Sebald Beham & Barthel Beham

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Observing Protest from a Place

VISUAL AND MATERIAL CULTURE, 1300-1700 Knox Giles Knox Sense Knowledge and the Challenge of Italian Renaissance Art El Greco, Velázquez, Rembrandt of Italian Renaissance Art Challenge the Knowledge Sense and FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Sense Knowledge and the Challenge of Italian Renaissance Art FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 A forum for innovative research on the role of images and objects in the late medieval and early modern periods, Visual and Material Culture, 1300–1700 publishes monographs and essay collections that combine rigorous investigation with critical inquiry to present new narratives on a wide range of topics, from traditional arts to seemingly ordinary things. Recognizing the fluidity of images, objects, and ideas, this series fosters cross-cultural as well as multi-disciplinary exploration. We consider proposals from across the spectrum of analytic approaches and methodologies. Series Editor Dr. Allison Levy, an art historian, has written and/or edited three scholarly books, and she has been the recipient of numerous grants and awards, from the Nation- al Endowment for the Humanities, the American Association of University Wom- en, the Getty Research Institute, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library of Harvard University, the Whiting Foundation and the Bogliasco Foundation, among others. www.allisonlevy.com. FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS Sense Knowledge and the Challenge of Italian Renaissance Art El Greco, Velázquez, Rembrandt Giles Knox Amsterdam University Press FOR PRIVATE AND NON-COMMERCIAL USE AMSTERDAM UNIVERSITY PRESS This book was published with support from the Office of the Vice Provost for Research, Indiana University, and the Department of Art History, Indiana University. -

Bavaria: Statistics 2020

Bavaria: Statistics 2020 www.statistik.bayern.de Publication service The avarian State Office for Statistics issues more than 400 publications annually. The current list of publications is available on the Internet as a file but can also be provided free of charge in printed form. Free of charge Publication service is the download of most publications, All publications are available e. g. statistical reports (PDF or Excel format). on the Internet at www.statistik.bayern.de/produkte Subject to charge are all print versions (also of statistical reports), data carriers and selected files (e. g. of directories, of contributions, of the yearbook). Explanation of symbols Rounding 0 less than half of 1 in the last digit occupied, In general totals have been rounded and therefore but more than zero may not sum. As a result minor deviations from the – no figures or magnitude ero reported totals may occur when individual figures are / no data because the numerical value is not added up. When totals are shown as a percentage, sufficiently reliable the sum of the individual figures may not be 100 due to rounding. In general the sum of percentages is not · numerical value unknown or not to be disclosed made to be 100 . ... data will be available later x cell blocked for logical reasons Abbreviations ( ) limited informational value because the numerical value is of limited statistical reliability € euro p provisional numerical value EU European Union r corrected numerical value ALC association of local councils s estimated numerical value ha hectare (10,000 m2) D average hl hectolitres (100 litres) ‡ corresponds to mill. -

Here Is the Title the Subtitle to Content

Briefing: Bavaria & Munich’s Economic and Cultural Assets Denver Leadership Exchange, October 2017 Page Introduction to Bavaria A short film https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-rckHpEUnKg Page Quick Facts Munich vs. Denver Population Population ▪ City of Munich: 1.5 mn ▪ City of Denver: 700,000 ▪ Metro Munich: 2.9 mn ▪ Metro Denver: 2.8 mn Important Industries Important Industries ▪ Automotive/Mobility ▪ Aerospace/Aviation ▪ Construction/Engineering ▪ Health/MedTech/Pharma ▪ Creative Industries ▪ Energy/Cleantech Median Income: € 47,868 Median Income: $60,260 Favorite Sports Team: Favorite Sports Team: Favorite Drink: Favorite Drink: Page Bavaria & Munich your ideal location for growth in EMEA Key Success Factor #1: Strong economy in the heart of the EU Key Success Factor #2: Powerful and diverse company landscape Key Success Factor #3: Europe’s leading innovation hub Key Success Factor #4: Supportive government and politics Key Success Factor #5: High quality of living Page #1 Strong economy in the heart of Europe Bavaria at a glance Hamburg Berlin Hanover Düsseldorf Erfurt Dresden Frankfurt 27,200 sqm € 568 bn Germany‘s largest Federal State Nuremberg GDP (2016) / #7 in EU 12.8 mn Stuttgart 14.7% Munich inhabitants (16% of Germany) growth (2010 to 2016) 3.5% € 183 bn unemployment (2016) export volume (2016) Page #1 Strong economy in the heart of Europe In the center of Europe Helsinki Well connected to 500 mn Oslo Stockholm customers within the EU Riga Dublin Kiev London Warsaw Brussels Paris Munich Budapest 1h Zurich Vienna Bucharest 2h -

Renaissance Drawings from Germany and Switzerland, 1470-1600 March 27 to June 17, 2012 the J

Renaissance Drawings from Germany and Switzerland, 1470-1600 March 27 to June 17, 2012 The J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center 5 5 1. Upper Rhenish Master 2. Martin Schongauer German, active about 1470 - 1490 German, about 1450/1453 - 1491 GERM GERM AN AN AND AND Christ as Gardener, About 1470-90 Peonies, About 1473 Pen and gray black ink Gouache and waterolor 24.1 x 10.8 cm (9 1/2 x 4 1/4 in.) 25.7 x 33 cm (10 1/8 x 13 in.) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles 2003.11 92.GC.80 5 5 3. After The Master of the Housebook 4. Unknown maker, German, 15th century GERM AN German, active about 1470 - 1500 AND Mary Magdelene with Angels, About 1490 GERM AN AND Courtly Scenes, About 1475-90 Pen and black ink with white gouache highlights on Pen and black ink reddish-brown grounded paper 24.1 x 21.7 cm (9 1/2 x 8 9/16 in.) 17 x 16.2 cm (6 11/16 x 6 3/8 in.) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles 2005.39 83.GG.355 March 14, 2012 Page 1 of 8 Additional information about some of these works of art can be found by searching getty.edu at http://www.getty.edu/art/gettyguide/ © 2012 J. Paul Getty Trust 5 5 recto and 5. Master of the Coburg Roundels 6. Mair von Landshut German, active about 1470 - 1500 German, about 1450 - 1504 GERM GERM AN AN AND Christ's Loincloth (Recto); Bookbinding and Christ's AND Angel, 1498 Loincloth (Verso), About 1490 Black ink and white tempera highlights on gray prepared Pen and brown and black ink, brown and gray wash paper (recto); pen and brown and black ink, brown and gray 12.4 x 9.5 cm (4 7/8 x 3 3/4 in.) wash, heightened with white gouache (verso) The J. -

Familien Fragebogen

Familien Fragebogen Diese Befragung wird zur Erstellung der ersten Kinder- und Familien-Freizeitkarte für unsere Region am Bayerischen Untermain durchgeführt. Die Ergebnisse kommen als Freizeittipps in den Plan. Bitte die ganze Familie gemeinsam ausfüllen. Wir wohnen in der Stadt/Gemeinde: ____________________________________ 1. Der beste Spielplatz in unserer Gegend (im Ort oder Umgebung) ist… __________________________________________________ (Ort/Ortsteil + Straße) Begründung: _________________________________________________________ Der zweitbeste Spielplatz in unserer Gegend (im Ort oder Umgebung) ist… __________________________________________________ (Ort/Ortsteil + Straße) Begründung: _________________________________________________________ 2. Außer auf offiziellen Spielplätzen spielen wir gerne dort...(Bitte genaue Ortsan- gabe und auf der beigefügten Karte markieren - am besten mit Nummer versehen) Wiese zum Drachensteigen: ____________________________________________ Wiese zum (Ball)spielen: _______________________________________________ Picknick-Wiese: ______________________________________________________ Rodelhang: __________________________________________________________ Wassertreffpunkt (bespielbare Brunnen, Bäche…): ___________________________ ___________________________________________________________________ Skaten: _____________________________________________________________ Spielort im Wald: _____________________________________________________ -

The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth

The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Adam R. Gustafson June 2011 © 2011 Adam R. Gustafson All Rights Reserved 2 This dissertation titled The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria by ADAM R. GUSTAFSON has been approved for the School of Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts _______________________________________________ Dora Wilson Professor of Music _______________________________________________ Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT GUSTAFSON, ADAM R., Ph.D., June 2011, Interdisciplinary Arts The Artistic Patronage of Albrecht V and the Creation of Catholic Identity in Sixteenth- Century Bavaria Director of Dissertation: Dora Wilson Drawing from a number of artistic media, this dissertation is an interdisciplinary approach for understanding how artworks created under the patronage of Albrecht V were used to shape Catholic identity in Bavaria during the establishment of confessional boundaries in late sixteenth-century Europe. This study presents a methodological framework for understanding early modern patronage in which the arts are necessarily viewed as interconnected, and patronage is understood as a complex and often contradictory process that involved all elements of society. First, this study examines the legacy of arts patronage that Albrecht V inherited from his Wittelsbach predecessors and developed during his reign, from 1550-1579. Albrecht V‟s patronage is then divided into three areas: northern princely humanism, traditional religion and sociological propaganda. -

Frankfurtrhinemain in Figures 2019

European Institutions European Central Bank (ECB) European Space Operations Centre (ESOC) European Meteorological Satellite Organisation (EUMETSAT) European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) Tourism in FrankfurtRhineMain No. of hotels and guest houses 2,887 FrankfurtRhineMain No. of beds 165,548 Total guests 12,936,055 Guests from abroad in percent 29.2 % Total overnight stays 26,123,146 Average duration of stay 2.0 days in figures 2019 Figures per: 2017 Transport Infrastructure FrankfurtRhineMain Total of classified roads 11,420 km including Federal highways (Bundesautobahnen) 1,448 km Long distance stations 18 Ports along the rivers Rhine and Main 7 Figures per: 01.01.2018 FrankfurtRhineMain In the RhineMain region 7.9 % of the German gross value is generated. The Hessian part of the region realises Frankfurt International Airport (FRA) a staggering 78 % of the gross domestic product of the federal state of Hessian. These numbers emphasise the status of FrankfurtRhineMain as – according to European standards – one of the most important metropolitan FRA segment within Frankfurt International All German areas of Germany. German airports Airport Airports in percent There is also no lack of international flair: four European institutions are based in the region. More than 2,500 companies from China and the United States alone have settled here. This is not least due to the excellent inf- No. of passengers 64,500,386 27.4 % 235,175,472 rastructure of the region. At 12 international schools, students can obtain an internationally accredited degree. Freight (+Airmail) volume in tons 2,228,969 44.7 % 4,983,656 With over 1,300 flight movements a day, Frankfurt International Airport contributes much to the outstanding accessibility of the metropolitan area for both business travellers and tourists. -

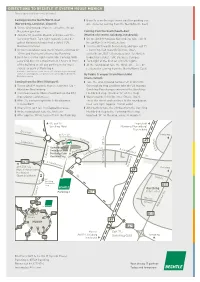

DIRECTIONS to BECHTLE IT SYSTEM HOUSE MUNICH Please Observe All Low-Emission Zones!

DIRECTIONS TO BECHTLE IT SYSTEM HOUSE MUNICH Please observe all low-emission zones! Coming from the North/North-East Bechtle is on the right-hand side (for parking see (Nuremberg, Landshut, airport): directions for coming from the North/North-East) On the A92 towards Munich, exit at the Kreuz Neufahrn junction Coming from the South/South-East Join the A9 towards Munich and take exit 70 – (Munich city centre, Salzburg, Innsbruck): Garching-Nord. Turn right towards Gewerbe- On the A8/A99 towards Nuremberg, take exit 13 – gebiet Hochbrück (industrial estate), TÜV, Kreuz München-Nord junction Business Campus Join the A9 towards Nuremberg and take exit 71 At the roundabout take the third exit, continue for – Garching-Süd towards Dachau, Ober- 100 m and then turn left onto the Parkring schleißheim, B471, Gewerbegebiet Hochbrück Bechtle is on the right-hand side. Parking: With (industrial estate), TÜV, Business Campus a parking disc for a maximum of 2 hours in front Turn right at the first set of traffic lights of the building or all-day parking in the multi- At the roundabout take the third exit ... (see di- storey car park at Parkring 4. rections for coming from the North/North-East) Parking is available at a reduced fee of € 4.50 per day for training/ conference participants. Car park tickets can be obtained from the By Public Transport from Munich Hbf Bechtle reception. (main station): Coming from the West (Stuttgart): Take the underground number U4 or U5 to the On the A8/A99 towards Munich, take exit 12a – Odeonsplatz stop and then take the U6 towards München-Neuherberg Garching-Forschungszentrum to the Garching- Continue towards Oberschleißheim on the B13 – Hochbrück stop (marked “U” on the map) Ingolstädter Landstrasse Walk towards Schleißheimer Strasse/B471, After 3.5 km turn right into Schleißheimer cross the street and continue to the roundabout, Strasse/B471 then turn right (approx. -

Aschaffenburg Zu Fuß

8 Monika Spatz Aschaffenburg zu Fuß Die schönsten Sehenswürdigkeiten zu Fuß entdecken Die Angaben und Informationen in diesem Buch sind aktuell re- cherchiert und vor Drucklegung sorgfältig überprüft worden. Trotz- dem ist darauf hinzuweisen, dass sich Telefonnummern, Öffnungs- zeiten und andere Angaben im Lauf der Zeit ändern können. Bildnachweis für alle Bilder: Dr. Karl Spatz Seite 2: Das Pompejanum 2., ergänzte und überarbeitete Auflage Alle Rechte vorbehalten • Societäts-Verlag © 2020 Frankfurter Societäts-Medien GmbH Satz: Julia Desch, Societäts-Verlag Umschlaggestaltung: Julia Desch, Societäts-Verlag Umschlagabbildung: Dr. Karl Spatz Karten: Peh & Schefcik Druck und Verarbeitung: CPI books GmbH, Leck Printed in Germany 2020 www.societaets-verlag.de www.facebook.com/societaetsverlag ISBN 978-3-95542-356-8 Inhalt Vorwort ...........................................................................................................7 Kapitel 1 Ein Gang durch die Altstadt ..................... 8 Kapitel 2 Das Grüne Band ...........................................32 Kapitel 3 Wenn alle Brünnlein fließen ................. 48 Kapitel 4 Rund ums Schloss ......................................62 Kapitel 5 Kunst, Kino, Musik und Theater — von allem etwas ............................................. 76 Kapitel 6 Auf verschlungenen Wegen ..................90 Kapitel 7 Kippenburg und Teufelskanzel .........106 Kapitel 8 Steine erzählen Geschichte ..................116 Service .......................................................................................................126 -

Part II, Chapter 6

Cover Page The handle http://hdl.handle.net/1887/38762 holds various files of this Leiden University dissertation. Author: Gottschalk, Linda Stuckrath Title: Pleading for diversity : the church Caspar Coolhaes wanted Issue Date: 2016-04-06 Chapter 5: Mature preoccupations Coolhaes occupied himself with several causes throughout the years of his maturity, even while he continued his distilling and then eventually turned the business over to his son. He translated and defended Sebastian Franck, the German Spiritualist. He advocated toleration of Mennonites. In a fictious work, he painted some Catholics in a positive light, while at the same time, in non-fiction, combated what he perceived as residual Catholic superstitious practices in society. He also rebuked Arminius and Gomarus over their conflict at Leiden University. These interests consumed him intensely. We will look in greater depth at each of these “preoccupations” by examining his writings on each cause. Sebastian Franck via Coolhaes The ideas of Sebastian Franck were well-known in the Netherlands. Franck was a major influence on such figures as Coornhert.1 Two books which defend Franck are linked to Coolhaes. For the first, his authorship is not at all certain. The second, however, is surely written by Coolhaes. We will explore this below. Since this dissertation’s main topic is Coolhaes’ ecclesiology, and since the foundation of that ecclesiology is, in our opinion, his Spiritualism, and since, furthermore, he was inspired a great deal by Franck in that Spiritualism, a more pointed discussion of Franck will come later under the heading of ecclesiology in Part II, Chapter 6. -

Lessons in Morality in a Changing World Allegories of Virtue and Vice in the Baillieu Library Print Collection Amelia Saward

Lessons in morality in a changing world Allegories of virtue and vice in the Baillieu Library Print Collection Amelia Saward As evident in texts ranging from the concurrent rediscoveries of ancient Hieronymus Wierix (c. 1553–1619).6 Bible to the writings of Aristotle philosophical teachings. Giotto’s The two representations of vice— and Thomas Aquinas, humans have figures of the virtues and vices Pride and Lust—are part of tried for millennia to understand and (situated below the cycle of frescoes Aldegrever’s series. explain the concept of morality and, on the life of the Virgin and Christ) The Raimondi prints, as well as more precisely, the human virtues and in the Scrovegni Chapel (Arena the majority of those by Beham and vices. Consequently, it is no surprise Chapel) at Padua, dating from Aldegrever, are from the significant that representations of morality 1303–05, are one of the earliest gift made by Dr J. Orde Poynton populate Western art throughout Renaissance examples.2 Along with (1906–2001) in 1959, while the history. Such representations usually an advanced understanding of time remaining prints mentioned were take the form of allegory. In the and temporality that began in the purchased by the university, bar one Renaissance’s age of humanism, medieval period, this re-emergence donated in recent years by Marion where Church principles and pagan of ancient theories heralded an era and David Adams.7 traditions were paradoxically mixed, characterised by an unsurpassed Although morality has been these representations demonstrated desire to understand the human a subject of human inquiry since the emergence and establishment of condition. -

Nuts-Map-DE.Pdf

GERMANY NUTS 2013 Code NUTS 1 NUTS 2 NUTS 3 DE1 BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG DE11 Stuttgart DE111 Stuttgart, Stadtkreis DE112 Böblingen DE113 Esslingen DE114 Göppingen DE115 Ludwigsburg DE116 Rems-Murr-Kreis DE117 Heilbronn, Stadtkreis DE118 Heilbronn, Landkreis DE119 Hohenlohekreis DE11A Schwäbisch Hall DE11B Main-Tauber-Kreis DE11C Heidenheim DE11D Ostalbkreis DE12 Karlsruhe DE121 Baden-Baden, Stadtkreis DE122 Karlsruhe, Stadtkreis DE123 Karlsruhe, Landkreis DE124 Rastatt DE125 Heidelberg, Stadtkreis DE126 Mannheim, Stadtkreis DE127 Neckar-Odenwald-Kreis DE128 Rhein-Neckar-Kreis DE129 Pforzheim, Stadtkreis DE12A Calw DE12B Enzkreis DE12C Freudenstadt DE13 Freiburg DE131 Freiburg im Breisgau, Stadtkreis DE132 Breisgau-Hochschwarzwald DE133 Emmendingen DE134 Ortenaukreis DE135 Rottweil DE136 Schwarzwald-Baar-Kreis DE137 Tuttlingen DE138 Konstanz DE139 Lörrach DE13A Waldshut DE14 Tübingen DE141 Reutlingen DE142 Tübingen, Landkreis DE143 Zollernalbkreis DE144 Ulm, Stadtkreis DE145 Alb-Donau-Kreis DE146 Biberach DE147 Bodenseekreis DE148 Ravensburg DE149 Sigmaringen DE2 BAYERN DE21 Oberbayern DE211 Ingolstadt, Kreisfreie Stadt DE212 München, Kreisfreie Stadt DE213 Rosenheim, Kreisfreie Stadt DE214 Altötting DE215 Berchtesgadener Land DE216 Bad Tölz-Wolfratshausen DE217 Dachau DE218 Ebersberg DE219 Eichstätt DE21A Erding DE21B Freising DE21C Fürstenfeldbruck DE21D Garmisch-Partenkirchen DE21E Landsberg am Lech DE21F Miesbach DE21G Mühldorf a. Inn DE21H München, Landkreis DE21I Neuburg-Schrobenhausen DE21J Pfaffenhofen a. d. Ilm DE21K Rosenheim, Landkreis DE21L Starnberg DE21M Traunstein DE21N Weilheim-Schongau DE22 Niederbayern DE221 Landshut, Kreisfreie Stadt DE222 Passau, Kreisfreie Stadt DE223 Straubing, Kreisfreie Stadt DE224 Deggendorf DE225 Freyung-Grafenau DE226 Kelheim DE227 Landshut, Landkreis DE228 Passau, Landkreis DE229 Regen DE22A Rottal-Inn DE22B Straubing-Bogen DE22C Dingolfing-Landau DE23 Oberpfalz DE231 Amberg, Kreisfreie Stadt DE232 Regensburg, Kreisfreie Stadt DE233 Weiden i.