Protecting the Killers RIGHTS a Policy of Impunity in Punjab, India WATCH October 2007 Volume 19, No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Demons Within"

Demons Within the systematic practice of torture by inDian police a report by organization for minorities of inDia NOVEMBER 2011 Demons within: The Systematic Practice of Torture by Indian Police a report by Organization for Minorities of India researched and written by Bhajan Singh Bhinder & Patrick J. Nevers www.ofmi.org Published 2011 by Sovereign Star Publishing, Inc. Copyright © 2011 by Organization for Minorities of India. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, digital, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise or conveyed via the internet or a web site without prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Inquiries should be addressed to: Sovereign Star Publishing, Inc PO Box 392 Lathrop, CA 95330 United States of America www.sovstar.com ISBN 978-0-9814992-6-0; 0-9814992-6-0 Contents ~ Introduction: India’s Climate of Impunity 1 1. Why Indian Citizens Fear the Police 5 2. 1975-2010: Origins of Police Torture 13 3. Methodology of Police Torture 19 4. For Fun and Profit: Torturing Known Innocents 29 Conclusion: Delhi Incentivizes Atrocities 37 Rank Structure of Indian Police 43 Map of Custodial Deaths by State, 2008-2011 45 Glossary 47 Citations 51 Organization for Minorities of India • 1 Introduction: India’s Climate of Impunity Impunity for police On October 20, 2011, in a statement celebrating the Hindu festival of Diwali, the Vatican pled for Indians from Hindu and Christian communities to work together in promoting religious freedom. -

Trade Marks Journal No: 1844 , 09/04/2018 Class 19 2271711 24

Trade Marks Journal No: 1844 , 09/04/2018 Class 19 2271711 24/01/2012 SHAKUNTLA AGARWAL trading as ;AGARWAL TIMBER TRADERS VILLAGE UDAIPUR GOLA ROAD LAKHIMPUR KHERI 262701 U.P MANUFACTURER & TRADER Address for service in India/Attorney address: ASHOKA LAW OFFICE ASHOKA HOUSE 8, CENTRAL LANE, BENGALI MARKET, NEW DELHI - 110 001. Used Since :01/04/1995 DELHI PLYBOARD,HARDBOARD,FLUSHDOOR(WOOD),MICA,PLY,BLOCKBOARDS,INCLUDED IN THIS CLASS THIS IS CONDITION OF REGISTRATION THAT BOTH/ALL LABELS SHALL BE USED TOGETHER.. 2244 Trade Marks Journal No: 1844 , 09/04/2018 Class 19 2325042 02/05/2012 SH. SUNIL MITTAL trading as ;M/S. SHRI RAM INDUSTRIES VILLAGE BRAMSAR, TEHSIL RAWATSAR, DISTT.- HANUMAN GARH, RAJASTHAN - 335524 MANUFACTURERS AND MERCHANTS Address for service in India/Agents address: DELHI REGISTRATION SERVICES 85/86, GADODIA MARKET, KHARI BAOLI, DELHI - 110 006 Used Since :01/04/2010 AHMEDABAD PLASTER OF PARIS. 2245 Trade Marks Journal No: 1844 , 09/04/2018 Class 19 2338662 28/05/2012 ROHIT PANDEY 71-72, POLO GROUND, GIRWA, UDAIPUR (RAJASHTAN) . PROPRIETORSHIP FIRM Address for service in India/Attorney address: RAJEEV JAIN 17, BHARAT MATA PATH, JAMNA LAL BAJAJ MARG, C-SCHEME, JAIPUR - 302 001- RAJASTHAN Used Since :19/12/2000 AHMEDABAD MINERALS AND MANUFACTURER OF TILES, BLOCKS AND SLABS OF GRANITES, MARBLES, AGGLOMERATED MARBLES. 2246 Trade Marks Journal No: 1844 , 09/04/2018 Class 19 I.MICRO LIMESTONE Priority claimed from 25/01/2012; Application No. : MI2012C000763. ;Italy 2369681 25/07/2012 ITALCEMENTI S.p.A VIA CAMOZZI 124 24121 BERGAMO ITALY MANUFACTURERS AND MERCHANTS A COMPANY ORGANIZED AND EXISTING UNDER THE LAWS OF ITALY. -

Annual Report 2016

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 PUNJABI UNIVERSITY, PATIALA © Punjabi University, Patiala (Established under Punjab Act No. 35 of 1961) Editor Dr. Shivani Thakar Asst. Professor (English) Department of Distance Education, Punjabi University, Patiala Laser Type Setting : Kakkar Computer, N.K. Road, Patiala Published by Dr. Manjit Singh Nijjar, Registrar, Punjabi University, Patiala and Printed at Kakkar Computer, Patiala :{Bhtof;Nh X[Bh nk;k wjbk ñ Ò uT[gd/ Ò ftfdnk thukoh sK goT[gekoh Ò iK gzu ok;h sK shoE tk;h Ò ñ Ò x[zxo{ tki? i/ wB[ bkr? Ò sT[ iw[ ejk eo/ w' f;T[ nkr? Ò ñ Ò ojkT[.. nk; fBok;h sT[ ;zfBnk;h Ò iK is[ i'rh sK ekfJnk G'rh Ò ò Ò dfJnk fdrzpo[ d/j phukoh Ò nkfg wo? ntok Bj wkoh Ò ó Ò J/e[ s{ j'fo t/; pj[s/o/.. BkBe[ ikD? u'i B s/o/ Ò ô Ò òõ Ò (;qh r[o{ rqzE ;kfjp, gzBk óôù) English Translation of University Dhuni True learning induces in the mind service of mankind. One subduing the five passions has truly taken abode at holy bathing-spots (1) The mind attuned to the infinite is the true singing of ankle-bells in ritual dances. With this how dare Yama intimidate me in the hereafter ? (Pause 1) One renouncing desire is the true Sanayasi. From continence comes true joy of living in the body (2) One contemplating to subdue the flesh is the truly Compassionate Jain ascetic. Such a one subduing the self, forbears harming others. (3) Thou Lord, art one and Sole. -

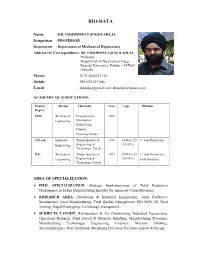

DR. INDERPREET SINGH AHUJA Designation : PROFESSOR Department : Department of Mechanical Engineering Address for Correspondence: DR

BIO-DATA Name : DR. INDERPREET SINGH AHUJA Designation : PROFESSOR Department : Department of Mechanical Engineering Address for Correspondence: DR. INDERPREET SINGH AHUJA Professor, Department of Mechanical Engg, Punjabi University, Patiala – 147002 (Punjab) Phones: 0175-3046323 (O) Mobile: 9501533113 (M) E-mail : [email protected], [email protected] ACADEMIC QUALIFICATIONS: Course/ Stream University Year %age Division Degree Ph.D. Mechanical Department of 2008 Engineering Mechanical Engineering, Punjabi University Patiala M.Tech Industrial Thapar Institute of 1998 CGPA-9.27 1st with Distinction Engineering Engineering & (83.43%) Technology, Patiala B.E. Mechanical Thapar Institute of 1993 CGPA-9.65 1st with Distinction Engineering Engineering & (86.85%) Gold Medallist Technology, Patiala AREA OF SPECIALIZATION: PH.D. SPECIALIZATION: Strategic Implementation of Total Productive Maintenance in Indian Manufacturing Industry for enhanced Competitiveness RESEARCH AREA: Production & Industrial Engineering, Total Productive Maintenance, Lean Manufacturing, Total Quality Management, ISO 9000, 5S, Hard Turning, Rapid Prototyping, Technology Management. SUBJECTS TAUGHT: Refrigeration & Air Conditioning, Industrial Engineering, Operations Research, Plant Layout & Materials Handling, Manufacturing Processes, Manufacturing Technology, Engineering Graphics, Machine Drawing, Thermodynamics, Non Traditional Machining Processes, Facilities Layout & Design. EMPLOYMENT HISTORY: Lecturer at Thapar Institute of Engineering & Technology, Patiala -

Reading Modern Punjabi Poetry: from Bhai Vir Singh to Surjit Patar

185 Tejwant S. Gill: Modern Punjabi Poetry Reading Modern Punjabi Poetry: From Bhai Vir Singh to Surjit Patar Tejwant Singh Gill Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar ________________________________________________ The paper evaluates the specificity of modern Punjabi poetry, along with its varied and multi-faceted readings by literary historians and critics. In terms of theme, form, style and technique, modern Punjabi poetry came upon the scene with the start of the twentieth century. Readings colored by historical sense, ideological concern and awareness of tradition have led to various types of reactions and interpretations. ________________________________________________________________ Our literary historians and critics generally agree that modern Punjabi poetry began with the advent of the twentieth century. The academic differences which they have do not come in the way of this common agreement. In contrast, earlier critics and historians, Mohan Singh Dewana the most academic of them all, take the modern in the sense of the new only. Such a criterion rests upon a passage of time that ushers in a new way of living. How this change then enters into poetic composition through theme, motif, technique, form, and style is not the concern of critics and historians who profess such a linear view of the modern. Mohan Singh Dewana, who was the first scholar to write the history of Punjabi literature, did not initially believe that something innovative came into being at the turn of the past century. If there was any change, it was not for the better. In his path-breaking History of Punjabi Literature (1932), he bemoaned that a sharp decline had taken place in Punjabi literature. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E2178 HON

E2178 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks October 18, 2007 At 6 p.m. on October 11, 2007, Lt. Marc many of whom will suffer from life long injuries member of the Riverside Unified School Dis- Tunstall and Ensign Jason Evans, pilot and that have no medical or technological resolu- trict Board of Education. co-pilot of a Coast Guard HH–60 Jayhawk hel- tions—including blindness, deafness, Post- Mrs. Maxine Frost graduated from Stanford icopter found the downed F/A–18 Hornet near- Traumatic Stress Disorder and Traumatic University with a bachelor’s degree in history ly 80 miles off Cape Henry, Virginia. Rescue Brain Injury. In the great State of Maryland and has been a resident and active member swimmer Petty Officer 2nd Class Mike alone, we continue to mourn the deaths of 70 of the Riverside community since 1958. Mrs. Ackermann was dispatched to retrieve the service members and our prayers go out to Frost’s interest in education began with her in- pilot from the ocean, whereupon the rescued over 392 brave men and women in uniform volvement in the education of her children. pilot was hoisted in the helicopter by flight me- who suffer from wounds gained on the battle- She was an active mother who served on var- chanic Petty Officer 3rd Class Steven Acuna. field of Iraq. ious school committees. In 1967, the Presi- The rescued pilot was transported to Sentara Mr. Speaker, as we look back over the last dent of the Riverside Unified School District Norfolk General Hospital where he is in stable five years we can only point to meager ac- Board of Education selected Maxine to fill a condition, with only minor injuries from the complishments while the overwhelming factor vacancy on the Board of Education. -

India Assessment October 2002

INDIA COUNTRY REPORT October 2003 Country Information & Policy Unit IMMIGRATION & NATIONALITY DIRECTORATE HOME OFFICE, UNITED KINGDOM India October 2003 CONTENTS 1. Scope of Document 1.1 - 1.4 2. Geography 2.1 - 2.4 3. Economy 3.1 - 3.4 4. History 4.1 - 4.16 1996 - 1998 4.1 - 4.5 1998 - the present 4.6 - 4.16 5. State Structures 5.1 - 5.43 The Constitution 5.1 - Citizenship and Nationality 5.2 - 5.6 Political System 5.7. - 5.11 Judiciary 5.12 Legal Rights/Detention 5.13 - 5.18 - Death penalty 5.19 Internal Security 5.20 - 5.26 Prisons and Prison Conditions 5.27 - 5.33 Military Service 5.34 Medical Services 5.35 - 5.40 Educational System 5.41 - 5.43 6. Human Rights 6.1 - 6.263 6.A Human Rights Issues 6.1 - 6.150 Overview 6.1 - 6.20 Freedom of Speech and the Media 6.21 - 6.25 - Treatment of journalists 6.26 – 6.27 Freedom of Religion 6.28 - 6.129 - Introduction 6.28 - 6.36 - Muslims 6.37 - 6.53 - Christians 6.54 - 6.72 - Sikhs and the Punjab 6.73 - 6.128 - Buddhists and Zoroastrians 6.129 Freedom of Assembly & Association 6.130 - 6.131 - Political Activists 6.132 - 6.139 Employment Rights 6.140 - 6.145 People Trafficking 6.146 Freedom of Movement 6.147 - 6.150 6.B Human Rights - Specific Groups 6.151 - 6.258 Ethnic Groups 6.151 - Kashmir and the Kashmiris 6.152 - 6.216 Women 6.217 - 6.238 Children 6.239 - 6.246 - Child Care Arrangements 6.247 - 6.248 Homosexuals 6.249 - 6.252 Scheduled castes and tribes 6.253 - 6.258 6.C Human Rights - Other Issues 6.259 – 6.263 Treatment of returned failed asylum seekers 6.259 - 6.261 Treatment of Non-Governmental 6.262 - 263 Organisations (NGOs) Annexes Chronology of Events Annex A Political Organisations Annex B Prominent People Annex C References to Source Material Annex D India October 2003 1. -

The Sikh Prayer)

Acknowledgements My sincere thanks to: Professor Emeritus Dr. Darshan Singh and Prof Parkash Kaur (Chandigarh), S. Gurvinder Singh Shampura (member S.G.P.C.), Mrs Panninder Kaur Sandhu (nee Pammy Sidhu), Dr Gurnam Singh (p.U. Patiala), S. Bhag Singh Ankhi (Chief Khalsa Diwan, Amritsar), Dr. Gurbachan Singh Bachan, Jathedar Principal Dalbir Singh Sattowal (Ghuman), S. Dilbir Singh and S. Awtar Singh (Sikh Forum, Kolkata), S. Ravinder Singh Khalsa Mohali, Jathedar Jasbinder Singh Dubai (Bhai Lalo Foundation), S. Hardarshan Singh Mejie (H.S.Mejie), S. Jaswant Singh Mann (Former President AISSF), S. Gurinderpal Singh Dhanaula (Miri-Piri Da! & Amritsar Akali Dal), S. Satnam Singh Paonta Sahib and Sarbjit Singh Ghuman (Dal Khalsa), S. Amllljit Singh Dhawan, Dr Kulwinder Singh Bajwa (p.U. Patiala), Khoji Kafir (Canada), Jathedar Amllljit Singh Chandi (Uttrancbal), Jathedar Kamaljit Singh Kundal (Sikh missionary), Jathedar Pritam Singh Matwani (Sikh missionary), Dr Amllljit Kaur Ibben Kalan, Ms Jagmohan Kaur Bassi Pathanan, Ms Gurdeep Kaur Deepi, Ms. Sarbjit Kaur. S. Surjeet Singh Chhadauri (Belgium), S Kulwinder Singh (Spain), S, Nachhatar Singh Bains (Norway), S Bhupinder Singh (Holland), S. Jageer Singh Hamdard (Birmingham), Mrs Balwinder Kaur Chahal (Sourball), S. Gurinder Singh Sacha, S.Arvinder Singh Khalsa and S. Inder Singh Jammu Mayor (ali from south-east London), S.Tejinder Singh Hounslow, S Ravinder Singh Kundra (BBC), S Jameet Singh, S Jawinder Singh, Satchit Singh, Jasbir Singh Ikkolaha and Mohinder Singh (all from Bristol), Pritam Singh 'Lala' Hounslow (all from England). Dr Awatar Singh Sekhon, S. Joginder Singh (Winnipeg, Canada), S. Balkaran Singh, S. Raghbir Singh Samagh, S. Manjit Singh Mangat, S. -

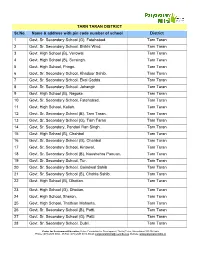

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & Address With

TARN TARAN DISTRICT Sr.No. Name & address with pin code number of school District 1 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 2 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Bhikhi Wind. Tarn Taran 3 Govt. High School (B), Verowal. Tarn Taran 4 Govt. High School (B), Sursingh. Tarn Taran 5 Govt. High School, Pringri. Tarn Taran 6 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Khadoor Sahib. Tarn Taran 7 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Ekal Gadda. Tarn Taran 8 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Jahangir Tarn Taran 9 Govt. High School (B), Nagoke. Tarn Taran 10 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Fatehabad. Tarn Taran 11 Govt. High School, Kallah. Tarn Taran 12 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Tarn Taran. Tarn Taran 13 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Tarn Taran Tarn Taran 14 Govt. Sr. Secondary, Pandori Ran Singh. Tarn Taran 15 Govt. High School (B), Chahbal Tarn Taran 16 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Chahbal Tarn Taran 17 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Kirtowal. Tarn Taran 18 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Naushehra Panuan. Tarn Taran 19 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Tur. Tarn Taran 20 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Goindwal Sahib Tarn Taran 21 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Chohla Sahib. Tarn Taran 22 Govt. High School (B), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 23 Govt. High School (G), Dhotian. Tarn Taran 24 Govt. High School, Sheron. Tarn Taran 25 Govt. High School, Thathian Mahanta. Tarn Taran 26 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (B), Patti. Tarn Taran 27 Govt. Sr. Secondary School (G), Patti. Tarn Taran 28 Govt. Sr. Secondary School, Dubli. Tarn Taran Centre for Environment Education, Nehru Foundation for Development, Thaltej Tekra, Ahmedabad 380 054 India Phone: (079) 2685 8002 - 05 Fax: (079) 2685 8010, Email: [email protected], Website: www.paryavaranmitra.in 29 Govt. -

LIST of MAHARAJA RANJIT SINGH AWARDEES 1978-1996 Sr. No

LIST OF MAHARAJA RANJIT SINGH AWARDEES 1978-1996 Sr. Name Game Year No. 1. Miss Rupa Saini Hockey 30-12-78 2. Mrs. Darshan Bhatti Hockey (Died in 2001) -do- 3. Miss Rajani Nanda Hockey -do- 4. Miss Harpreet Gill Hockey (She is gone abroad) -do- 5. Miss Nisha Sharma Hockey -do- 6. Miss Pushpinder Kaur Hockey -do- 7. Miss Kanwal Thakur Singh Badminton -do- 8. Shri B.S. Nandi Gymnastics -do- 9. Shri Manjit Singh Gymanstics -do- 10. Sh. Sushil Kohli Swimming -do- 11. Sh. Vijay Kumar Wrestling -do- 12. Sh. R.K. Randhir Singh Rifle-Shooting -do- 13. Sh. Gurbir Singh Sandhu -do- -do- 14. Sh. Gurmit Singh Sodhi -do- -do- 15. Sh. Balwant Singh Volleyball -do- 16. Sh. Kartar Singh Wrestling -do- 17. Sh. Surinder Singh Sodhi Hockey -do- 18. Sh. Gurmit Singh Boxing -do- 19. Miss Ajinder Kaur Hockey -do- 20. Miss Prema Saini -do- -do- 21. Sh. Nirmal Singh Athletics -do- 22. Sh. Ajaib Singh -do- -do- 23. Sh. Parveen Kumar -do- -do- 24. Sh. Ranjit Singh -do- -do- 25. Sh. Lehibar Singh -do- -do- 26. Sh. Gurdip Singh -do- -do- 27. Sh. Jagir Singh Volleyball 14-1-80 28. Miss Varinder Kaur -do- -do- 29. Sh. Randhir Kumar Body Building -do- 30. Sh. Manjit Singh Swimming -do- 31. Miss Nirmal Kumari Hockey -do- 32. Sh. Chanchal Singh Volleyball -do- 33. Miss Sudarshan Bajwa Hockey 1-3-81 34. Miss Parminder Kaur -do- -do- 35. Miss Kulwant Kaur -do- -do- 36. Shri Paramdeep Singh Basketball -do- 37. Shri Baldev Singh -do- -do- 38. Sh. H.S. -

The Wrestler's Body: Identity and Ideology in North India

The Wrestler’s Body Identity and Ideology in North India Joseph S. Alter UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley · Los Angeles · Oxford © 1992 The Regents of the University of California For my parents Robert Copley Alter Mary Ellen Stewart Alter Preferred Citation: Alter, Joseph S. The Wrestler's Body: Identity and Ideology in North India. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1992 1992. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft6n39p104/ 2 Contents • Note on Translation • Preface • 1. Search and Research • 2. The Akhara: Where Earth Is Turned Into Gold • 3. Gurus and Chelas: The Alchemy of Discipleship • 4. The Patron and the Wrestler • 5. The Discipline of the Wrestler’s Body • 6. Nag Panchami: Snakes, Sex, and Semen • 7. Wrestling Tournaments and the Body’s Recreation • 8. Hanuman: Shakti, Bhakti, and Brahmacharya • 9. The Sannyasi and the Wrestler • 10. Utopian Somatics and Nationalist Discourse • 11. The Individual Re-Formed • Plates • The Nature of Wrestling Nationalism • Glossary 3 Note on Translation I have made every effort to ensure that the translation of material from Hindi to English is as accurate as possible. All translations are my own. In citing classical Sanskrit texts I have referenced the chapter and verse of the original source and have also cited the secondary source of the translated material. All other citations are quoted verbatim even when the English usage is idiosyncratic and not consistent with the prose style or spelling conventions employed in the main text. A translation of single words or short phrases appears in the first instance of use and sometimes again if the same word or phrase is used subsequently much later in the text. -

Census of India 2011

Census of India 2011 PUNJAB SERIES-04 PART XII-B DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK TARN TARAN VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS PUNJAB CENSUS OF INDIA 2011 PUNJAB SERIES-04 PART XII - B DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK TARN TARAN VILLAGE AND TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT (PCA) Directorate of Census Operations PUNJAB MOTIF GURU ANGAD DEV GURUDWARA Khadur Sahib is the sacred village where the second Guru Angad Dev Ji lived for 13 years, spreading the universal message of Guru Nanak. Here he introduced Gurumukhi Lipi, wrote the first Gurumukhi Primer, established the first Sikh school and prepared the first Gutka of Guru Nanak Sahib’s Bani. It is the place where the first Mal Akhara, for wrestling, was established and where regular campaigns against intoxicants and social evils were started by Guru Angad. The Stately Gurudwara here is known as The Guru Angad Dev Gurudwara. Contents Pages 1 Foreword 1 2 Preface 3 3 Acknowledgement 4 4 History and Scope of the District Census Handbook 5 5 Brief History of the District 7 6 Administrative Setup 8 7 District Highlights - 2011 Census 11 8 Important Statistics 12 9 Section - I Primary Census Abstract (PCA) (i) Brief note on Primary Census Abstract 16 (ii) District Primary Census Abstract 21 Appendix to District Primary Census Abstract Total, Scheduled Castes and (iii) 29 Scheduled Tribes Population - Urban Block wise (iv) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Castes (SC) 37 (v) Primary Census Abstract for Scheduled Tribes (ST) 45 (vi) Rural PCA-C.D. blocks wise Village Primary Census Abstract 47 (vii) Urban PCA-Town wise Primary Census Abstract 133 Tables based on Households Amenities and Assets (Rural 10 Section –II /Urban) at District and Sub-District level.