Death Penalty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuba and the World.Book

CUBA FUTURES: CUBA AND THE WORLD Edited by M. Font Bildner Center for Western Hemisphere Studies Presented at the international symposium “Cuba Futures: Past and Present,” organized by the The Cuba Project Bildner Center for Western Hemisphere Studies The Graduate Center/CUNY, March 31–April 2, 2011 CUBA FUTURES: CUBA AND THE WORLD Bildner Center for Western Hemisphere Studies www.cubasymposium.org www.bildner.org Table of Contents Preface v Cuba: Definiendo estrategias de política exterior en un mundo cambiante (2001- 2011) Carlos Alzugaray Treto 1 Opening the Door to Cuba by Reinventing Guantánamo: Creating a Cuba-US Bio- fuel Production Capability in Guantánamo J.R. Paron and Maria Aristigueta 47 Habana-Miami: puentes sobre aguas turbulentas Alfredo Prieto 93 From Dreaming in Havana to Gambling in Las Vegas: The Evolution of Cuban Diasporic Culture Eliana Rivero 123 Remembering the Cuban Revolution: North Americans in Cuba in the 1960s David Strug 161 Cuba's Export of Revolution: Guerilla Uprisings and Their Detractors Jonathan C. Brown 177 Preface The dynamics of contemporary Cuba—the politics, culture, economy, and the people—were the focus of the three-day international symposium, Cuba Futures: Past and Present (organized by the Bildner Center at The Graduate Center, CUNY). As one of the largest and most dynamic conferences on Cuba to date, the Cuba Futures symposium drew the attention of specialists from all parts of the world. Nearly 600 individuals attended the 57 panels and plenary sessions over the course of three days. Over 240 panelists from the US, Cuba, Britain, Spain, Germany, France, Canada, and other countries combined perspectives from various fields including social sciences, economics, arts and humanities. -

AS/Jur (2019) 50 11 December 2019 Ajdoc50 2019

Declassified AS/Jur (2019) 50 11 December 2019 ajdoc50 2019 Committee on Legal Affairs and Human Rights Abolition of the death penalty in Council of Europe member and observer states,1 Belarus and countries whose parliaments have co-operation status2 – situation report Revised information note General rapporteur: Mr Titus CORLĂŢEAN, Romania, Socialists, Democrats and Greens Group 1. Introduction 1. Having been appointed general rapporteur on the abolition of the death penalty at the Committee meeting of 13 December 2018, I have had the honour to continue the outstanding work done by Mr Yves Cruchten (Luxemburg, SOC), Ms Meritxell Mateu Pi (Andorra, ALDE), Ms Marietta Karamanli (France, SOC), Ms Marina Schuster (Germany, ALDE), and, before her, Ms Renate Wohlwend (Liechtenstein, EPP/CD).3 2. This document updates the previous information note with regard to the development of the situation since October 2018, which was considered at the Committee meeting in Strasbourg on 10 October 2018. 3. This note will first of all provide a brief overview of the international and European legal framework, and then highlight the current situation in states that have abolished the death penalty only for ordinary crimes, those that provide for the death penalty in their legislation but do not implement it and those that actually do apply it. It refers solely to Council of Europe member states (the Russian Federation), observer states (United States, Japan and Israel), states whose parliaments hold “partner for democracy” status, Kazakhstan4 and Belarus, a country which would like to have closer links with the Council of Europe. Since March 2012, the Parliamentary Assembly’s general rapporteurs have issued public statements relating to executions and death sentences in these states or have proposed that the Committee adopt statements condemning capital punishment as inhuman and degrading. -

VADP 2015 Annual Report Accomplishments in 2015

2015 Annual Report Working to End the Death Penalty through Education, Organizing and Advocacy for 24 years VADP Executive Directors, Past and Present From left: Beth Panilaitis (2008 -2010), Steve Northup (2011 -2014), Jack Payden -Travers (2002 -2007), and Michael Stone (2015). Virginians for Alternatives to the Death Penalty P.O. Box 12222 Richmond, VA 23241 (434) 960 -7779 [email protected] www.vadp.org Message from the VADP Board President Dear VADP Supporter, resources to band together the various groups and Last year was a time of strong forward movement individuals who oppose the death penalty, for VADP. In January, we hired Michael Stone, whatever their reasons, into a cohesive force. our first full time executive director in four years, I would like to thank those of you who made a and that led to the implementation of bold new monetary donation to VADP in 2015. But our strategies and expanded programs. work is not done. So I ask you to increase your In 2015 we learned what can be accomplished in support in 2016 and to help us find others to join today’s politics when groups with different overall this important movement. And, if you are not yet purposes decide to work together on a specific a supporter of VADP, now is the time to join our shared objective — such as vital work to end the death penalty in Virginia, death penalty abolition. That, once and for all. happily, is starting to occur. Sincerely, As an example, nationally and Kent Willis in Virginia activists from every Board President point on the political spectrum are joining an extraordinary new movement to re -examine The Death Penalty in Virginia how we waste tax dollars on our expensive and ineffective criminal justice system, including ♦ Virginia has executed 111 men and women capital punishment. -

Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission

The Report of the The Report Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission Review Penalty Oklahoma Death The Report of the Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission OKDeathPenaltyReview.org The Report of the Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission The Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission is an initiative of The Constitution Project®, which sponsors independent, bipartisan committees to address a variety of important constitutional issues and to produce consensus reports and recommendations. The views and conclusions expressed in these reports, statements, and other material do not necessarily reflect the views of members of its Board of Directors or its staff. For information about this report, or any other work of The Constitution Project, please visit our website at www. constitutionproject.org or e-mail us at [email protected]. Copyright © March 2017 by The Constitution Project ®. All rights reserved. No part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of The Constitution Project. Book design by Keane Design & Communications, Inc/keanedesign.com. Table of Contents Letter from the Co-Chairs .........................................................................................................................................i The Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission ..............................................................................iii Executive Summary................................................................................................................................................. -

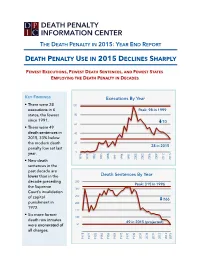

Year End Report

THE DEATH PENALTY IN 2015: YEAR END REPORT DEATH PENALTY USE IN 2015 DECLINES SHARPLY FEWEST EXECUTIONS, FEWEST DEATH SENTENCES, AND FEWEST STATES EMPLOYING THE DEATH PENALTY IN DECADES KEY FINDINGS Executions By Year • There were 28 100 executions in 6 Peak: 98 in 1999 states, the fewest 80 since 1991. ⬇70 60 • There were 49 death sentences in 40 2015, 33% below the modern death 20 28 in 2015 penalty low set last year. 0 • New death 1976 1979 1982 1985 1988 1991 1994 1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 2015 sentences in the past decade are lower than in the Death Sentences By Year decade preceding 350 Peak: 315 in 1996 the Supreme 300 Court’s invalidation of capital 250 ⬇266 punishment in 200 1972. 150 • Six more former 100 death row inmates 49 in 2015 (projected) were exonerated of 50 all charges. 1974 1977 1980 1983 1986 1989 1992 1995 1998 2001 2004 2007 2010 2013 2015 THE DEATH PENALTY IN 2015: YEAR END REPORT U.S. DEATH PENALTY DECLINE ACCELERATES IN 2015 By all measures, use of and support for the death penalty Executions by continued its steady decline in the United States in 2015. The 2015 2014 State number of new death sentences imposed in the U.S. fell sharply from already historic lows, executions dropped to Texas 13 10 their lowest levels in 24 years, and public opinion polls revealed that a majority of Americans preferred life without Missouri 6 10 parole to the death penalty. Opposition to capital punishment polled higher than any time since 1972. -

VADOC Annual Report

Management Information Summary Annual Report For the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 2018 Compiled by the Budget Office On the Cover Re-Entry Opportunities through Food Service Under the Food Services umbrella, offenders have many options for trainings to develop skills that will increase their employability, including participation in the Foundation for Culinary Arts and Restaurant Management Program (Levels I and II), ServSafe Certification, and Cooks and Bakers Apprenticeship Program. Almost Home Café and New Beginnings Restaurant Almost Home Café and New Beginnings Restaurant are located at VADOC’s Headquarters in Richmond. The fully operational cafeteria and restaurant are staffed by female offenders who serve the building’s staff and visitors. The offender workers are securely transported from Central Virginia Correctional Unit and Chesterfield’s Women’s Detention and Diversion Center to Headquarters where they pro- vide breakfast and lunch services for purchase. The offenders in this Culinary Arts program participate in the ServSafe Safe Food Protection Manager Certification Program, as well as Foundations for Culinary Arts and Restaurant Management (Levels I and II) through the National Restaurant Association. The program has is also expanded to include a full scale bakery (Fresh Start Bakery) and offers a Baker’s Apprenticeship through the Agency’s Department of Education. ServSafe Food Protection Manager Certification The ServSafe Program Certification is awarded by the National Restaurant Association. Since May 2011, the VADOC has certified more than 12,500 offenders throughout Virginia’s facilities. Foundations for Culinary Arts and Restaurant Management Foundations for Culinary Arts and Restaurant Management is taught at fourteen facilities. The Staff Dining Halls have been converted into Restaurants where offenders are taught Culinary Arts and Restaurant Management (Levels I and II). -

Prison Calendars 042506 Sorted

PRISON NAME LOCATION CALENDAR Distance Augusta Correctional Center Staunton Staunton 17 Baskerville Correctional Unit Baskerville Lawrenceville 25 Beaumont Correctional Center Beaumont Richmond 26 Bland Correctional Center Bland Blacksburg 33 Botetourt Correctional Unit 2 Troutville Lynchburg 43 Brunswick Correctional Center Lawrenceville Lawrenceville 0 Buckingham Correctional Center Dilwyn Charlottesville 37 Caroline Correctional Center Hanover Richmond 20 Central Virginia Regional Jail Orange Charlottesville 25 Coffeewood Correctional Center Mitchells Charlottesville 33 Cold Springs Correctional Unit Greenville Staunton 9 Commonwealth of Virginia Richmond Richmond 2 Deep Meadow Correctional Center Capron Richmond 55 Deerfield Correctional Center Capron Richmond 55 Dilwyn Correctional Center Dilwyn Charlottesville 37 Dinwiddie Correctional Unit Church Road Richmond 23 Dinwiddie County Jail Dinwiddie Richmond 30 Fairfax Correctional Unit #3 Fairfax Fairfax 0 Fluvanna Correctional Center Troy Charlottesville 14 Greensville Correctional Center Jarratt Richmond 47 Halifax Correctional Unit Halifax Lynchburg 44 Hampton Roads Regional Jail Portsmouth Norfolk 7 Haynesville Correctional Center Haynesville Richmond 53 Henrico County Jail-East Barhamsville Richmond 36 Henrico County Regional Jail Richmond Richmond 5 Indian Creek Correctional Center Chesapeake Norfolk 10 James River Correctional Center State Farm Richmond 21 Keen Mountain Correctional Center Oakwood Wise 40 Lawrenceville Correctional Lawrenceville Lawrenceville 0 Loudon County -

Episode 13: Women Hello and Welcome to the Death Penalty

Episode 13: Women Hello and welcome to the Death Penalty Information Center’s series of podcasts, exploring issues related to capital punishment. In this edition, we will be discussing women and the death penalty. Have women always been represented on death row in the United States? When was the first woman executed? Yes, in theory women have always been eligible for the death penalty in the United States, though they have been executed far less often than men. The first woman executed in what is now the U.S. was Jane Champion, in 1632. She received the death penalty in Virginia for murder. The first woman executed in the modern era of the death penalty was Velma Barfield. She was given a lethal injection in North Carolina in 1984. Do death penalty laws treat men and women differently? No. The laws are written in a gender-neutral way. However, the federal government forbids the execution of a woman who is pregnant. The U.S. has also ratified a treaty with a similar provision. In some countries, criminal laws are specifically written to affect women and men differently. What percentage of death row inmates are women? What percentage of executions involve women? As of October 31, 2010, there were 55 women on death row. They made up 1.7% of all death row inmates. In all of American history, there have only been 569 documented executions of women, out of over 15,000 total executions. Since 1976, twelve women have been executed, accounting for about 1% of executions during that time. -

P7 TA-PROV(2010)0351 World Day Against the Death Penalty

P7_TA-PROV(2010)0351 World Day against the Death Penalty European Parliament resolution of 7 October 2010 on the World day against the death penalty The European Parliament, – having regard to Protocol No 6 to the Convention for the protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms concerning the abolition of the death penalty, of 28 April 1983, – having regard to the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, aiming at the abolition of the death penalty, of 15 December 1989, – having regard to its previous resolutions on the abolition of the death penalty, in particular that of 26 April 2007 on the initiative for a universal moratorium on the death penalty1, – having regard to its resolutions of 26 November 2009 on China: minority rights and application of the death penalty2, of 20 November 2008 on the death penalty in Nigeria3, of 17 June 2010 on executions in Libya4, of 8 July 2010 on North Korea5, of 22 October 2009 on Iran6, of 10 February 2010 on Iran7, and of 8 September 2010 on human rights in Iran, in particular the cases of Mohammadi Ashtiani and Zahra Bahrami8, – having regard to United Nations General Assembly Resolution 62/149 of 18 December 2007 calling for a moratorium on the use of the death penalty, and United Nations General Assembly Resolution 63/168 of 18 December 2008 calling for the implementation of the 2007 General Assembly resolution 62/149, – having regard to the UN Secretary-General’s report to the General Assembly on moratoriums on the use of the death penalty, of -

Visual Culture and Us-Cuban Relations, 1945-2000

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 9-10-2010 INTIMATE ENEMIES: VISUAL CULTURE AND U.S.-CUBAN RELATIONS, 1945-2000 Blair Woodard Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Recommended Citation Woodard, Blair. "INTIMATE ENEMIES: VISUAL CULTURE AND U.S.-CUBAN RELATIONS, 1945-2000." (2010). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/87 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INTIMATE ENEMIES: VISUAL CULTURE AND U.S.-CUBAN RELATIONS, 1945-2000 BY BLAIR DEWITT WOODARD B.A., History, University of California, Santa Barbara, 1992 M.A., Latin American Studies, University of New Mexico, 2001 M.C.R.P., Planning, University of New Mexico, 2001 DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy History The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico May, 2010 © 2010, Blair D. Woodard iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writing of my dissertation has given me the opportunity to meet and work with a multitude of people to whom I owe a debt of gratitude while completing this journey. First and foremost, I wish to thank the members of my committee Linda Hall, Ferenc Szasz, Jason Scott Smith, and Alyosha Goldstein. All of my committee members have provided me with countless insights, continuous support, and encouragement throughout the writing of this dissertation and my time at the University of New Mexico. -

Death Penalty System Is Unconstitutional

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 9 CENTRAL DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 ERNEST DEWAYNE JONES, ) 11 ) Case No.: CV 09-02158-CJC Petitioner, ) 12 ) vs. ) 13 ) ) ORDER DECLARING 14 KEVIN CHAPPELL, Warden of ) CALIFORNIA’S DEATH PENALTY California State Prison at San Quentin, ) SYSTEM UNCONSTITUTIONAL 15 ) AND VACATING PETITIONER’S Respondent. ) DEATH SENTENCE 16 ) ) 17 ) 18 19 20 On April 7, 1995, Petitioner Ernest Dewayne Jones was condemned to death by the 21 State of California. Nearly two decades later, Mr. Jones remains on California’s Death 22 Row, awaiting his execution, but with complete uncertainty as to when, or even whether, 23 it will ever come. Mr. Jones is not alone. Since 1978, when the current death penalty 24 system was adopted by California voters, over 900 people have been sentenced to death 25 for their crimes. Of them, only 13 have been executed. For the rest, the dysfunctional 26 administration of California’s death penalty system has resulted, and will continue to 27 result, in an inordinate and unpredictable period of delay preceding their actual execution. 28 Indeed, for most, systemic delay has made their execution so unlikely that the death -1- 1 sentence carefully and deliberately imposed by the jury has been quietly transformed into 2 one no rational jury or legislature could ever impose: life in prison, with the remote 3 possibility of death. As for the random few for whom execution does become a reality, 4 they will have languished for so long on Death Row that their execution will serve no 5 retributive or deterrent purpose and will be arbitrary. -

Comune Di Villadose Provincia Di Rovigo

DELIBERAZIONE DEL CONSIGLIO COMUNALE COMUNE DI VILLADOSE PROVINCIA DI ROVIGO C O P I A ORDINE DEL GIORNO A DIFESA DI SAKINEH MOHAMMADI ASHTIANI.- Nr. Progr. 61 Data 27/10/2010 Seduta Nr. 13 Adunanza ORDINARIA Seduta PUBBLICA di PRIMA convocazione L'anno DUEMILADIECI questo giorno VENTISETTE del mese di OTTOBRE alle ore 21:00 convocata con le prescritte modalità, Solita sala delle Adunanze si è riunito il Consiglio Comunale. Fatto l'appello nominale risultano: Cognome e Nome Ass. Pres. Cognome e Nome Ass. Pres. ALESSIO GINO X SCHIBUOLA LISA X BELLINI MASSIMO X RIZZATO GIANPIETRO X ROMAGNOLO MARTINA X SANTELLA GIORGIA X CALLEGARO ROBERTO X BRAZZO GIANNI X BARBIERI MATTEO X LIONELLO MICHELE X SOLDÀ RENZO X SIVIERO MARTINA X RENESTO LUCA X FERLIN FABRIANO X PAPARELLA ILARIA X STOCCO FRANCESCO X GIORDANI STEFANO X TOTALE Presenti n. 15 TOTALE Assenti n. 2 Assessori Extraconsiliari ____________________ Presente Assenti Giustificati i signori: BRAZZO GIANNI, SIVIERO MARTINA Assenti Non Giustificati i signori: Nessun convocato risulta assente ingiustificato Assiste alla seduta incaricato della redazione del verbale il SEGRETARIO COMUNALE del Comune, Sig./Sig.ra Dott. ERNESTO BONIOLO. Vengono designati al ruolo di scrutatori i Signori: BELLINI MASSIMO, GIORDANI STEFANO, STOCCO FRANCESCO In qualità di SINDACO, il Sig./Sig.ra GINO ALESSIO assume la presidenza e, constatata la legalità della adunanza, dichiara aperta la seduta invitando il Consiglio Comunale a deliberare sugli oggetti iscritti all'ordine del giorno. DELIBERAZIONE DEL CONSIGLIO COMUNALE NR. 61 DEL 27/10/2010 OGGETTO: ORDINE DEL GIORNO A DIFESA DI SAKINEH MOHAMMADI ASHTIANI.- Il Sindaco illustra i contenuti dell’”Ordine del giorno a difesa di Sakineh Mohammadi Ashtiani” proposto dalla Giunta Comunale; In merito il Sindaco legge anche la dichiarazione del Consigliere Martina SIVIERO , datata 25.10.2010 e pervenuta in pari data al prot.