Purnululu National Park

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Heritage Grants 2020- 21 Grant Opportunity

Grant Opportunity Guidelines Australian Heritage Grants 2020- 21 Grant Opportunity Opening date: 9 November 2020 Closing date and time: 5.00pm Australian Eastern Daylight Time 7 January 2021 Please take account of time zone differences when submitting your application. Commonwealth policy Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment entity: Administering entity: Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources Enquiries: If you have any questions, contact us on 13 28 46 or [email protected] Date guidelines released: 9 November 2020 Type of grant opportunity: Open competitive Contents 1. Australian Heritage Grants processes...............................................................................4 2. About the grant program ...................................................................................................5 3. Grant amount and grant period .........................................................................................5 3.1. Grants available ......................................................................................................6 3.2. Project period ..........................................................................................................6 4. Eligibility criteria................................................................................................................6 4.1. Who is eligible? .......................................................................................................6 4.2. Additional eligibility requirements ..............................................................................7 -

Cape Range National Park

Cape Range National Park Management Plan No 65 2010 R N V E M E O N G T E O H F T W A E I S L T A E R R N A U S T CAPE RANGE NATIONAL PARK Management Plan 2010 Department of Environment and Conservation Conservation Commission of Western Australia VISION By 2020, the park and the Ningaloo Marine Park will be formally recognised amongst the world’s most valuable conservation and nature based tourism icons. The conservation values of the park will be in better condition than at present. This will have been achieved by reducing stress on ecosystems to promote their natural resilience, and facilitating sustainable visitor use. In particular, those values that are not found or are uncommon elsewhere will have been conserved, and their special conservation significance will be recognised by the local community and visitors. The park will continue to support a wide range of nature-based recreational activities with a focus on preserving the remote and natural character of the region. Visitors will continue to enjoy the park, either as day visitors from Exmouth or by camping in the park itself at one of the high quality camping areas. The local community will identify with the park and the adjacent Ningaloo Marine Park, and recognise that its values are of international significance. An increasing number of community members will support and want to be involved in its ongoing management. The Indigenous heritage of the park will be preserved by the ongoing involvement of the traditional custodians, who will have a critical and active role in jointly managing the cultural and conservation values of the park. -

2017 Conservation Outlook Assessment (Archived)

IUCN World Heritage Outlook: https://worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org/ Purnululu National Park - 2017 Conservation Outlook Assessment (archived) IUCN Conservation Outlook Assessment 2017 (archived) Finalised on 08 November 2017 Please note: this is an archived Conservation Outlook Assessment for Purnululu National Park. To access the most up-to-date Conservation Outlook Assessment for this site, please visit https://www.worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org. Purnululu National Park SITE INFORMATION Country: Australia Inscribed in: 2003 Criteria: (vii) (viii) Site description: The 239,723 ha Purnululu National Park is located in the State of Western Australia. It contains the deeply dissected Bungle Bungle Range composed of Devonian-age quartz sandstone eroded over a period of 20 million years into a series of beehive-shaped towers or cones, whose steeply sloping surfaces are distinctly marked by regular horizontal bands of dark-grey cyanobacterial crust (single-celled photosynthetic organisms). These outstanding examples of cone karst owe their existence and uniqueness to several interacting geological, biological, erosional and climatic phenomena. © UNESCO IUCN World Heritage Outlook: https://worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org/ Purnululu National Park - 2017 Conservation Outlook Assessment (archived) SUMMARY 2017 Conservation Outlook Good Purnululu National Park is a solid example of a site inscribed for landscape and geological outstanding value, but with significant biological importance, both at a regional as well as international scale. Thanks to a low level of threat and good protection and management including the creation of more conservation lands around the property, all values appear to be stable and some are even improving, given that the site was damaged by grazing prior to inscription. While there is always the potential for a catastrophic event such as uncontrolled fire or invasion by alien species, risk management plans are in place although in this case the relatively low level of funding for park management would have to be raised. -

The Future of World Heritage in Australia

Keeping the Outstanding Exceptional: The Future of World Heritage in Australia Editors: Penelope Figgis, Andrea Leverington, Richard Mackay, Andrew Maclean, Peter Valentine Editors: Penelope Figgis, Andrea Leverington, Richard Mackay, Andrew Maclean, Peter Valentine Published by: Australian Committee for IUCN Inc. Copyright: © 2013 Copyright in compilation and published edition: Australian Committee for IUCN Inc. Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: Figgis, P., Leverington, A., Mackay, R., Maclean, A., Valentine, P. (eds). (2012). Keeping the Outstanding Exceptional: The Future of World Heritage in Australia. Australian Committee for IUCN, Sydney. ISBN: 978-0-9871654-2-8 Design/Layout: Pixeldust Design 21 Lilac Tree Court Beechmont, Queensland Australia 4211 Tel: +61 437 360 812 [email protected] Printed by: Finsbury Green Pty Ltd 1A South Road Thebarton, South Australia Australia 5031 Available from: Australian Committee for IUCN P.O Box 528 Sydney 2001 Tel: +61 416 364 722 [email protected] http://www.aciucn.org.au http://www.wettropics.qld.gov.au Cover photo: Two great iconic Australian World Heritage Areas - The Wet Tropics and Great Barrier Reef meet in the Daintree region of North Queensland © Photo: K. Trapnell Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the chapter authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the editors, the Australian Committee for IUCN, the Wet Tropics Management Authority or the Australian Conservation Foundation or those of financial supporter the Commonwealth Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. -

Public Place Names (Harrison) Determination 2006 (No 2)

Australian Capital Territory Public Place Names (Harrison) Determination 2006 (No 2) Disallowable instrument DI2006 -96 made under the Public Place Names Act 1989— section 3 (Minister to determine names) I DETERMINE the names of the public places that are Territory land as specified in the attached schedule and as indicated on the attached plan. Neil Savery Delegate of the Minister 31 May 2006 Page 1 of 8 Authorised by the ACT Parliamentary Counsel—also accessible at www.legislation.act.gov.au SCHEDULE Public Place Names (Harrison) Determination 2006 (No 2) Division of Harrison: Natural Geographical Features of Australia District of Gungahlin: Gungahlin Pioneers NAME ORIGIN SIGNIFICANCE Bungle Bungle Bungle Bungles The Bungle Bungle Range is within the 45 000 Crescent Western Australia hectare Purnululu National Park, in the Kimberley region of north-eastern Western Australia. The Park is 260km south of Kununurra and 110km north of Halls Creek. The Bungle Bungles consists of a group of rounded beehive-shaped domes of horizontally-stratified sandstone and conglomerate which were deposited in the Ord Basin about 375 to 350 million years ago. The range is 578m above sea level, and rises 200 - 300m above the surrounding plain. It covers an area of about 35km by 24km. Combo Waterholes are situated on the Diamantina Combo Court Combo Waterholes River south-east of Kynuna. They are believed to Queensland be the site that inspired Banjo Paterson to write Waltzing Matilda while on a visit to Dagworth Station in 1895. Combo Waterhole Conservation Park contains a string of semi-permanent coolibah-lined lagoons in outback Queensland. -

Australia's National Heritage

AUSTRALIA’S australia’s national heritage © Commonwealth of Australia, 2010 Published by the Australian Government Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts ISBN: 978-1-921733-02-4 Information in this document may be copied for personal use or published for educational purposes, provided that any extracts are fully acknowledged. Heritage Division Australian Government Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts GPO Box 787 Canberra ACT 2601 Australia Email [email protected] Phone 1800 803 772 Images used throughout are © Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts and associated photographers unless otherwise noted. Front cover images courtesy: Botanic Gardens Trust, Joe Shemesh, Brickendon Estate, Stuart Cohen, iStockphoto Back cover: AGAD, GBRMPA, iStockphoto “Our heritage provides an enduring golden thread that binds our diverse past with our life today and the stories of tomorrow.” Anonymous Willandra Lakes Region II AUSTRALIA’S NATIONAL HERITAGE A message from the Minister Welcome to the second edition of Australia’s National Heritage celebrating the 87 special places on Australia’s National Heritage List. Australia’s heritage places are a source of great national pride. Each and every site tells a unique Australian story. These places and stories have laid the foundations of our shared national identity upon which our communities are built. The treasured places and their stories featured throughout this book represent Australia’s remarkably diverse natural environment. Places such as the Glass House Mountains and the picturesque Australian Alps. Other places celebrate Australia’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture—the world’s oldest continuous culture on earth—through places such as the Brewarrina Fish Traps and Mount William Stone Hatchet Quarry. -

Purnululu National Park Australia

PURNULULU NATIONAL PARK AUSTRALIA The Bungle-Bungle Range is a spectacular karst landscape of high cones of quartz-sandstone. It has been deeply dissected into round-topped towers of orange rock banded with dark grey cyanobacterial crusts which change color after rain. With their deep intervening palm lined gorges the landscape is geologically unrivalled and of unusual beauty. The region is between desert and savannah with wildlife and flora of both, and several endemic species. Within it lived one of the few ancient hunter-gatherer aboriginal societies which has retained its vitality. They expressed their ties to the land in the well-known paintings of the Turkey Creek artists. COUNTRY Australia NAME Purnululu National Park NATURAL WORLD HERITAGE SITE 2003: Inscribed on the World Heritage List under Natural Criteria vii and viii. STATEMENT OF OUTSTANDING UNIVERSAL VALUE [pending] The UNESCO World Heritage Committee issued the following statement at the time of inscription: Justification for Inscription Criterion (viii): Earth’s history and geological features. The claim to outstanding universal geological value is made for the Bungle Bungle Range. The Bungle Bungles are, by far, the most outstanding example of cone karst in sandstones anywhere in the world and owe their existence and uniqueness to several interacting geological, biological, erosional and climatic phenomena. The sandstone karst of PNP is of great scientific importance in demonstrating so clearly the process of cone karst formation on sandstone - a phenomenon recognised by geomorphologists only over the past 25 years and still incompletely understood, despite recently renewed interest and research. The Bungle Bungle Ranges of PNP also display to an exceptional degree evidence of geomorphic processes of dissolution, weathering and erosion in the evolution of landforms under a savannah climatic regime within an ancient, stable sedimentary landscape. -

Purnululu National Park World Heritage Area Visitor Guide

World Heritage c k C r e e k In 2003 the national park was World Heritage-listed for two R o e d Purnululu main features – the area’s incredible natural beauty and its R outstanding geological value. National Park The Bungle Bungle Range is renowned for its striking banded domes; the world’s most exceptional example of cone karst Echidna Osmand World Heritage Area formations. They are made of sandstone deposited about 360 Lookout million years ago. Erosion by creeks, rivers and weathering in the Bloodwoods past 20 million years has carved out these domes, along with Lookout spectacular chasms and gorges, creating a surreal landscape. The Bloodwoods Echidna The domes’ striking orange and grey bands are caused by the Chasm presence or absence of cyanobacteria. Dark bands indicate Mini the presence of the cyanobacteria, which grows on layers of Palms sandstone where moisture accumulates. The orange bands are a d Gorge Above Piccaninny Gorge. o Stonehenge R oxidised iron compounds that have dried out too quickly for the e cyanobacteria to grow. g r Homestead Welcome o Valley Wildlife G 14.5 km Local Aboriginal people maintain a strong connection to this ancient landscape; a continual connection and association More than 600 plant species have been recorded in Purnululu expressed through story, song, art and visits. People continue National Park, some of which are unique to the park. Typical tree species include bloodwoods and snappy gums. There are p to use resources that have sustained their lives for thousands o 13 species of spinifex – more than anywhere else in Australia. -

2014 Conservation Outlook Assessment (Archived)

IUCN World Heritage Outlook: https://worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org/ Purnululu National Park - 2014 Conservation Outlook Assessment (archived) IUCN Conservation Outlook Assessment 2014 (archived) Finalised on 15 June 2014 Please note: this is an archived Conservation Outlook Assessment for Purnululu National Park. To access the most up-to-date Conservation Outlook Assessment for this site, please visit https://www.worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org. Purnululu National Park SITE INFORMATION Country: Australia Inscribed in: 2003 Criteria: (vii) (viii) Site description: The 239,723 ha Purnululu National Park is located in the State of Western Australia. It contains the deeply dissected Bungle Bungle Range composed of Devonian-age quartz sandstone eroded over a period of 20 million years into a series of beehive-shaped towers or cones, whose steeply sloping surfaces are distinctly marked by regular horizontal bands of dark-grey cyanobacterial crust (single-celled photosynthetic organisms). These outstanding examples of cone karst owe their existence and uniqueness to several interacting geological, biological, erosional and climatic phenomena. © UNESCO IUCN World Heritage Outlook: https://worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org/ Purnululu National Park - 2014 Conservation Outlook Assessment (archived) SUMMARY 2014 Conservation Outlook Good Purnululu National Park is a solid example of a site inscribed for landscape and geological outstanding value, but with significant biological importance, both at a regional as well as international scale. Thanks to a low level of threat and good protection and management including the creation of more conservation lands around the property, all values appear to be stable and some are even improving, given that the site was damaged by grazing prior to inscription. While there is always the potential for a catastrophic event such as uncontrolled fire or invasion by alien species, risk management plans are in place although in this case the relatively low level of funding for park management would have to be raised. -

Steps for Sustainable Tourism

Steps for Sustainable Tourism Purnululu National Park East Kimberley, Western Australia Final overview report Kim Bridge with Nicholas Hall June 2005 Steps for Sustainable Tourism – Purnululu 2005 © Commonwealth of Australia 2004 This work is copyright. Information presented in this document may be reproduced in whole or in part for study and training purposes, subject to the inclusion of acknowledgement of source and provided no commercial usage or sale occurs. Reproduction for purposes other than those given above, and any uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, requires prior written permission from the Commonwealth, available from the Department of the Environment and Heritage. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to: Assistant Secretary Heritage Division Department of the Environment and Heritage GPO Box 787 CANBERRA ACT 2601 [email protected] The views and opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Australian Government or the Minister for the Environment and Heritage. While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Australian Government does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. Steps tp Sustainable Tourism was developed by the Heritage and Tourism Section of the Australian Government Department of the Environment and Heritage. The publication was designed by Allison Mortlock, Angel Ink. Photographs and images 1. -

Report Nnual

DEPARTMENT OF CONSERVATION AND LAND MANAGEMENT nnual eport A R 2002-2003 HIGHLIGHTS OF THE YEAR Our Vision Our Principles Our Responsibilities A natural environment In making decisions we will be guided The Department of Conservation and in Western Australia that by the following principles: Land Management is part of a greater retains its biodiversity and • The diversity and health of ecological conservation community and has enriches people’s lives. communities and native species distinct State Government throughout WA will be maintained responsibilities for implementing and restored. Government policy within that • Where there are threats of serious or community. Conservation is a irreversible damage, the lack of full collective role. scientific certainty shall not be used Our Mission as a reason for postponing measures We have the lead responsibility for which seek to prevent loss of conserving the State’s rich diversity of In partnership with the community, biodiversity. native plants, animals and natural we conserve Western Australia’s • Users of the environment and ecosystems, and many of its unique biodiversity, and manage the lands resources will pay fair value for that landscapes. On behalf of the people of use. and waters entrusted to us, for their Western Australia, we manage more • Use of wildlife will be on the basis of than 24 million hectares, including intrinsic values and for the ecological sustainability. more than 9 per cent of WA’s land area: appreciation and benefit of present • Outcomes will be delivered in the most its national parks, marine parks, and future generations. effective and efficient way. conservation parks, regional parks, • Cooperation, sharing and integration State forests and timber reserves, of resources and knowledge within the nature reserves, and marine nature Department and between reserves. -

06 Ri 1- Lf O

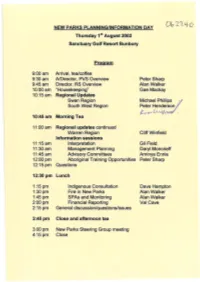

ri 1-_Lf NEW PARKS PLANNING/INFORMATION DAY 06 o Thursday 1st August 2002 Sanctuary Golf Resort Sunbury Program 9:00 am Arrival, tea/coffee 9:30 am A/Director, PVS Overview Peter Sharp 9:45 am Director, RS Overview Alan Walker 10:00 am "Housekeeping" Gae Mackay 10:15 am Regional Updates Swan Region Michael Phillip:Y South West Region Peter Henderson t,., H"-J.N; tjiO ' · 10:45 am Morning Tea 11:00 am Regional updates continued Warren Region Cliff Winfield Information sessions 11:15 am Interpretation Gil Field 11:30 am Management Planning Daryl Moncrieff 11:45 am Advisory Committees Aminya Ennis 12:00 pm Aboriginal Training Opportunities Peter Sharp 12:15 pm Questions 12:30 pm Lunch 1:15 pm Indigenous Consultation Dave Hampton 1:30 pm Fire in New Parks Alan Walker 1:45 pm SPAs and Monitoring Alan Walker 2:00 pm Financial Reporting Val Cave 2:15 pm General discussion/questions/issues 2:45 pm Close and afternoon tea 3:00 pm New Parks Steering Group meeting 4:15 pm Close NEW PARKS BACKGROUND INFORMATION • New Parks Progress Report (produced on a monthly basis, for reporting to Cabinet Sub-committee} • Protecting our old growth forests policy summary: {ALP POOGF Policy): DCLM's achievements/progress to date • New Parks capital and recurrent funding 2002/03 summary • New Parks Steering Group: Terms of Reference vrc;..~\- NEW PARKS PROGRESS REPORT (Protecting our old growth forests policy) June 2002 (2001/02 Summary) The conclusion of the 2001/02 financial year has seen the development of additional, and improvement to existing, visitor facilities in and around more than half of the proposed new national parks in the southwest.