Where Do Youth Smokers Get Their Cigarettes?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Project SUN: a Study of the Illicit Cigarette Market In

Project SUN A study of the illicit cigarette market in the European Union, Norway and Switzerland 2017 Results Executive Summary kpmg.com/uk Important notice • This presentation of Project SUN key findings (the ‘Report’) has been prepared by KPMG LLP the UK member firm (“KPMG”) for the Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies (RUSI), described in this Important Notice and in this Report as ‘the Beneficiary’, on the basis set out in a private contract dated 27 April 2018 agreed separately by KPMG LLP with the Beneficiary (the ‘Contract’). • Included in the report are a number of insight boxes which are written by RUSI, as well as insights included in the text. The fieldwork and analysis undertaken and views expressed in these boxes are RUSI’s views alone and not part of KPMG’s analysis. These appear in the Foreword on page 5, the Executive Summary on page 6, on pages 11, 12, 13 and 16. • Nothing in this Report constitutes legal advice. Information sources, the scope of our work, and scope and source limitations, are set out in the Appendices to this Report. The scope of our review of the contraband and counterfeit segments of the tobacco market within the 28 EU Member States, Switzerland and Norway was fixed by agreement with the Beneficiary and is set out in the Appendices. • We have satisfied ourselves, so far as possible, that the information presented in this Report is consistent with our information sources but we have not sought to establish the reliability of the information sources by reference to other evidence. -

Creating a Future Free from Smoking, Vaping and Nicotine Extraordinary Achievements in a Year Like No Other

CREATING A FUTURE FREE FROM SMOKING, VAPING AND NICOTINE EXTRAORDINARY ACHIEVEMENTS IN A YEAR LIKE NO OTHER 2020 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS 03 LETTER FROM THE CEO & PRESIDENT 05 YOUTH & YOUNG ADULT PUBLIC EDUCATION 13 RESEARCH & POLICY 21 COMMUNITY & YOUTH ENGAGEMENT 28 INNOVATIONS TO QUIT SMOKING, VAPING, AND NICOTINE 34 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS & BOARD OF DIRECTORS LETTER FROM CEO & PRESIDENT ROBIN KOVAL 2020 was a year like no other. In the face of a global powerful, comprehensive umbrella for all our youth- pandemic and unimaginable challenges, Truth facing national programs which have expanded Initiative remained laser-focused on its ultimate beyond prevention to include, cessation, education goal: saving lives. We intensified our efforts to and activism initiatives. In 2020, we launched six combat tobacco use as both a public health and truth campaign efforts with record engagement, social justice issue. We rapidly responded to including our first campaigns to fully integrate This national crises by providing our young audience is Quitting, our first-of-its-kind, free and anonymous with information to stay safe, healthy and to help text message quit vaping program tailored to young their communities, while working tirelessly to people. With more than 300,000 young people create a future that has never been more urgent: enrolled and strong results from our randomized one where tobacco and nicotine addiction are clinical trial — the first-ever for a quit vaping things of the past. As youth e-cigarette use persists intervention — This is Quitting is making a big impact. at epidemic levels and threatens to addict a new We brought the power of truth and This is Quitting generation to nicotine, we continue to lead the fight to classrooms and communities with Vaping: Know against tobacco use in all forms and launched an the truth, our first national youth vaping prevention update to our organization’s mission: achieve a curriculum that nearly 55,000 students have already culture where young people reject smoking, vaping, completed in just its first five months. -

Child Labor Rules for Employing Youth in Restaurants and Quick-Service Establishments Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)

U.S. Department of Labor Wage and Hour Division (July 2010) Fact Sheet #2A: Child Labor Rules for Employing Youth in Restaurants and Quick-Service Establishments Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) This fact sheet provides general information concerning the application of the federal child labor provisions to restaurants and quick-service establishments that employ workers who are less than 18 years of age. For detailed information about the federal youth provisions, please read Regulations, 29 CFR Part 570. The Department of Labor is committed to helping young workers find positive, appropriate, and safe employment experiences. The child labor provisions of the FLSA were enacted to ensure that when young people work, the work does not jeopardize their health, well-being, or educational opportunities. Working youth are generally entitled to the same minimum wage and overtime protections as older adults. For information about the minimum wage and overtime e requirements in the restaurant and quick-service industries, please see Fact Sheet # 2 in this series, Restaurants and Quick Service Establishment under the Fair Labor Standards Act. Minimum Age Standards for Employment The FLSA and the child labor regulations, issued at 29 CFR Part 570, establish both hours and occupational standards for youth. Youth of any age are generally permitted to work for businesses entirely owned by their parents, except those under 16 may not be employed in mining or manufacturing and no one under 18 may be employed in any occupation the Secretary of Labor has declared to be hazardous. 18 Years Once a youth reaches 18 years of age, he or she is no longer subject to the federal of Age child labor provisions. -

Annex 2: Description of the Tobacco Market, Manufacturing of Cigarettes

EUROPEAN COMMISSION Brussels, 19.12.2012 SWD(2012) 452 final Part 3 COMMISSION STAFF WORKING DOCUMENT IMPACT ASSESSMENT Accompanying the document Proposal for a DIRECTIVE OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the Member States concerning the manufacture, presentation and sale of tobacco and related products (Text with EEA relevance) {COM(2012) 788 final} {SWD(2012) 453 final} EN EN A.2 DESCRIPTION OF THE TOBACCO MARKET, MANUFACTURING OF CIGARETTES AND THE MARKET OF RELATED NON-TOBACCO PRODUCTS A.2.1. The tobacco market.................................................................................................. 1 A.2.1.1. Tobacco products.............................................................................................. 1 A.2.1.2. Tobacco manufacturing .................................................................................... 6 A.2.1.3. Tobacco growing .............................................................................................. 8 A.2.1.4. Tobacco distribution levels............................................................................... 9 A.2.1.5. Upstream/downstream activities..................................................................... 10 A.2.1.6. Trade............................................................................................................... 10 A.2.2. Tobacco and Society............................................................................................... 11 A.2.2.1. -

Download Issue

YOUTH &POLICY No. 116 MAY 2017 Youth & Policy: The final issue? Towards a new format Editorial Group Paula Connaughton, Ruth Gilchrist, Tracey Hodgson, Tony Jeffs, Mark Smith, Jean Spence, Naomi Thompson, Tania de St Croix, Aniela Wenham, Tom Wylie. Associate Editors Priscilla Alderson, Institute of Education, London Sally Baker, The Open University Simon Bradford, Brunel University Judith Bessant, RMIT University, Australia Lesley Buckland, YMCA George Williams College Bob Coles, University of York John Holmes, Newman College, Birmingham Sue Mansfield, University of Dundee Gill Millar, South West Regional Youth Work Adviser Susan Morgan, University of Ulster Jon Ord, University College of St Mark and St John Jenny Pearce, University of Bedfordshire John Pitts, University of Bedfordshire Keith Popple, London South Bank University John Rose, Consultant Kalbir Shukra, Goldsmiths University Tony Taylor, IDYW Joyce Walker, University of Minnesota, USA Anna Whalen, Freelance Consultant Published by Youth & Policy, ‘Burnbrae’, Black Lane, Blaydon Burn, Blaydon on Tyne NE21 6DX. www.youthandpolicy.org Copyright: Youth & Policy The views expressed in the journal remain those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Editorial Group. Whilst every effort is made to check factual information, the Editorial Group is not responsible for errors in the material published in the journal. ii Youth & Policy No. 116 May 2017 About Youth & Policy Youth & Policy Journal was founded in 1982 to offer a critical space for the discussion of youth policy and youth work theory and practice. The editorial group have subsequently expanded activities to include the organisation of related conferences, research and book publication. Regular activities include the bi- annual ‘History of Community and Youth Work’ and the ‘Thinking Seriously’ conferences. -

Current Population Survey, July 2018: Tobacco Use Supplement File That Becomes Available After the File Is Released

CURRENT POPULATION SURVEY, July 2018 Tobacco Use Supplement FILE Version 2, Revised September 2020 TECHNICAL DOCUMENTATION CPS—18 This file documentation consists of the following materials: Attachment 1 Abstract Attachment 2 Overview - Current Population Survey Attachment 3a Overview – July 2018 Tobacco Use Supplement Attachment 3b Overview-Tobacco Use Supplement NCI Data Harmonization Project Attachment 4 Glossary Attachment 5 How to Use the Record Layout Attachment 6 Basic CPS Record Layout Attachment 7 Current Population Survey, July 2018 Tobacco Use Supplement Record Layout Attachment 8 Current Population Survey, July 2018 Tobacco Use Supplement Questionnaire Attachment 9 Industry Classification Codes Attachment 10 Occupation Classification Codes Attachment 11 Specific Metropolitan Identifiers Attachment 12 Topcoding of Usual Hourly Earnings Attachment 13 Tallies of Unweighted Counts Attachment 14 Countries and Areas of the World Attachment 15 Allocation Flags Attachment 16 Source and Accuracy of the July 2018 Tobacco Use Supplement Data Attachment 17 User Notes NOTE Questions about accompanying documentation should be directed to Center for New Media and Promotions Division, Promotions Branch, Bureau of the Census, Washington, D.C. 20233. Phone: (301) 763-4400. Questions about the CD-ROM should be directed to The Customer Service Center, Bureau of the Census, Washington, D.C. 20233. Phone: (301) 763-INFO (4636). Questions about the design, data collection, and CPS-specific subject matter should be directed to Tim Marshall, Demographic Surveys Division, Bureau of the Census, Washington, D.C. 20233. Phone: (301) 763-3806. Questions about the TUS subject matter should be directed to the National Cancer Institute’s Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, Behavior Research Program at [email protected] ABSTRACT The National Cancer Institute (NCI) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the U.S. -

CIGARETTE SMUGGLING Wednesday, 22 January 2014 9:00 - 12:30 Altiero Spinelli Building, Room ASP 5G3

DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES POLICY DEPARTMENT D: BUDGETARY AFFAIRS WORKSHOP ON CIGARETTE SMUGGLING Wednesday, 22 January 2014 9:00 - 12:30 Altiero Spinelli Building, Room ASP 5G3 PE490.681 18/01/2014 EN TABLE OF CONTENTS WORKSHOP PROGRAMME 5 EU POLICY AND ILLICIT TOBACCO TRADE: ASSESSING THE IMPACTS 7 Briefing Paper by Luk Joossens, Hana Ross and Michał Stokłosa EU AGREEMENTS WITH FOUR CIGARETTE MANUFACTURERS - MAIN 56 FACTS Table by Policy Department D ANNEX I: BIOGRAPHIES OF INVITED SPEAKERS 57 ANNEX II: PRESENTATIONS 66 Presentation by Leszek Bartłomiejczyk Presentation by Luk Joossens, Hana Ross and Michał Stokłosa 3 WORKSHOP ON CCIGARETTE SSMUGGLING Organised by the Policy Department D on Budgetary Affairs Wednesday, 22 January 2014, 9:00 - 12:30 European Parliament, Brussels Altiero Spinelli Building, Room ASP 5G3 DRAFT WORKSHOP PROGRAMME 9:00 - 9:10 Welcome and Introduction 9:00 - 9:05 Welcome by Michael Theurer 5 minutes Chair of the Committee on Budgetary Control 9:05 - 9:10 Introduction by Bart Staes 5 minutes Vice-Chair of the Committee on Budgetary Control ___________________________________________________________ 9:10 - 9:25 First speaker: Prof. Anna Gilmore (UK) Director, Tobacco Control Research Group (University of Bath) - evaluate impact of public health policy and the impact of broader policy changes. Part of UK Centre for Tobacco Control Studies (UKCTCS): The Current State of Smuggling of Cigarettes Followed by Q&A (15min) 9:40 - 9.55 Second speaker: Aamir Latif The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ): Terrorism and Tobacco: Extremists, Insurgents Turn to Cigarette Smuggling Followed by Q&A (15min) Programme version dated 26 November 2013, updated 09/01/2014 DV/1014866EN PE490.681v01-00 5 10:10 - 10:25 Third speaker: Howard Pugh (EUROPOL) Project Manager AWF Smoke: How Does EUROPOL Contribute to the Fight Against Global Cigarette Smuggling? Followed by Q&A (15min) 10:40 - 10:55: Fourth speaker: Leszek Bartłomiejczyk Warsaw School of Economics, expert in excise duties and border control, team of Prof. -

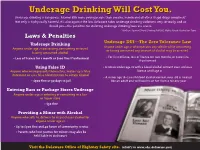

Underage Drinking Will Cost You

UnderageUnderage DrinkingDrinking WillWill CostCost You.You. Underage drinking is dangerous. Alcohol kills more young people than cocaine, heroin and all other illegal drugs combined.* Not only is it physically harmful, it’s also against the law. Delaware takes underage drinking violations very seriously, and so should you—the penalties for violating underage drinking laws are severe. * Mothers Against Drunk Driving (MADD): Myths About Alcohol for Teens Laws & Penalties Underage DUI—The Zero Tolerance Law Underage Drinking Underage DUI—The Zero Tolerance Law Anyone under age 21 who operates any vehicle while consuming Anyone under age 21 possessing, consuming or found or having consumed any amount of alcohol may be arrested. having consumed alcohol • Loss of license for 1 month or $100 fine if unlicensed • For first offense, loss of license for two months, or $200 fine if unlicensed Using False ID • A minor under age 18 with a blood alcohol content over .08 loses Anyone who misrepresents themselves, makes up a false license until age 21 statement or uses false identification to obtain alcohol • A minor age 18–21 with blood alcohol content over .08 is treated • $500 fine or 30 days in jail like an adult and will lose his or her license for one year Entering Bars or Package Stores Underage Anyone under age 21 entering or remaining in a bar or liquor store • $50 fine Providing a Minor with Alcohol Anyone who sells to, delivers to or purchases alcohol for anyone under age 21 • Up to $500 fine and 40 hours of community service • Parents who host parties for minors may also be held liable in civil court Visit the Delaware Office of Highway Safety site. -

Democracy Studies

Democracy Studies Democracy Studies Program website The goal of the Democracy Studies area (DMST) is to help students explore and critically examine the foundations, structures and purposes of diverse democratic institutions and practices in human experience. Democracy Studies combines a unique appreciation of Maryland’s democratic roots at St. Mary’s City with contemporary social and political scholarship, to better understand the value of democratic practices to human functioning and the contribution of democratic practices to a society’s development. The primary goal of the program of study is to provide students with a deeper understanding of how democracies are established, instituted and improved. Any student with an interest in pursuing the cross-disciplinary minor in Democracy Studies should consult with the study area coordinator or participating faculty member. Students are encouraged to declare their participation and intent to minor in the area as soon as possible, and no later than the end of the first week of the senior year. To successfully complete the cross-disciplinary minor in Democracy Studies, a student must satisfy the following requirements, designed to provide the depth and breadth of knowledge consistent with the goals of the field: Degree Requirements for the Minor General College Requirements General College requirements All requirements in a major field of study Required Courses At least 22 credit hours in courses approved for Democracy Studies, with a grade of C- or higher, including: HIST 200 (U.S. History, 1776-1980) or HIST 276 (20th Century World) or POSC 262 (Introduction to Democratic Political Thought) Additional courses from three different disciplines cross-listed with Democracy Studies to total 12 credit hours. -

Fiscal Impact Report Deschutes County

July 2017 Deschutes County Fiscal Impact Report Acknowledgments July 2017 This report was produced by the Rede Group for Deschutes County Health Services (DCHS). Stephanie Young-Peterson, MPH Robb Hutson, MA Erin Charpentier, MFA Caralee Oakey We would like to thank the following for their contribution to this project: Penny Pritchard, MPH This project was made possible through Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement grant funding provided by the State of Oregon, Oregon Health Authority to implement tobacco prevention and education Strategies for Policy And enviRonmental Change, Tobacco-Free (SPArC Tobacco-Free). Table of Contents Contents: Background & Introduction....................................................1 Retailer Survey Findings........................................................5 Estimation of TRL Implementation & Enforcement Costs.....15 Conclusion and Committee Recommendation...................21 How Other Jurisdictions are Tackling the Problem.................22 End Notes ..........................................................................23 Appendix: A. Timeline of TRL policy work..........................................26 B. Lane County TRL Ordinance.........................................27 C. Lane County TRL Application........................................37 D. Lane County TRL Inspection Form.................................38 E. Multnomah County TRL Ordinance...............................39 F. Multnomah County TRL Application.............................44 G. Multnomah County TRL Inspection Form......................48 -

Tobacco Pack Display in New Zealand After the Introduction of Standardised Packaging

Now we see them, now we don’t: Tobacco pack display in New Zealand after the introduction of standardised packaging Fourth Year Medical Student Project by Group A2 Kirsty Sutherland, Johanna Nee-Nee, Rebecca Holland, Miriam Wilson, Samuel Ackland, Claudia Bocock, Abbey Cartmell, Jack Earp, Christina Grove, Charlotte Hewson, Will Jefferies, Lucy Keefe, Jamie Lockyer, Saloni Patel, Miguel Quintans, Michael Robbie, Lauren Teape, Jess Yang June 2018 Abstract Introduction In March 2018, Government started a transition to a standardised packaging policy, to help reduce the prevalence of smoking and the heavy burden it has on health and health inequalities in New Zealand. The aims of our study were: (i) to contribute to the evaluation of the impact of standardised tobacco packaging in NZ by repeating a previous published study on smoking and tobacco packaging display at outdoor areas of Wellington hospitality venues; (ii) contextualising this intervention for Māori health and reducing health inequalities; (iii) assessing the prevalence of vaping at these same venues and (iv) assessing the prevalence of smoking and vaping while walking at selected locations. Methods The methods followed a very similar study conducted in 2014 for largely the same venues. The field work for this study was conducted from 16 May to 27 May 2018. Observations of smokers, vapers and tobacco packs were made at 56 hospitality venues in central Wellington, along three main boulevards; Cuba Street, Courtenay Place and the Waterfront. Observation data were systematically collected and recorded on a standardised form. Results A total of 8191 patrons, 1113 active smokers, 114 active vapers and 889 visible packs were observed during 2422 venue observations. -

Laws Governing the Employment of Minors

LAWS GOVERNING THE EMPLOYMENT OF MINORS TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ...................................................................................................................1 School Attendance ......................................................................................................1 Minimum Age for Employment ................................................................................1 Employment Certificates and Permits ..................................................................2 Types of Employment Certificates and Permits.................................................3 Special Occupations ..................................................................................................6 Hours of Work ..............................................................................................................8 State Prohibited Occupations ............................................................................... 10 Employment Post-Childbirth ................................................................................. 12 Federally Prohibited Occupations Under 18 .................................................... 12 Hour Regulations .......................................................................................................13 Federally Prohibited Occupations Under 16 .................................................... 15 Safety and Health ..................................................................................................... 16 Minimum Wage ........................................................................................................