Studies and Analyses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Modern India Reinvented Classical Dance

ESSAY espite considerable material progress, they have had to dispense with many aspects of the the world still views India as an glorious tradition that had been built up over several ancient land steeped in spirituality, centuries. The arrival of the Western proscenium stage with a culture that stretches back to in India and the setting up of modern auditoria altered a hoary, unfathomable past. Indians, the landscape of the performing arts so radically that too, subscribe to this glorification of all forms had to revamp their presentation protocols to its timelessness and have been encouraged, especially survive. The stone or tiled floor of temples and palaces Din the last few years, to take an obsessive pride in this was, for instance, replaced by the wooden floor of tryst with eternity. Thus, we can hardly be faulted in the proscenium stage, and those that had an element subscribing to very marketable propositions, like the of cushioning gave an ‘extra bounce’, which dancers one that claims our classical dance forms represent learnt to utilise. Dancers also had to reorient their steps an unbroken tradition for several millennia and all of and postures as their audience was no more seated all them go back to the venerable sage, Bharata Muni, who around them, as in temples or palaces of the past, but in composed Natyashastra. No one, however, is sure when front, in much larger numbers than ever before. Similarly, he lived or wrote this treatise on dance and theatre. while microphones and better acoustics management, Estimates range from 500 BC to 500 AD, which is a coupled with new lighting technologies, did help rather long stretch of time, though pragmatists often classical music and dance a lot, they also demanded re- settle for a shorter time band, 200 BC to 200 AD. -

Odissi Dance

ORISSA REFERENCE ANNUAL - 2005 ODISSI DANCE Photo Courtesy : Introduction : KNM Foundation, BBSR Odissi dance got its recognition as a classical dance, after Bharat Natyam, Kathak & Kathakali in the year 1958, although it had a glorious past. The temple like Konark have kept alive this ancient forms of dance in the stone-carved damsels with their unique lusture, posture and gesture. In the temple of Lord Jagannath it is the devadasis, who were performing this dance regularly before Lord Jagannath, the Lord of the Universe. After the introduction of the Gita Govinda, the love theme of Lordess Radha and Lord Krishna, the devadasis performed abhinaya with different Bhavas & Rasas. The Gotipua system of dance was performed by young boys dressed as girls. During the period of Ray Ramananda, the Governor of Raj Mahendri the Gotipua style was kept alive and attained popularity. The different items of the Odissi dance style are Mangalacharan, Batu Nrutya or Sthayi Nrutya, Pallavi, Abhinaya & Mokhya. Starting from Mangalacharan, it ends in Mokhya. The songs are based upon the writings of poets who adored Lordess Radha and Krishna, as their ISTHADEVA & DEVIS, above all KRUSHNA LILA or ŎRASALILAŏ are Banamali, Upendra Bhanja, Kabi Surya Baladev Rath, Gopal Krishna, Jayadev & Vidagdha Kavi Abhimanyu Samant Singhar. ODISSI DANCE RECOGNISED AS ONE OF THE CLASSICAL DANCE FORM Press Comments :±08-04-58 STATESMAN őIt was fit occasion for Mrs. Indrani Rehman to dance on the very day on which the Sangeet Natak Akademy officially recognised Orissi dancing -

Odisha Review Dr

Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 Index of Orissa Review (April-1948 to May -2013) Sl. Title of the Article Name of the Author Page No. No April - 1948 1. The Country Side : Its Needs, Drawbacks and Opportunities (Extracts from Speeches of H.E. Dr. K.N. Katju ) ... 1 2. Gur from Palm-Juice ... 5 3. Facilities and Amenities ... 6 4. Departmental Tit-Bits ... 8 5. In State Areas ... 12 6. Development Notes ... 13 7. Food News ... 17 8. The Draft Constitution of India ... 20 9. The Honourable Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru's Visit to Orissa ... 22 10. New Capital for Orissa ... 33 11. The Hirakud Project ... 34 12. Fuller Report of Speeches ... 37 May - 1948 1. Opportunities of United Development ... 43 2. Implication of the Union (Speeches of Hon'ble Prime Minister) ... 47 3. The Orissa State's Assembly ... 49 4. Policies and Decisions ... 50 5. Implications of a Secular State ... 52 6. Laws Passed or Proposed ... 54 7. Facilities & Amenities ... 61 8. Our Tourists' Corner ... 61 9. States the Area Budget, January to March, 1948 ... 63 10. Doings in Other Provinces ... 67 1 Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 11. All India Affairs ... 68 12. Relief & Rehabilitation ... 69 13. Coming Events of Interests ... 70 14. Medical Notes ... 70 15. Gandhi Memorial Fund ... 72 16. Development Schemes in Orissa ... 73 17. Our Distinguished Visitors ... 75 18. Development Notes ... 77 19. Policies and Decisions ... 80 20. Food Notes ... 81 21. Our Tourists Corner ... 83 22. Notice and Announcement ... 91 23. In State Areas ... 91 24. Doings of Other Provinces ... 92 25. Separation of the Judiciary from the Executive .. -

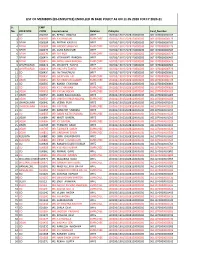

List of Members (Ex-Employee) Enrolled in Base Policy As on 11.05.2020 for Fy 2020-21

LIST OF MEMBERS (EX-EMPLOYEE) ENROLLED IN BASE POLICY AS ON 11.05.2020 FOR FY 2020-21 Sr. EMP No. LOCATION CODE Insured name Relation PolicyNo Card_Number 1 CO 00016G MS. REENA JHINGAN WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000103 2 CO 00016G MR. K K JHINGAN EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000126 3 DELHI 00030B MS. PRITPAL KAUR VIJ WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000203 4 DELHI 00030B MR. ANOOP SINGH VIJ EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000226 5 DELHI 00037K MS. ASHA RANI PURI WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000303 6 DELHI 00037K MR. D D PURI EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000326 7 DELHI 00041H MS. VIDYAWATI RANGRA WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000403 8 DELHI 00041H MR. BIDHU RAM RANGRA EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000426 9 AHMEDABAD 00042A MS. CHANDER TANEJA WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000503 10 AHMEDABAD 00042A MR. VAS DEV TANEJA EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000526 11 CO 00043D MS. LALTHANZAUVI WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000603 12 CO 00043D MR. SAJEEVAN LAL EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000626 13 DELHI 00045L MR. SRI KRISHAN GANDHI EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000726 14 CO 00050G MS. KANAK CHAUHAN WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000803 15 CO 00050G MR. K S CHAUHAN EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000826 16 DELHI 00051E MR. K K SACHDEVA EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000926 17 DELHI 00055H MS. SAROJ BALA NAGPAL WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000001003 18 DELHI 00055H MR. VINOD KUMAR NAGPAL EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000001026 19 CHANDIGARH 00064G MS. VEENA PURI WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000001103 20 CHANDIGARH 00064G MR. V K PURI EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000001126 21 CO 00065E MS. KAMLESH SHARMA WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000001203 22 CO 00065E MR. BADRI NATH SHARMA EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000001226 23 DELHI 00069H MS. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

(Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl

MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (Public Section) Padma Awards Directory (1954-2009) Year-Wise List Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 1954 1 Dr. Sarvapalli Radhakrishnan BR TN Public Affairs Expired 2 Shri Chakravarti Rajagopalachari BR TN Public Affairs Expired 3 Dr. Chandrasekhara Raman BR TN Science & Eng. Expired Venkata 4 Shri Nand Lal Bose PV WB Art Expired 5 Dr. Satyendra Nath Bose PV WB Litt. & Edu. 6 Dr. Zakir Hussain PV AP Public Affairs Expired 7 Shri B.G. Kher PV MAH Public Affairs Expired 8 Shri V.K. Krishna Menon PV KER Public Affairs Expired 9 Shri Jigme Dorji Wangchuk PV BHU Public Affairs 10 Dr. Homi Jehangir Bhabha PB MAH Science & Eng. Expired 11 Dr. Shanti Swarup Bhatnagar PB UP Science & Eng. Expired 12 Shri Mahadeva Iyer Ganapati PB OR Civil Service 13 Dr. J.C. Ghosh PB WB Science & Eng. Expired 14 Shri Maithilisharan Gupta PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 15 Shri Radha Krishan Gupta PB DEL Civil Service Expired 16 Shri R.R. Handa PB PUN Civil Service Expired 17 Shri Amar Nath Jha PB UP Litt. & Edu. Expired 18 Shri Malihabadi Josh PB DEL Litt. & Edu. 19 Dr. Ajudhia Nath Khosla PB DEL Science & Eng. Expired 20 Shri K.S. Krishnan PB TN Science & Eng. Expired 21 Shri Moulana Hussain Madni PB PUN Litt. & Edu. Ahmed 22 Shri V.L. Mehta PB GUJ Public Affairs Expired 23 Shri Vallathol Narayana Menon PB KER Litt. & Edu. Expired Wednesday, July 22, 2009 Page 1 of 133 Sl. Prefix First Name Last Name Award State Field Remarks 24 Dr. -

Utilization of 'Urni' in Our Daily Life

International Journal of Research p-ISSN: 2348-6848 e-ISSN: 2348-795X Available at https://edupediapublications.org/journals Volume 03 Issue 12 August 2016 Utilization of ‘Urni’ in Our Daily Life Mr. Ashis Kumar Pradhan1, Dr. Subimalendu Bikas Sinha 2 1Research Scholar, Bhagwant University, Ajmer, Rajasthan, India 2 Emeritus Fellow, U.G.C and Ex Principal, Indian college arts & Draftsmanship, kolkata “Urni‟ is manufactured by few weaving Abstract techniques with different types of clothing. It gained ground as most essential and popular „Urni‟ is made by cotton, silk, lilen, motka, dress material. Starting in the middle of the tasar & jute. It is used by men and women. second millennium BC, Indo-European or „Urni‟ is an unstitched and uncut piece of cloth Aryan tribes migrated keen on North- Western used as dress material. Yet it is not uniformly India in a progression of waves resulting in a similar in everywhere it is used. It differs in fusion of cultures. This is the very juncture variety, form, appearance, utility, etc. It bears when latest dynasties were formed follow-on the identity of a country, region and time. the flourishing of clothing style of which the „Urni‟ was made in different types and forms „Urni‟ type was a rarely main piece. „Urni‟ is a for the use of different person according to quantity of fabric used as dress material in position, rank, purpose, time and space. Along ancient India to cover the upper part of the with its purpose as dress material it bears body. It is used to hang from the neck to drape various religious values, royal status, Social over the arms, and can be used to drape the position, etc. -

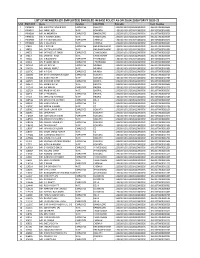

LIST of MEMBERS (EX-EMPLOYEES) ENROLLED in BASE POLICY AS on 20.04.2020 for FY 2020-21 S.NO EMPCODE Name Relation LOCATION Policyno Card Number 1 PRMB22 MR

LIST OF MEMBERS (EX-EMPLOYEES) ENROLLED IN BASE POLICY AS ON 20.04.2020 FOR FY 2020-21 S.NO EMPCODE Name Relation LOCATION PolicyNo Card_Number 1 PRMB22 MR. SWAPAN KUMAR ROY EMPLOYEE KOLKATA :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283626 2 PRMB22 MS. DIPALI ROY WIFE KOLKATA :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283603 3 PRMB19 MR. M AKBARSHA EMPLOYEE BANGALORE :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283526 4 PRMB19 MS. A HAMIDA BANU WIFE BANGALORE :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283503 5 PRMB09 MR. T S VIJAYAKUMAR EMPLOYEE CHENNAI :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283426 6 PRMB09 MS. V KALAIVANI WIFE CHENNAI :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283403 7 14819J MR. P N PATRI EMPLOYEE BHUBANESHWAR :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283326 8 14819J MS. GEETANJALI PATRI WIFE BHUBANESHWAR :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283303 9 14027J MR. JATINDERJIT SINGH EMPLOYEE CHANDIGARH :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283226 10 14027J MS. JASWANT KAUR WIFE CHANDIGARH :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283203 11 13346J MS. D RAMADEVI EMPLOYEE HYDERABAD :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283126 12 13314L MS. P SABIRUNNISA EMPLOYEE HYDERABAD :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283026 13 12435D MR. H C RAJPUT EMPLOYEE MUMBAI :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000282926 14 12435D MS. MANJU RAJPUT WIFE MUMBAI :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000282903 15 12363C MR. N R DAS EMPLOYEE MUMBAI :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000282826 16 12358G MR. BHIM CHANDRA HALDER EMPLOYEE KOLKATA :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000282726 -

Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICD Section) Indian Cultural Programmes 2012 April-March 2013 S.No. Name of the Programme

Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICD Section) Indian Cultural Programmes 2012 April-March 2013 S.No. Name of the Programmes Style Date of Performance 1. Ms. Sonam Kalra Sufi Singer 12th April, 2012 2. Ms. Swaswati Sen Kathak 12th April, 2012 3. Dr. Ileana Citaristi Odissi (H) 13th April, 2012 4. Ms. Nibedita Mohapatra Odissi (Lec-dem) 17th April, 2012 5. Mr. Manish Sharma Jal Tarang (H) 20th April, 2012 6. Mr. Ustad Mazhar Ali Vocal 21st April, 2012 Khan,Ustad Jawaad Ali Khan & Hans Raj Hans 7. Matrix Creative group Bollywood Dhamaka 23rd April, 2012 8. Mr. Rajat Kapoor Theater 26th April, 2012 9. Ms. Aruna Vasude Buddist (H) 27th April, 2012 10. Ms. Pragati Sood Kathak Lec-dem 2nd May, 2012 11. Mr. Sudip Kr. Flute recital (H) 4th May, 2012 Chattopadayay, Kolkata 12. Ms. Sangeeta Sharma Theatre (H) 11th May, 2012 13. Ms. Kavita Divedi Lec dem 13th May, 2012 14. Ms. Sohaila Kapur Dance Theatre (H) 18th May, 2012 15. Ms. Anjana Jha Kathak (H) 25th May, 2012 16. Ms. Ashvari Majumdar Kathak (Lec. Dem) 30th May, 2012 17. Prof. Lovely Sharma Sitar Recital (H) Agra 1st June, 2012 18. Mr. Anil Bhatt Puppet Show (H) 8th June, 2012 19. Mrs. Rina Jana Odissi Dance (H) 15th June, 2012 Kolkata 20. Mr. Neel Ranjan Mukherjee Hawaiian Guitar (H) 22nd June, 2012 21. Dr. Janaki Rangarajan Bharatanatyam (H) 29th June, 2012 Chennai 22. Mr. Shekhar Sen from “Kabeer” Play 2nd July, 2012 Mumbai 23. Malhaar Festival-2012 1. Meeta Pandit Hindustani Vocal 8th July, 2012 2. Rama Vaidyanathan Bharatanatyam 8th July, 2012 3. -

Odisha Review

ODISHA REVIEW VOL. LXXIV NO.4 NOVEMBER - 2017 SURENDRA KUMAR, I.A.S. Commissioner-cum-Secretary LAXMIDHAR MOHANTY, O.A.S Director DR. LENIN MOHANTY Editor Editorial Assistance Production Assistance Bibhu Chandra Mishra Debasis Pattnaik Bikram Maharana Sadhana Mishra Cover Design & Illustration D.T.P. & Design Manas Ranjan Nayak Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Photo Kishor Kumar Sinha Raju Singh Manoranjan Mohanty Niranjan Baral The Odisha Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Odisha’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Odisha Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Odisha. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Odisha Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. Rs.5/- Five Rupees / Copy E-mail : [email protected] Visit : http://odisha.gov.in Contact : 9937057528(M) CONTENTS Good Governance ... ... 1 Baliyatra : A Festival of Odisha's Ancient Maritime Trade Dr. Rabindra Nath Dash ... 13 Measuring Fiscal Performance of Indian States with Special Dr. Bibhuti Ranjan Mishra ... 17 Reference to Odisha Prof. Asit Ranjan Mohanty Kalinga and Champa : A Study in Ancient Maritime Relations Dr. Benudhar Patra ... 22 Paika Rebellion of 1817 : The First Independence War of India Akshyaya Kumar Nayak ... 27 Boita Bandana Festival and Water Pollution Dr. Manas Ranjan Senapati ... 32 Odisha Welcomes the World as Tourist But Bids Farewell as Friend Debadutta Rath ... 34 Exploring the Lost River(s) at Konark : Chirashree Srabani Rath, ... 39 A Multi-Disciplinary Approach Rashmi Ranjan Behera, Subhomay Jana, Priyadarshi Patnaik, and William K. -

Odissi Dance) 2020 THREE YEAR FULL TIME PROGRAMME

Learning Outcome based Curriculum Framework (LOCF) For Undergraduate Programme B.P.A. (Odissi Dance) 2020 THREE YEAR FULL TIME PROGRAMME Syllabus and Scheme of Examination This shall be applicable for students seeking admission in B.P.A. Odissi Dance Programme in 2020-2021 DEPARTMENT OF PERFORMING ARTS Faculty of Indic Studies Sri Sri University DPA-B.P.A. (O.D.) Page 0 Introduction – The proposed programme shall be conducted and supervised by the Faculty of Indic Studies, Department of Performing Arts, Sri Sri University, Cuttack (Odisha). This programme has been designed on the Learning Outcomes Curriculum Framework (LOCF) under UGC guidelines, offers flexibility within the structure of the programme while ensuring the strong foundation and in-depth knowledge of the discipline. The learning outcome-based curriculum ensures its suitability in the present day needs of the student towards higher education and employment. The Department of Performing Arts at Sri Sri University is now offering bachelor degree program with specialization in Performing Arts (Odissi Dance and Hindustani Vocal Music) Vision – The Department of Performing Arts aims to impart holistic education to equip future artistes to achieve the highest levels of professional ability, in a learning atmosphere that fosters universal human values through the Performing Arts. To preserve, perpetuate and monumentalize through the Guru-Sishya Parampara (teacher-disciple tradition) the classical performing arts in their essence of beauty, harmony and spiritual evolution, giving scope for innovation and continuity with change to suit modern ethos. Mission : To be a center of excellence in performing arts by harnessing puritan skills from Vedic days to modern times and creating artistic expressions through learned human ingenuity of emerging times for furtherance of societal interest in the visual & performing arts. -

ART VISION POSTER 3 Page

Art Vision @25 India Habitat Centre in collaboration with Art Vision presents DANCE ACROSS GENRES 5 Series Online Conversations From 21- 25th July daily 9 - 10 pm Target Audience: On Zoom and Live on Facebook Art Vision Page Dance students India Habitat Centre Members, Moderated by Ileana Citaristi Visual Artists, Moviemakers, Museum Enthusiast, Theatre Artists, 21, July 2021 Museums Cultural Practitioners, Reviewing Dance: Alastair Maculay Curators and, beyond 22, July 2021 Dance and Theatre: Julia Varley 23 July, 2021 Dance and Visual Arts: Alka Pande 24 July, 2021 Dance and Films: Deirdre Towers 25 July, 2021 Dance and Bhakti: Parvathy Baul Alistair Macaulay Julia Varley Alka Pande Deirdre Towers Parvathy Baul For Registration please scan QR CODE or for more information visit the link below: https://indiahabitat.org/page?view=registrations Art Vision @25 India Habitat Centre in collaboration with Art Vision presents DANCE ACROSS GENRES Art Vision was founded in 1996 by Smt. Ileana Citaristi along with a group of artists belonging to different disciplines such as dance, painting , cinema and literature who wanted to have a common ground for sharing experiences and creative ideas. During these years Art Vision has conducted several events, which reflect its multi disciplinary nature. As part of the 25 years celebration of Art Vision, the series Dance across Genres have been organized in collaboration with India Habitat Centre. Ileana Citaristi is an Italian-born Odissi and Chhau dancer, and dance instructor based in Bhubaneswar, India. She was awarded the 43rd National Film Awards for Best Choreography for Yugant in 1995 and became, in 2006, the first dancer of foreign origin to be conferred the Padma Shri for her contributions to Odissi.