Contexts and Perspectives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EC06-1255 List and Description of Named Cultivars in the Genus Penstemon Dale T

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Historical Materials from University of Nebraska- Extension Lincoln Extension 2006 EC06-1255 List and Description of Named Cultivars in the Genus Penstemon Dale T. Lindgren University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/extensionhist Lindgren, Dale T., "EC06-1255 List and Description of Named Cultivars in the Genus Penstemon" (2006). Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension. 4802. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/extensionhist/4802 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Extension at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. - CYT vert . File NeBrasKa s Lincoln EXTENSION 85 EC1255 E 'Z oro n~ 1255 ('r'lnV 1 List and Description of Named Cultivars in the Genus Penstemon (2006) Cooperative Extension Service Extension .circular Received on: 01- 24-07 University of Nebraska, Lincoln - - Libraries Dale T. Lindgren University of Nebraska-Lincoln 00IANR This is a joint publication of the American Penstemon Society and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension. We are grateful to the American Penstemon Society for providing the funding for the printing of this publication. ~)The Board of Regents oft he Univcrsit y of Nebraska. All rights reserved. Table -

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

Taylor's Residential Series™ Test Kits

Taylor’s Residential Series™ Test Kits INTRODUCTION aylor’s Residential Series™ test kits are designed for spa and pool owners who have low bather loads and test their water between visits from a service technician Tor trips to their pool supplies store. This series uses the same quality reagents as Taylor’s kits for professional analysts. Buyers have a choice of three progressively more sophisticated models: 3-Way, 6-Way, and 9-Way, as described below. Every Residential kit is available in our classic case—the solid blue, injection-molded plastic kit which is so durable it The K-1004 6-Way DPD kit monitors three variables that impact water can be refilled season after season. Tabs on every case make quality so problems can be detected and treated early, with less them easy to hang from hooks. expense. Residential kits feature .75 oz. reagents color-coded to 3-WAY (DPD) instructions; sanitizer values for both chlorine and bromine Free Chlorine .25–2.5 ppm testing; five sets of printed-color standards encased in Total Bromine .5–5 ppm plastic for longevity (calibrated to work with Taylor pH pH 6.8–8.2 reagents R-0014, R-0015, and R-0016); and molded fill English: K-1101 lines to ensure the correct sample size. Spanish: K-1101S Instructions are written in clear, nontechnical terms and Spanish version is available in a case pack of twelve (K-1101S-12) include pictograms for ease of following steps. Instruction 6-WAY (OT) cards printed on waterproof paper that resists fading and Total Chlorine .5–5 ppm tearing. -

CHAPTER THIRTY the AFFLUENT SOCIETY Objectives a Thorough Study of Chapter 30 Should Enable the Student to Understand: 1

CHAPTER THIRTY THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY Objectives A thorough study of Chapter 30 should enable the student to understand: 1. The strengths and weaknesses of the economy in the 1950s and early 1960s. 2. The changes in the American lifestyle in the 1 950s. 3. The significance of the Supreme Court’s desegregation decision and the early civil rights movement. 4. The characteristics of Dwight Eisenhower’s middle-of-the-road domestic policy. 5. The new elements of American foreign policy introduced by Secretary of State John Foster Dulles. 6. The causes and results of increasing United States involvement in the Middle East. 7. The sources of difficulties for the United States in Latin America. 8. The reasons for new tensions with the Soviet Union toward the end of the Eisenhower administration. Main Themes 1. That the technological, consumer-oriented society of the 1 950s was remarkably affluent and unified despite the persistence of a less privileged underclass and the existence of a small corps of detractors. 2. How the Supreme Court’s social desegregation decision of 1954 marked the beginning of a civil- rights revolution for American blacks. 3. How President Dwight Eisenhower presided over a business-oriented “dynamic conservatism” that resisted most new reforms without significantly rolling back the activist government programs born in the 1930s. 4. That while Eisenhower continued to allow containment by building alliances, supporting anticommunist regimes, maintaining the arms race, and conducting limited interventions, he also showed an awareness of American limitations and resisted temptations for greater commitments. Glossary 1. Third World A convenient way to refer to all the nations of the world besides the United States, Canada, the Soviet Union, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Israel, China, and the countries of Europe. -

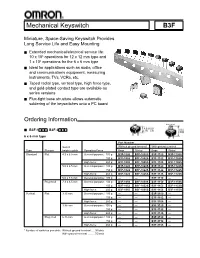

Mechanical Keyswitch B3F

Mechanical Keyswitch B3F Miniature, Space-Saving Keyswitch Provides Long Service Life and Easy Mounting ■ Extended mechanical/electrical service life: 10 x 106 operations for 12 x 12 mm type and 1 x 106 operations for the 6 x 6 mm type ■ Ideal for applications such as audio, office and communications equipment, measuring instruments, TVs, VCRs, etc. ■ Taped radial type, vertical type, high force type, and gold-plated contact type are available as series versions ■ Flux-tight base structure allows automatic soldering of the keyswitches onto a PC board Ordering Information Flat Projected ■ B3F-1■■■, B3F-3■■■ 6 x 6 mm type Part Number Switch Without ground terminal With ground terminal Type Plunger height x pitch Operating Force Bags Sticks* Bags Sticks* Standard Flat 4.3 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1000 B3F-1000S B3F-1100 B3F-1100S 150 g B3F-1002 B3F-1002S B3F-1102 B3F-1102S High-force: 260 g B3F-1005 B3F-1005S B3F-1105 B3F-1105S 5.0 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1020 B3F-1020S B3F-1120 B3F-1120S 150 g B3F-1022 B3F-1022S B3F-1122 B3F-1122S High-force: 260 g B3F-1025 B3F-1025S B3F-1125 B3F-1125S 5.0 x 7.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-1110 — Projected 7.3 x 6.5 mm General-purpose: 100 g B3F-1050 B3F-1050S B3F-1150 B3F-1150S 150 g B3F-1052 B3F-1052S B3F-1152 B3F-1152S High-force: 260 g B3F-1055 B3F-1055S B3F-1155 B3F-1155S Vertical Flat 3.15 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3100 — 150 g — — B3F-3102 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3105 — 3.85 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3120 — 150 g — — B3F-3122 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3125 — Projected 6.15 mm General-purpose: 100 g — — B3F-3150 — 150 g — — B3F-3152 — High-force: 260 g — — B3F-3155 — * Number of switches per stick: Without ground terminal ... -

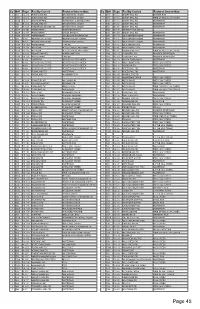

Bridge Index

Co Br# Page Facility Carried Featured Intersedtion Co Br# Page Facility Carried Featured Intersedtion 1 001 12 2-G RISING SUN RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 087 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD BURRIS RUN 1 001A 12 2-G RISING SUN RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 088 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD TRIB OF RED CLAY CREEK 1 001B 12 2-F KENNETT PIKE WATERWAY & ABANDON RR 1 089 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD. WATERWAY 1 002 9 12-G ROCKLAND RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 090 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD. WATERWAY 1 003 9 11-G THOMPSON BRIDGE RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 091 9 10-C SNUFF MILL RD. WATERWAY 1 004P 13 3-B PEDESTRIAN NORTHEAST BLVD 1 092 9 11-E KENNET PIKE (DE 52) 1 006P 12 4-G PEDESTRIAN UNION STREET 1 093 9 10-D SNUFF MILL RD WATERWAY 1 007P 11 8-H PEDESTRIAN OGLETOWN STANTON RD 1 096 9 11-D OLD KENNETT ROAD WATERWAY 1 008 9 9-G BEAVER VALLEY RD. BEAVER VALLEY CREEK 1 097 9 11-C OLD KENNETT ROAD WATERWAY 1 009 9 9-G SMITHS BRIDGE RD BRANDYWINE CREEK 1 098 9 11-C OLD KENNETT ROAD WATERWAY 1 010P 10 12-F PEDESTRIAN I 495 NB 1 099 9 11-C OLD KENNETT RD WATERWAY 1 011N 12 1-H SR 141NB RD 232, ROCKLAND ROAD 1 100 9 10-C OLD KENNETT RD. WATERWAY 1 011S 12 1-H SR 141SB RD 232, ROCKLAND ROAD 1 105 9 12-C GRAVES MILL RD TRIB OF RED CLAY CREEK 1 012 9 10-H WOODLAWN RD. -

UC Berkeley Berkeley Planning Journal

UC Berkeley Berkeley Planning Journal Title Economic Development and Housing Policy in Cuba Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9p00546t Journal Berkeley Planning Journal, 2(1) ISSN 1047-5192 Author Fields, Gary Publication Date 1985 DOI 10.5070/BP32113199 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND HOUSING POLICY IN CUBA Gary Fields Introduction Since the triumph of the Cuban Revolution in 1959, Cuba's economic development has been marked by efforts to achieve fo ur basic objectives: I) agrarian reform, including land redistribution, creation of state and cooperative farms, and agricultural crop diversification; 2) economic growth and industrial development, including the siting of new industries and employment opportunities in the countryside; 3) wealth and income redistribution from rich to poor citizens and from urban to rural areas; 4) provision of social services in all areas of the country, including nationwide literacy, access to medical care in the rural areas, and the creation of adequate and affordable housing nationwide. It is important to note that all of these objectives contain an emphasis on rural development. This emphasis was the result of decisions by Cuban economic planners to correct what had been perceived as the most serious ·negative consequence of the Island's economic past--the economic imbalance between town and coun try. 1 The dependence of the Cuban economy on sugar production, with its dramatic seasonal employment shifts, the control of the Island's sugar industry by American companies and the siphoning of sugar profits out of Cuba, the concentration in Havana of the wealth created primarily in the countryside, and the lack of economic opportunities and social services in the rural areas, were the main features of an economic and social system that had impoverished the rural population, creating a movement for change. -

Widsith Beowulf. Beowulf Beowulf

CHAPTER 1 OLD ENGLISH LITERATURE The Old English language or Anglo-Saxon is the earliest form of English. The period is a long one and it is generally considered that Old English was spoken from about A.D. 600 to about 1100. Many of the poems of the period are pagan, in particular Widsith and Beowulf. The greatest English poem, Beowulf is the first English epic. The author of Beowulf is anonymous. It is a story of a brave young man Beowulf in 3182 lines. In this epic poem, Beowulf sails to Denmark with a band of warriors to save the King of Denmark, Hrothgar. Beowulf saves Danish King Hrothgar from a terrible monster called Grendel. The mother of Grendel who sought vengeance for the death of her son was also killed by Beowulf. Beowulf was rewarded and became King. After a prosperous reign of some forty years, Beowulf slays a dragon but in the fight he himself receives a mortal wound and dies. The poem concludes with the funeral ceremonies in honour of the dead hero. Though the poem Beowulf is little interesting to contemporary readers, it is a very important poem in the Old English period because it gives an interesting picture of the life and practices of old days. The difficulty encountered in reading Old English Literature lies in the fact that the language is very different from that of today. There was no rhyme in Old English poems. Instead they used alliteration. Besides Beowulf, there are many other Old English poems. Widsith, Genesis A, Genesis B, Exodus, The Wanderer, The Seafarer, Wife’s Lament, Husband’s Message, Christ and Satan, Daniel, Andreas, Guthlac, The Dream of the Rood, The Battle of Maldon etc. -

Violence, Christianity, and the Anglo-Saxon Charms Laurajan G

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1-1-2011 Violence, Christianity, And The Anglo-Saxon Charms Laurajan G. Gallardo Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Gallardo, Laurajan G., "Violence, Christianity, And The Anglo-Saxon Charms" (2011). Masters Theses. 293. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/293 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. *****US Copyright Notice***** No further reproduction or distribution of this copy is permitted by electronic transmission or any other means. The user should review the copyright notice on the following scanned image(s) contained in the original work from which this electronic copy was made. Section 108: United States Copyright Law The copyright law of the United States [Title 17, United States Code] governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of "fair use," that use may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. -

Box Pack Price Guide Effective October 1, 2006 Table of Contents

Introducing Architecturally Inspired Collections Box Pack Price Guide effective October 1, 2006 Table of Contents KWIKSET ULTRAMAX SIGNATURES Metal INTERCONNECT Handlesets Metal Interconnect...................................................................... 26 Ashfield, Avalon, Amherst, Arlington, Chelsea, Hawthorne, Shelburne, Sheridan, Wellington .................... 2-6 RESIDENTIAL/LIGHT COMMERCIAL Baldwin Handlesets with K-Keyway ...................................... 7 Kingston ................................................................................ 27 Knobs Abbey, Circa, Hancock, Laurel ................................................ 8 LATCHES, STRIKES & CYLINDERS Deadlatch Plain Latches, 6-Way Latches .............................. 28-29 Levers 580, 780, 970, 980S, 660 Series Deadbolt Latches ............... 30-31 Brooklane, Commonwealth, Pembroke .................................. 9 Strikes & Boxes ...................................................................... 32-34 Deadbolts Cylinders................................................................................. 35-37 980S Series, 780 Series ....................................................... 10 KEYING KWIKSET MAXIMUM SECURITY Keys & Key Blanks ...................................................................... 38 Handlesets Keying Charges and Supplies ............................................... 38-40 Gibson ................................................................................... 12 Sonoma ............................................................................... -

Cain's Kin and Abel's Blood: Beowulf 1361-4

Opticon1826, Issue 9, Autumn 2010 CAIN’S KIN AND ABEL’S BLOOD: BEOWULF 1361-4 By Michael D.J. Bintley Amongst the various texts which are thought to have influenced the depiction of Grendel’s mere in Beowulf, the possibility has not yet been considered that the poet also drew upon a tradition associated with Grendel’s descent from Cain, also to be found in the composite Genesis poem of the Junius manuscript (Oxford, Bodleian Library MS Junius 11, SC 5123), and Aldhelm’s Carmen de virginitate. This connection only becomes apparent upon closer examination of the woodland grove overhanging the refuge in Grendel’s fens. Of the many trees that appear in Old English literature, few can be as sinister as these. These trees contribute memorably to Hrothgar’s description of the mere: Nis þæt feor heonon milgemearces þæt se mere standeð; ofer þæm hongiað hrinde bearwas, wudu wyrtum fæst wæter oferhelmað. It is not far hence in a measure of miles that the mere stands; over it hang frosty trees, a wood fast in its roots overshadows the water. (Beowulf 1361-4)1 These trees appear once again in the description of the journey to the mere following the attack by Grendel’s mother: Ofereode þa æþelinga bearn steap stanhliðo, stige nearwe, enge anpaðas, uncuð gelad, neowle næssas, nicorhusa fela; he feara sum beforan gengde wisra monna wong sceawian, oþ þæt he færinga fyrgenbeamas ofer harne stan helonian funde wynleasne wudu; wæter under stod dreorig on gedrefed. Then went those sons of nobles over steep and stony slopes, thin ascending paths, narrow single tracks, unknown ways, precipitous cliffs, many dwellings of water-monsters. -

Overlapping Oppositions in Beowulf, Guthlac A, and the Old English Physiologus

Overlapping Oppositions in Beowulf, Guthlac A, and the Old English Physiologus A Thesis submitted to the Graduate School Valdosta State University in partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ENGLISH in the Department of English of the College of Arts & Sciences May 2016 Mary Nicole “Nikki” Roop BA, Georgia Southern University, 2012 © Copyright 2016 Mary Nicole Roop All Rights Reserved This thesis, “Overlapping Oppositions in Beowulf, Guthlac A, and the Old English Physiologus,” by Nikki Roop, is approved by: Thesis __________________________________ Chair Maren Clegg-Hyer, Ph.D. Associate Professor of English Committee __________________________________ Member Jane M. Kinney, Ph.D. Professor of English __________________________________ Viki Soady, Ph.D. Professor of Modern and Classical Languages Dean of the Graduate School __________________________________ James T. LaPlant, Ph. D Professor of Political Science FAIR USE This thesis is protected by the Copyright Laws of the United States (Public Law 94-553, revised in 1976). Consistent with fair use as defined in the Copyright Laws, brief quotations from this material are allowed with proper acknowledgement. Use of the material for financial gain without the author’s expressed written permission is not allowed. DUPLICATION I authorize the Head of Interlibrary Loan or the Head of Archives at the Odum Library at Valdosta State University to arrange for duplication of this thesis for educational or scholarly purposes when so requested by a library user. The duplication shall be at the user’s expense. Signature _______________________________________________ I refuse permission for this thesis to be duplicated in whole or in part. Signature ________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Binaries in literature depict people, ideas, and actions that are in opposition to each other: good and evil; life and death; hero and villain.