE CANAL DU MIDI The Canal du Midi runs from the city of Toulouse to It was the Romans who first dreamt of connecting the Mediterranean town of Sète 240km away. -

La Musique Francophone Objectifs

La musique francophone Objectifs Présenter un chanteur Biographie – pays Présenter une chanson ou un clip Le théme – l’histoire – le message Mon avis Mon avis sur le chanteur et la chanson Ma musique Programme Khaled – Aïcha - Le Raï Qu’est-ce que tu aimes comme musique? Pour toi qu’est-ce que c’est la musique? Khaled Khaled est né à Oran en Algérie. L'Algérie est un pays en Afrique du Nord entre le Maroc et la Tunisie. Khaled est né en 1960. Il devient musicien à l'âge de 7 ans. Il chante le Raï. Il a beaucoup de succès. En 1985, il participe au festival du Raï à Oran. Il est sacré " Roi du Raï " par le public. En 1996, Jean-Jacques Goldman écrit la chanson "Aicha" pour Khaled ". Cette chanson a un succès international et elle est élue meilleure chanson de l’année aux "Victoires de la musique ". La chanson "Aïcha" est sur l'album qui s'appelle Sahra. Les chanteurs et leur chanson 1. Zaz – Je veux 2. Faudel – Je veux vivre 3. Jocelyne Labylle – J’ai déposé les clefs 4. African connection – Ami oh! 5. Alpha Blondy – Journaliste en danger 6. Calogero et Passi – Face à la mer 7. Pham Quynh Anh – Bonjour vietnam 8. Tiken Jah Fakoly - Un africain à Paris 9. Diam’s – Jeune demoiselle 10. Amel Bent – Ma philosophie Zaz – Je veux Isabelle Geffroy, alias Zaz, est née à Tours en 1980. Son style musical est un mélange de jazz manouche, de soul et d'acoustique. Zaz commence sa carrière musicale à Paris dans les rues, les cafés, et les cabarets. -

A Gergely András: „Arab”

A.GERGELY ANDRÁS „ARAB” VILÁGZENE, AVAGY A RAÏ ZENEI SZCÉNÁJA (2/1.) A legkevésbé sem erőltethető, hogy a Parlando hasábjain bármily érdeklődési eltolódás következzen be a kortárs zenei műfajok, irányzatok vagy akár kultuszok területén. Ám abban a lehetséges bűvkörben, ahol a világ népeinek, kultúráinak, ezek keveredéseinek vagy konfliktusainak, az átvételek, divatok, kölcsönhatások rendszerének új jelenségeire is odafigyelhetünk, nem kevéssé érdemes észrevenni kultúrák, kultuszok és zenei beszédmódok között annak a műfaji jelenségnek születését és hatását, melyet a raï zenei világának nevezhetünk. Kérdés: érdemes-e itt valamiféle „ezoterikus” tüneményről elmélkedni? Kell-e egy bizonyos ideig tartó, de rövid korszaknál (újdonságerejénél fogva ugyan ható, ugyanakkor) nem zenetörténeti jelenségről ott szólani, ahol időt állóbbnak nevezhető alaptónus az uralkodó? Kell-e, s lehet- e a 21. század zenéjében föl-fölbukkanó hatásokra méltóképpen fölfigyelni, vagy megmarad mindez a divatkedvelők időleges horizontján valami alkalmi jelenségként, időleges folyamatként, esetleges szereplők tereként? S ha analógiákat keresünk: Bartók török gyűjtése, az amerikai zenei kultúra country- hagyományai, az indiai zenék évtizedeket átható fogyasztási kultúrája Európában, vagy akár a balkáni cigány népzene belopakodása a kortárs zenei gondolkodásba, vajon érdemi zenetudományi kérdésfeltevésekre is alkalmassá válik-e, kellő hatásuk pedig zenepedagógiai érdeklődésre is számot tarthat-e? Vagy, mindezek mellett és helyett, pusztán egy divatkorszak divatos zenéjéről van szó a raï esetében, mely érkezett is, múlik is, ezért legyinthetünk rá…? A megfontolásokat két dimenzióban próbálom tárgyalni. Először egy ismeretközlő, „népszerűsítő” áttekintés, publicisztikus mű ismertetésével, majd második körben egy térségi zenei övezet korszakos sodrásával igyekszem bemutatni egy szórakoztató (de nemcsak), divatos (de annál tradicionálisabb), térségi-tájegységi (ám akként a Mediterránum szinte egészét átható, Európa nyugati felén is széles sávban hódító) zenei jelenség mibenlétét. -

Lindsay Cooper: Bassoonist with Henry Cow Advanced Search Article Archive Topics Who Who Went on to Write Film Music 100 NOW TRENDING

THE INDEPENDENT MONDAY 22 SEPTEMBER 2014 Apps eBooks ijobs Dating Shop Sign in Register NEWS VIDEO PEOPLE VOICES SPORT TECH LIFE PROPERTY ARTS + ENTS TRAVEL MONEY INDYBEST STUDENT OFFERS UK World Business People Science Environment Media Technology Education Images Obituaries Diary Corrections Newsletter Appeals News Obituaries Search The Independent Lindsay Cooper: Bassoonist with Henry Cow Advanced search Article archive Topics who who went on to write film music 100 NOW TRENDING 1 Schadenfreudegasm The u ltim ate lis t o f M an ch ester -JW j » United internet jokes a : "W z The meaning of life J§ according to Virginia Woolf 3 Labour's promises and their m h azard s * 4 The Seth Rogen North Korea . V; / film tra ile r yo u secretly w a n t to w atch 5 No, Qatar has not been stripped o f th e W orld Cup Most Shared Most Viewed Most Commented Rihanna 'nude photos' claims emerge on 4Chan as hacking scandal continues Frank Lampard equalises for Manchester City against Her Cold War song cycle ‘ Oh Moscow’ , written with Sally Potter, was performed Chelsea: how Twitter reacted round the world Stamford Hill council removes 'unacceptable' posters telling PIERRE PERRONE Friday 04 October 2013 women which side of the road to walk down # TWEET m SHARE Shares: 51 Kim Kardashian 'nude photos' leaked on 4chan weeks after Jennifer Lawrence scandal In the belated rush to celebrate the 40 th anniversary of Virgin Records there has been a tendency to forget the groundbreaking Hitler’s former food taster acts who were signed to Richard Branson’s label in the mid- reveals the horrors of the W olf s Lair 1970s. -

Energy Security: Implications for U.S.-China-Middle East Relations

The James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy of Rice University Energy Security: Implications for U.S.-China-Middle East Relations Is there an Arab Popular Culture? Susan Ossman Department of Anthropology, Rice University Prepared in conjunction with an energy conference sponsored by The Shanghai Institute for International Studies and The James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy Rice University - July 18, 2005 This program was made possible through the generous support of Baker Botts L.L.P. THESE PAPERS WERE WRITTEN BY A RESEARCHER (OR RESEARCHERS) WHO PARTICIPATED IN A BAKER INSTITUTE RESEARCH PROJECT. WHEREVER FEASIBLE, THESE PAPERS ARE REVIEWED BY OUTSIDE EXPERTS BEFORE THEY ARE RELEASED. HOWEVER, THE RESEARCH AND VIEWS EXPRESSED IN THESE PAPERS ARE THOSE OF THE INDIVIDUAL RESEARCHER(S), AND DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT THE VIEWS OF THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY. © 2004 BY THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY OF RICE UNIVERSITY THIS MATERIAL MAY BE QUOTED OR REPRODUCED WITHOUT PRIOR PERMISSION, PROVIDED APPROPRIATE CREDIT IS GIVEN TO THE AUTHOR AND THE JAMES A. BAKER III INSTITUTE FOR PUBLIC POLICY. Is there an Arab Popular Culture? A great deal of attention has been given in recent years to the way that Arab satellite television has emerged as a transnational political force. But very new commentators have bothered to study how this news is being received, how it shapes a nebulous "Arab" world or Arab community, and especially, to the fact that most of what is projected on satellite television is not news at all. From the beginning, soap operas, talk shows, music videos and serials have dominated most satellite programming.