Back of Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Advanced Songwriting System for Crafting Songs That People Want to Hear

How to Write Songs That Sell _________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ An Advanced Songwriting System for Crafting Songs That People Want to Hear By Anthony Ceseri This is NOT a free e-book! You have been given one copy to keep on your computer. You may print out one copy only for your use. Printing out more than one copy, or distributing it electronically is prohibited by international and U.S.A. copyright laws and treaties, and would subject the purchaser to expensive penalties. It is illegal to copy, distribute, or create derivative works from this book in whole or in part, or to contribute to the copying, distribution, or creating of derivative works of this book. Furthermore, by reading this book you understand that the information contained within this book is a series of opinions and this book should be used for personal entertainment purposes only. None of what’s presented in this book is to be considered legal or personal advice. Published by: Success For Your Songs Visit us on the web at: http://www.SuccessForYourSongs.com Copyright © 2012 by Success For Your Songs All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. How to Write Songs That Sell 3 Table of Contents Introduction 6 The Methods 8 Special Report 9 Module 1: The Big -

The Apprenticeship of Duddy Kravitz Had Been a Popular Movie, with Richard Dreyfuss Playing a Jewish Nerd

Begin Reading Table of Contents About the Author Photos Copyright Page Thank you for buying this Henry Holt and Company ebook. To receive special offers, bonus content, and info on new releases and other great reads, sign up for our newsletters. Or visit us online at us.macmillan.com/newslettersignup For email updates on Lenny Kravitz, click here. The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy. For my mother I can’t breathe. Beneath the ground, the wooden casket I am trapped in is being lowered deeper and deeper into the cold, dark earth. Fear overtakes me as I fall into a paralytic state. I can hear the dirt being shoveled over me. My heart pounds through my chest. I can’t scream, and if I could, who would hear me? Just as the final shovel of soil is being packed tightly over me, I convulse out of my nightmare into the sweat- and urine-soaked bed in the small apartment on the island of Manhattan that my family calls home. Shaken and disoriented, I make my way out of the tiny back bedroom into the pitch-dark living room, where my mother and father sleep on a convertible couch. I stand at the foot of their bed just staring … waiting. -

Jacknife Lee

Jacknife Lee It is fair to say that Jacknife Lee has become one of the most sought after and highly influential producers currently at work. Lee’s career has encompassed work with some of the biggest and most influential artists on both sides of the Atlantic in the shape of Taylor Swift, U2, R.E.M., Kasabian, Robbie Williams and Neil Diamond. His work on U2’s “How To Dismantle An Atom Bomb” saw him collect two Grammy Awards in 2006 as well as Producer of the Year at the UK MMF Awards. He was also again Grammy nominated in 2013 for his work on Swift’s multi-million selling album “Red.” Currently working on what looks set to be the biggest album from Scottish alt-rock heroes Twin Atlantic and the debut album from The Gossip’s Beth Ditto, Lee has also produced a handful of tracks on Jake Bugg’s upcoming third album and is just about to commence work with Two Door Cinema Club after their successful collaboration on Beacon two years previously. In 2014, Lee was honoured to be asked to co-produce Neil Diamond’s “Melody Road” album alongside the tremendously talented Don Was. “Melody Road” debuted at #3 in America and #4 in the UK as it received universal critical acclaim. Lee has gained much recognition as a writer producer over the last five years. In 2014 also Lee co write and produced various singles for Kodaline’s second album “Coming Up For Air” which peaked at #2, while he also produced and co-wrote Twin Atlantic’s Radio 1 A-listed singles “Heart and Soul” and “Brothers and Sisters.” In addition, Lee spent some of the year writing and producing track for alternative urban artist Raury. -

Deeper Teaching

DEEPER LEARNING RESEARCH SERIES DEEPER TEACHING By Magdalene Lampert December 2015 JOBS FOR THE FUTURE i EDiTORS’ iNTRODUCTiON TO THE DEEPER LEARNiNG RESEARCH SERiES In 2010, Jobs for the Future—with support from the Nellie Mae Education Foundation—launched the Students at the Center initiative, an effort to identify, synthesize, and share research findings on effective approaches to teaching and learning at the high school level. The initiative began by commissioning a series of white papers on key topics in secondary schooling, such as student motivation and engagement, cognitive development, classroom assessment, educational technology, and mathematics and literacy instruction. Together, these reports—collected in the edited volume Anytime, Anywhere: Student-Centered Learning for Schools and Teachers, published by Harvard Education Press in 2013—make a compelling case for what we call “student-centered” practices in the nation’s high schools. Ours is not a prescriptive agenda; we don’t claim that all classrooms must conform to a particular educational model. But we do argue, and the evidence strongly suggests, that most, if not all, students benefit when given ample opportunities to: > Participate in ambitious and rigorous instruction tailored to their individual needs and interests > Advance to the next level, course, or grade based on demonstrations of their skills and content knowledge > Learn outside of the school and the typical school day > Take an active role in defining their own educational pathways Students at the Center will continue to gather the latest research and synthesize key findings related to student engagement and agency, competency education, and other critical topics. Also, we have developed—and have made available at www.studentsatthecenterhub.org—a wealth of free, high-quality tools and resources designed to help educators implement student-centered practices in their classrooms, schools, and districts. -

2014 in Young Voices 2015 Careful—The Publication You’Re Holding Is Precious

magazine of teen writing and visual art TORONTO PUBLIC LIBRARY His Blood Tennesha Skyers, age 19 GET PUBLISHED! Welcome to Young Voices 2014 in Young Voices 2015 Careful—the publication you’re holding is precious. Within its pages are the aspirations, musings, rants, raves, and reveries from teens all across Love what you’re reading here? the city of Toronto, bound in poems, stories, drawings, and photographs. Want to be part of it? Young Voices magazine is an annual publication dedicated to the work of Submit stories, poems, rants, Toronto’s emerging artists. It provides an unbarred canvas for teens ages artwork, photos... 12–19 to showcase their talent, get their voices heard, and experience the Submit NOW! thrill of seeing their work published. See page 67 for details. Every masterpiece you’ll find in here has been selected by a team of teen volunteers and their Toronto-based writer/artist mentors, who pore over hundreds of submissions in order to pick their favourites for publication. It’s never an easy process, and sometimes we simply receive too many amazing works to fit in. But it’s always an incredible journey through the hearts and minds of our city’s teens, and we hope you’ll enjoy exploring this anthology as much as we did compiling it. Hearty congratulations to everyone who got in, and a big thanks to the volunteers of the selection team! The Young Voices 2014 editorial board: Robert Adragna Gary Barwin Michael Brown Karen Krossing Nini Chen Wenting Li Yujia Cheng Geraldynn Lubrido Justine Shackleton Angela Dou Saambavi Mano Shelley She Kristyn Dunnion Camille Martin Atara Shields Benjamin Gabbay Fiona McKendrick Sierra Sun Thamy Giritharan Claire Merner Evi Tampold Carol Hu Leigh Nash Matthew Tierney Ishanee Jahagirdar Anupya Caleb Tseng-Tham Dana Kokoska Pamidimukkala Navkiran Verma FRONT COVER ART Alana Park Annie Vimalanathan Terese Pierre Allen Wang An Ecological Maria Yang Footprint Stephanie Yip Angela Dong, age 14 young voices magazine 2014 CONTENTS Poetry Something Growing, Nuard Tadevosyan, age 19 ............ -

Story)Line: Group Facilitation with Men in Recovery at the Als Vation Army Lisa Pia Zonni Spinazola University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School July 2018 Lives on the (story)Line: Group Facilitation with Men in Recovery at The alS vation Army Lisa Pia Zonni Spinazola University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the Communication Commons Scholar Commons Citation Spinazola, Lisa Pia Zonni, "Lives on the (story)Line: Group Facilitation with Men in Recovery at The alvS ation Army" (2018). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7366 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lives on the (story)Line: Group Facilitation with Men in Recovery at The Salvation Army by Lisa Pia Zonni Spinazola A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Communication College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Co-Major Professor: Carolyn Ellis, Ph.D. Co-Major Professor: Ambar Basu, Ph.D. Arthur Bochner, Ph.D. Donileen Loseke, Ph.D. Date of Approval: June 28, 2018 Keywords: addiction, grief and trauma, emotions, narrative reframing, autoethnography Copyright © 2018, Lisa Pia Zonni Spinazola DEDICATION I dedicate this project first to my children who through their mere existence give me a why to live, and second to my participants and other men at The Salvation Army who grapple with finding a how to live (Frankl, 1984). -

Table of Contents

Theory and Evidence… Satellite Radio: Can It Survive? by Ashley Schutz An honors thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science Undergraduate College Leonard N. Stern School of Business New York University May 2006 Professor Marti G. Subrahmanyam Professor Al Lieberman Faculty Adviser Thesis Advisor Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Background ..................................................................................................................................... 6 The Industry ........................................................................................................................ 6 The Companies ................................................................................................................... 8 Executive Leadership .......................................................................................................... 9 Competitive Environment ............................................................................................................. 10 Satellite Radio Competition .............................................................................................. 10 Terrestrial Radio Competition ......................................................................................... -

The BG News September 18, 2019

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 9-18-2019 The BG News September 18, 2019 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation State University, Bowling Green, "The BG News September 18, 2019" (2019). BG News (Student Newspaper). 9108. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/9108 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. UNITED BY CULTURE bg Student unions offer safe spaces, belonging news An independent student press serving the campus and surrounding community, ESTABLISHED 1920 Bowling Green State University Wednesday, September 18, 2019 Volume 99, Issue 5 BSU ASU QTSU LSU Former Falcon, rockstar dies Twins reflect on volleyball careers 2020 candidates vie for poll leads Page 5 Page 9 Page 11 BG NEWS September 18, 2019 | PAGE 2 Student unions uplift multicultural student inclusion Olivia Metcalfe development,” she said. Reporter Latham mentioned what she wants students to think of when they think of QTSU. Finding a group in which students feel they “It is a place where people, especially those belong remains an integral part of the college in the queer and trans community, can feel experience. Various student unions strive to safe. We are always striving for a loving and create these groups for all students. -

200 March Against War Group Protests U.S

Local music stores Men's basketball~ begin checking ID sinks to 0-5 age 2 age 15 TUESDAY 200 march against war Group protests U.S. policy in Mideast By Kathleen Graham awareness in the community." Student Affairs Editor The group, however, neither Two! Four! Six! Eight! No supports nor condemns the offensive in Kuwait! defensive U.S. military presence in More than 200 people chanted, the Gulf, member Martin Anderson carried signs and marched around (AS 93) said. the Mall Friday afternoon in the "We're not against the soldiers," Citizeos Against War (CAW) Anderson said. protest against U.S. military One student staged a counter aggression in Kuwait. protest along the route. Kevin "We want to get people angry, get O'Neill (AS 91) said he spoke for people worried about what's going other people that are quieter th an on," said CAW member Ellen Cone himself. (AS 94). "If [Saddam] is not out by Jan . The march started at the steps of 15 , then the only other option is Memorial Hall, circled the Mall and military," O'Neill said. ended at the Perkins Student Center, Ed Coburn, who coordinates th e where CAW members and other Delaware outpost of the Vietnam supporters spoke to the crowd. Veterans Against the War/ Anti CAW, which formed in Imperialists, said: "I oppose all sorts November as a response to the of war, especially when youth pay growing threat of war in the Middle for it with zipped-up body bags. East, uow includes about 70 They're just using your body for members. -

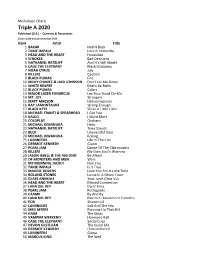

Triple a 2020

Mediabase Charts Triple A 2020 Published (U.S.) -- Currents & Recurrents January 2020 through December, 2020 Rank Artist Title 1 BAKAR Hell N Back 2 TAME IMPALA Lost In Yesterday 3 HEAD AND THE HEART Honeybee 4 STROKES Bad Decisions 5 NATHANIEL RATELIFF And It's Still Alright 6 CAGE THE ELEPHANT Black Madonna 7 NOAH CYRUS July 8 KILLERS Caution 9 BLACK PUMAS Fire 10 MILKY CHANCE & JACK JOHNSON Don't Let Me Down 11 WHITE REAPER Might Be Right 12 BLACK PUMAS Colors 13 MAJOR LAZER F/MARCUS Lay Your Head On Me 14 MT. JOY Strangers 15 MATT MAESON Hallucinogenics 16 RAY LAMONTAGNE Strong Enough 17 BLACK KEYS Shine A Little Light 18 MICHAEL FRANTI & SPEARHEAD I Got You 19 KALEO I Want More 20 COLDPLAY Orphans 21 MICHAEL KIWANUKA Hero 22 NATHANIEL RATELIFF Time Stands 23 BECK Uneventful Days 24 MICHAEL KIWANUKA Rolling 25 LUMINEERS Life In The City 26 DERMOT KENNEDY Giants 27 PEARL JAM Dance Of The Clairvoyants 28 KILLERS My Own Soul's Warning 29 JASON ISBELL & THE 400 UNIT Be Afraid 30 OF MONSTERS AND MEN Wars 31 MY MORNING JACKET Feel You 32 TAME IMPALA Is It True 33 MAGGIE ROGERS Love You For A Long Time 34 ROLLING STONES Living In A Ghost Town 35 GLASS ANIMALS Your Love (Deja Vu) 36 HEAD AND THE HEART Missed Connection 37 LANA DEL REY Doin' Time 38 PEARL JAM Retrograde 39 CAAMP By And By 40 LANA DEL REY Mariners Apartment Complex 41 EOB Shangri-LA 42 LUMINEERS Salt And The Sea 43 MEG MYERS Running Up That Hill 44 HAIM The Steps 45 VAMPIRE WEEKEND Harmony Hall 46 CAGE THE ELEPHANT Social Cues 47 DEVON GILFILLIAN The Good Life 48 DERMOT KENNEDY -

Future Perfect

FUTURE PERFECT PAST IMPERFECT SERIES – BOOK III FLETCHER DELANCEY Copyright © 2005 by Fletcher DeLancey CONTENTS Author’s note v Other books by Fletcher DeLancey vii Prologue 1 Chapter 1 7 Chapter 2 22 Chapter 3 40 Chapter 4 45 Chapter 5 57 Chapter 6 79 Chapter 7 86 Chapter 8 107 Chapter 9 131 Chapter 10 139 Chapter 11 147 Chapter 12 166 Chapter 13 177 Chapter 14 204 Chapter 15 210 Chapter 16 217 EARTH INTERLUDE 226 Chapter 17 231 Chapter 18 243 Chapter 19 256 Chapter 20 276 Chapter 21 293 Chapter 22 298 Chapter 23 325 Chapter 24 328 Chapter 25 352 Chapter 26 361 Chapter 27 368 Chapter 28 381 Chapter 29 392 Chapter 30 410 Chapter 31 422 Chapter 32 428 Chapter 33 443 Chapter 34 473 Chapter 35 483 Further adventures 491 AUTHOR’S NOTE This is the third book in the Past Imperfect series. For more in the series, go to fletcherdelancey.com. The author can be reached via email at fl[email protected] OTHER BOOKS BY FLETCHER DELANCEY Past Imperfect Series Past Imperfect Present Tension Future Perfect No Return Forward Motion Chronicles of Alsea The Caphenon Without A Front: The Producer’s Challenge Without A Front: The Warrior’s Challenge Catalyst Vellmar the Blade (novella) Outcaste To learn about the world of Alsea, immerse yourself in the Chronicles of Alsea site: alseaworld.com For Maria, who taught me that real love need not be limited to fiction. PROLOGUE Alison Necheyev let out a slow breath, resting her head on the back of her seat. -

PUBLIC SUBMISSION Posted: July 16, 2018 Tracking No

As of: 7/16/18 1:07 PM Received: July 06, 2018 Status: Posted PUBLIC SUBMISSION Posted: July 16, 2018 Tracking No. 1k2-944l-u3jz Comments Due: July 09, 2018 Submission Type: Web Docket: BIS-2017-0004 Control of Firearms, Guns, Ammunition and Related Articles the President Determines No Longer Warrant Control Under the United States Munitions List (USML) Comment On: BIS-2017-0004-0001 Control of Firearms, Guns, Ammunition and Related Articles the President Determines No Longer Warrant Control Under the United States Munitions List (USML) Document: BIS-2017-0004-1157 Public comment 386. Individual. Bruce Cole. 7-6-18 Submitter Information Name: Bruce Cole Address: 111 Griffin Ave Hampden, 04444 Email: [email protected] General Comment I wish to object to any regulatory change that increases the health and safety of humans anywhere. Our injury and death statistics related to firearms incidents dwarfs that of the rest of the civilized world. We do not need to export that kind of risk elsewhere. Profiting from this would benefit a very few compared to the potential harm to others. And it is likely some of these weapons could be used on Americans. Please refuse this regulation change. Thank you. As of: 7/16/18 1:06 PM Received: July 06, 2018 Status: Posted PUBLIC SUBMISSION Posted: July 16, 2018 Tracking No. 1k2-944l-9pgp Comments Due: July 09, 2018 Submission Type: Web Docket: BIS-2017-0004 Control of Firearms, Guns, Ammunition and Related Articles the President Determines No Longer Warrant Control Under the United States Munitions List (USML) Comment On: BIS-2017-0004-0001 Control of Firearms, Guns, Ammunition and Related Articles the President Determines No Longer Warrant Control Under the United States Munitions List (USML) Document: BIS-2017-0004-1156 Public comment 387.