Dance Interrogations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10.9 De Jesus Precarious Girlhood Dissertation Draft

! ! "#$%&#'()*!+'#,-((./!"#(0,$1&2'3'45!6$%(47'5)#$.!8#(9$*!(7!:$1'4'4$!;$<$,(91$42! '4!"(*2=>??@!6$%$**'(4&#A!B'4$1&! ! ! ;$*'#C$!.$!D$*)*! ! ! ! ! E!8-$*'*! F4!2-$!! G$,!H(99$4-$'1!I%-((,!(7!B'4$1&! ! ! ! ! "#$*$42$.!'4!"'&,!:),7',,1$42!(7!2-$!6$J)'#$1$42*! :(#!2-$!;$5#$$!(7! ;(%2(#!(7!"-',(*(9-A!K:',1!&4.!G(<'45!F1&5$!I2).'$*L! &2!B(4%(#.'&!M4'<$#*'2A! G(42#$&,N!O)$0$%N!B&4&.&! ! ! ! ! ! P%2(0$#!>?Q@! ! R!;$*'#C$!.$!D$*)*N!>?Q@ ! ! CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Desirée de Jesus Entitled: Precarious Girlhood: Problematizing Reconfigured Tropes of Feminine Development in Post-2009 Recessionary Cinema and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Film and Moving Image Studies complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: Chair Dr. Lorrie Blair External Examiner Dr. Carrie Rentschler External to Program Dr. Gada Mahrouse Examiner Dr. Rosanna Maule Examiner Dr. Catherine Russell Thesis Supervisor Dr. Masha Salazkina Approved by Dr. Masha Salazkina Chair of Department or Graduate Program Director December 4, 2019 Dr. Rebecca Duclos Dean Faculty of Fine Arts ! ! "#$%&"'%! ()*+,)-./0!1-)23..45!().62*7,8-9-:;!&*+.:<-;/)*4!%).=*0!.<!>*7-:-:*!?*@*2.=7*:8!-:! (.08ABCCD!&*+*00-.:,)E!'-:*7,! ! ?*0-)F*!4*!G*0/0! '.:+.)4-,!H:-@*)0-8EI!BCJD! ! !"##"$%&'()*+(,--.(/#"01#(2+3+44%"&5()*+6+($14(1(4%'&%7%31&)(3*1&'+(%&()*+(3%&+81)%3(9+:%3)%"&( -

Prospectus 19/ 20 Trinity Laban Conservatoire Of

PROSPECTUS 19/20 TRINITY LABAN CONSERVATOIRE OF MUSIC & DANCE CONTENTS 3 Principal’s Welcome 56 Music 4 Why You Should #ChooseTL 58 Performance Opportunities 6 How to #ExperienceTL 60 Music Programmes FORWARD 8 Our Home in London 60 Undergraduate Programmes 10 Student Life 62 Postgraduate Programmes 64 Professional Development Programmes 12 Accommodation 13 Students' Union 66 Academic Studies 14 Student Services 70 Music Departments 16 International Community 70 Music Education THINKING 18 Global Links 72 Composition 74 Jazz Trinity Laban is a unique partnership 20 Professional Partnerships 76 Keyboard in music and dance that is redefining 22 CoLab 78 Strings the conservatoire of the 21st century. 24 Research 80 Vocal Studies 82 Wind, Brass & Percussion Our mission: to advance the art forms 28 Dance 86 Careers in Music of music and dance by bringing together 30 Dance Staff 88 Music Alumni artists to train, collaborate, research WELCOME 32 Performance Environment and perform in an environment of 98 Musical Theatre 34 Transitions Dance Company creative and technical excellence. 36 Dance Programmes 106 How to Apply 36 Undergraduate Programmes 108 Auditions 40 Masters Programmes 44 Diploma Programmes 110 Fees, Funding & Scholarships 46 Careers in Dance 111 Admissions FAQs 48 Dance Alumni 114 How to Find Us Trinity Laban, the UK’s first conservatoire of music and dance, was formed in 2005 by the coming together of Trinity College of Music and Laban, two leading centres of music and dance. Building on our distinctive heritage – and our extensive experience in providing innovative education and training in the performing arts – we embrace the new, the experimental and the unexpected. -

Download the Creative Industries Strategy

Creative Industries Strategy An industry-led Strategy produced by the Department for Innovation and Skills, in collaboration with Department for Trade and Investment and various industry representatives. 2020 GROWTH STATE Spider-Man: Far From Home - Visual effects by Rising Sun Pictures. © & TM 2019 MARVEL. © 2019 CTMG. All Rights Reserved. Credit: Rising Sun Pictures. The Department for Innovation and Skills acknowledges Aboriginal people as the state’s first peoples and Nations of South Australia. We recognise and respect their cultural connections as the traditional owners and occupants of the land and waters of South Australia, and that they have and continue to maintain a unique and irreplaceable contribution to the state. Ngarrindjeri designer Jordan Lovegrove at Ochre Dawn. Credit: Ochre Dawn Creative Industries. CREATIVE INDUSTRIES Strategy Table of Contents Message from the Minister 4 Message from the Creative Industries Ministerial Advisory Group 5 Section 1: Background 6 Executive summary 6 Growth State 6 The Creative Industries Strategy 7 What are the creative industries? 9 Advertising and Communication Design 11 Broadcasting: TV, Radio and Podcasts 11 Design 12 Design – Urban, Architecture, Interior and Landscape 12 Design – Industrial and Product 13 Fashion 14 Festivals (Creative and Cultural) 15 Music 18 Performing Arts 21 Visual Arts and Craft 21 Screen 22 Screen – TV and Film Production 23 Screen – Post Production, Digital and Visual Effects (PDV) 24 Screen - Game Development 25 Writing and Publishing 26 Technology and -

Age Appropriate? Sundance’S Women Filmmakers Come Next

Swarthmore College Works Film & Media Studies Faculty Works Film & Media Studies Winter 2013 Age Appropriate? Sundance’s Women Filmmakers Come Next Patricia White Swarthmore College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-film-media Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Patricia White. (2013). "Age Appropriate? Sundance’s Women Filmmakers Come Next". Film Quarterly. Volume 67, Issue 2. 80-84. DOI: 10.1525/fq.2014.67.2.80 https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-film-media/51 This work is brought to you for free by Swarthmore College Libraries' Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Film & Media Studies Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Age Appropriate? Sundance’s Women Filmmakers Come Next Patricia White When Desiree´ Akhavan took the stage for the premiere of with terms like ‘‘secretarial pools’’ and ‘‘coeds’’, has come her film Appropriate Behavior in the Sundance Film Festi- back to brand the artistic self-examination of the Title IX val’s ‘‘Next’’ section, she remarked that while many young generation. women fantasize about their wedding day, her lifelong One reason of course is that ‘‘girls’’ can be sexy. This dream was to screen a feature film at Sundance. ‘‘Welcome year’s ‘‘Next’’ section proved to be so as well. Appropriate to my wedding!’’ the first-time filmmaker greeted the Behavior is one of three raunchy comedies about under- crowd. Her marriage detour resonated in part because she employed young women in New York featured in the identifies as bisexual and was speaking in Utah, where just section for (low-budget) digital filmmaking and innovative a few months before, the right of same-sex couples to marry storytelling. -

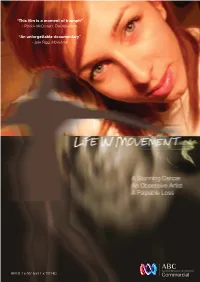

Life in Movement Flier.Pdf (Format PDF / 593 KB )

Life in Movement A4 flyer.xpd:Layout 1 18/9/12 2:49 PM Page 1 “This film is a moment of triumph” - Patrick McDonald, The Advertiser “An unforgettable documentary” - Julie Rigg, Movietime ARTS 1 x 56’ and 1 x 79’ HD Life in Movement A4 flyer.xpd:Layout 1 18/9/12 2:49 PM Page 2 ARTS 1 x 56’ and HD 1 x 79’ “To see [Tanja’s] process, of creating art through these videos and the interviews they had with her – it’s a unique documentary. I’ve rarely seen an artistic process captured in film like this – it’s so enlightening, so inspirational. You see the commitment that goes into it. I was left asking myself: ‘Man, am I doing everything I possibly can – am I giving my all in everything I do?’ It was one of the great strengths of the film. I was very moved by it all.” Trevor Groth Director of Programming, Sundance Film Festival In 2007 the Sydney Dance Company appointed 29-year-old choreographer Tanja Liedtke as their first new artistic director in 30 years. However before she could take up the position, she was struck and killed by a truck in the middle of the night. Admired internationally as a dancer and celebrated for her fresh choreographic voice, she was known as a dedicated artist, intelligent, funny and generous. Eighteen months after Tanja’s death her collaborators embark on a world tour of her work, and in the process they must deal with their grief and explore the reasons for her death. -

DV8 and Lloyd Newson Topic Exploration Pack September 2015

Performance Studies A LEVEL Performance Studies: DV8 and Lloyd Newson Topic Exploration Pack September 2015 www.ocr.org.uk Topic Exploration Pack We will inform centres about any changes to the specification. We will also publish changes on our website. The latest version of our specification will always be the one on our website (www.ocr.org.uk) and this may differ from printed versions. Copyright © 2015 OCR. All rights reserved. Copyright OCR retains the copyright on all its publications, including the specifications. However, registered centres for OCR are permitted to copy material from this specification booklet for their own internal use. Oxford Cambridge and RSA Examinations is a Company Limited by Guarantee. Registered in England. Registered company number 3484466. Registered office: 1 Hills Road Cambridge CB1 2EU OCR is an exempt charity. 2 www.ocr.org.uk AS Level Performance Studies Contents DV8 and Lloyd Newson................................................................................................................... 4 Lesson One .................................................................................................................................... 7 Lesson Two .................................................................................................................................... 8 Lesson Three .................................................................................................................................. 9 This activity offers an opportunity for English skills development. Version -

Social Inclusion Open Access Journal | ISSN: 2183-2803

Social Inclusion Open Access Journal | ISSN: 2183-2803 Volume 4, Issue 4 (2016) HumanityHumanity asas aa ContestedContested Concept:Concept: RelationsRelations betweenbetween DisabilityDisability andand ‘Being‘Being Human’Human’ Editors Paul van Trigt, Alice Schippers and Jacqueline Kool Social Inclusion, 2016, Volume 4, Issue 4 Humanity as a Contested Concept: Relations between Disability and ‘Being Human’ Published by Cogitatio Press Rua Fialho de Almeida 14, 2º Esq., 1070-129 Lisbon Portugal Academic Editors Paul van Trigt, Leiden University, The Netherlands Alice Schippers, Disability Studies in Nederland, The Netherlands Jacqueline Kool, Disability Studies in Nederland, The Netherlands Available online at: www.cogitatiopress.com/socialinclusion This issue is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY). Articles may be reproduced provided that credit is given to the original and Social Inclusion is acknowledged as the original venue of publication. Table of Contents Humanity as a Contested Concept: Relations between Disability and ‘Being Human’ Paul van Trigt, Jacqueline Kool and Alice Schippers 125–128 The Value of Inequality Gustaaf Bos and Doortje Kal 129–139 “I Am Human Too!” ‘Probeerruimte’ as Liminal Spaces in Search of Recognition Fiona MacLeod Budge and Harry Wels 140–149 Weighing Posthumanism: Fatness and Contested Humanity Sofia Apostolidou and Jules Sturm 150–159 Differences in Itself: Redefining Disability through Dance Carolien Hermans 160–167 Challenging Standard Concepts of ‘Humane’ -

1927/28 - 2007 Гг

© Роман ТАРАСЕНКО. г. Мариуполь 2008г. Украина. [email protected] Лауреаты премии Американской Академии Киноискусства «ОСКАР». 1927/28 - 2007 гг. 1 Содержание Наменование стр Кратко о премии………………………………………………………. 6 1927/28г……………………………………………………………………………. 8 1928/29г……………………………………………………………………………. 9 1929/30г……………………………………………………………………………. 10 1930/31г……………………………………………………………………………. 11 1931/32г……………………………………………………………………………. 12 1932/33г……………………………………………………………………………. 13 1934г……………………………………………………………………………….. 14 1935г……………………………………………………………………………….. 15 1936г……………………………………………………………………………….. 16 1937г……………………………………………………………………………….. 17 1938г……………………………………………………………………………….. 18 1939г……………………………………………………………………………….. 19 1940г……………………………………………………………………………….. 20 1941г……………………………………………………………………………….. 21 1942г……………………………………………………………………………….. 23 1943г……………………………………………………………………………….. 25 1944г……………………………………………………………………………….. 27 1945г……………………………………………………………………………….. 29 1946г……………………………………………………………………………….. 31 1947г……………………………………………………………………………….. 33 1948г……………………………………………………………………………….. 35 1949г……………………………………………………………………………….. 37 1950г……………………………………………………………………………….. 39 1951г……………………………………………………………………………….. 41 2 1952г……………………………………………………………………………….. 43 1953г……………………………………………………………………………….. 45 1954г……………………………………………………………………………….. 47 1955г……………………………………………………………………………….. 49 1956г……………………………………………………………………………….. 51 1957г……………………………………………………………………………….. 53 1958г……………………………………………………………………………….. 54 1959г……………………………………………………………………………….. 55 1960г………………………………………………………………………………. -

New Feature from Scott Hicks Leads the Best of Australian Film at Adelaide Film Festival 2015 Highlights Announced Today

Wednesday August 12, 2015 NEW FEATURE FROM SCOTT HICKS LEADS THE BEST OF AUSTRALIAN FILM AT ADELAIDE FILM FESTIVAL 2015 HIGHLIGHTS ANNOUNCED TODAY A premiere feature documentary from Academy Award-winning director Scott Hicks, a new Australian film starring Anthony LaPaglia, Justine Clarke and John Clarke, directorial feature debuts from Bangarra Dance Theatre’s Stephen Page and Windmill Theatre Company’s Rosemary Myers and the red carpet screening of Jocelyn Moorhouse’s anticipated Australian film The Dressmaker are just some of the highlights that will feature at this year’s Adelaide Film Festival. Festival Creative Director Amanda Duthie today announced key highlights, ahead of the full program reveal next month and was thrilled to announce that Hicks’ documentary Highly Strung will have its world premiere and open the Festival, when it returns to Adelaide October 15-25. Highly Strung will screen at Her Majesty’s Theatre with a red carpet event, with Hicks in attendance. It joins the Adelaide-made dramedy feature A Month of Sundays, starring LaPaglia and directed by Matt Saville; Spear, a new work from Bangarra’s Stephen Page; Girl Asleep, filmed in Adelaide from director Rosemary Myers and featuring rising star Tilda Cobham-Hervey; and the Sundance Film Festival hit, Sam Klemke’s Time Machine, from Adelaide director Matthew Bate. Ms Duthie was also pleased to announce the Adelaide Film Festival red carpet screening of The Dressmaker, from director Jocelyn Moorhouse, and starring Kate Winslet, Judy Davis, Liam Hemsworth and Adelaide’s Sarah Snook – on October 16, at Her Majesty’s Theatre. Ticketing is now open for all titles released today. -

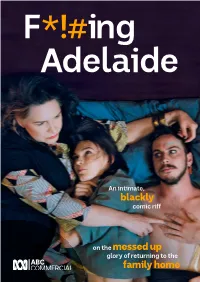

Fingadelaide Flyer.Pdf (Format PDF / 2 MB )

F*!#ing Adelaide An intimate, blackly comic riff on the messed up glory of returning to the family home AN INTIMATE, BLACKLY COMIC RIFF ON THE MESSED UP GLORY OF RETURNING TO THE FAMILY HOME HD 6 x 15’ Closer Productions Premiering at the Adelaide Film Festival and Series Mania France and starring Tilda Cobham-Hervey (Hotel Mumbai, I am Woman), F*!#ing Adelaide is a darkly comedic look at the theatrical, obsessive, self-centred, delightful people who make up the Wallace-Donaldson family – and the city they call home. Adelaide is a place Eli (Brendan Maclean, The Great Gatsby) said he’d only return to for Christmases and funerals. But now, at 28, Eli is not the success his older sister promised he would be. His autotuned show at a Sydney pub draws crowds he can count on one hand and his ex-boyfriend has kicked him out of the apartment because he owes him three month’s rent. So, when his mother Maude (Pamela Rabe, Wentworth) asks him back to help clean up their family home, a defeated Eli finds himself on a plane back to Adelaide, hoping to score a bed to sleep in. Unfortunately for Eli, the house is full to the brim as his big sister has returned with her family. When mum reveals to all that she’s selling their home, the family is shocked, confused, and demanding answers – but poor, exhausted Eli is still stuck on the couch. Featuring an outstanding cast, including AACTA Award nominee Kate Box (Rake), Beau Travis-Williams (Angry Boys) and Audrey Mason-Hyde (52 Tuesdays). -

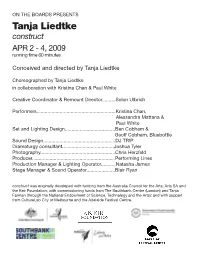

Tanja Liedtke Construct APR 2 - 4, 2009 Running Time 60 Minutes

ON THE BOARDS PRESENTS Tanja Liedtke construct APR 2 - 4, 2009 running time 60 minutes Conceived and directed by Tanja Liedtke Choreographed by Tanja Liedtke in collaboration with Kristina Chan & Paul White Creative Coordinator & Remount Director..........Solon Ulbrich Performers..........................................................Kristina Chan, Alessandra Mattana & Paul White Set and Lighting Design.....................................Ben Cobham & Geoff Cobham, Bluebottle Sound Design.....................................................DJ TR!P Dramaturgy consultant......................................Joshua Tyler Photography.......................................................Chris Herzfeld Producer.............................................................Performing Lines Production Manager & Lighting Operator...........Natasha James Stage Manager & Sound Operator.....................Blair Ryan construct was originally developed with funding from the Australia Council for the Arts, Arts SA and the Keir Foundation; with commissioning funds from The Southbank Centre (London) and Tanja Farman (through the National Endowment of Science, Technology and the Arts); and with support from CultureLab City of Melbourne and the Adelaide Festival Centre. A note from Solon Ulbrich, Creative Coordinator for construct It is a true pleasure to bring construct to On the Boards. I am very proud to see Tanja's engaging dance theatre at this adventurous and inspiring venue. construct was Tanja's final work, and all involved cherish this opportunity to share her captivating ideas, clearly expressed in the language of dance. The creative process for this work forged an ongoing creative relationship with the stunning original cast of collaborators you see performing on this tour. I am personally indebted to the dancers for their dedication and commitment to Tanja's vision. My thanks also to Fenn Gordon and Performing Lines, our producers, Lane and all the team at On the Boards, whose tireless ongoing efforts make it possible to share Tanja's work with you. -

Redefining Disability Through Dance

Social Inclusion (ISSN: 2183–2803) 2016, Volume 4, Issue 4, Pages 160–167 DOI: 10.17645/si.v4i4.699 Article Differences in Itself: Redefining Disability through Dance Carolien Hermans Art and Economics, Utrecht School of the Arts, 3500 BM Utrecht, The Netherlands; E-Mail: [email protected] Submitted: 21 June 2016 | Accepted: 30 August 2016 | Published: 10 November 2016 Abstract This paper brings together two different terms: dance and disability. This encounter between dance and disability might be seen as an unusual, even conflicting, one since dance is traditionally dominated by aesthetic virtuosity and perfect, ideal- ized bodies which are under optimized bodily control. However, recently there has been a growing desire within dance com- munities and professional dance companies to challenge binary thinking (beautiful-ugly, perfect-imperfect, valid-invalid, success-failure) by incorporating an aesthetic of difference. The traditional focus of dance on appearance (shape, tech- nique, virtuosity) is replaced by a focus on how movement is connected to a sense of self. This notion of the subjective body not only applies to the dancer’s body but also to disabled bodies. Instead of thinking of a body as a thing, an object (Körper) that is defined by its physical appearance, dance is more and more seduced by the body as we sense it, feel it and live it (Leib). This conceptual shift in dance is illustrated by a theoretical analysis of The Cost of Living, a dance film produced by DV8. Keywords dance; difference in itself; disability; Körper; Leib; lived body; lived experience Issue This article is part of the issue “Humanity as a Contested Concept: Relations between Disability and ‘Being Human’”, edited by Paul van Trigt (Leiden University, The Netherlands), Alice Schippers (Disability Studies in Nederland, The Netherlands) and Jacqueline Kool (Disability Studies in Nederland, The Netherlands).