Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

30Th Annual CMSA Convention

February 2016 • Volume XXXIII #1 30th Annual CMSA Convention by Mark Linkins The 2015 CMSA convention was, by all accounts, a We are also very happy to announce that Neil Gladd tremendous success both musically and organizationally. will be serving as the 2016 Composer-in-Residence! For The Austin team, in conjunction with the CMSA convention many of our readers, Neil Gladd needs no introduction. committee, set a very high standard of expectations for He is one of the foremost figures in the history of the future conventions. Our Philadelphia crew is working mandolin. Gladd appeared as a soloist at Kennedy Center diligently to ensure that the 2016 Convention – which and Carnegie Hall. He also performed with the National happens to be the 30th CMSA Symphony, under Leonard convention – will be a special and Slatkin, and with the Philadelphia memorable event for all attendees! Orchestra, under Rostropovich. A critically acclaimed recording CONFERENCE PROGRAM artist, Gladd produced numerous The 2016 Convention will be classical and ragtime albums over organized around the theme the course of three decades. of ensemble and orchestra performance. Given the fact Gladd is also a prolific composer. that a high percentage of CMSA He has written works for a attendees are members of wide range of instrumental and mandolin orchestras or ensembles, vocal configurations. Many of we thought there would be value in these include mandolin, as solo shining a light on issues pertinent instrument or in combination with to performing with others. This other instruments. As a composer, theme will be reflected in the Gladd’s work references diverse selection of guest artists and musical genres: from the English workshop topics. -

UNIVERSITY of $ASKATCHEWAN This Volume Is The

UNIVERSITY OF $ASKATCHEWAN This volume is the property of the University of Saskatchewan, and the Itt.rory rights of the author and of the University must be respected. If the reader ob tains any assistance from this volume, he must give proper credit in his ownworkr This Thesis by . EJi n.o r • C '.B • C j-IEJ- S0 M has been used by the following persons, whose slgnature~ attest their acc;eptance of the above restri ctions . Name and Address Date , UNIVERSITY OF SASKATCHEWAN The Faculty of Graduate Studies, University of Saskatchewan. We, the undersigned members of the Committee appointed by you to examine the Thesis submitted by Elinor C. B. Chelsom, B.A., B;Ed., in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts, beg to report that we consider the thesis satisfactory both in form and content. Subject of Thesis: ttWilla Cather And The Search For Identity" We also report that she has successfully passed an oral examination on the general field of the subject of the thesis. 14 April, 1966 WILLA CATHER AND THE SEARCH FOR IDENTITY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Mas ter of Arts in the Department of English University of Saskatchewan by Elinor C. B. Chelsom Saskatoon, Saskatchewan April, 1966 Copyrigh t , 1966 Elinor C. B. Chelsom IY 1 s 1986 1 gratefully acknowledge the wise and encouraging counsel of Carlyle King, B.A., M.A., Ph.D. my supervisor in the preparation of this thesis. -

Native American Literature

ENGL 5220 Nicolas Witschi CRN 15378 Sprau 722 / 387-2604 Thursday 4:00 – 6:20 office hours: Wednesday 12:00 – 2:00 Brown 3002 . and by appointment e-mail: [email protected] Native American Literature Over the course of the last four decades or so, literature by indigenous writers has undergone a series of dramatic and always interesting changes. From assertions of sovereign identity and engagements with entrenched cultural stereotypes to interventions in academic and critical methodologies, the word-based art of novelists, dramatists, critics, and poets such as Sherman Alexie, Louise Erdrich, Louis Owens, N. Scott Momaday, Leslie Marmon Silko, Simon Ortiz, and Thomas King, among many others, has proven vital to our understanding of North American culture as a whole. In this course we will examine a cross-section of recent and exemplary texts from this wide-reaching literary movement, paying particular attention to the formal, thematic, and critical innovations being offered in response to questions of both personal and collective identity. This course will be conducted seminar-style, which means that everyone is expected to contribute significantly to discussion and analysis. TEXTS: The following texts are available at the WMU Bookstore: The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, by Sherman Alexie (Spokane) The Last Report on the Miracles at Little No Horse, by Louise Erdrich (Anishinaabe) Bloodlines: Odyssey of a Native Daughter, by Janet Campbell Hale (Coeur d'Alene) The Light People, by Gordon D. Henry (Anishinaabe) Green Grass, Running Water, by Thomas King (Cherokee) House Made of Dawn, by N. Scott Momaday (Kiowa) from Sand Creek, by Simon Ortiz (Acoma) Nothing But The Truth, eds. -

EVIDENCE and INTERPRETATION in TWENTIETH-CENTURY INVESTIGATION NARRATIVES Erin Bartels Buller a Disse

THE UNLOCKED ROOM PROBLEM: EVIDENCE AND INTERPRETATION IN TWENTIETH-CENTURY INVESTIGATION NARRATIVES Erin Bartels Buller A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2013 Approved by: Minrose Gwin Linda Wagner-Martin Ruth Salvaggio John Marx Christopher Teuton ©2013 Erin Bartels Buller ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT ERIN BARTELS BULLER: The Unlocked Room Problem: Evidence and Interpretation in Twentieth-Century Investigation Narratives (Under the direction of Minrose Gwin) This project examines how a range of 20 th -century fictions and memoirs use tropes borrowed from detective fiction to understand the past. It considers the way the historiographical endeavor and the idea of evidence and interpretation are presented in William Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom! , Go Down Moses, Intruder in the Dust , and the stories in Knight’s Gambit ; Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men ; Louis Owens’s The Sharpest Sight and Bone Game ; and Lillian Hellman’s memoirs ( An Unfinished Woman, Pentimento, Scoundrel Time , and Maybe ). The historical novel and sometimes even memoir, in the 20 th century, often closely resembled the detective novel, and this project attempts to account for why. Long before Hayden White and other late 20 th - century theorists of historical practice demonstrated how much historical writing owes to narrative conventions, writers such as Faulkner and Warren had anticipated those scholars’ claims. By foregrounding the interpretation necessary to any historical narrative, these works suggest that the way investigators identify evidence and decide what it means is controlled by the rhetorical demands of the stories they are planning to tell about what has happened and by the prior loyalties and training of the investigators. -

WLA Conference 2013 COVER

Mural of Queen Califia and her Amazons, Mark Hopkins Hotel in San Francisco – Maynard Dixon and Frank Von Sloun The name of California derives from the legend of Califia, the queen of an island inhabited by dark- skinned Amazons in a 1521 novel by Garci Ordóñez de Montalvo, Las Sergas de Esplandián. Califia has been depicted as the Spirit of California, and she often figures in the myth of California's origin, symbolizing an untamed and bountiful land prior to European settlement. California has been calling to the world ever since, as land of promise, dreams and abundance, but also often as a land of harsh reality. The 48th annual conference of the Western Literature Association welcomes you to Berkeley, California, on the marina looking out to the San Francisco Bay. This is a place as rich in history and myth as Queen Califia herself. GRATEFUL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS go to the following sponsors for their generous support of the 2013 Western Literature Conference: • The Redd Center for Western Studies • American Studies, UC Berkeley • College of Arts & Humanities, UC Berkeley • English Department, UC Berkeley SPECIAL THANKS go to: • The Doubletree by Hilton Hotel • Aileen Calalo, PSAV Presentation Services • The Assistants to the President: Samantha Silver and George Thomas, Registration Directors; and Alaska Quilici, Hospitality and Event Coordinator • Sabine Barcatta, Director of Operations, Western Literature Association • William Handley, Executive Secretary / Treasurer, Western Literature Association • Paul Quilici, Program Graphic Designer • Sara Spurgeon, Kerry Fine, and Nancy Cook • Kathleen Moran • The ConfTool Staff Registration/ Info Table ATM EMC South - Sierra Nevada Islands Ballroom (2nd floor) (1st floor) Amador El Dorado Yerba Buena Belvedere Island Mariposa Treasure Island Angel Island Quarter Deck Islands Foyer Building (5) EMC North Conference Center (2nd floor) (3rd floor) (4th floor) Berkeley Sacramento Restrooms California Guest Pass for Wireless Access: available in the Islands Ballroom area and Building 5 1. -

American Book Awards 2004

BEFORE COLUMBUS FOUNDATION PRESENTS THE AMERICAN BOOK AWARDS 2004 America was intended to be a place where freedom from discrimination was the means by which equality was achieved. Today, American culture THE is the most diverse ever on the face of this earth. Recognizing literary excel- lence demands a panoramic perspective. A narrow view strictly to the mainstream ignores all the tributaries that feed it. American literature is AMERICAN not one tradition but all traditions. From those who have been here for thousands of years to the most recent immigrants, we are all contributing to American culture. We are all being translated into a new language. BOOK Everyone should know by now that Columbus did not “discover” America. Rather, we are all still discovering America—and we must continue to do AWARDS so. The Before Columbus Foundation was founded in 1976 as a nonprofit educational and service organization dedicated to the promotion and dissemination of contemporary American multicultural literature. The goals of BCF are to provide recognition and a wider audience for the wealth of cultural and ethnic diversity that constitutes American writing. BCF has always employed the term “multicultural” not as a description of an aspect of American literature, but as a definition of all American litera- ture. BCF believes that the ingredients of America’s so-called “melting pot” are not only distinct, but integral to the unique constitution of American Culture—the whole comprises the parts. In 1978, the Board of Directors of BCF (authors, editors, and publishers representing the multicultural diversity of American Literature) decided that one of its programs should be a book award that would, for the first time, respect and honor excellence in American literature without restric- tion or bias with regard to race, sex, creed, cultural origin, size of press or ad budget, or even genre. -

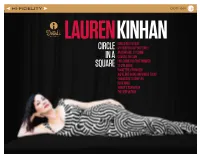

Circle in a Square CD Insert

HI-FIDELITY DOTI-1001 LAUREN KINHAN CIRCLE IN A SQUARE CIRCLE MY PAINTED LADY BUTTERFLY ANOTHER HILL TO CLIMB IN A CHASING THE SUN I’M LOOKIN’ FOR THAT NUMBER SQUARE TO LIVE OR DIE POCKETFUL OF HARLEM WE’RE NOT GOING ANYWHERE TODAY CHAUSSURE’S COMPLEX BEAR WALK VANITY’S PARAMOUR THE DEEP WITHIN LAUREN KINHAN CIRCLE IN A SQUARE CIRCLE IN A SQUARE CHASING THE SUN Music by Lauren Kinhan & Ada Rovatti Music by Lauren Kinhan Lyric by Lauren Kinhan Andy Ezrin, piano Andy Ezrin, Fender Rhodes David Finck, bass Ben Wittman, drums + percussion Ben Wittman, drums + percussion Will Lee, bass Aaron Heick, alto flute Randy Brecker, trumpet Romero Lubambo, guitar Lauren Kinhan, Marlon Saunders, Ella Marcus, backround vocals I’M LOOKIN’ FOR THAT NUMBER Music & Lyric by Lauren Kinhan MY PAINTED LADY BUTTERFLY Horn arrangement by Lauren Kinhan Music and Lyric by Lauren Kinhan Andy Ezrin, piano and B3 organ Andy Ezrin, piano David Finck, bass David Finck, bass Ben Wittman, drums Ben Wittman, drums Donny McCaslin, tenor saxophone Joel Frahm, Soprano Saxophone John Bailey, flugel horn ANOTHER HILL TO CLIMB TO LIVE OR DIE Music & Lyric by Lauren Kinhan Music & Lyric by Lauren Kinhan String quartet arrangement by Rob Mounsey Andy Ezrin, piano Andy Ezrin, piano David Finck, bass David Finck, bass Ben Wittman, drums + percussion Ben Wittman, drums Romero Lubambo, guitar Sara Caswell (1st violin), Joseph Brent (2nd violin), Lois Martin (viola), Jody Redhage (cello) POCKETFUL OF HARLEM BEAR WALK Music by Lauren Kinhan & Andy Ezrin Music by Jiro Yoshida, Lyric by -

Caswell Sisters

THE CASWELL SISTERS The riveting performances of the Caswell Sisters, vocalist Rachel and violinist Sara, are the culmination of years of working together. Their seamless sound combined with their unique interpretation of repertoire ranging from the “Great American Songbook” to contemporary jazz, including their own compositions, is propelled by arresting improvisation. Rachel and Sara co-lead the Caswell Sisters Quintet and have made such notable appearances as a weeklong After-Hours engagement at Dizzy’s Club Coca-Cola at Jazz at Lincoln Center in New York City and an enthusiastically-received set on the opening night concert of the inaugural Jazz Education Network (JEN) Conference. Their debut Caswell Sisters album Alive in the Singing Air (Turtle Ridge Records) featuring jazz pianist Fred Hersch was released in 2013 to rave reviews and was selected by jazz critic Thomas Cunniffe as one of the year’s “Best Vocal CDs” on Jazz History Online. In addition to the musical partnership Rachel and Sara have shared since childhood, their development and experience as individual artists play an equally important role in their musical careers. Rachel, a master of vocal improvisation and lyric interpretation, regularly performs with guitarist Dave Stryker and bassist Jeremy Allen, culminating in the release of her highly-praised 2015 CD For All I Know (Turtle Ridge Records), an album of duets with these two outstanding musicians. She has performed at clubs and festivals around the country and with big bands such as the Glenn Miller Orchestra and musicians the likes of John Blake, Jr., Ingrid Jensen, the Billy Taylor Trio, and Curtis Fuller. -

Érma Ensemble

ÉRMA ENSEMBLE MEMBERS LOTTE NURIA ADLER Lotte Nuria Adler (* 28th May 1998) discovered the mandolin for herself at the age of seven. From 2011 to 2015 she participated in the talent program of the Folkwang Music School Essen. Later, she has repeatedly taken master classes with Joseph Brent, Mike Marshall, Gertrud Weyhofen, Marga Wilden-Hüsgen, Markus Stockhausen and others. After graduating from high school in 2016, Lotte Nuria Adler took up her studies at Cologne Music College (Wuppertal branch) with Prof. Caterina Lichtenberg. At the same college she concurrently studies Elementary Music Pedagogy. Lotte Nuria Adler has frequently participated in both national and international competitions since 2008. As a child already, she had won numerous first prices and reached the maximum score at the federal competition of Jugend musiziert more than once. Participating in the most renowned international competitions for mandolin she has obtained a second prize at the 2nd International Solo Mandolin Competition Luxembourg in 2016 and the first price along with the audience award at the Yasuo-Kuwahara-Wettbewerb in 2018 where earlier she had already obtained the third price along with the audience award in 2015 at the age of 16. At the age of 13 Lotte Nuria Adler became concertmaster of the Plucked String Orchestra Düsseldorf. Regular guest performances with different orchestras from across the province have granted her entry to numerous concert houses such as Tonhalle, German Opera on the Rhine and Philharmonie Essen. In 2017, Lotte Nuria joined the «Studio Musikfabrik“, youth ensemble of the «Ensemble Musikfabrik». From an early age she has been attached to Contemporary Music. -

Nature and Spirit in the Novels of Louis Owens

Connected to the Land: Nature and Spirit in the Novels of Louis Owens Raymond Pierotti As the author was preparing this essay, he learned of the untimely and deeply sad passing of Louis Owens. As a result, what had originally been planned as a review of Peter LaLonde's book about Owens' novels was altered to serve as a tribute to Owens1 memory and to show why he should be regarded as one of the major voices in Indigenous literature. Abstract Many authors who have contributed significantly to Native American writing are mixed bloods, because such individuals are invariably the ones who will initially engage the dominant culture. The mixed cultural experiences and traditions of these individuals predispose them to working in art forms that do not arise from tribal cultural traditions. Louis Owens, a Choctaw-Cherokee and Irish writer and scholar was especially effective in presenting clear images of what it means to be of mixed blood. Owens evoked a sense of Indigenous tradition and identity as a means of coping with events taking place outside of tribal culture. One of his strengths was his ability to incorporate the physical landscape and the non-human elements of the community as vital presences into his writing. Owens also integrated the spirit world very effectively into his writing. To the Indigenous reader this means that elements that are important to 77 78 Raymond Pierotti Indigenous identity, but often ignored by most writers, including other Indian writers, are allowed to become important elements of the story. These concepts are explored with examples drawn from the five novels Owens published during his life. -

3344 Contemporary American Indian Fiction

1 Contemporary American Indian Fiction / Summer 2011 Dedicated to the memories of Lee Francis, James Welch, Louis Owens, Vine Deloria, Jr., Michael Dorris, Elaine Jahner, and Paula Gunn Allen English 3344-001 Office Hrs: T/Th 1:30-3; MWF by apt 405 CH Dr. Roemer Please schedule all appointments. MTWTH 10:30-12:30; Preston 300 Phone: 272-2729; e-mail: [email protected] Goals & Means 1. to introduce students to selected novels and short stories written since 1968 by authors with American Indian heritages and to resources for studying these texts [classes/readings/tapes/Internet, syllabus bibliography] 2. to discuss aesthetic, theoretical, ethical, and political issues raised by the texts (e.g., concepts of identity, place, gender and language; integrations of mainstream and non- mainstream cultures and oral and written literatures) [classes/exams/papers] 3. to examine in particular: (a) canon formation issues (first three novels); (b) redefinitions of representations of American history (second three novels); (c) trends in recent fiction (Howe, Sarris, Alexie, and readings in the course packet) 4. to enhance two types of writing skills: (a) a self-reflective reader-response exercise to explore how each student transforms texts into images and concepts meaningful to him or her [first paper]; (b) an evaluation of a critical article or chapter about one of the assigned texts (second paper) Assessment & Outcomes (See also the criteria for "Examinations," "Paper," and "Grading.”) By the end of the semester, students who have successfully completed the in- and out-of- class assignments should (1) know basic biographical and bibliographical information about each of the authors studied; (2) be able to discuss intelligently (a) significant issues raised in the works studied and (b) the general issues indicated in goal #2 above; (3) be able to articulate orally and in writing (a) explanations for their responses to selected works by Native American authors and (b) evaluations of relevant criticism. -

San Francisco Symphony and Michael Tilson Thomas Announce 2012-13 Season Concert Programs, Recordings, and Community Initiatives

SAN FRANCISCO SYMPHONY AND MICHAEL TILSON THOMAS ANNOUNCE 2012-13 SEASON CONCERT PROGRAMS, RECORDINGS, AND COMMUNITY INITIATIVES (Images of Michael Tilson Thomas, Renée Fleming, Lang Lang, Juraj Valcuha, and Khatia Buniatishvili available online in the 2012-2013 Press Kit) Orchestra’s 101st season highlights include Tilson Thomas-led explorations of music by Beethoven, Stravinsky, and enhanced concert experiences around Grieg’s Peer Gynt and Beethoven’s Missa solemnis MTT conducts the SFS in the first concert performances by an orchestra of Bernstein’s complete West Side Story Orchestra to perform two world premieres, three US premieres, three West Coast premieres, and 13 San Francisco Symphony premieres MTT leads premieres of new SFS commissions by Robin Holloway, Jörg Widmann and Samuel Carl Adams Soprano Renée Fleming and pianist András Schiff perform in Project San Francisco residencies; Schiff begins two-year exploration of Bach’s works for keyboard Distinguished guests include Joshua Bell, Pinchas Zukerman, Julia Fischer, Lang Lang, Yuja Wang, Marc- André Hamelin, Gil Shaham, Jonathan Biss, Yefim Bronfman, David Robertson, Vasily Petrenko, and Marek Janowski, with debuts by Vladimir Jurowski, Jaap van Zweden, Juraj Valcuha, Jean-Efflam Bavouzet, Michael Fabiano, and The Dmitri Pokrovsky Ensemble Great Performers Series features concerts by the Warsaw Philharmonic and Russian National Orchestra plus recitals by Itzhak Perlman, Gil Shaham, Renée Fleming with Susan Graham, and Matthias Goerne with Christoph Eschenbach MTT and Orchestra