Raploch Stories: Continuity and Innovation for Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fnh Journal Vol 28

the Forth Naturalist and Historian Volume 28 2005 Naturalist Papers 5 Dunblane Weather 2004 – Neil Bielby 13 Surveying the Large Heath Butterfly with Volunteers in Stirlingshire – David Pickett and Julie Stoneman 21 Clackmannanshire’s Ponds – a Hidden Treasure – Craig Macadam 25 Carron Valley Reservoir: Analysis of a Brown Trout Fishery – Drew Jamieson 39 Forth Area Bird Report 2004 – Andre Thiel and Mike Bell Historical Papers 79 Alloa Inch: The Mud Bank that became an Inhabited Island – Roy Sexton and Edward Stewart 105 Water-Borne Transport on the Upper Forth and its Tributaries – John Harrison 111 Wallace’s Stone, Sheriffmuir – Lorna Main 113 The Great Water-Wheel of Blair Drummond (1787-1839) – Ken MacKay 119 Accumulated Index Vols 1-28 20 Author Addresses 12 Book Reviews Naturalist:– Birds, Journal of the RSPB ; The Islands of Loch Lomond; Footprints from the Past – Friends of Loch Lomond; The Birdwatcher’s Yearbook and Diary 2006; Best Birdwatching Sites in the Scottish Highlands – Hamlett; The BTO/CJ Garden BirdWatch Book – Toms; Bird Table, The Magazine of the Garden BirthWatch; Clackmannanshire Outdoor Access Strategy; Biodiversity and Opencast Coal Mining; Rum, a landscape without Figures – Love 102 Book Reviews Historical–: The Battle of Sheriffmuir – Inglis 110 :– Raploch Lives – Lindsay, McKrell and McPartlin; Christian Maclagan, Stirling’s Formidable Lady Antiquary – Elsdon 2 Forth Naturalist and Historian, volume 28 Published by the Forth Naturalist and Historian, University of Stirling – charity SCO 13270 and member of the Scottish Publishers Association. November, 2005. ISSN 0309-7560 EDITORIAL BOARD Stirling University – M. Thomas (Chairman); Roy Sexton – Biological Sciences; H. Kilpatrick – Environmental Sciences; Christina Sommerville – Natural Sciences Faculty; K. -

PAC Report Sets out the Pre-Application Consultation That Has Been Carried out in Accordance with The

Ambassador LB Holdings LLP June 2020 Craigforth Campus, Stirling Pre-Application Consultation Report savills.co.uk Craigforth Campus, Stirling Pre-Application Consultation Report Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Statutory Consultation Requirements 3 3. Consultation Undertaken 6 4. Feedback from the Consultation Event 7 5. Conclusions 11 Appendices: Appendix 1 – Submitted PAN Appendix 2 – Email to Community Councils and Councillors containing PAN Appendix 3 – PAN Registration Letter Appendix 4 – Newspaper Press Advert Appendix 5 – Newspaper Press Article Appendix 6 – Media Coverage Appendix 7 – Public Event Feedback Form Appendix 8 – Public Event Display Boards Ambassador LB Holdings LLP June 2020 Craigforth Campus, Stirling Pre-Application Consultation Report 1. Introduction The PPiP Submission 1.1. This Pre-Application Consultation (PAC) Report has been prepared on behalf of Ambassador LB Holdings LLP (‘the Applicant’) in support of an application to Stirling Council (SC) for Planning Permission in Principle (PPiP) for offices, retail, leisure, public houses, restaurants, residential, hotel, care home, nursery, car parking landscaping and associated infrastructure on land at Craigforth Campus, Stirling (ePlanning Reference: 100273242-001). 1.2. The proposals represent the culmination of an in depth assessment of the Craigforth Campus and its future role within Stirling and beyond. The resultant vision seeks to deliver a viable and vibrant mixed use campus which creates a regional employment, leisure and residential destination at Craigforth. 1.3. The Site offers an exciting opportunity for expanding and enhancing upon the existing facilities to deliver a new active business campus with improved amenities, public realm and upgraded accessibility with additional employment opportunities for the wider community. -

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland a study © Adrienne Clare Scullion Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD to the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Glasgow. March 1992 ProQuest Number: 13818929 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818929 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Frontispiece The Clachan, Scottish Exhibition of National History, Art and Industry, 1911. (T R Annan and Sons Ltd., Glasgow) GLASGOW UNIVERSITY library Abstract This study investigates the cultural scene in Scotland in the period from the 1880s to 1939. The project focuses on the effects in Scotland of the development of the new media of film and wireless. It addresses question as to what changes, over the first decades of the twentieth century, these two revolutionary forms of public technology effect on the established entertainment system in Scotland and on the Scottish experience of culture. The study presents a broad view of the cultural scene in Scotland over the period: discusses contemporary politics; considers established and new theatrical activity; examines the development of a film culture; and investigates the expansion of broadcast wireless and its influence on indigenous theatre. -

Platform for Success: Final Report of the Scottish Broadcasting Commission

PLATFORM FOR SUCCESS Final report of the Scottish Broadcasting Commission PLATFORM FOR SUCCESS Final report of the Scottish Broadcasting Commission © Crown copyright 2008 ISBN: 978-0-7559-5845-0 The Scottish Government St Andrew’s House Edinburgh EH1 3DG Produced for the Scottish Broadcasting Commission by RR Donnelley B57086 Published by the Scottish Government, September, 2008 Further copies are available from Blackwell's Bookshop 53 South Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1YS Scottish Broadcasting Commission : 01 CONTENTS Foreword 2 Executive Summary 3 Chapter 1 Introduction 13 Chapter 2 Our Vision for Scottish Broadcasting 15 Chapter 3 Serving Audiences and Society 19 Chapter 4 A Network for Scotland 32 Chapter 5 Broadcasting and the Creative Economy 39 Chapter 6 Delivering the Future 51 Annex 56 02 : Scottish Broadcasting Commission FOREWORD In its short existence, the Scottish Broadcasting Commission has triggered a wide-ranging and frequently passionate debate about the future of the industry and the services it provides to audiences in Scotland. We intended from the beginning to make an impact which would lead to action, and there have been some encouraging early results in the form of new commitments from the broadcasters. But this is only a start. In publishing our final report and recommendations, we hope and expect that the debate will become even more visible and audible – with particular focus on the key opportunities and challenges we have identified in broadcasting and the new digital platforms. What has been refreshing is the extent to which both the industry and its audiences are at least as excited about the future as they are critical of some of the weaknesses of the past and present. -

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Migrating Minds

Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies Volume 5: Issue 1 Migrating Minds AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies, University of Aberdeen JOURNAL OF IRISH AND SCOTTISH STUDIES Volume 5, Issue 1 Autumn 2011 Migrating Minds Published by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen in association with The universities of the The Irish-Scottish Academic Initiative ISSN 1753-2396 Printed and bound in Great Britain by CPI Antony Rowe, Chippenham and Eastbourne Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies General Editor: Cairns Craig Issue Editor: Paul Shanks Associate Editor: Michael Brown Editorial Advisory Board: Fran Brearton, Queen’s University, Belfast Eleanor Bell, University of Strathclyde Ewen Cameron, University of Edinburgh Sean Connolly, Queen’s University, Belfast Patrick Crotty, University of Aberdeen David Dickson, Trinity College, Dublin T. M. Devine, University of Edinburgh David Dumville, University of Aberdeen Aaron Kelly, University of Edinburgh Edna Longley, Queen’s University, Belfast Peter Mackay, Queen’s University, Belfast Shane Alcobia-Murphy, University of Aberdeen Ian Campbell Ross, Trinity College, Dublin Graham Walker, Queen’s University, Belfast International Advisory Board: Don Akenson, Queen’s University, Kingston Tom Brooking, University of Otago Keith Dixon, Université Lumière Lyon 2 Marjorie Howes, Boston College H. Gustav Klaus, University of Rostock Peter Kuch, University of Otago Graeme Morton, University of Guelph Brad Patterson, Victoria University, Wellington Matthew Wickman, Brigham Young David Wilson, University of Toronto The Journal of Irish and Scottish Studies is a peer reviewed journal published twice yearly in autumn and spring by the AHRC Centre for Irish and Scottish Studies at the University of Aberdeen. -

The Gazetteer for Scotland Guidebook Series

The Gazetteer for Scotland Guidebook Series: Stirling Produced from Information Contained Within The Gazetteer for Scotland. Tourist Guide of Stirling Index of Pages Introduction to the settlement of Stirling p.3 Features of interest in Stirling and the surrounding areas p.5 Tourist attractions in Stirling and the surrounding areas p.9 Towns near Stirling p.15 Famous people related to Stirling p.18 Further readings p.26 This tourist guide is produced from The Gazetteer for Scotland http://www.scottish-places.info It contains information centred on the settlement of Stirling, including tourist attractions, features of interest, historical events and famous people associated with the settlement. Reproduction of this content is strictly prohibited without the consent of the authors ©The Editors of The Gazetteer for Scotland, 2011. Maps contain Ordnance Survey data provided by EDINA ©Crown Copyright and Database Right, 2011. Introduction to the city of Stirling 3 Scotland's sixth city which is the largest settlement and the administrative centre of Stirling Council Area, Stirling lies between the River Forth and the prominent 122m Settlement Information (400 feet) high crag on top of which sits Stirling Castle. Situated midway between the east and west coasts of Scotland at the lowest crossing point on the River Forth, Settlement Type: city it was for long a place of great strategic significance. To hold Stirling was to hold Scotland. Population: 32673 (2001) Tourist Rating: In 843 Kenneth Macalpine defeated the Picts near Cambuskenneth; in 1297 William Wallace defeated the National Grid: NS 795 936 English at Stirling Bridge and in June 1314 Robert the Bruce routed the English army of Edward II at Stirling Latitude: 56.12°N Bannockburn. -

Scotland: BBC Weeks 51 and 52

BBC WEEKS 51 & 52, 18 - 31 December 2010 Programme Information, Television & Radio BBC Scotland Press Office bbc.co.uk/pressoffice bbc.co.uk/iplayer THIS WEEK’S HIGHLIGHTS TELEVISION & RADIO / BBC WEEKS 51 & 52 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ MONDAY 20 DECEMBER The Crash, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland TUESDAY 21 DECEMBER River City TV HIGHLIGHT BBC One Scotland WEDNESDAY 22 DECEMBER How to Make the Perfect Cake, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland THURSDAY 23 DECEMBER Pioneers, Prog 1/5 NEW BBC Radio Scotland Scotland on Song …with Barbara Dickson and Billy Connolly, NEW BBC Radio Scotland FRIDAY 24 DECEMBER Christmas Celebration, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC One Scotland Brian Taylor’s Christmas Lunch, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland Watchnight Service, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland A Christmas of Hope, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland SATURDAY 25 DECEMBER Stark Talk Christmas Special with Fran Healy, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland On the Road with Amy MacDonald, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland Stan Laurel’s Glasgow, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland Christmas Classics, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland SUNDAY 26 DECEMBER The Pope in Scotland, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC One Scotland MONDAY 27 DECEMBER Best of Gary:Tank Commander TV HIGHLIGHT BBC One Scotland The Hebridean Trail, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Two Scotland When Standing Stones, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland Another Country Legends with Ricky Ross, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland TUESDAY 28 DECEMBER River City TV HIGHLIGHT -

The Films of Murray Grigor for IOT

Atelier e.B + PAnel Present steel uPon the swArd the Films of Murray Grigor for IOT. II 9/10 & 30 MAy 12 rose street GlAsGow FilM theAtre Glasgow G3 6rB saturday 9 May: CumbernAuld hit & The demarCo diMension (edited by rob Kennedy) sunday 10 May: steel uPon the swArd & E.P. SculPtor saturday 30 May: Mackintosh T& he FAll And rise oF Mackintosh Murray Grigor is an independent Scottish filmmaker, writer and exhibition curator. Winning international acclaim for his ongoing contribution to the arts spanning over 40 years, The Inventors of Tradition II presents a series of three double bills in partnership with Glasgow Film Theatre that celebrate his work. The selected films highlight Grigor’s interest in Scottish artistic life and bring focus to the complex connections between architecture, creative practice and cultural identity prevalent in his pioneering works. steel uPon the swArd Saturday 9 May 2015 Saturday 30 May 2015 3pm PrOGrAMMe 3pm Cinema 2 Cinema 2 Sunday 10 May 2015 CuMBernAuld HIT (edited by Rob Kennedy) MACKIntosh 3pm Sponsored by Cumbernauld Development Corporation, Cinema 2 Mackintosh (1968), Murray Grigor’s first independent and Cumbernauld Hit (1977) is an original take on ‘promotional’ seminal film won five international awards, helping to re- films produced for Scotland’s New Towns during the STeel uPOn THe Sward establish the reputation of the architect and designer, now 1970s. Footage selected from Grigor’s original feature, by From the 1970s Grigor made art and architecture a celebrated world-wide as one of the most creative figures artist Rob Kennedy, creates a new work that is at once a focus of his filmmaking. -

FOR SALE Residential Plots at RURAL SURVEYORS & CONSULTANTS Greenfoot Farm Kippen, FK8 3JH

Working with FOR SALE Residential Plots at RURAL SURVEYORS & CONSULTANTS Greenfoot Farm Kippen, FK8 3JH Offices across Scotland and Northern England www.drrural.co.uk Situation Directions The plots at Greenfoot Farm are in an ideal location for Travelling from Stirling or the M9 then leave the motorway at Residential Plots, commuting anywhere within the central belt while being J10 and take the Eastbound A84, then Raploch road to join set in stunning scenery of rural Stirlingshire. The village of Dumbarton Road/A811. Follow this road West and Greenfoot Kippen is only 2 miles away and offers a local shop and post farm is c6 miles along the road on the right hand side. The Greenfoot Farm, office, award winning butcher and a bistro/delicatessen. roundabout at Boquhan is beyond the plots. Kippen, FK8 3JH There is a local primary school at Kippen and a high school at nearby Balfron. The independent sector is well provided Description for with Fairview International School in Bridge of Allan and An opportunity to purchase three generous residential Dollar Academy, Ardvrek School and Morrison’s Academy all plots in a rural location with excellent transport links and within easy reach. Stirling is only 6 miles away and provides connectivity for home working. The plots at Greenfoot farm An excellent opportunity to acquire a more extensive shopping with a range of high street retailers have full planning permission for 4/5 bedroom detached residential plot, or all three plots, with and independent shops, a main line train station and easy houses arranged in a courtyard configuration (planning ref access to motorway links for Glasgow, Edinburgh and Perth. -

Quaint Highlanders and the Mythic North: the Representation Of

Quaint Highlanders Over the course of the nineteenth and early twentieth Scotland’s myths and the cultural formations which carried centuries, the period covered here, Scotland underwent them are complex. great social, economic and cultural change. It was a time and the Mythic North: when painting came to be accorded tremendous significance, THE MYTH OF SCOTLAND both as a record of humanity’s highest achievements and as The term myth, in this context, is taken to mean a widely The Representation of a vehicle for the expression of elemental truths. In Britain accepted interpretative traditional story embodying in the nineteenth century the middle classes assigned great fundamental beliefs. Every country has its myths. They arise Scotland in Nineteenth significance to the art they bought in increasing quantities; via judicious appropriations from the popular history of the indeed, painting became their preferred instrument for country and function as a contemporary force endorsing the promotion of their vision of a prosperous modern belief or conduct in the present. They explain and interpret Century Painting society. Art was valued insofar as it expressed their highest the world as it is found, and both assert values and extol aspirations and deepest convictions, and it was a crucial identity. Here, in addition, the concept embodies something instrument in the task of moulding a society of people of the overtones of the moral teaching of a parable. who shared these values regardless of their class, gender or John Morrison wealth. If nineteenth- and early twentieth-century painting A myth is a highly selective memory of the past used to functioned to corroborate the narratives people used to stimulate collective purpose in the present. -

RICHARD MURPHY of Its Time and of Its Place « Blog

Home page Blog Libro Lithospedia blog Pietre d'Italia english version 22 maggio 2013 News RICHARD MURPHY Of its time and of its place RICHARD MURPHY Of its time and of its place Lectio Magistralis Giovedì 30 maggio 2013 alle ore 21.00 Museo di Castelvecchio di Verona Sala Boggian Giovedì 30 maggio 2013 alle ore 21.00, presso il Museo di Castelvecchio di Verona, Sala Boggian, si terrà la Lectio Magistralis dell’architetto scozzese Richard Murphy dal titolo OF ITS TIME AND OF ITS PLACE L’evento è organizzato da Veronafiere nell’ambito delle attività culturali della 48° Marmomacc in collaborazione con il Comune di Verona, Direzione Musei d’Arte e Monumenti e l’Ordine degli Architetti, Pianificatori, Paesaggisti e Conservatori della Provincia di Verona. Appassionato conoscitore della grande tradizione architettonica inglese otto-novecentesca, Richard Murphy ha esteso il suo interesse all’opera di Carlo Scarpa. Lungo questo percorso ha costruito un legame fruttuoso con il Museo di Castelvecchio mediante una ricerca sull’opera del maestro veneziano, approfondendone pragmaticamente gli aspetti costruttivi e in particolare rilevando l’intervento nel castello scaligero. Contemporaneamente, la sua ventennale attività di architetto ha prodotto un interessante repertorio di lavori nei quali sono state indagate le relazioni tra luogo e storia, ed esplorate le potenzialità dei materiali con particolare sensibilità per l’uso della pietra. La Lectio Magistralis sarà preceduta dagli interventi di saluto del Comune di Verona, di Veronafiere, dell’Ordine degli Architetti di Verona, e introdotta da Alba Di Lieto della Direzione del Museo di Castelvecchio che parlerà del sodalizio culturale tra l’Istituzione veronese e l’architetto scozzese. -

Cowie 54 Via Bridge of Allan

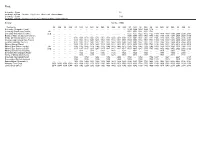

First University - Cowie 54 via Bridge of Allan - Cornton - City Centre - Braehead - Bannockburn University - Cowie 54A via Bridge of Allan - Cornton - City Centre - Whins of Milton - Bannockburn Sunday Ref.No.: 26BM Service No 54 54A 54 54A 54 54A 54 54A 54 54A 54 54A 54 54A 54 54A 54 54A 54 54 54A 54 54A 54 54A 54 University (Alexander Court) .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... 15141544161416441714 .... .... .... .... .... .... .... University (MacRobert Centre) Arr .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... 15211551162116511721 .... .... .... .... .... .... .... University (MacRobert Centre) Dep .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... 152515551625165517251800183019001930200020302100 Bridge of Allan (St Saviours Church) .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... .... 153016001630170017301805183519051935200520352105 Bridge Of Allan (at Lyon Crescent) .... .... .... .... 1031110111311201123113011331140114311501153116011631170117311806183619061936200620362106 Cornton (opp Cornton Vale Prison) .... .... .... .... 1034110411341204123413041334140414341504153416041634170417341809183919091939200920392109 Cornton (Johnston Avenue) .... .... .... .... 1037110711371207123713071337140714371507153716071637170717371812184219121942201220422112 Stirling (Murray Place) .... .... .... .... 1043111311431213124313131343141314431513154316131643171317431818184819181948201820482118 Stirling (Bus Station Lay By) Arr .... .... .... .... 1045111511451215124513151345141514451515154516151645171517451820185019201950202020502120