Education Kit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Driving Holidays in the Northern Territory the Northern Territory Is the Ultimate Drive Holiday Destination

Driving holidays in the Northern Territory The Northern Territory is the ultimate drive holiday destination A driving holiday is one of the best ways to see the Northern Territory. Whether you are a keen adventurer longing for open road or you just want to take your time and tick off some of those bucket list items – the NT has something for everyone. Top things to include on a drive holiday to the NT Discover rich Aboriginal cultural experiences Try tantalizing local produce Contents and bush tucker infused cuisine Swim in outback waterholes and explore incredible waterfalls Short Drives (2 - 5 days) Check out one of the many quirky NT events A Waterfall hopping around Litchfield National Park 6 Follow one of the unique B Kakadu National Park Explorer 8 art trails in the NT C Visit Katherine and Nitmiluk National Park 10 Immerse in the extensive military D Alice Springs Explorer 12 history of the NT E Uluru and Kings Canyon Highlights 14 F Uluru and Kings Canyon – Red Centre Way 16 Long Drives (6+ days) G Victoria River region – Savannah Way 20 H Kakadu and Katherine – Nature’s Way 22 I Katherine and Arnhem – Arnhem Way 24 J Alice Springs, Tennant Creek and Katherine regions – Binns Track 26 K Alice Springs to Darwin – Explorers Way 28 Parks and reserves facilities and activities 32 Festivals and Events 2020 36 2 Sealed road Garig Gunak Barlu Unsealed road National Park 4WD road (Permit required) Tiwi Islands ARAFURA SEA Melville Island Bathurst VAN DIEMEN Cobourg Island Peninsula GULF Maningrida BEAGLE GULF Djukbinj National Park Milingimbi -

Hydrogeological Review of the Musgrave Province, South Australia

Hydrogeological review of the Musgrave Province, South Australia Sunil Varma Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series No. 12/8 www.goyderinstitute.org Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series ISSN: 1839-2725 The Goyder Institute for Water Research is a partnership between the South Australian Government through the Department for Environment, Water and Natural Resources, CSIRO, Flinders University, the University of Adelaide and the University of South Australia. The Institute will enhance the South Australian Government’s capacity to develop and deliver science-based policy solutions in water management. It brings together the best scientists and researchers across Australia to provide expert and independent scientific advice to inform good government water policy and identify future threats and opportunities to water security. Enquires should be addressed to: Goyder Institute for Water Research Level 1, Torrens Building 220 Victoria Square, Adelaide, SA, 5000 tel: 08-8303 8952 e-mail: [email protected] Citation Varma, S., 2012, Hydrogeological review of the Musgrave Province, South Australia, Goyder Institute for Water Research Technical Report Series No. 12/8. Copyright © 2012 CSIRO To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of CSIRO. Disclaimer The Participants advise that the information contained in this publication comprises -

Australian Curriculum: Science Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

Australian Curriculum: Science Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures cross-curriculum priority Content elaborations and teacher background information for Years 7-10 JULY 2019 2 Content elaborations and teacher background information for Years 7-10 Australian Curriculum: Science Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures cross-curriculum priority Table of contents Introduction 4 Teacher background information 24 for Years 7 to 10 Background 5 Year 7 teacher background information 26 Process for developing the elaborations 6 Year 8 teacher background information 86 How the elaborations strengthen 7 the Australian Curriculum: Science Year 9 teacher background information 121 The Australian Curriculum: Science 9 Year 10 teacher background information 166 content elaborations linked to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures cross-curriculum priority Foundation 10 Year 1 11 Year 2 12 Year 3 13 Year 4 14 Year 5 15 Year 6 16 Year 7 17 Year 8 19 Year 9 20 Year 10 22 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures cross-curriculum priority 3 Introduction This document showcases the 95 new content elaborations for the Australian Curriculum: Science (Foundation to Year 10) that address the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures cross-curriculum priority. It also provides the accompanying teacher background information for each of the elaborations from Years 7 -10 to support secondary teachers in planning and teaching the science curriculum. The Australian Curriculum has a three-dimensional structure encompassing disciplinary knowledge, skills and understandings; general capabilities; and cross-curriculum priorities. It is designed to meet the needs of students by delivering a relevant, contemporary and engaging curriculum that builds on the educational goals of the Melbourne Declaration. -

Coober Pedy, South Australia

The etymology of Coober Pedy, South Australia Petter Naessan The aim of this paper is to outline and assess the diverging etymologies of ‘Coober Pedy’ in northern South Australia, in the search for original and post-contact local Indigenous significance associated with the name and the region. At the interface of contemporary Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara opinion (mainly in the Coober Pedy region, where I have conducted fieldwork since 1999) and other sources, an interesting picture emerges: in the current use by Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara people as well as non-Indigenous people in Coober Pedy, the name ‘Coober Pedy’ – as ‘white man’s hole (in the ground)’ – does not seem to reflect or point toward a pre-contact Indigenous presence. Coober Pedy is an opal mining and tourist town with a total population of about 3500, situated near the Stuart Highway, about 850 kilometres north of Adelaide, South Australia. Coober Pedy is close to the Stuart Range, lies within the Arckaringa Basin and is near the border of the Great Victoria Desert. Low spinifex grasslands amounts for most of the sparse vegetation. The Coober Pedy and Oodnadatta region is characterised by dwarf shrubland and tussock grassland. Further north and northwest, low open shrub savanna and open shrub woodland dominates.1 Coober Pedy and surrounding regions are arid and exhibit very unpredictable rainfall. Much of the economic activity in the region (as well as the initial settlement of Euro-Australian invaders) is directly related to the geology, namely quite large deposits of opal. The area was only settled by non-Indigenous people after 1915 when opal was uncovered but traditionally the Indigenous population was western Arabana (Midlaliri). -

Supplementary Budget Estimates 18-22 November 2013

Financial Management Support Services Scoping Study Amata and Mimili September 2011 Financial Management Support Services Scoping Study for Amata and Mimili. Contents 1. Acknowledgements 3 2. Introduction 4 3. The Project 5 3.1 Limitations 6 4. Executive Summary 8 4.1 Recommendations 8 4.2 Recommendations to address serious risks to the 9 effectiveness of Financial Wellbeing Service in Amata and Mimili 5. The Communities 10 5.1 Amata 10 5.2 Mimili 11 6. Financial Wellbeing 13 6.1 Financial Wellbeing for Anangu 14 7. Financial literacy 19 8. Consultations and Participation 21 8.1 Highlighted observations 22 8.2 Common Findings 25 9. The Gap Analysis 27 9.1 Existing Financial Support Services 27 9.2 Current Services 28 9.3 Lessons Learned from Current service Providers 30 10. Considered models 32 10.1Proposed Service Delivery Model - Primary objectives 32 and outcomes of the service 10.2 Core Elements 33 10.2.1 Linkages with other providers 33 10.2.2Provider Capacity 35 10.2.3 Infrastructure Requirements 35 10.2.4 Staffing and Capacity 35 10.2.5 Locations 37 10.2.6 Accommodation 38 10.2.7 Service Delivery 38 BBM 2010/11:14 1 Financial Management Support Services Scoping Study for Amata and Mimili. Contents, continued 11. Measures of success 39 12. Communication Flows 40 13. Risks 41 14. Financial Education 46 Figures Figure 1 Map of APY Communities 13 Figure 2 Elements of Wellbeing 15 Figure 3 Amata Financial Wellbeing Centre – Staff 37 Figure 4 Mimili Financial Wellbeing Centre – Staff 37 Figure 5 Communication Flows 40 Appendices Appendix 1 An evaluation of a programme of financial education 48 provided by the Greater Easterhouse Money Advice Project Appendix 2 Family Income Management (FIM) – Cape York 50 Appendix 3 Amata and Mimili Profiles 52 Appendix 4 Substance Abuse Intelligence Desks 57 Appendix 5 Sample Job Description — Financial Counselor 58 Sample Job Description —Money management Worker 59 BBM 2010/11:14 2 Financial Management Support Services Scoping Study for Amata and Mimili. -

GREAT ARTESIAN BASIN Responsibility to Any Person Using the Information Or Advice Contained Herein

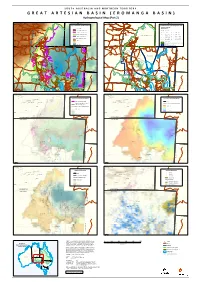

S O U T H A U S T R A L I A A N D N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y G R E A T A R T E S I A N B A S I N ( E RNturiyNaturiyaO M A N G A B A S I N ) Pmara JutPumntaara Jutunta YuenduYmuuendumuYuelamu " " Y"uelamu Hydrogeological Map (Part " 2) Nyirri"pi " " Papunya Papunya ! Mount Liebig " Mount Liebig " " " Haasts Bluff Haasts Bluff ! " Ground Elevation & Aquifer Conditions " Groundwater Salinity & Management Zones ! ! !! GAB Wells and Springs Amoonguna ! Amoonguna " GAB Spring " ! ! ! Salinity (μ S/cm) Hermannsburg Hermannsburg ! " " ! Areyonga GAB Spring Exclusion Zone Areyonga ! Well D Spring " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " " " " Extent of Saturated Aquifer ! D 1 - 500 ! D 5001 - 7000 Extent of Confined Aquifer ! D 501 - 1000 ! D 7001 - 10000 Titjikala Titjikala " " NT GAB Management Zone ! D ! Extent of Artesian Water 1001 - 1500 D 10001 - 25000 ! D ! Land Surface Elevation (m AHD) 1501 - 2000 D 25001 - 50000 Imanpa Imanpa ! " " ! ! D 2001 - 3000 ! ! 50001 - 100000 High : 1515 ! Mutitjulu Mutitjulu ! ! D " " ! 3001 - 5000 ! ! ! Finke Finke ! ! ! " !"!!! ! Northern Territory GAB Water Control District ! ! ! Low : -15 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! FNWAP Management Zone NORTHERN TERRITORY Birdsville NORTHERN TERRITORY ! ! ! Birdsville " ! ! ! " ! ! SOUTH AUSTRALIA SOUTH AUSTRALIA ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!!!!! !!!! D !! D !!! DD ! DD ! !D ! ! DD !! D !! !D !! D !! D ! D ! D ! D ! D ! !! D ! D ! D ! D ! DDDD ! Western D !! ! ! ! ! Recharge Zone ! ! ! ! ! ! D D ! ! ! ! ! ! N N ! ! A A ! L L ! ! ! ! S S ! ! N N ! ! Western Zone E -

Centring Anangu Voices

Report NR005 2017 Centring Anangu Voices A research project exploring how Nyangatjatjara College might better strengthen Anangu aspirations through education Sam Osborne John Guenther Lorraine King Karina Lester Sandra Ken Rose Lester Cen Centring Anangu Voices A research project exploring how Nyangatjatjara College might better strengthen Anangu aspirations through education. December 2017 Research conducted by Ninti One Ltd in conjunction with Nyangatjatjara College Dr Sam Osborne, Dr John Guenther, Lorraine King, Karina Lester, Sandra Ken, Rose Lester 1 Executive Summary Since 2011, Nyangatjatjara College has conducted a series of student and community interviews aimed at providing feedback to the school regarding student experiences and their future aspirations. These narratives have developed significantly over the last seven years and this study, a broader research piece, highlights a shift from expressions of social and economic uncertainty to narratives that are more explicit in articulating clear directions for the future. These include: • A strong expectation that education should engage young people in training and work experiences as a pathway to employment in the community • Strong and consistent articulation of the importance of intergenerational engagement to 1. Ground young people in their stories, identity, language and culture 2. Encourage young people to remain focussed on positive and productive pathways through mentoring 3. Prepare young people for work in fields such as ranger work and cultural tourism • Utilise a three community approach to semi-residential boarding using the Yulara facilities to provide access to expert instruction through intensive delivery models • Metropolitan boarding programs have realised patchy outcomes for students and families. The benefits of these experiences need to be built on through realistic planning for students who inevitably return (between 3 weeks and 18 months from commencement). -

Native Title Groups from Across the State Meet

Aboriginal Way www.nativetitlesa.org Issue 69, Summer 2018 A publication of South Australian Native Title Services Above: Dean Ah Chee at a co-managed cultural burn at Witjira NP. Read full article on page 6. Native title groups from across the state meet There are a range of support services Nadja Mack, Advisor at the Land Branch “This is particularly important because PBC representatives attending heard and funding options available to of the Department and Prime Minister the native title landscape is changing… from a range of organisations that native title holder groups to help and Cabinet (PM&C) told representatives we now have more land subject to offer support and advocacy for their them on their journey to become from PBCs present that a 2016 determination than claims, so about organisations, including SA Native independent and sustainable consultation had led her department to 350 determinations and 240 claims, Title Services (SANTS), the Indigenous organisations that can contribute currently in Australia. focus on giving PBCs better access to Land Corporation (ILC), Department significantly to their communities. information, training and expertise; on “We have 180 PBCs Australia wide, in of Environment Water and Natural That was the message to a forum of increasing transparency and minimising South Australia 15 and soon 16, there’s Resources (DEWNR), AIATSIS, Indigenous South Australian Prescribed Bodies disputes within PBCs; on providing an estimate that by 2025 there will be Business Australia (IBA), Office of the Corporate (PBCs) held in Adelaide focussed support by native title service about 270 – 290 PBCs Australia wide” Registrar of Indigenous Corporations recently. -

Appendix a (PDF 85KB)

A Appendix A: Committee visits to remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait communities As part of the Committee’s inquiry into remote Indigenous community stores the Committee visited seventeen communities, all of which had a distinctive culture, history and identity. The Committee began its community visits on 30 March 2009 travelling to the Torres Strait and the Cape York Peninsula in Queensland over four days. In late April the Committee visited communities in Central Australia over a three day period. Final consultations were held in Broome, Darwin and various remote regions in the Northern Territory including North West Arnhem Land. These visits took place in July over a five day period. At each location the Committee held a public meeting followed by an open forum. These meetings demonstrated to the Committee the importance of the store in remote community life. The Committee appreciated the generous hospitality and evidence provided to the Committee by traditional owners and elders, clans and families in all the remote Aboriginal and Torres Strait communities visited during the inquiry. The Committee would also like to thank everyone who assisted with the administrative organisation of the Committee’s community visits including ICC managers, Torres Strait Councils, Government Business Managers and many others within the communities. A brief synopsis of each community visit is set out below.1 1 Where population figures are given, these are taken from a range of sources including 2006 Census data and Grants Commission figures. 158 EVERYBODY’S BUSINESS Torres Strait Islands The Torres Strait Islands (TSI), traditionally called Zenadth Kes, comprise 274 small islands in an area of 48 000 square kilometres (kms), from the tip of Cape York north to Papua New Guinea and Indonesia. -

CENTRAL LAND COUNCIL Submission to the Independent

CENTRAL LAND COUNCIL Submission to the Independent Reviewer Independent Review of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (Cth) 1999 16 April 2020 HEAD OFFICE 27 Stuart Hwy, Alice Springs POST PO Box 3321 Alice Springs NT 0871 1 PHONE (08) 8951 6211 FAX (08) 8953 4343 WEB www.clc.org.au ABN 71979 619 0393 ALPARRA (08) 8956 9955 HARTS RANGE (08) 8956 9555 KALKARINGI (08) 8975 0885 MUTITJULU (08) 5956 2119 PAPUNYA (08) 8956 8658 TENNANT CREEK (08) 8962 2343 YUENDUMU (08) 8956 4118 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. SUMMARY OF RECOMMENDATIONS ....................................................................... 3 2. ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .......................................................................... 4 3. OVERVIEW ...................................................................................................................... 5 4. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 5 5. MODERNISING CONSULTATION AND INPUT ......................................................... 7 5.1. Consultation processes ................................................................................................... 8 5.2. Consultation timing ........................................................................................................ 9 5.3. Permits to take or impact listed threatened species or communities ........................... 10 6. CULTURAL HERITAGE AND SITE PROTECTION .................................................. 11 7. BILATERAL -

Diesel and Damper: Changes in Seed Use and Mobility Patterns Following Contact Amongst the Martu of Western Australia ⇑ David W

Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 39 (2015) 51–62 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Anthropological Archaeology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jaa Diesel and damper: Changes in seed use and mobility patterns following contact amongst the Martu of Western Australia ⇑ David W. Zeanah a, , Brian F. Codding b, Douglas W. Bird c, Rebecca Bliege Bird c, Peter M. Veth d a Department of Anthropology, California State University, Sacramento, 6000 J Street, Sacramento, CA 95819, United States b Department of Anthropology, University of Utah, 270 S. 1400 East, Rm 102, Salt Lake City, UT 84112, United States c Department of Anthropology, Stanford University, 450 Serra Mall, Bldg. 50, Stanford, CA 94305, United States d School of Social Sciences, The University of Western Australia (M257), 35 Stirling Highway, Crawley, WA 6009, Australia article info abstract Article history: Seed-reliant, hunting and gathering economies persisted in arid Australia until the mid-twentieth cen- Received 5 June 2014 tury when Aboriginal foragers dropped seeds from their diets. Explanations posed to account for this Revision received 23 February 2015 ‘‘de-intensification’’ of seed use mix functional rationales (such as dietary breadth contraction as pre- Available online 25 March 2015 dicted by the prey choice model) with proximate causes (substitution with milled flour). Martu people of the Western Desert used small seeds until relatively recently (ca. 1990) with a subsequent shift to a Keywords: less ‘‘intensive’’ foraging economy. Here we examine contemporary Martu foraging practices to evaluate Broad spectrum revolution different explanations for the dietary shift and find evidence that it resulted from a more subtle interac- Foraging theory tion of technology, travel, burning practices, and handling costs than captured solely by the prey choice Marginal Value Theorem Seed use model. -

Introduction & Recommendations

Separate Attachment COM 20A Ordinary Meeting of Council 26 April 2016 MOUNT ALEXANDER SHIRE THEMATIC HERITAGE STUDY ARCHITECTS CONSERVATION Introduction & CONSULTANTS Recommendations TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction 1.1 Background 1 1.2 Brief 2 1.3 Study Area 2 1.4 Earlier Reports 3 1.5 Study Team 3 1.5 Acknowledgements 3 2 Methodology 2.1 General 4 2.2 Survey Work 4 2.3 Research 4 2.4 Consultation 5 3 The Themes 3.1 The Framework 6 3.2 Overview of the Themes 6 4 Recommendations 4.1 Introduction 8 4.2 Existing Schedule to the Heritage Overlay 8 4.3 Further Review Work 9 Mount Alexander Shire Thematic Heritage Study Introduction & Recommendations Volume 1 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background This Thematic Heritage Study has been prepared for the Shire of Mount Alexander by RBA Architects and Conservation Consultants. It consists of two sections: Volume 1 – Introduction & Recommendations. This volume outlines the process by which the thematic history was prepared as well as recommending some areas for further investigation and places of potential significance. Volume 2 – A Thematic History of the Shire according to nine themes and concluding with a Statement of Significance. The need for the preparation of an all-encompassing, Shire-wide thematic history had been identified as a key priority in the local Heritage Strategy 2012-2016.1 A thematic history has previously been prepared for sections of Mount Alexander Shire, within the heritage studies of the former shires of Metcalfe and Newstead. In addition, although many places are protected by heritage overlays further assessment was needed according to the Heritage Strategy as follows: Protecting & Managing There are over 1000 places in the Schedule to the Heritage Overlay however these are unevenly spread across the Shire.