Werther Vs. Werther: from Print to the Operatic Stage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10-26-2019 Manon Mat.Indd

JULES MASSENET manon conductor Opera in five acts Maurizio Benini Libretto by Henri Meilhac and Philippe production Laurent Pelly Gille, based on the novel L’Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut set designer Chantal Thomas by Abbé Antoine-François Prévost costume designer Saturday, October 26, 2019 Laurent Pelly 1:00–5:05PM lighting designer Joël Adam Last time this season choreographer Lionel Hoche revival stage director The production of Manon was Christian Räth made possible by a generous gift from The Sybil B. Harrington Endowment Fund general manager Peter Gelb Manon is a co-production of the Metropolitan Opera; jeanette lerman-neubauer Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Teatro music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin alla Scala, Milan; and Théâtre du Capitole de Toulouse 2019–20 SEASON The 279th Metropolitan Opera performance of JULES MASSENET’S manon conductor Maurizio Benini in order of vocal appearance guillot de morfontaine manon lescaut Carlo Bosi Lisette Oropesa* de brétigny chevalier des grieux Brett Polegato Michael Fabiano pousset te a maid Jacqueline Echols Edyta Kulczak javot te comte des grieux Laura Krumm Kwangchul Youn roset te Maya Lahyani an innkeeper Paul Corona lescaut Artur Ruciński guards Mario Bahg** Jeongcheol Cha Saturday, October 26, 2019, 1:00–5:05PM This afternoon’s performance is being transmitted live in high definition to movie theaters worldwide. The Met: Live in HD series is made possible by a generous grant from its founding sponsor, The Neubauer Family Foundation. Digital support of The Met: Live in HD is provided by Bloomberg Philanthropies. The Met: Live in HD series is supported by Rolex. -

LA REVUE HEBDOMADAIRE, 11 Février 1893, Pp. 296-309. on Sait L

LA REVUE HEBDOMADAIRE , 11 février 1893, pp. 296-309. On sait l’activité surprenante de M. Massenet et son ardeur au travail. Représente-t-on une œuvre nouvelle signée de son nom, on est sûr d’apprendre en même temps qu’il est en train d’en achever une autre. A peine l’Opéra-Comique vient-il de nous donner Werther que déjà nous savons que Thaïs est terminée. Aussi la liste des opéras de M. Massenet est-elle déjà longue, et il est certain que le compositeur à qui nous devons le Roi de Lahore, Hérodiade, le Cid, Esclarmonde, Manon, le Mage et Werther, ne saurait en aucun cas être accusé de perdre son temps. Cette inépuisable fécondité entraîne avec elle ses avantages et ses inconvénients. Mais nous croyons qu’en ce qui concerne M. Massenet, elle a moins d’inconvénients que d’avantages. Tandis que certains tempéraments d’artistes ont besoin, en effet, d’une longue gestation préalable, pour exprimer leurs idées et leur donner une forme, il est de ces natures spécialement douées qui abordent tous les sujets comme en se jouant et savent en vertu de leur admirable souplesse se les approprier en les accommodant à leurs facultés. Est-il besoin de dire que M. Massenet a été doté par une bonne fée d’une de ces natures toutes d’impulsion, et qu’il n’est pas de ceux qui mûrissent laborieusement leurs œuvres? Mais // 297 // sa personnalité s’accommode à merveille de cette production infatigable, et cette fécondité même n’en est pas un des côtés les moins caractéristiques. -

KING FM SEATTLE OPERA CHANNEL Featured Full-Length Operas

KING FM SEATTLE OPERA CHANNEL Featured Full-Length Operas GEORGES BIZET EMI 63633 Carmen Maria Stuarda Paris Opera National Theatre Orchestra; René Bologna Community Theater Orchestra and Duclos Chorus; Jean Pesneaud Childrens Chorus Chorus Georges Prêtre, conductor Richard Bonynge, conductor Maria Callas as Carmen (soprano) Joan Sutherland as Maria Stuarda (soprano) Nicolai Gedda as Don José (tenor) Luciano Pavarotti as Roberto the Earl of Andréa Guiot as Micaëla (soprano) Leicester (tenor) Robert Massard as Escamillo (baritone) Roger Soyer as Giorgio Tolbot (bass) James Morris as Guglielmo Cecil (baritone) EMI 54368 Margreta Elkins as Anna Kennedy (mezzo- GAETANO DONIZETTI soprano) Huguette Tourangeau as Queen Elizabeth Anna Bolena (soprano) London Symphony Orchestra; John Alldis Choir Julius Rudel, conductor DECCA 425 410 Beverly Sills as Anne Boleyn (soprano) Roberto Devereux Paul Plishka as Henry VIII (bass) Royal Philharmonic Orchestra and Ambrosian Shirley Verrett as Jane Seymour (mezzo- Opera Chorus soprano) Charles Mackerras, conductor Robert Lloyd as Lord Rochefort (bass) Beverly Sills as Queen Elizabeth (soprano) Stuart Burrows as Lord Percy (tenor) Robert Ilosfalvy as roberto Devereux, the Earl of Patricia Kern as Smeaton (contralto) Essex (tenor) Robert Tear as Harvey (tenor) Peter Glossop as the Duke of Nottingham BRILLIANT 93924 (baritone) Beverly Wolff as Sara, the Duchess of Lucia di Lammermoor Nottingham (mezzo-soprano) RIAS Symphony Orchestra and Chorus of La Scala Theater Milan DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 465 964 Herbert von -

Hérodiade Herodiade Page 1 of 3 Opera Assn

San Francisco War Memorial 1994Hérodiade Herodiade Page 1 of 3 Opera Assn. Opera House This production is made possible by generous gifts from Mr. and Mrs. Gorham B. Knowles and Mr. and Mrs. Alfred S. Wilsey Hérodiade (in French) Opera in four acts by Jules Massenet Libretto by Paul Milliet and Henry Grémont Based on a story by Gustave Flaubert Supertitles provided by a generous gift from the Langendorf Foundation Conductor CAST Valery Gergiev Phanuel, a Chaldean Kenneth Cox Paul Ethuin (11/23.25)† Salomé Renée Fleming Production Hérode ((Herod), King of Galilee Juan Pons Lotfi Mansouri Hérodiade (Herodias), wife of Hérode Dolora Zajick* Designer Jean (John the Baptist) Plácido Domingo* Gerard Howland John Keyes (11/23,25) Costume Designer A Young Babylonian Kristin Clayton Maria-Luise Walek Vitellius, Roman Proconsul Hector Vásquez Lighting Designer A Voice in the Temple Alfredo Portilla Thomas J. Munn High Priest Eduardo del Campo Assistant to Lotfi Mansouri Charles Roubaud Chorus Director *Role debut †U.S. opera debut Ian Robertson PLACE AND TIME: Jerusalem, 30 A.D. Choreographer Victoria Morgan Assistant to Maestro Gergiev Peter Grunberg Musical Preparation Robert Morrison Bryndon Hassman Kathleen Kelly Svetlana Gorzhevskaya Philip Eisenberg Prompter Philip Eisenberg Assistant Stage Director Paula Williams Paula Suozzi Stage Manager Theresa Ganley Fight Coordinator Larry Henderson Supertitles Clifford Cranna Tuesday, November 8 1994, at 8:00 PM Act I -- Hérode's palace Saturday, November 12 1994, at 8:00 PM INTERMISSION Tuesday, November 15 1994, at 7:30 PM Act II, Scene 1 -- Hérode's chambers Friday, November 18 1994, at 8:00 PM Act II, Scene 2 -- The grand square in Jerusalem Sunday, November 20 1994, at 2:00 PM INTERMISSION Wednesday, November 23 1994, at 7:30 PM Act III, Scene 1 -- Phanuel's rooms Friday, November 25 1994, at 8:00 PM Act III, Scene 2 -- Palace courtyard Act III, Scene 3 -- The temple Act IV, Scene 1 -- Prison Act IV, Scene 2 -- Great hall of the palace San Francisco War Memorial 1994Hérodiade Herodiade Page 2 of 3 Opera Assn. -

Newsletter • Bulletin

NATIONAL CAPITAL OPERA SOCIETY • SOCIETE D'OPERA DE LA CAPITALE NATIONALE Newsletter • Bulletin Summer 2000 L’Été A WINTER OPERA BREAK IN NEW YORK by Shelagh Williams The Sunday afternoon programme at Alice Tully Having seen their ads and talked to Helen Glover, their Hall was a remarkable collaboration of poetry and words new Ottawa representative, we were eager participants and music combining the poetry of Emily Dickinson in the February “Musical Treasures of New York” ar- recited by Julie Harris and seventeen songs by ten dif- ranged by Pro Musica Tours. ferent composers, sung by Renee Fleming. A lecture We left Ottawa early Saturday morning in our bright preceded the concert and it was followed by having most pink (and easily spotted!) 417 Line Bus and had a safe of the composers, including Andre Previn, join the per- and swift trip to the Belvedere Hotel on 48th St. Greeted formers on stage for the applause. An unusual and en- by Larry Edelson, owner/director and tour leader, we joyable afternoon. met our fellow opera-lovers (six from Ottawa, one from Monday evening was the Met’s block-buster pre- Toronto, five Americans and three ladies from Japan) at miere production of Lehar’s The Merry Widow, with a welcoming wine and cheese party. Frederica von Stade and Placido Domingo, under Sir Saturday evening the opera was Offenbach’s Tales Andrew Davis, in a new English translation. The oper- of Hoffmann. This was a lavish (though not new) pro- etta was, understandably, sold out, and so the only tick- duction with sumptuous costumes, sets descending to ets available were seats in the Family Circle (at the very reappear later, and magical special effects. -

ESCLARMONDE Opera in 4 Acts (With Prologue & Epilogue) Music

ESCLARMONDE Opera in 4 acts (with prologue & Epilogue) Music by Jules Massenet Libretto by Alfred Blau & Louis de Gramont First Performance: Opéra, Paris, May 14, 1889 Prologue. There is no overture or prelude. the curtain rises abruptly on the Basilica in Byzantium, before the closed doors of the sanctuary. The court of the Emperor Phorcas, who is both ruler and magician, is gathered to witness his abdication in favor of his daughter Esclarmonde. Phorcas reveals that he has instructed Esclarmonde in the mysteries of his magical powers, but he imposes the condition that if she is to retain these powers and her throne, she must remain veiled to all men until she reaches the age of twenty. Then a tournament will be held, and the winner will be awarded her hand in marriage and will share her power as ruler of Byzantium. The doors of the sanctuary open. the veiled, richly garbed and bejewelled. Esclarmonde appears, accompanied by her sister Parséis to act as the guardian of her sister, and then, bidding farewell to all, he hands over his crown and scepter to Esclarmonde amid the acclamations of the assembled court. Act I. A terrace of the palace, Esclarmonde is musing on her feelings for Roland, a French knight when she once saw and fell in love with, unbeknown to him. When Parséis joins her and remarks on her tears, she confesses that she feels her father's conditions have condemned her to a life of loneliness. Parséis suggests that with her magic powers she can choose her eventual husband; then, learning that she is in love with Roland, suggests that she uses her powers to bring him to her. -

Hérodiade H Ér O D Ia

LIVRET DE PAUL MILLIET ET D’HENRI GRÉMONT INSPIRÉ D’HÉRODIAS DE GUSTAVE FLAUBERT CRÉATION LE 19 DÉCEMBRE 1881 À BRUXELLES DIRECTION MUSICALE JEAN-YVES OSSONCE MISE EN SCÈNE JEAN-LOUIS PICHON HÉRODIADE DÉCORS ET COSTUMES JÉRÔME BOURDIN LUMIÈRES MICHEL THEUIL COPRODUCTION OPÉRA DE SAINT-ÉTIENNE, OPÉRA DE MARSEILLE HÉRODIADE OPERA.SAINT-ETIENNE.FR SAISON 2018-2019 HÉRODIADE PASSEZ LE RÉVEILLON À L’OPÉRA ! IL BARBIERE DI SIVIGLIA OPÉRA BOUFFE EN 2 ACTES GIOACCHINO ROSSINI Adapté de la première pièce de la « Trilogie de Figaro » de Beaumarchais, le livret de Sterbini met en scène un comte Almaviva amoureux, tentant de séduire la belle Rosina enfermée par son oncle Bartolo. Pour parvenir à ses fins, le comte n’hésitera pas à se servir du talent pour la ruse du barbier Figaro, qui l’entraînera dans des plans rocambolesques. Malgré une première devenue légendaire par sa débâcle, l’opéra de Rossini s’affirme comme une œuvre majeure : revisitant les canons de l’opera buffa et poussant le genre dans ses derniers retranchements, 2 I Le Barbier de Séville impressionne toujours. Alliant à la virtuosité du bel canto le raffinement de l’opera seria, l’écriture vocale de Rossini est d’une grande habileté mélodique. Composée très rapidement, l’œuvre se savoure comme une musique de l’instant ; Rossini a su allier un langage généreux et une écriture précise, donnant à l’auditeur l’illusion de la spontanéité. Cette œuvre est aussi l’occasion de découvrir une Rosina mutine et effrontée, très éloignée de la comtesse des Noces de Figaro. SAM. 29 DÉC. -

Roberto Abbado Elīnarevive Garanča Orquestra De La Comunitat Valenciana Roberto Abbado

Revive ElīnA GARAnčA Orquestra de la Comunitat Valenciana ROBERTO ABBADO ElīnaRevive GARANča Orquestra de la Comunitat Valenciana ROBERTO ABBADO 2 PIETRO MASCAGNI (1863–1945) MODEST MUSSORGSKY (1839–1881) Cavalleria rusticana Boris Godunov Libretto: Giovanni Targioni-Tozzetti, Guido Menasci ed. Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov · Libretto: Modest Mussorgsky A “Voi lo sapete, o mamma” (Santuzza) 3:38 F “Skučno Marine … Kak tomitel’no i vyalo” (Marina) 4:09 FRANCESCO CILEA (1866–1950) FRANCESCO CILEA Adriana Lecouvreur Adriana Lecouvreur Libretto: Arturo Colautti G “Ecco: respiro appena … Io son l’umile ancella” (Adriana) 3:38 B “Acerba voluttà, dolce tortura … O vagabonda stella d’Oriente” 4:14 (la principessa di Bouillon) JULES MASSENET (1842–1912) Hérodiade HECTOR BERLIOZ (1803–1869) Libretto: Paul Milliet, Henri Grémont [Georges Hartmann] Les Troyens H “Venge-moi d’une suprême offense ! … Ne me refuse pas” 6:35 Libretto: Hector Berlioz (Hérodiade) C “Ah ! Ah ! Je vais mourir … Adieu, fière cité” (Didon) 6:45 AmbROISE ThOMAS (1811–1896) GIUSEppE VERDI (1813–1901) Mignon Don Carlo Libretto: Jules Barbier, Michel Carré Libretto: Joseph Méry, Camille du Locle I “Connais-tu le pays” (Mignon) 5:46 Italian libretto: Achille de Lauzières, Angelo Zanardini D “Nel giardin del bello” (Eboli, Tebaldo, coro) 4:44 GIUSEPPE VERDI Canzone del velo · The Veil Song · Lied vom Schleier · Chanson du voile La forza del destino with JENNIFER O’loUGHLIN soprano (Tebaldo) Libretto: Francesco Maria Piave, Antonio Ghislanzoni J “Rataplan, rataplan, rataplan” (Preziosilla, -

Appropriations of Gregorian Chant in Fin-De-Siècle French Opera: Couleur Locale – Message-Opera – Allusion?

Journal of the Royal Musical Association, 145/1, 37–74 doi:10.1017/rma.2020.7 Appropriations of Gregorian Chant in Fin-de-siècle French Opera: Couleur locale – Message-Opera – Allusion? BENEDIKT LESSMANN Abstract This article compares three French operas from the fin de siècle with regard to their appropriation of Gregorian chant, examining their different ideological and dramaturgical impli- cations. In Alfred Bruneau’s Le rêve (1891), the use of plainchant, more or less in literal quotation and an accurate context, has often been interpreted as naturalistic. By treating sacred music as a world of its own, Bruneau refers to the French idea of Gregorian chant as ‘other’ music. In Vincent d’Indy’s L’étranger (1903), a quotation of Ubi caritas does not serve as an occasional illustration, but becomes essential as part of the leitmotif structure, thus functioning as the focal point of a religious message. Jules Massenet’s Le jongleur de Notre-Dame (1902) provides a third way of using music associated with history and Catholicism. In this collage of styles, plainchant is not quoted literally, but rather alluded to, offering in this ambiguity a mildly anti-clerical satire. Thus, through an exchange, or rather through a bizarre and unfortunate reversal, church music in the theatre is more ecclesiastical than in the church itself. Camille Bellaigue1 In an article in the Revue des deux mondes of 1904, the French critic Camille Bellaigue described the incorporation of church music into contemporary opera, referring to anticipated examples by Meyerbeer and Gounod; to works less well known today, such as Lalo’s Le roi d’Ys (which quotes the Te Deum); and also (quite extensively) to Wagner’s Parsifal, the ‘masterpiece […] or the miracle of theatrical art that is not only Email: [email protected] I am grateful to Stefan Keym for his support and advice with my doctoral studies and beyond. -

(“You Love Opera: We'll Go Twice a Week”), Des Grieux Promise

MANON AT THE OPERA: FROM PRÉVOST’S MANON LESCAUT TO AUBER’S MANON LESCAUT AND MASSENET’S MANON VINCENT GIROUD “Vous aimez l’Opéra: nous irons deux fois la semaine” (“You love opera: we’ll go twice a week”), Des Grieux promises Manon in Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut, as the lovers make plans for their life at Chaillot following their first reconciliation.1 Opera, in turn, has loved Manon, since there exist at least eight operatic versions of the Abbé Prévost’s masterpiece – a record for a modern classic.2 Quickly written in late 1730 and early 1731, the Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut first appeared in Amsterdam as Volume VII of Prévost’s long novel Mémoires d’un homme de qualité.3 An instantaneous success, it went 1 Abbé Prévost, Histoire du Chevalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut, ed. Frédéric Deloffre and Raymond Picard, Paris: Garnier frères, 1965, 49-50. 2 They are, in chronological order: La courtisane vertueuse, comédie mȇlée d’ariettes four Acts (1772), libretto attributed to César Ribié (1755?-1830?), music from various sources; William Michael Balfe, The Maid of Artois, grand opera in three Acts (1836), libretto by Alfred Bunn; Daniel-François-Esprit Auber, Manon Lescaut, opéra comique in three Acts (1856), libretto by Eugène Scribe; Richard Kleinmichel, Manon, oder das Schloss de l’Orme, romantic-comic opera in four Acts (1887), libretto by Elise Levi; Jules Massenet, Manon, opéra comique in five Acts and six tableaux (1884), libretto by Henri Meilhac and Philippe Gille; Giacomo Puccini, Manon Lescaut, lyrical drama in four Acts (1893), libretto by Domenico Oliva, Giulio Ricordi, Luigi Illica, Giuseppe Giacosa, and Marco Praga; and Hans Werner Henze, Boulevard Solitude, lyric drama in seven Scenes (1951), libretto by Grete Weil on a scenario by Walter Jockisch. -

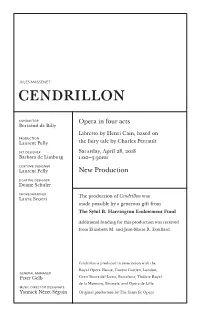

04-28-2018 Cendrillon Mat.Indd

JULES MASSENET cendrillon conductor Opera in four acts Bertrand de Billy Libretto by Henri Cain, based on production Laurent Pelly the fairy tale by Charles Perrault set designer Saturday, April 28, 2018 Barbara de Limburg 1:00–3:50 PM costume designer Laurent Pelly New Production lighting designer Duane Schuler choreographer The production of Cendrillon was Laura Scozzi made possible by a generous gift from The Sybil B. Harrington Endowment Fund Additional funding for this production was received from Elizabeth M. and Jean-Marie R. Eveillard Cendrillon is produced in association with the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; general manager Peter Gelb Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona; Théâtre Royal de la Monnaie, Brussels; and Opéra de Lille. music director designate Yannick Nézet-Séguin Original production by The Santa Fe Opera 2017–18 SEASON The 5th Metropolitan Opera performance of JULES MASSENET’S This performance cendrillon is being broadcast live over The Toll Brothers– Metropolitan Opera conductor International Radio Bertrand de Billy Network, sponsored by Toll Brothers, in order of vocal appearance America’s luxury ® homebuilder , with pandolfe the fairy godmother generous long-term Laurent Naouri Kathleen Kim support from The Annenberg madame de la haltière the master of ceremonies Foundation, The Stephanie Blythe* David Leigh** Neubauer Family Foundation, the noémie the dean of the faculty Vincent A. Stabile Ying Fang* Petr Nekoranec** Endowment for Broadcast Media, dorothée the prime minister and contributions Maya Lahyani Jeongcheol Cha from listeners worldwide. lucette, known as cendrillon prince charming Joyce DiDonato Alice Coote There is no Toll Brothers– spirits the king Metropolitan Lianne Coble-Dispensa Bradley Garvin Opera Quiz in Sara Heaton List Hall today. -

Aus Der Hand Frißt Der Herbst Mir Sein Blatt: Wir Sind Freunde

TVeR – 127 – Romania+ medial – in TV, Radio etc. | 2020-03-24 … -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- * Informationsdienst zur unmittelbaren und mittelbaren Unterstützung von Lehre und Studium der Romanistik * To whom it may concern - A quien pueda interesar - … Paul Celan (23.11.1920 Czernowitz, “Großrumänien” - 20.4.1970, Paris) Corona Aus der Hand frißt der Herbst mir sein Blatt: wir sind Freunde. Wir schälen die Zeit aus den Nüssen und lehren sie gehn: die Zeit kehrt zurück in die Schale. Im Spiegel ist Sonntag, im Traum wird geschlafen, der Mund redet wahr. Mein Aug steigt hinab zum Geschlecht der Geliebten: wir sehen uns an, wir sagen uns Dunkles, wir lieben einander wie Mohn und Gedächtnis, wir schlafen wie Wein in den Muscheln, wie das Meer im Blutstrahl des Mondes. Wir stehen umschlungen im Fenster, sie sehen uns zu von der Straße: es ist Zeit, daß man weiß! Es ist Zeit, daß der Stein sich zu blühen bequemt, daß der Unrast ein Herz schlägt. Es ist Zeit, daß es Zeit wird. Es ist Zeit. (1959) *** ¡Ojo! ¡Oiga! - Besondere Empfehlungen: So, 2020-03-29, 18:30 – 20:00 dlf-k Hörspiel | Die Verlassene. Von Honoré de Balzac So, 2020-03-29, 22:30 – 23:00 dlf-k Literatur | Von Wasserhosen, Windsbräuten und Wirbelstürmen: Stürme in der Literatur. Di, 2020-03-31, 14:15 – 17:15 ZDFinfo 1491 – Amerika vor Kolumbus (1-4/4)| Doku | D 2018 Die ersten Menschen / Jäger und Bauern / Wissen und macht / Verlorene Welt *** -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- (Zusammenstellung: Svend Plesch, Institut für Romanistik, Universität Rostock) Nach Sender-Angaben – Änderungen / Abweichungen sind möglich. „Irrtum vorbehalten“. | Seite 1 von 37 TVeR – 127 – Romania+ medial – in TV, Radio etc.