Geology of the Sultan Hamud Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Case Study of Rift Valley Railways Icd Service

RAILTAINER SERVICE BACKLOG: A CASE STUDY OF RIFT VALLEY RAILWAYS ICD SERVICE By Michael Odhiambo Ayimba Reg. No. D61/P/8292/03 A management research project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the award of the degree of Master of Business Administration (MBA), School of Business, University of Nairobi. 2008 University of NAIROBI Library fil0335826l 4 Declaration This research project is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other University. Name: Michael Odhiambo Ayimba Reg. No: D61/P/8292/03 Signature. Date: lib y This Management Project has been submitted for examination with my approval as University Supervisor. Name: Mr. Jacob Nyamila Muga School Of Business Signature. Date: SLl/illot i Dedication This project is dedicated first to my loving wife, Josephine Akoth, whose assistance and moral support enabled me to complete the course. Secondly it is dedicated to my late father Michael Patrick Ayimha, mother Mary Ayimha and my family members for their moral support during this period. ii Acknowledgement 1 wish to acknowledge the following without whose assistance I wouldn 7 have been able to complete this document. Firstly, I would like to thank my supervisor, Mr. Jacob M. Nyamila for his patience, guidance and the indispensable assistance that he gave during the inception and actual writing of the pro ject. Secondly, I would like to thank the Kenya Railways Management for sponsoring me for the MBA course. Special thanks to Rift Valley Railways Management for allowing me to conduct the research. Special thanks to my colleagues .James Siele, Dorothy Muluka and Tom Of ijo for assisting me with literature material and administration of the questionnaires. -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank Public Disclosure Authorized Report No. 26444-KE Public Disclosure Authorized KENYA TRANSPORT SECTOR MEMORANDUM Public Disclosure Authorized VOLUME III Public Disclosure Authorized KENYA TRANSPORT SECTOR MEMORANDUM Volume 3 ANNEXES ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Pages ANNEX 1: Kenya Main Road Network 1. Introduction 1 2. Survey Background 1 3. Road Service Standards: Main Paved Network 2 4. Road Conditions: Main Paved Network 4 5. Traffic Flows: Main Paved Network 5 6. Engineering Assessment: Main Paved Network 5 7. On-Going Engineering Activities 8 8. The Unpaved Road Network 9 9. Road Categories for Maintenance and Intervention Planning 11 10. District Perspectives 11 Annex A: Vehicle Speeds 15 Annex B: Kenya Traffic 17 ANNEX 2: Port of Mombasa: Cargo Clearance 1. Export Clearance 18 2. Import Clearance 19 3. Transit Procedures 23 4. Informal Payments and Streamlining Clearance 23 ANNEX 3" Civil Aviation 1. Kenya Airways: Key Operating Statistics 25 2. Finances 26 3. International Scheduled Services: Foreign Carriers 27 4. Principal Airports: Physical Characteristics 28 5. Minor Airports 29 6. Air Transport: Commercial Aircrafts 30 This Transport Sector Memorandum was prepared on the basis of missions in November, 2001 and mid- 2002, by Mr. Simon Thomas (Senior Transport Economist) in collaboration with Mr. Josphat Sasia (Operations Officer, AFTTR), Mr. David Rudge (Senior Road Engineer, AFTTR), Mr. Yash Pal Kedia (Principal Railways Engineer, AFTTR), Mr. John King (Aviation Consultant) and Mr. Paul Thompson (Port Consultant). The Road Sector Review was undertaken with the active participation and support of the DFID, EU, KfW and SIDA. The views and recommendations contained in the Transport Sector Memorandum are those of the review team and are not necessarily endorsed by the Management of the World Bank ANNEX 1 KENYA MAIN ROAD NETWORK Review of Present Status and Conditions 1. -

The Role of Constituency Development Fund in Provision of Secondary School Education in Kenya

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & TECHNOLOGY RESEARCH VOLUME 3, ISSUE 8, AUGUST 2014 ISSN 2277-8616 The Role Of Constituency Development Fund In Provision Of Secondary School Education In Kenya Ng‟alu Mutie Michael, Bomett J. Emily Ph.D ABSTRACT: The purpose of this study was to investigate the role of the Constituency Development Fund (CDF) in the provision of secondary school education in Kilome constituency. The objectives of the study were; To assess the challenges faced by secondary schools in accessing CDF funds in Kilome constituency, to establish the role of CDF in provision of secondary school education in Kilome constituency, to determine the effect of CDF on enrolment in secondary schools in Kilome constituency.The study employed a survey design. The target population was 35headteachers from 35 secondary schools in Kilome constituency. It employed stratified sampling to obtain strata on the basis of the administrative divisions: Kilome (14 schools) and Kasikeu (21 schools). The researcher selected 6 schools from Kilome division and 8 schools from Kasikeu division making a total of 14 public secondary schools. The study randomly sampled 140 form three students, ten students from each school. The instruments of data collection were questionnaires and interview schedules. Reliability was ensured through the test retest method. Descriptive methods were employed in data analysis where frequencies and proportions were used in presenting the respondents‟ perception of issues raised in the questionnaires so as to answer the research questions. The study found out that success of CDF was being undermined by inadequate amount awarded, discrimination and mismanagement of funds and hence the amount awarded should be increased and cases of discrimination and corruption should be curbed.It is hoped that the findings of this study will contribute to the understanding of the role of the CDF in addressing the issue of provision of secondary school education in constituency. -

Kyanite in Kenya—The Mubai and the Musuriamboi Kyanite-Quartz Schists

FOREWORD Massive easily workable kyanite was first discovered in Kenya in 1942 and pro- duction started in 1944. Six years later Kenya was the world’s chief producer of kyanite. Since then there has been a fall off in production as the more accessible rich ore was worked out, but as a process for the extraction of kyanite from less rich material has been evolved, it may be expected that the production will once again rise. The kyanite now extracted is calcined and converted to mullite before export. Dr. Temperley in this, the first memoir published by the Geological Survey of Kenya, gives a full account of the history of development of the industry and of the kyanite deposits that are either worked or known in various parts of Kenya. He also gives an account of kyanite deposits throughout the world, providing a classification of the various types of deposits, and attempts to solve the problems of the genesis of their rocks. To assist prospectors early chapters of the memoir deal with the properties of kyanite and allied minerals, and the specifications for saleable material. The work entailed in the preparation of the memoir was made possible by means of a grant from the Colonial Development and Welfare Vote. Mr. A. L. Stewart, Metallurgist in the Mines and Geological Department, contri- buted sections on the laboratory investigation of newly discovered deposits. Other colleagues in the department assisted by discussion and in the search for literature. Nairobi, WILLIAM PULFREY, 30th July, 1952. Chief Geologist. CONTENTS PAGE I. Introduction 1 II. Uses and properties of kyanite . -

![Ahmed Mohammed Ibrahim V Wiper Democratic Movement Party [2017] Eklr](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2007/ahmed-mohammed-ibrahim-v-wiper-democratic-movement-party-2017-eklr-3352007.webp)

Ahmed Mohammed Ibrahim V Wiper Democratic Movement Party [2017] Eklr

Ahmed Mohammed Ibrahim v Wiper Democratic Movement Party [2017] eKLR REPUBLIC OF KENYA IN THE POLITICAL PARTIES DISPUTES TRIBUNAL AT NAIROBI COMPLAINT NO. 521 OF 2017 AHMED MOHAMMED IBRAHIM………………...…COMPLAINANT VERSUS WIPER DEMOCRATIC MOVEMENT PARTY….…….RESPONDENT JUDGMENT Introduction 1. The Claimant identifies as an ethnic Somali, a minority community within Makueni County. He is registered to vote, as he has done over the years, at Sultan Hamud Primary School in Kilome Constituency. He is a registered party member of the Respondent. His application for nomination on the list of marginalized groups was approved and accepted. His name was as a matter of fact included in the initial list accruing a legitimate expectation of nomination. 2. He avers that Makueni County is ethnically diverse and that this diversity ought to reflect in any legitimate party list. As such he asserts that the Respondent’s party list for nomination to Makueni County Assembly is unlawful because it discriminates against minorities within Makueni County. In fact, even those stated to represent so called marginalized clans are still drawn from the dominant Akamba ethnic community. He therefore seeks an amendment of the list of marginalized groups to include his name. 3. There is an affidavit of service on record. The claim is undefended. PPDT Complaint No 521 of 2017 - Judgment Page 1 of 5 Ahmed Mohammed Ibrahim v Wiper Democratic Movement Party [2017] eKLR Analysis 4. The Constitution of Kenya, 2010 bespeaks the pride of Kenyans in their ethnic, cultural and religious diversities. It similarly reiterates the common aspiration for a government based on the essential values of human rights, equality, freedom, democracy, social justice and the rule of law. -

SGR EAS Impact Report

ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT STUDY REPORT FOR THE PROPOSED MOMBASA-NAIROBI STANDARD GAUGE RAILWAY PROJECT ENVIRONMENTAL CONSULTANTS CONTRACTOR Africa Waste and Environment Management Centre (AWEMAC) China Road and Bridge Corporation Limuru Road, Muthaiga Mini Market CRBC Complex, Left wing 3rd Floor P.O. Box 39037, NAIROBI P.O. Box 63891-00619 Plot 330/265, Hatheru Road-Lavington Muthaiga- NAIROBI. Tel: 020-3877955/3870956 Tel: - 020-2012408/0704333166 Fax: 020-3870334 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Website: www.awemac.co.ke Website http://www.crbc.com FIRM NEMA Reg. No. 0527 PROPONENT Vision 2030 Government Flangship Project KENYA RAILWAYS CORPORATION P. O. Box 30121 - 00100, Off Haile Selassie Avenue, Nairobi, Kenya | Tel: 254-20-2210111 / 2215211 / 2210200 | Fax: 254-20-340049 / 221456 | Email: [email protected] OCTOBER 2012 i ESIA Study Report for the Mombasa – Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway Project AWEMAC©2012 SUBMISSION OF DOCUMENTATION I, Prof. Jacob K. Kibwage on behalf of Africa Waste and Environment Management Centre (AWEMAC) submit the following Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Study Report for the Proposed Mombasa – Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway Project. To my knowledge, all information contained in this report is accurate and a truthful representation of all findings as relating to the proposed project. Signed at NAIROBI on this ………. day of October 2012. Signature: …………………………………………………………. Designation: Lead Environmental Consultant SUBMISSION OF DOCUMENTATION I, .…………………………………………............................................................, on behalf of China Road and Bridge Corporation (Contractor) and Kenya Railways Corporation(Proponent) submit this Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Study Report for the Proposed Mombasa – Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway Project . To my knowledge, all information contained in this report is accurate and a truthful representation of all findings as relating to the proposed project. -

Hansard Report Is for Information Purposes Only

March 30, 2021 NATIONAL ASSEMBLY DEBATES 1 PARLIAMENT OF KENYA THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY THE HANSARD Tuesday, 30th March 2021 The House met at 2.30 p.m. [The Speaker (Hon. Justin Muturi) in the Chair] PRAYERS MESSAGE Hon. Speaker: Hon. Members, it will be communicated later. PETITIONS Hon. Speaker: The Member for Malava, Hon. Malulu Injendi. COMPENSATION FOR FAMILY OF THE LATE NANCY KHARWALI Hon. Moses Injendi (Malava, JP): Thank you, Hon. Speaker. This is Public Petition (No.013 of 2021) regarding compensation for the family of the late Nancy Kharwali. I, the undersigned, on behalf of the family of the late Nancy Sarah Kharwali draw the attention of the House to the following: THAT, Ms. Nancy Sarah Kharwali was shot and killed by police officers on 22ndApril 2012 (Death Certificate Number 0261207705) while washing clothes on the balcony of her residence on the 5thfloor of Elino House in Dandora Phase 4, Nairobi during an attempt by the police to control a riotous mob nearby; THAT, following the incident, the niece to Ms. Kharwali, who also serves as the legal administrator of her estate namely John Musotsi Wangusi, filed Civil Case No. 2025 of 2013, seeking compensation for the wrongful killing; THAT, on 16thMay 2019, the Milimani Commercial Court ruled that the police officers were culpable of gross negligence and awarded the family of the late Ms. Kharwali compensation totaling Kshs 3,325,200 and later issued decrees on 17thJuly 2019, with added interest that increased the total award to Kshs. 3,618,857.20; THAT, to-date, the Attorney General has failed to honour and effect this payment despite numerous reminders by the deceased’s family; THAT, the late Ms. -

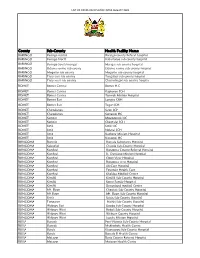

List of Covid-Vaccination Sites August 2021

LIST OF COVID-VACCINATION SITES AUGUST 2021 County Sub-County Health Facility Name BARINGO Baringo central Baringo county Referat hospital BARINGO Baringo North Kabartonjo sub county hospital BARINGO Baringo South/marigat Marigat sub county hospital BARINGO Eldama ravine sub county Eldama ravine sub county hospital BARINGO Mogotio sub county Mogotio sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty east sub county Tangulbei sub county hospital BARINGO Tiaty west sub county Chemolingot sub county hospital BOMET Bomet Central Bomet H.C BOMET Bomet Central Kapkoros SCH BOMET Bomet Central Tenwek Mission Hospital BOMET Bomet East Longisa CRH BOMET Bomet East Tegat SCH BOMET Chepalungu Sigor SCH BOMET Chepalungu Siongiroi HC BOMET Konoin Mogogosiek HC BOMET Konoin Cheptalal SCH BOMET Sotik Sotik HC BOMET Sotik Ndanai SCH BOMET Sotik Kaplong Mission Hospital BOMET Sotik Kipsonoi HC BUNGOMA Bumula Bumula Subcounty Hospital BUNGOMA Kabuchai Chwele Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma County Referral Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi St. Damiano Mission Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Elgon View Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Bungoma west Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi LifeCare Hospital BUNGOMA Kanduyi Fountain Health Care BUNGOMA Kanduyi Khalaba Medical Centre BUNGOMA Kimilili Kimilili Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Korry Family Hospital BUNGOMA Kimilili Dreamland medical Centre BUNGOMA Mt. Elgon Cheptais Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Mt.Elgon Mt. Elgon Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Sirisia Sirisia Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Tongaren Naitiri Sub-County Hospital BUNGOMA Webuye -

TRANSPORT-POLICY-DOCUMENT-.Pdf

TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD................................................................................................................................. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .......................................................................................................... 3 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ..................................................................................... 4 1.1 Introduction .................................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Rationale for the Policy ...................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Guiding Principles .............................................................................................................. 7 1.4 Policy Statement .................................................................................................................. 8 1.5 Scope of the Policy .............................................................................................................. 8 1.6 Policy Development Process ............................................................................................... 8 CHAPTER 2: SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS .............................................................................. 9 2.1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 9 2.2 Legal and Institutional Framework........................................................................... -

Chinese FDI a Study of the Impact of Chinese Infrastructure Investments in Kenya, Africa

Chinese FDI A study of the impact of Chinese infrastructure investments in Kenya, Africa xiaotian sun 2015-5-5 Acknowledgement Foremost, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my advisor Prof. Elliot Sclar for the continuous support of my master study and research, for his patience, motivation, enthusiasm, and immense knowledge. His guidance helped me in all the time of research and writing of this thesis. I could not have imagined having a better advisor and mentor for my study. Besides my advisor, I would like to thank my reader Prof. Xin Li for her encouragement, insightful comments, and hard questions. I would like to thank my family: my parents Ziyu Sun and Yanjun Cai, for giving birth to me at the first place and supporting me spiritually throughout my life. Abstract Over the last century, Chinese Foreign Direct Investments have made great impacts on African countries. Large amounts of FDI from China has flooded into African infrastructure investments, targeting key sectors such as telecommunications, transportation, power plants, and port refurbishments. No doubt China treats itself as an equal and a generous partner of African countries, yet not an uncontroversial one especially from the perspective of foreign observers. There have been many critical voices on China-Africa relations over the years. In order to test the validity of the critiques as well as the praises, two infrastructure construction projects were chosen as case studies in this thesis. They are the Standard Gauge Railroad and A109 national road. Both contracts were signed between the Kenyan government and a Chinese state-owned company, Chinese Road and Bridge Cooperation (CRBC). -

IEBC Report on Constituency and Ward Boundaries

REPUBLIC OF KENYA THE INDEPENDENT ELECTORAL AND BOUNDARIES COMMISSION PRELIMINARY REPORT ON THE FIRST REVIEW RELATING TO THE DELIMITATION OF BOUNDARIES OF CONSTITUENCIES AND WARDS 9TH JANUARY 2012 1 CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE ............................................................................................................................................... 8 BACKGROUND INFORMATION ...................................................................................................................... 8 1.1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 8 1.2. System and Criteria in Delimitation .............................................................................................. 9 1.3. Objective ....................................................................................................................................... 9 1.4. Procedure ...................................................................................................................................... 9 1.5. Boundary Delimitation In Kenya: Historical Perspective ............................................................. 11 1.5.1 An Overview of Boundary Delimitation in Kenya ........................................................................... 11 CHAPTER TWO ............................................................................................................................................ 14 LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR THE DELIMITATION OF BOUNDARIES -

Mombasa Road Rehabilitation Project

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized ReportNo. P-6503-KE MEMORANDUM AND RECOMMENDATION OF THE PRESIDENT OF THE INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION TO THE Public Disclosure Authorized EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS ON A PROPOSED CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 34.0 MILLION TO THE REPUBLIC OF KENYA FOR A Public Disclosure Authorized NAIROBI-MOMBASA ROAD REHABILITATION PROJECT NOVEMBER 8, 1995 Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency unit = Kenya Shilling (K Sh) US$ 1.00 = K Sh 55.00 (As of October 1995) K Sh 1.00 = USSO.02 K Sh 20.00 = K£ 1.0 WEIGHTS AND MEASURES Metric System GLOSSARY OF ABBREVIATIONS EU European Union GOK Governnmentof Kenya ICB International Competitive Bidding IDA International Development Association LCB Local Competitive Bidding PPF Project Preparation Facility SDR Special Drawing Rights GOVERNMENT FISCAL YEAR Julv I - June 30 FOR OFFICIALUSE ONLY KENYA NAIROBI - MOMBASA ROAD REHABILITATION PROJECT CREDIT AND PROJPFCTSU MMAIRY Borrower: The Republic of Kenya Implementing Agency: Ministry of Public Works and Housing Beneficiary: Not applicable Poverty: Not applicable Amount: SDR 34.0 millioni (USS50.0 millioni equivalent) Terms: Standard IDA terms with 40 year-s maturity Financing Plan: Schedule A Net Present Value: US$138 millioni at 12% discount rate. ERR 43.9%Z,(NItito Andei - Bachuimia Gate Section. 43 % of project cost) The Sultan Hamud - Mtito Andei Sectioniis expected to gyenerate similar economic benefits, see Para.