Oral History Interview with Reuben Kadish, 1964 Oct. 22

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jackson Pollock & Tony Smith Sculpture

Jackson Pollock & Tony Smith Sculpture An exhibition on the centennial of their births MATTHEW MARKS GALLERY Jackson Pollock & Tony Smith Speculations in Form Eileen Costello In the summer of 1956, Jackson Pollock was in the final descent of a downward spiral. Depression and alcoholism had tormented him for the greater part of his life, but after a period of relative sobriety, he was drinking heavily again. His famously intolerable behavior when drunk had alienated both friends and colleagues, and his marriage to Lee Krasner had begun to deteriorate. Frustrated with Betty Parsons’s intermittent ability to sell his paintings, he had left her in 1952 for Sidney Janis, believing that Janis would prove a better salesperson. Still, he and Krasner continued to struggle financially. His physical health was also beginning to decline. He had recently survived several drunk- driving accidents, and in June of 1954 he broke his ankle while roughhousing with Willem de Kooning. Eight months later, he broke it again. The fracture was painful and left him immobilized for months. In 1947, with the debut of his classic drip-pour paintings, Pollock had changed the direction of Western painting, and he quickly gained international praise and recog- nition. Four years later, critics expressed great disappointment with his black-and-white series, in which he reintroduced figuration. The work he produced in 1953 was thought to be inconsistent and without focus. For some, it appeared that Pollock had reached a point of physical and creative exhaustion. He painted little between 1954 and ’55, and by the summer of ’56 his artistic productivity had virtually ground to a halt. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 13 American Artists: a Celebration Of

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: 13 American Artists: A Celebration of Historic Work April 29 - June 26, 2021 Eric Firestone Gallery 40 Great Jones Street |New York, NY Featuring work by: Elaine Lustig Cohen |Charles DuBack | Martha Edelheit | Shirley Gorelick Mimi Gross | Howard Kanovitz | Jay Milder | Daphne Mumford | Joe Overstreet | Pat Passlof | Reuben Kadish | Miriam Schapiro | Thomas Sills Charles Duback | Adam and Eve, 1970 |acrylic, wood and felt on canvas | 96h x 120w in In honor of our first season in a new ground floor space at 40 Great Jones Street, Eric Firestone Gallery presents 13 American Artists, an exhibition showcasing artists from the gallery’s unique, wide-ranging historical program. The gallery has made central a mission to explore the ever-expanding canon of Post-World War II American art. Over the last several years, the gallery has presented major retrospectives to champion artists whose stories needed to be re-told. Their significant contributions to art history have been further reinforced by recent institutional acquisitions and exhibitions. 13 American Artists celebrates this ongoing endeavor, and the new gallery, presenting several artists and estates for the first time in our New York City location. EAST HAMPTON NYC 4 NEWTOWN LANE 40 GREAT JONES STREET EAST HAMPTON, NY 11937 NEW YORK, NY10012 631.604.2386 646.998.3727 Shirley Gorelick (1924-2000) is known for her humanist paintings of subjects who have traditionally not been heroized in large-scale portraiture. Gorelick, like most artists in this exhibition, forged her career outside of the mainstream art world. She was a founding member of Central Hall Artists Gallery, an all-women artist-run gallery in Port Washington, New York, and between 1975 and 1986, had six solo exhibitions at the New York City feminist cooperative SOHO20. -

Oral History Interview with Reuben Kadish

Oral history interview with Reuben Kadish Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 2 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... Oral history interview with Reuben Kadish AAA.kadish92 Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: Oral history interview with Reuben Kadish Identifier: AAA.kadish92 Date: 1992 Apr. 15 Creator: Kadish, Reuben, 1913-1992 (Interviewee) Polcari, Stephen (Interviewer) Extent: 1 Sound cassette (Sound recording) 40 Pages (Transcript) Language: English . Digital Digital Content: Oral history interview with Reuben Kadish, 1992 -

Mural Decorations - Completed and in Progress - by Federal Art Project in Northern Southern California April 1, 1937

Mural Decorations - Completed and in Progress - by Federal Art Project in Northern Southern California April 1, 1937 Area Institution Location City Name Medium Status S John C. Fremont School Anaheim Arthur Ames 2 panels oil on gesso Completed S Beaumont District Library Beaumont Henri De Kruif 2 panels oil on canvas Completed N Belvedere Public Library Selden G. Gile 3 x 12 ft decorative panel, oil Completed Belvedere 8 x 22 ft carved redwood N California School for the Blind Berkeley Sargent Johnson Completed panel low relief University of California - N UC Art Gallery, East Façade Berkeley Florence Swift tile mosaic Completed Berkeley University of California - N UC Art Gallery Berkeley Florence Swift glazed tile decorations In Progress Berkeley University of California - N UC Art Gallery, East Façade Berkeley Helen Bruton tile mosaic Completed Berkeley University of California - N UC Art Gallery Berkeley Helen Bruton glazed tile decorations In Progress Berkeley S Beverly Hills High School Music Room Beverly Hills P.G. Napolitano fresco panel In Progress N Sunset Grammar School Carmel Armin Hansen oil on canvas mural Completed Los Angeles Tubercular Phillip Goldstein and Reuben S Library Duarte fresco panel Completed Sanatorium Kadish S East Whittier Primary School Cafeteria East Whittier Caspar Duchow glazed tile mosaic Completed S El Monte Public Library El Monte R.W.R. Taylor 11 panels fresco on celotex In Progress S Mountain View School Wall Fountains El Monte Bessie Heller 2 panels glazed tile mosaic In Progress Frank H. Bowers and Arthur S Ruth School El Monte 2000 sq ft fresco In Progress W. -

Complete History

The Hotel Albert 23 East 10th Street, NYC Hotel Albert c.1907 Photograph obtained from The Museum of the City of New York A History Prepared by Anthony W. Robins Thompson & Columbus, Inc. April 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................. 3 PART I: Construction History ........................................................................................ 5 PART II: Descriptions of the Hotel St. Stephen Prior to its Incorporation into the Hotel Albert .................................................................................................... 15 PART III: The Early Years Up To World War I – Descriptions and Visitors ......... 19 PART IV: The Early Years Up To World War I – Resident Writers and Artists ... 30 PART V: From the 1920s Through World War II and Just Afterwards .................. 43 PART VI: From the 1920s Through World War II and Afterward: Writers, Artists and Radicals ................................................................................................... 46 PART VII: 1950s and 1960s – Writers, Artists, Actors And Descriptions Of The Hotel .............................................................................................................. 61 PART VIII: The Albert French Restaurant ................................................................. 69 PART IX: 1960s Musicians ............................................................................................ 89 PART X: End of an Era .............................................................................................. -

Jules Langsner Papers, 1941-1967

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5v19r00h No online items Finding Aid for the Jules Langsner papers, 1941-1967 Processed by UCLA Library Special Collections staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Caroline Cubé. UCLA Library Special Collections Room A1713, Charles E. Young Research Library Box 951575 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1575 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.library.ucla.edu/libraries/special/scweb/ © 2007 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid for the Jules Langsner 1748 1 papers, 1941-1967 Descriptive Summary Title: Jules Langsner papers Date (inclusive): 1941-1967 Collection number: 1748 Creator: Jules Langsner, 1911-1967. Extent: 26 boxes (13 linear feet)1 oversize box. Abstract: Jules Langsner was born on May 5, 1911, in New York, New York and died in Los Angeles, California, on September 29, 1967. Langsner was surrounded by intellectuals and artists from a young age, and became a celebrated art writer, critic and curator. The collection consists of correspondence, manuscripts, ephemera, and photographs related to Langsner's writing, research and curatorial work. Language: English Repository: University of California, Los Angeles. Library Special Collections. Los Angeles, California 90095-1575 Physical location: Stored off-site at SRLF. Advance notice is required for access to the collection. Please contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Access COLLECTION STORED OFF-SITE AT SRLF: Open for research. Advance notice required for access. Contact the UCLA Library Special Collections Reference Desk for paging information. Restrictions on Use and Reproduction Property rights to the physical object belong to the UCLA Library Special Collections. -

Work and Play: a Case Study of Philip Guston

Work and Play A Case Study of Philip Guston ● The Great Depression left the nation in a desperate state. 1929-1939 ❖ Unemployment rates soaring, savings lost, the banks collapsed, homes lost, and hunger ravaging the nation ● President Franklin D. Roosevelt established a federally funded program in efforts to help end the crisis by creating and providing new jobs. The WPA (Works Progress Administration) Maintaining America’s Skills. Philip Guston, Mural- New York World’s Fair WPA building, 1939-1940. Youths gathering scrap metals near factory sites in Long Island City, Circa Image Credit New York Public Library Archives. 1939. Image credit New York Public Library Archives. Philip Guston an American artist and a product of the Great Depression/WPA Philip Guston timeline 1930: Otis Art Institute, L.A. 1934: Guston & Reuben set to work for first federally funded art Meet Reuben Kadish project in California (the Civil Works Administration Arts Projects). 1927: Manual Arts High Artists kicked off project by administration, got into a quarrel. 1980: Died Born: June 27, 1913 School in L.A. 1935-1936: Moved to NYC. June 7. Montreal, Canada Woodstock, Joined WPA mural art division. N.Y. 1919: Moved to L.A. 1929: Expelled from school with friend 1939: Mural “Maintaining America’s California, Age 6 Jackson Pollock, For disorderly behavior & drawing cartoons that Skills” for WPA building, World’s Fair. ridiculed the academic program Mural “Work and Play” Queensbridge housing, under WPA 1910 1920 1930 1940 1980 1932: November Franklin D. Roosevelt won presidential elections 1939:Sept. 1 1945: Sept. 2 1918: November 11 WWII WWII ended WWI ended 1929: October 29, Stock market crashed. -

![[Photographs of Reuben Kadish, Philip Guston, and Others]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9860/photographs-of-reuben-kadish-philip-guston-and-others-2609860.webp)

[Photographs of Reuben Kadish, Philip Guston, and Others]

[Photographs of Reuben Kadish, Philip Guston, and others] Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 1 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 1 Container Listing ...................................................................................................... [Photographs of Reuben Kadish, Philip Guston, and others] AAA.kadireup Collection Overview Repository: Archives of American Art Title: [Photographs of Reuben Kadish, Philip Guston, and others] Identifier: AAA.kadireup Date: 1934-1965 Creator: Kadish, Reuben, 1913-1992 Extent: 8 Items (photographic prints; b&w; 10 x 8 in. and smaller. (reel 5660)) Language: English . Administrative Information Acquisition Information Donated 1984 by Reuben Kadish. Restrictions Use of original papers requires an appointment and is limited to the Archives' Washington, D.C., Research Center. -

Reuben Kadish and His Work

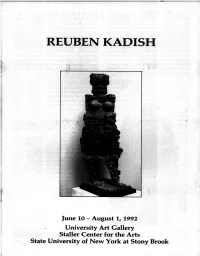

' REUBEN KADISH • June 10 - August 1, 1992 University Art Gallery Staller Center for the Arts I State University of New York at Stony Brook I CURATOR'S NOTE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Without the dedicated, knowledgable, and sensi I would like to express my gratitude to guest tive help of sculptor Jenny Lee and painter Hilda curator Mel Pekarsky, painter and Professor of O'Connell, this exhibition would not have been Art at the State University of New York at possible, and I want to thank them. Herman Stony Brook, for curating this exhibition. Thanks Cherry, Reub's good friend, a poet of a painter, are also due to Jenny Lee, Hilda O'Connell, and and a wonderful man, would have added to his Douglas Still, Registrar, and the staff of Grace statement, but couldn't, owing to failing health; Borgenicht Gallery for their assistance with the he passed away earlier this year. To Dore Ash organization of this exhibition. ton, universally renowned and respected for her I also want to thank Dore Ashton for contri work on a generation of feisty artists that buting the insightful essay published in this cata changed art in America and the world, I express logue. I am also grateful to Herman Cherry who my personal thanks for a deeply felt and moving gave us permission to reprint his essay on appreciation of Reuben Kadish and his work. Reuben Kadish in our catalogue. Special thanks are also extended to members of Mel Pekarsky the Staller Center for the Arts staff: Heejung May, 1992 Kim and Amy Schichtel, Curatorial Assistants; Ann Bomberger, Brenda Hanegan, Julie Larson, Michael Parke, and Christina Ridenhour, Gallery Assistants; David Buckle, Jisook Kwon, and Roseann Stewart, Gallery Interns; Patrick Kelly, Liz Stein, and the Technical Crew, Staller Center for the Arts, for exhibition lighting; and Mary Balduf, Gallery Secretary. -

The Brooklyn Rail

ArtSeen November 5th, 2010 by James Kalm With the harmonies of Jan and Dean and the Beach Boys pouring out of every car radio, as a kid growing up in the West during the ’60s, I didn’t have to be reminded that California was where it was happening. I ran away from home the day summer vacation started after my junior year of high school, and hitched to San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district to spend a month getting a firsthand introduction to West Coast hipness. To us back then, the Continental Divide wasn’t just a ridge that dictated whether a river would run east or west but was also an aesthetic division. A rock ’n’ roll analogy would be West Coast bands like Jefferson Airplane, Big Brother and the Holding Company, and the Doors versus New York’s doo-wop-derived Frankie Valli and the Four Seasons or folk-based performers like Bob Dylan or Simon and Garfunkel. However, when it came time to fly the coop and pick a coast to pursue an artistic “career,” even though Bay Area Funk Art and Finish Fetish seemed more approachable, sexy, and fun than the buttoned-down formalism of Minimalism and Conceptual Art that we were reading about in Artforum and Art in America, New York seemed the only logical choice. Memories of this long ago decision came surging back during a recent visit to Los Angeles. Art history geek that I am, I dragged Kate and our son Mac on a pilgrimage to 723 North La Cienega Boulevard, the location of the legendary Ferus Gallery. -

Reuben Kadish, 7O, a Sculptor of Works Evoking the Ancient

G.4. Einstein Comtanyjnc. THE NEW YORK TIMES OBITUARIES TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 22, 1992 Reuben Kadish, 7o, a Sculptor Of Works Evoking the Ancient BY ROBERTA SMITH Reuben Keats, an Ameritan sculp- of ancient Mexico made an tor whose rough-hewn figures and =Ire impression on him, as did the monumental brads often evoked the sculpture of India, which he encoun- art of ancient civilizations, died on Sun- tered while working in$ Asia in the day at New York Hospital In Manhat- Army Artist Unit in the last two years tan. He was 79 jean old and had homes of World War II. In Manhattan and Vernon, N.J. After the war, he moved to New York He died of complications from citron City. In 1948, to support his family, he 1c leukemia, said his son Julian. bought a dairy farm In Vernon, which he operated for 10 years. During this Mr. Kadish, Mho was born in Ch lcagoi period, he stopped painting and eventu- on Jan. 29, 1913, and reared in Los ally took up sculpture. In 1961, he had Angeles, started his career as a paint- his first one-man show in New York er, studying with the West Coast paint- City and began teaching art at Cooper er Loner Felt,Ism while sUll a teen- Union, which he continued up to a few ager. While &standing the Otis MI Insti- months ago. He was represented since tute in Los Angeles, he formed close Ire by the Grace Borgenicht Gallery friendships with Jackson Pollock and In Manhattan. Pbflip Gustort, who would become Ab- His. -

Biography • Philip Guston Philip Guston • Biography

BIOGRAPHY • PHILIP GUSTON PHILIP GUSTON • BIOGRAPHY 1913 Born Phillip Goldstein, June 27 in Montreal, to Louis and Rachel Goldstein, both of whom were immigrants from Odessa, Russia. Philip Guston is the youngest of seven children. 1919 Family moves to Los Angeles. 1923 Father commits suicide. 1926 Youthful aptitude for drawing leads Guston's mother to enroll him in a correspond- ence course from Cleveland School of Cartooning, Cleveland, Ohio. 1927 Attends Manual Arts High School in Los Angeles, where he meets and develops a friendship with Jackson Pollock, Manuel Tolegian and Reuben Kadish. 1930 Wins a scholarship to attend Otis Art Institute, Los Angeles, where he meets Musa McKim, but leaves the Institute after three months. Studies painting at home and works as an occasional extra in several movies. Sees Modern European painting in the collection of Walter and Louise Arensberg and first encounters the work of de Chirico. 1931 First solo exhibition at the Stanley Rose Bookshop and Gallery, Hollywood, organ- ised by the painter, Herman Cherry. 1932 Visits Pomona College, Claremont, California, with Pollock to see José Clemente Orozco at work on his mural “Prometheus.” 1933 Exhibits “Mother and Child,” 1930, Guston's first fully developed painting, at the 14th Annual Exhibition at the Los Angeles Municipal Museum. 1934 Travels to Mexico with Reuben Kadish and poet Jules Langsner. Paints the huge mural "The Struggle Against War and Facism" with Kadish, which still stands in the Museo de Michoacan, Morelia, Mexico. Completes commission with Kadish for the City of Hope Tuberculosis Sanatorium of the ILGWA, Duarte, California. 1936 Moves to New York City.