Mike Darwin – Grasping the Nettle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cryonics Magazine, Q1 1999

Mark Your Calendars Today! BioStasis 2000 June of the Year 2000 ave you ever considered Asilomar Conference Center Hwriting for publication? If not, let me warn you that it Northern California can be a masochistic pursuit. The simultaneous advent of the word processor and the onset of the Initial List Post-Literate Era have flooded every market with manuscripts, of Speakers: while severely diluting the aver- age quality of work. Most editors can’t keep up with the tsunami of amateurish submissions washing Eric Drexler, over their desks every day. They don’t have time to strain out the Ph.D. writers with potential, offer them personal advice, and help them to Ralph Merkle, develop their talents. The typical response is to search for familiar Ph.D. names and check cover letters for impressive credits, but shove ev- Robert Newport, ery other manuscript right back into its accompanying SASE. M.D. Despite these depressing ob- servations, please don’t give up hope! There are still venues where Watch the Alcor Phoenix as the beginning writer can go for details unfold! editorial attention and reader rec- Artwork by Tim Hubley ognition. Look to the small press — it won’t catapult you to the wealth and celebrity you wish, but it will give you a reason to practice, and it may even intro- duce you to an editor who will chat about your submissions. Where do you find this “small press?” The latest edition of Writ- ers’ Market will give you several possibilities, but let me suggest a more obvious and immediate place to start sending your work: Cryonics Magazine! 2 Cryonics • 1st Qtr, 1999 Letters to the Editor RE: “Hamburger Helpers” by Charles Platt, in his/her interest to go this route if the “Cryonics” magazine, 4th Quarter greater cost of insurance is more than offset Sincerely, 1998 by lower dues. -

Great Mambo Chicken and the Transhuman Condition

Tf Freewheel simply a tour « // o é Z oon" ‘ , c AUS Figas - 3 8 tion = ~ Conds : 8O man | S. | —§R Transhu : QO the Great Mambo Chicken and the Transhuman Condition Science Slightly Over the Edge ED REGIS A VV Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc. - Reading, Massachusetts Menlo Park, California New York Don Mills, Ontario Wokingham, England Amsterdam Bonn Sydney Singapore Tokyo Madrid San Juan Paris Seoul Milan Mexico City Taipei Acknowledgmentof permissions granted to reprint previously published material appears on page 301. Manyofthe designations used by manufacturers andsellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book and Addison-Wesley was aware of a trademark claim, the designations have been printed in initial capital letters (e.g., Silly Putty). .Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Regis, Edward, 1944— Great mambo chicken and the transhuman condition : science slightly over the edge / Ed Regis. p- cm. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-201-09258-1 ISBN 0-201-56751-2 (pbk.) 1. Science—Miscellanea. 2. Engineering—Miscellanea. 3. Forecasting—Miscellanea. I. Title. Q173.R44 1990 500—dc20 90-382 CIP Copyright © 1990 by Ed Regis All rights reserved. No part ofthis publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Text design by Joyce C. Weston Set in 11-point Galliard by DEKR Corporation, Woburn, MA - 12345678 9-MW-9594939291 Second printing, October 1990 First paperback printing, August 1991 For William Patrick Contents The Mania.. -

The Hostile Spouse Is Almost Exclusively a Female Phenomenon

A Literal Death Sentence One unpleasant issue in cryonics is the "hostile wife" phenomenon. The authors of this article know of a number of high profile cryonicists who need to hide their cryonics activities from their wives and ex-high profile cryonicists who had to choose between cryonics and their relationship. We also know of men who would like to make cryonics arrangements but have not been able to do so because of resistance from their wives or girlfriends. In such cases, the female partner can be described as nothing less than hostile toward cryonics. As a result, these men face certain death as a consequence of their partner's hostility. While it is not unusual for any two people to have differing points of view regarding cryonics, men are more interested in making cryonics arrangements. A recent membership update from the Alcor Life Extension Foundation reports that 667 males and 198 females have made cryonics arrangements. Although no formal data are available, it is common knowledge that a substantial number of these female cryonicists signed up after being persuaded by their husbands or boyfriends. For whatever reason, males are more interested in cryonics than females. These issues raise an obvious question: are women more hostile to cryonics than men? There is no direct answer to this question since the requisite data have not been collected. However, both the gravity and magnitude of the problem, as we are about to detail, suggests this as a fertile, if not urgent, area for future research. One consequence of men being more interested in cryonics than women is that heterosexual men are more often faced with hostile wives and girlfriends than the other way round. -

Curtis Henderson Page 3

3rd Quarter 2009 • Volume 30:3 Cover Story Impressions of Curtis Henderson page 3 Curtis Henderson: Cryonics Pioneer Member Profile: John Schloendorn page 12 page 16 Curtis Henderson [1926 - 2009 - ...] ISSN 1054-4305 $9.95 Improve Your Odds of a Good Cryopreservation You have your cryonics funding and contracts in place but have you considered other steps you can take to prevent problems down the road? þ Do you keep Alcor up-to-date about personal and medical changes? þ Does your Alcor paperwork still reflect your current wishes? þ Have you executed a cryonics-friendly Living Will and Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care? þ Do you wear your bracelet and talk to your friends and family about your desire to be cryopreserved? þ Do you have hostile relatives or supportive relatives that are willing to sign a Relative’s Affidavit? þ Do you attend local cryonics meetings or are you interested in starting a local group yourself? þ Are you interested in contributing to Alcor? Contact Alcor at 1-877-462-5267 and let us know how we can assist you. Take a look at the Alcor Blog www.alcornews.org/weblog Your source for news about: Cryonics technology Cryopreservation cases Television programs about cryonics Speaking events and meetings Employment opportunities 3RD QUARTER 2009 • V OLUME 30:3 e 30:3 Volum 2009 • arter 3rd Qu y Stor over s Contents C ssion mpre I rtis f Cu n o erso Hend : ofile age 3 r Pr p mbe dorn Me loen Sch e 16 rtis : John CpagOVER STORY: PAGE 3 Cu rson nde eer He Pion 16 Member Profile: nics Cryo 12 page Alcor staff member and John Schloendorn icsryonics historian Mike Meet John Schloendorn, Curt rPseorrny remembers Curtis ende Alcor member and H - ...] 200H9 enderson and his [1926 - upcoming young anti- important role in the aging researcher. -

Case Report: Edward W

CryoTransport Case Report: Edward W. Kuhrt, Patient A-1110 by Linda Chamberlain, CryoTransport Manager Alcor Life Extension Foundation Author’s Notes he format used in this report follows closely that used by Mike Darwin of BioPreservation, Inc. This, and Tthe brevity used to describe events during the washout and cryoperfusion, was done in order to make it easier for those who will be using these technical reports in efforts to improve CryoTransport (both transport and preservation) protocols. This technical report was sent out for review and comment prior to publication. Special thanks is given to Hugh Hixon of Alcor and to Mike Darwin of BioPreservation, Inc. for comments and suggestions which improved both the form and substance of this report. CryoTransport can be broken down into three major areas: (1) Remote rescue and transport to Alcor, which includes patient acquisition and stabilization, (2) Cryoprotective Perfusion, and (3) Cooldown and Long-Term Care. This report covers all areas except long-term care, which is just beginning. Background History progress of his disease, however, al- and Synopsis lowed two members of Alcor’s Mr. Kuhrt was one of the earli- CryoTransport Team (Linda Cham- est members of a cryonics organiza- berlain and Tanya Jones) to visit tion. In a LifePact interview made Long Island several weeks in ad- in the hospital several weeks before vance of his cardiopulmonary arrest his cardiopulmonary arrest, Mr. in order to make arrangements with Kuhrt told me many interesting sto- his oncologist, the hospital, and a ries about his early involvement with cooperating funeral home. cryonics. In the mid 1970’s, news- The oncologist and Mather Me- papers ran an article about the morial Hospital in Port Jefferson, Cryonics Society of New York and Long Island, were very supportive about how cryonics was being and gave Alcor unprecedented as- funded by life insurance. -

Member Profile: Mike O’Neal Page 9

May – June 2017 • Volume 38:3 Member Profile: Mike O’Neal Page 9 Interview with Aschwin de Wolf ISSN 1054-4305 Page 14 Case Report: James Baglivo $9.95 Page 22 Improve Your Odds of a Good Cryopreservation You have your cryonics funding and contracts in place but have you considered other steps you can take to prevent problems down the road? ü Keep Alcor up-to-date about personal and medical changes. ü Update your Alcor paperwork to reflect your current wishes. ü Execute a cryonics-friendly Living Will and Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care. ü Wear your bracelet and talk to your friends and family about your desire to be cryopreserved. ü Ask your relatives to sign Affidavits stating that they will not interfere with your cryopreservation. ü Attend local cryonics meetings or start a local group yourself. ü Contribute to Alcor’s operations and research. Contact Alcor (1-877-462-5267) and let us know how we can assist you. Visit the ALCOR FORUMS www.alcor.org/forums/ Discuss Alcor and cryonics topics with other members and Alcor officials. • The Alcor Foundation • Financial • Cell Repair Technologies • Rejuvenation • Cryobiology • Stabilization • Events and Meetings Other features include pseudonyms (pending verification of membership status) and a private forum. Visit the ALCOR BLOG www.alcor.org/blog/ Your source for news about: • Cryonics technology • Speaking events and meetings • Cryopreservation cases • Employment opportunities • Television programs about cryonics Alcor is on Facebook Connect with Alcor members and supporters on our official Facebook page: www.facebook.com/alcor.life.extension.foundation Become a fan and encourage interested friends, family members, and colleagues to support us too. -

Cryonic Preservation of Human Bodies-A Call for Legislative Action

Volume 98 Issue 4 Dickinson Law Review - Volume 98, 1993-1994 6-1-1994 Cryonic Preservation of Human Bodies-A Call For Legislative Action David M. Baker Follow this and additional works at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra Recommended Citation David M. Baker, Cryonic Preservation of Human Bodies-A Call For Legislative Action, 98 DICK. L. REV. 677 (1994). Available at: https://ideas.dickinsonlaw.psu.edu/dlra/vol98/iss4/5 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Dickinson Law IDEAS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dickinson Law Review by an authorized editor of Dickinson Law IDEAS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Cryonic Preservation of Human Bodies - A Call For Legislative Action I. Introduction Cryonics is the practice of freezing, at extremely low temperatures, the body or head of a person who has just legally died in order to preserve it for possible resuscitation at a future time when physical repair and treatment are available.' Cryonics is an offshoot of cryogenics2 and cryobiology, 3 which are two accepted scientific fields. Many scientists in these fields, however, view cryonics as little more than science fiction, despite significant scientific research and theory supporting the hypotheses behind cryonics. 4 The question of whether cryonics is the practice of an experimental science5 or the practice of a cultist fad6 is of no import to the point of this Comment, which is concerned with the lack of any public oversight of the practice of cryonics.7 This is an especially poignant point as the number of people becoming interested in and practicing cryonics is growing each year due to media attention and technological advances." In addition, cryonics is not merely a fad that is soon to fade: cryonics has been practiced for over 25 years;9 the field is more financially 1. -

4Th Quarter 2008 Issue of Cryonics Magazine

4th Quarter 2008 • Volume 29:4 Alcor Supports Molecular Nanotechnology Research and Development page 3 A Cryopreservation Revival Scenario using mNT page 7 interview with Robert Freitas anD Ralph Merkle page 9 Member Profile: ISSN 1054-4305 Kumar Krishnamsetty page 12 $9.95 ALCOR SCIENTIFIC ADVISORY BOARD MEETING By Ralph C. Merkle, Chairman, Alcor Scientific Advisory Board The Alcor Scientific Advisory Board (SAB) met on December 9th and 10th, 2008 in Melbourne, Florida. he first day was devoted to how the cryonics community could Endorsement of Molecular Nanotechnology Research and Development (see the Thelp speed the development of MNT (molecular nanotech- full text in the box below). The full Alcor Board endorsed the state- nology), and how MNT could enable repair of cryopreserved patients. ment at their next regular meeting. We plan to seek broader support Ralph Merkle and Robert Freitas gave a 90 slide Power Point for this statement. presentation about their plan to develop MNT. Further information We’d like to thank all the attendees for making it a stimulating and about their work is available at The Nanofactory Collaboration web- productive meeting. We’d like to offer our particular thanks to Martine site – see http://www.MolecularAssembler.com/Nanofactory, which Rothblatt, whose generous support made the meeting possible. provides an overview of the issues involved in developing nanofacto- The first day SAB attendees were: Antonei Csoka, Aubrey de ries. Grey, Robert Freitas, James Lewis, Ralph Merkle, Marvin Minsky, and Part of their presentation discussed a specific set of nine molec- Martine Rothblatt. Non SAB attendees were Gloria Rudisch (Marvin’s ular tools composed of hydrogen, carbon, and germanium. -

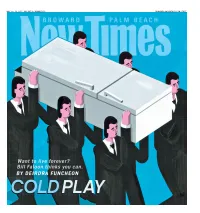

MAY 14 – 20, 2015 | VOLUME 18 | NUMBER 29 BROWARDPALMBEACH.COM I FREE NBROWARD PALM BEACH ® BROWARDPALMBEACH.COM ▼ Contents 2450 HOLLYWOOD BLVD., STE

MAY 14 – 20, 2015 | VOLUME 18 | NUMBER 29 BROWARDPALMBEACH.COM I FREE NBROWARD PALM BEACH ® BROWARDPALMBEACH.COM ▼ Contents 2450 HOLLYWOOD BLVD., STE. 301A HOLLYWOOD, FL 33020 [email protected] 954-342-7700 VOL. 18 | NO. 29 | MAY 14-20, 2015 EDITORIAL EDITOR Chuck Strouse MANAGING EDITOR Deirdra Funcheon EDITORIAL OPERATIONS MANAGER Keith Hollar browardpalmbeach.com STAFF WRITERS Laine Doss, Ray Downs, Chris Joseph, Kyle Swenson browardpalmbeach.com MUSIC EDITOR Ryan Pfeffer ARTS & CULTURE/FOOD EDITOR Rebecca McBane CLUBS EDITOR Laurie Charles PROOFREADER Mary Louise English CONTRIBUTORS David Bader, Nicole Danna, Steve Ellman, Doug Fairall, Chrissie Ferguson, Abel Folgar, Falyn Freyman, Victor Gonzalez, Regina Kaza, Dana Krangel, Erica K. Landau, Matt Preira, Alex Rendon, Andrea Richard, Stephanie Rodriguez, Gillian Speiser, John Thomason, Tana Velen, Sara Ventiera, Lee Zimmerman ART ART DIRECTOR Miche Ratto | CONTENTS | | CONTENTS ASSISTANT ART DIRECTOR Kristin Bjornsen PRODUCTION PRODUCTION MANAGER Mike Lugo PRODUCTION ASSISTANT MANAGER Jorge Sesin ADVERTISING ART DIRECTOR Andrea Cruz PRODUCTION ARTIST Michael Campina ADVERTISING ADVERTISING DIRECTOR Alexis Guillen EWS | PULP EWS MARKETING DIRECTOR Morgan Stockmayer N EVENT MARKETING MANAGER CarlaChristina Thompson DIGITAL MARKETING MANAGER Nathalie Batista ONLINE SUPPORT MANAGER Ryan Garcia Y | RETAIL COORDINATOR Carolina del Busto Sarah Abrahams, Ryan Pete by Illustration DA SENIOR ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES Peter Heumann, Kristi Kinard-Dunstan, Andrea Stern ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES Michelle Beckman, Joanna Brown, Jasmany Santana Featured Stories ▼ CLASSIFIED SENIOR ACCOUNT EXECUTIVES Patrick Butters, Ladyane Lopez, Joel Valez-Stokes ACCOUNT EXECUTIVE Tony Lopez Cold Play GE | NIGHT+ Want to live forever? CIRCULATION A T CIRCULATION DIRECTOR Richard Lynch Bill Faloon thinks you can. S CIRCULATION ASSISTANT MANAGER Rene Garcia BUSINESS BY DEIRDRA FUNCHEON | PAGE 7 GENERAL MANAGER Russell A. -

Ÿþc R Y O N I C S M a G a Z I N E , F E B R U a R Y 2 0

A Non-Profit Organization February 2014 • Volume 35:2 Has Cryonics Taken the Wrong Path? Page 22 Forever Lost? The First Cryonics Brain Repair Paper Page 5 The Case for Whole Body Cryopreservation Page 16 ISSN 1054-4305 $9.95 Improve Your Oddsof a Good Cryopreservation You have your cryonics funding and contracts in place but have you considered other steps you can take to prevent problems down the road? ü Keep Alcor up-to-date about personal and medical changes. ü Update your Alcor paperwork to reflect your current wishes. ü Execute a cryonics-friendly Living Will and Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care. ü Wear your bracelet and talk to your friends and family about your desire to be cryopreserved. ü Ask your relatives to sign Affidavits stating that they will not interfere with your cryopreservation. ü Attend local cryonics meetings or start a local group yourself. ü Contribute to Alcor’s operations and research. Contact Alcor (1-877-462-5267) and let us know how we can assist you. Visit the ALCOR FORUMS www.alcor.org/forums/ Discuss Alcor and cryonics topics with other members and Alcor officials. • The Alcor Foundation • Financial • Cell Repair Technologies • Rejuvenation • Cryobiology • Stabilization • Events and Meetings Other features include pseudonyms (pending verification of membership status) and a private forum. Visit the ALCOR BLOG www.alcor.org/blog/ Your source for news about: • Cryonics technology • Speaking events and meetings • Cryopreservation cases • Employment opportunities • Television programs about cryonics Alcor is on Facebook Connect with Alcor members and supporters on our official Facebook page: www.facebook.com/alcor.life.extension.foundation Become a fan and encourage interested friends, family members, and colleagues to support us too. -

In This Issue ... Plus: Chiller

• ICS Volume 14(9) • September, 1993 ISSN 1054-4305 • $3.50 In This Issue ... Technical Estimates of Success in Cryonics by Ralph Merkle, Ph.D. -And- Deathist Bias in Popular Culture by Steve Neal Plus: Steve Harris,. M.D., reviews Chiller the fascinating new cryonics-based novel by Sterling Blake Cryonics is ...... Alcor is ...... Cryonic suspension is the application of low-temperature The Alcor Life Extension Foundation is a non-profit tax preservation technology to today's terminal patients. The exempt scientific and educational organization. Alcor goal of cryonic suspension and the technology of cryonics is currently has 27 members in cryonic suspension, hundreds the transport of today's terminal patients to a time in the of Suspension Members-people who have arrangements to future when cell/tissue repair technology is available, and be suspended-and hundreds more in the process of becom restoration to full function and health is possible--a time ing Suspension Members. Our -Emergency Response when freezing damage is a fully reversible injury and cures capability includes equipment and trained technicians in exist for virtually all of today's diseases, including aging. New York, Canada, Indiana, North California, and As human knowledge and medical technology continue to England, and a cool-down and perfusion facility in Florida. expand in scope, people who would incorrectly be The Alcor facility, located in Southern California, considered dead by today's medicine will commonly be includes a full-time staff with employees present 24 hours a restored to life and health. This coming control over living day. The facility also has a fully equipped and operational systems should allow us to fabricate new organisms and research laboratory, an ambulance for local response, an sub-cell-sized devices for repair and resuscitation of patients operating room, and a patient storage facility consisting of waiting in cryonic suspension. -

12. Liquid Ventilation

Human Cryopreservation Procedures de Wolf and Platt 12. Liquid Ventilation Introduction We use the term “liquid ventilation” here to describe multiple rapid infusions of the lungs with a breathable liquid capable of introducing oxygen and removing carbon dioxide. In cryonics applications, the liquid will be chilled for the purpose of rapidly cooling a patient. Although boluses of cold perfluorocarbon liquid have been delivered to the lungs of at least one cryonics patient,[1] liquid ventilation by our definition has not been employed in a cryonics case at the time of writing. However, the procedure has been extensively tested in animal studies which initially achieved peak cooling rates of 0.5 degrees Celsius per minute[2] and later 1.0 to 1.3 degrees Celsius per minute (see Figures 12-1 and 12-2). These studies suggest that liquid ventilation has the capability to achieve cooling after cardiac arrest at several times the rate attainable by immersion in ice and water alone, and may cool the body more rapidly than any procedure other than extracorporeal bypass (ECB)[3] while being minimally invasive and appropriate for field deployment. Revision 10-Nov-2019 Copyright by Aschwin de Wolf and Charles Platt Page 12 - 1 Human Cryopreservation Procedures de Wolf and Platt Figure 12-1. Cooling curves from experiments with liquid ventilation devices. These curves were submitted with an international patent application in 2008. A peak cooling rate of greater than 1 degree Celsius was achieved repeatedly, and even at the lower temperature range of 9 to 11 degrees below normal body temperature, the lowest of the curves shows that a rate of approximately 2 degrees in 5 minutes was recorded (0.4 degrees per minute).