Kok, Yoon Sing.Pdf (779.0Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Carroll News-Vol. 83, No. 2

John Carroll University Carroll Collected The aC rroll News Student 9-10-1992 The aC rroll News-Vol. 83, No. 2 John Carroll University Follow this and additional works at: http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews Recommended Citation John Carroll University, "The aC rroll News-Vol. 83, No. 2" (1992). The Carroll News. 1042. http://collected.jcu.edu/carrollnews/1042 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student at Carroll Collected. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aC rroll News by an authorized administrator of Carroll Collected. For more information, please contact [email protected]. •What presidential candidates aren't saying- FORUM page 3 •Where to find classical movie on campus- CAMPUS LIFE page 7 • Roger Waters returns after Pink Floyd, with new album ENTERTAINMENT page 9 •Interview with Alma's head football coach. Jim Cole SPORTS page 10 Federal law requires security report Tara Schmidtke of reporung cnmes to the police Ed.tortOI Edtror for federal record, ha<; not changed According to John Carroll Campus Secunty's method of University's reccntl}-relcased deahng With cnmmal Instances 1992 Annual Secu11ty Report, on campus. "We'll be domg the there were no reported murders, same thing as we thd m the past," rapes, robbcncs, motor vehicle said McCaffrey. "There is no thefL<>, or arrests for alcohol on the difference m how wc'rcrcacting." Carroll campus m the year 1991. Donna Byrnes, d1rector of Three aggravated assaults and 13 housmg, said that the new law has burglaries were reponed. caused the housing office to alter The annual report IS legally slightly its previous proceedmgs. -

Annual Report 2009-2010 PDF 7.6 MB

Report NZ On Air Annual Report for the year ended 30 June 2010 Report 2010 Table of contents He Rarangi Upoko Part 1 Our year No Tenei Tau 2 Highlights Nga Taumata 2 Who we are Ko Matou Noa Enei 4 Chair’s introduction He Kupu Whakataki na te Rangatira 5 Key achievements Nga Tino Hua 6 Television investments: Te Pouaka Whakaata 6 $81 million Innovation 6 Diversity 6 Value for money 8 Radio investments: Te Reo Irirangi 10 $32.8 million Innovation 10 Diversity 10 Value for money 10 Community broadcasting investments: Mahi Whakapaoho a-Iwi 11 $4.3 million Innovation 11 Diversity 11 Value for money 11 Music investments: Te Reo Waiata o Aotearoa 12 $5.5 million Innovation 13 Diversity 14 Value for money 15 Maori broadcasting investments: Mahi Whakapaoho Maori 16 $6.1 million Diversity 16 Digital and archiving investments: Mahi Ipurangi, Mahi Puranga 17 $3.6 million Innovation 17 Value for money 17 Research and consultation Mahi Rangahau 18 Operations Nga Tikanga Whakahaere 19 Governance 19 Management 19 Organisational health and capability 19 Good employer policies 19 Key financial and non financial measures and standards 21 Part 2: Accountability statements He Tauaki Whakahirahira Statement of responsibility 22 Audit report 23 Statement of comprehensive income 24 Statement of financial position 25 Statement of changes in equity 26 Statement of cash flows 27 Notes to the financial statements 28 Statement of service performance 43 Appendices 50 Directory Hei Taki Noa 60 Printed in New Zealand on sustainable paper from Well Managed Forests 1 NZ On Air Annual Report For the year ended 30 June 2010 Part 1 “Lively debate around broadcasting issues continued this year as television in New Zealand marked its 50th birthday and NZ On Air its 21st. -

The Weekly Challenger : 2017 : 10 : 26

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Newspaper collection The Weekly Challenger 2017-10-26 The Weekly Challenger : 2017 : 10 : 26 The Weekly Challenger, et al Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/challenger Recommended Citation The Weekly Challenger, et al, "The Weekly Challenger : 2017 : 10 : 26" (2017). Newspaper collection. 718. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/challenger/718 This is brought to you for free and open access by the The Weekly Challenger at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Newspaper collection by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1967 2017 The Weekly Challenger BLACK MEN MUST SELL AS WELL AS BUY OR ELSE REMAIN A BEGGAR RACE. VOL. 50 NO. 10OCTOBER 26 - NOVEMBER 1, 2017 50¢ IN THIS Open letter from the WEEK mayor PAGE 4 COMMUNITY NEWS The sky has no limits Mayor Rick Kriseman Carla Bristol closed Gallerie 909’s storefront, but the gallery will continue Thank you for engaging, with pop-up exhibits around town. caring about the direction of our city, and for voting in our city’s upcoming municipal election. Your vote is power- Carla is Gallerie 909 ful, for there’s never been more at stake. This election PAGE 7 will decide whether St. Pete COMMUNITY NEWS BY RAVEN JOY SHONEL South America and Bangladesh. there, especially the owner. moves forward and continues A call Staff Writer The gallery livened up the Every time somebody comes in, to makes progress, or turns area, gave black artist an outlet ‘Oh, have you been over to Gal- back to a time of a higher to action ST. -

Copy 38 of Wednesday, June

;~''. :~i 1~j ~M.- rcJ~S ~!\ \\ steJ1D\f\ t:q1 A""- \\. 5'$ Nt /0 -(- 7: \ , • 5petta.i I Pi,1o",,,\ £tAi+,o~ ~OLUME LXXXIX NUMBER 2 PASADENA, CALIFORNIA FRIDAY 2 OCTOBER 19871 What a Wake-Up by Steve Bard The earthquake's epicenter was at Montebello, nine miles away. " I was lying in my bed, half- There were two deaths in the area asleep, dreaming of a place far directly related to the quake. One awav from the first week of class girl was killed at Cal State LA es at Caltech. All was idyllic and when a beam from a parking peaceful. B&G was giving it a miss garage fell on her, and aman was this morning, and unnamed people killed north ofPasadena in the col had stopped bashing about the lapse of a ten-meter deep utility house in a drunken stupor, playing shaft he was servicing. frisbee golf. The damage around Caltech You all know what happened was unexciting, but should give next, unless you're blind, deaf, on Physical Plant something to do in some very heavy sedatives, or have the wee hours for the next few never been to California before and days. There were several gas leaks don't know what it was. The bed around campus, causing barriers to shook. It swayed a foot out of line be set up in Mudd and Spalding to' as if different parts of the floor be closed. Numerous cracks in the couldn't agree on what level they plaster of many buildings are now liked, and were willing to fight to visible, and a few buildings tried get their way. -

Prince of Networks: Bruno Latour and Metaphysics

Open Access Statement – Please Read This book is Open Access. This work is not simply an electronic book; it is the open access version of a work that exists in a number of forms, the traditional printed form being one of them. Copyright Notice This work is ‘Open Access’, published under a creative commons license which means that you are free to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form and that you in no way alter, transform or build on the work outside of its use in normal aca- demic scholarship without express permission of the author and the publisher of this volume. Furthermore, for any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. For more information see the details of the creative commons licence at this website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ This means that you can: • read and store this document free of charge • distribute it for personal use free of charge • print sections of the work for personal use • read or perform parts of the work in a context where no financial transactions take place However, you cannot: • gain financially from the work in anyway • sell the work or seek monies in relation to the distribution of the work • use the work in any commercial activity of any kind • profit a third party indirectly via use or distribution of the work • distribute in or through a commercial body (with the exception of academic usage within educational institutions such as schools and universities) • reproduce, distribute or store the cover image outside of its function as a cover of this work • alter or build on the work outside of normal academic scholarship Cover Art The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions and thus cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. -

BB-1971-12-25-II-Tal

0000000000000000000000000000 000000.00W M0( 4'' .................111111111111 .............1111111111 0 0 o 041111%.* I I www.americanradiohistory.com TOP Cartridge TV ifape FCC Extends Radiation Cartridges Limits Discussion Time (Based on Best Selling LP's) By MILDRED HALL Eke Last Week Week Title, Artist, Label (Dgllcater) (a-Tr. B Cassette Nos.) WASHINGTON-More requests for extension of because some of the home video tuners will utilize time to comment on the government's rulemaking on unused TV channels, and CATV people fear conflict 1 1 THERE'S A RIOT GOIN' ON cartridge tv radiation limits may bring another two- with their own increasing channel capacities, from 12 Sly & the Family Stone, Epic (EA 30986; ET 30986) month delay in comment deadline. Also, the Federal to 20 and more. 2 2 LED ZEPPELIN Communications Commission is considering a spin- Cable TV says the situation is "further complicated Atlantic (Ampex M87208; MS57208) off of the radiated -signal CTV devices for separate by the fact that there is a direct connection to the 3 8 MUSIC consideration. subscriber's TV set from the cable system to other Carole King, Ode (MM) (8T 77013; CS 77013) In response to a request by Dell-Star Corp., which subscribers." Any interference factor would be mul- 4 4 TEASER & THE FIRECAT roposes a "wireless" or "radiated signal" type system, tiplied over a whole network of CATV homes wired Cat Stevens, ABM (8T 4313; CS 4313) the FCC granted an extension to Dec. 17 for com- to a master antenna. was 5 5 AT CARNEGIE HALL ments, and to Dec. -

EV16 Inner DP

16 extreme voice JohnJJohnohn FoxxFoxx Exploring an Ocean of possibilities Extreme Voice 16 : Introduction All text and pictures © Extreme Voice 1997 except where stated. 1 Reproduction by permission only. have please. , g.uk . ears in My Eyes Cerise A. Reed [email protected] , oice Dancing with T obinhar r and eme V Extr hope you’ll like it! The Gift http://www.ultravox.org.uk , e ris, URL: has just been finished, and should be in the shops in June. EMAIL (ROBIN): Monument g.uk Rage In Eden enewal form will be enclosed. Cheques etc payable to (0117) 939 7078 We’ll be aiming for a Christmas issue, though of course this depends on news and events. We’ll Cerise Reed and Robin Har [email protected] UK £7.00 • EUROPE £8.00 • OUTSIDE EUROPE £11.00 as follows: It’s been an exceptionally busy year for us, what with CD re-releases and Internet websites, as you’ll been an exceptionally busy year for us, what with CD re-releases It’s TEL / FAX: THIS YEAR! 19 SALISBURY STREET, ST GEORGE, BRISTOL BS5 8EE ENGLAND STREET, 19 SALISBURY best! ”, and a yellow subscription r y eatment. At the time of writing EV16 EMAIL (CERISE): ry them, or at least be able to order them. So far ry them, or at least be able to order essages to the band, chat with fellow fans, download previously unseen photographs, listen to messages from Midge unseen photographs, listen to messages from essages to the band, chat with fellow fans, download previously ee in the following pages. -

Media – History

Matej Santi, Elias Berner (eds.) Music – Media – History Music and Sound Culture | Volume 44 Matej Santi studied violin and musicology. He obtained his PhD at the University for Music and Performing Arts in Vienna, focusing on central European history and cultural studies. Since 2017, he has been part of the “Telling Sounds Project” as a postdoctoral researcher, investigating the use of music and discourses about music in the media. Elias Berner studied musicology at the University of Vienna and has been resear- cher (pre-doc) for the “Telling Sounds Project” since 2017. For his PhD project, he investigates identity constructions of perpetrators, victims and bystanders through music in films about National Socialism and the Shoah. Matej Santi, Elias Berner (eds.) Music – Media – History Re-Thinking Musicology in an Age of Digital Media The authors acknowledge the financial support by the Open Access Fund of the mdw – University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna for the digital book pu- blication. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche National- bibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http:// dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeri- vatives 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commercial pur- poses, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative of the original work and for commercial use, further permission is required and can be obtained by contacting rights@transcript- publishing.com Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. -

The Spirit of Adventure (Version 0.4)

The Spirit of Adventure (version 0.4) by Michael McCafferty The true story of the summer-long experience of a lifetime: flying a beautiful open-cockpit biplane, with wings of cloth and wood, touring Europe with the freedom of an eagle. © Copyright 2010, all rights reserved Michael McCafferty PO Box 2270 Del Mar, California USA email: [email protected] website: MichaelMcCafferty.com 2 Table of Contents Preface 8 The Fantasies 9 Waiting for the Slow Boat to Paris 12 Day 1: Silent fears 15 Day 2: A Day of Challenges 16 Day 3: A Lesson in French Hospitality 19 Day 4: An Excursion into the Streets of Paris 22 Day 5: The Calm Before The Storm 26 Day 6: Let There Be Wings! 28 Day 7: Taxi Ride from Hell, Haircut in Heaven 30 Day 8: A Very Short Story 33 Day 9: Only Pilots Know Why Birds Sing 34 Day 10: Friday the Thirteenth 37 Day 11: Who Is This Guy? What Makes Him Tick? 40 Day 12: The Paris Air Show 47 Day 13: The Air and Space Museum 51 Day 14: Another Rainy Day in Paris 54 Day 15: An Old Irish Prescription 57 Day 16: Observations From A Sidewalk Café 60 Day 17: The Loose End of a Long Red Tape 65 3 Day 18: Meditations at the Babylon Café 69 Day 19: A Street Party of Epic Proportions 71 Day 20: Anticipation 74 Day 21: Another Day On, and Under, the Ground 77 Day 22: To Fly Is To Be 80 Day 23: Of Corsica! 86 Day 24: More Than Just A Pretty Face 88 Day 25: Mono-kinis 91 Day 26: The Global Perspective 94 Day 27: Please Stand By. -

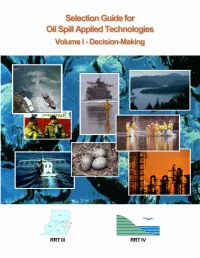

Selection Guide for Oil Spill Applied Technologies: Volume 1

****ATTENTION**** Disclaimer: The information provided in this document by Region III and IV Regional Response Teams is for guidance purposes only. Specific information on countermeasure categories and products used for oil spill response listed in this document does not supersede the National Oil and Hazardous Substances Pollution Contingency Plan (NCP), Subpart J, Product Schedule rule. 40 CFR Part 300.900 addresses specific authorization for use of spill countermeasures. Part 300.905 explains, in detail, the categories and specific requirements of how a product is classified under one of the following categories: dispersants, surface washing agents, bioremediation agents, surface collecting agents, and miscellaneous oil spill control agents. Products that consist of materials that meet the definitions of more than one of the product categories will be listed under one category to be determined by the USEPA. A manufacturer who claims to have more than one defined use for a product must provide data to the USEPA to substantiate such claims. However, it is the discretion of RRTs and OSCs to use the product as appropriate and within a manner consistent with the NCP during a specific spill. For clarification of this disclaimer, or to obtain a copy of a current Product Schedule, please contact the USEPA Oil Program Center at (703) 603-9918. This page intentionally left blank. SSeelleeccttiioonn GGuuiiddee ffoorr OOiill SSppiillll AApppplliieedd TTeecchhnnoollooggiieess VVoolluummee II –– DDeecciissiioonn MMaakkiinngg NOTE: This revision of Volume I of the “Selection Guide for Oil Spill Applied Technologies” reflects many changes from the previous versions. Scientific and Environmental Associates, Incorporated and the Members of the 2002 Selection Guide Development Committee. -

(Ps Fisfffvobiems? Volcano Erupts in Philippines, Kills

hltgriiH i fii SJSjWp'l / jManrlfg0tgr If^ralb MONDAY, DECEMBER -8, IM l Manchester Stores W ill Be Open Until 5:30 P. M, Wednesday Anyone intaraatad ia invited to Bunaat Rebekah Lodga will haa bfcn donated for thia purpo**, amuaament. For tham eapeclally. meet in Odd Fellow* Hall thi* tha Aral project of the ManaAeld aa wall aa for all. television will attend tha aacoad TW C A Homa- Lions Donate ATtrag* Daily Net Press Run 'jUidatTown maker'a Holiday program at the evening. Nomination o f officera Parents Aiuoclation, Dr. Neil A. bring Joy in uktold measura. There Tha Waathar . Community T tomororw morning will taka place and mambara are Dayton, superintendent, stated ia also educational value in TV Fer the Week Ending rsfecaat e( IT. %, WeaOwr Banaa • t U » r g » T t t Itenr'a Mother* from 8:80 to 11 o'clock. From 8:30 reminded to return their cqin To TV Project while expressing hla piaasure and for the echool. For Timeless Beauty December 1 <anl« «Hll hold it* ftnnual Chrlet* to 10 a aoclal hour will be enjoyed cerde. Mre. Rthel Aapinwall. gratitude to the parents and Sixteen television set* are the Meetly eloaiy, not *e eeel to- M * party Wadnewtajr •venin|' at and then for the next hour Mra. noble grand of the lodge, will pro friend* of the Institution for their goal of the aaeoclatlon for Chriat 10,412 algfet. fola feegtuleg bMofe S o'clock ot th« home of Mr*. John Rmily Hou*e Maldment, a former vide entertainment numbera and Cliib (aive» New Mann* enthuaiaam, work and donations. -

Representation of 1980S Cold War Culture and Politics in Popular Music in the West Alex Robbins

University of Portland Pilot Scholars History Undergraduate Publications and History Presentations 12-2017 Time Will Crawl: Representation of 1980s Cold War Culture and Politics in Popular Music in the West Alex Robbins Follow this and additional works at: https://pilotscholars.up.edu/hst_studpubs Part of the European History Commons, Music Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Citation: Pilot Scholars Version (Modified MLA Style) Robbins, Alex, "Time Will Crawl: Representation of 1980s Cold War Culture and Politics in Popular Music in the West" (2017). History Undergraduate Publications and Presentations. 7. https://pilotscholars.up.edu/hst_studpubs/7 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the History at Pilot Scholars. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Undergraduate Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of Pilot Scholars. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Time Will Crawl: Representation of 1980s Cold War Culture and Politics in Popular Music in the West By Alex Robbins Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in History University of Portland December 2017 Robbins 1 The Cold War represented more than a power struggle between East and West and the fear of mutually assured destruction. Not only did people fear the loss of life and limb but the very nature of their existence came into question. While deemed the “cold” war due to the lack of a direct military conflict, battle is not all that constitutes a war. A war of ideas took place. Despite the attempt to eliminate outside influence, both East and West felt the impact of each other’s cultural movements.