ESID Working Paper No. 127 Dominating Dhaka David Jackman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armed Forces War Course-2013 the Ministers the Hon’Ble Ministers Presented Their Vision

National Defence College, Bangladesh PRODEEP 2013 A PICTORIAL YEAR BOOK NATIONAL DEFENCE COLLEGE MIRPUR CANTONMENT, DHAKA, BANGLADESH Editorial Board of Prodeep Governing Body Meeting Lt Gen Akbar Chief Patron 2 3 Col Shahnoor Lt Col Munir Editor in Chief Associate Editor Maj Mukim Lt Cdr Mahbuba CSO-3 Nazrul Assistant Editor Assistant Editor Assistant Editor Family Photo: Faculty Members-NDC Family Photo: Faculty Members-AFWC Lt Gen Mollah Fazle Akbar Brig Gen Muhammad Shams-ul Huda Commandant CI, AFWC Wg Maj Gen A K M Abdur Rahman R Adm Muhammad Anwarul Islam Col (Now Brig Gen) F M Zahid Hussain Col (Now Brig Gen) Abu Sayed Mohammad Ali 4 SDS (Army) - 1 SDS (Navy) DS (Army) - 1 DS (Army) - 2 5 AVM M Sanaul Huq Brig Gen Mesbah Ul Alam Chowdhury Capt Syed Misbah Uddin Ahmed Gp Capt Javed Tanveer Khan SDS (Air) SDS (Army) -2 (Now CI, AFWC Wg) DS (Navy) DS (Air) Jt Secy (Now Addl Secy) A F M Nurus Safa Chowdhury DG Saquib Ali Lt Col (Now Col) Md Faizur Rahman SDS (Civil) SDS (FA) DS (Army) - 3 Family Photo: Course Members - NDC 2013 Brig Gen Md Zafar Ullah Khan Brig Gen Md Ahsanul Huq Miah Brig Gen Md Shahidul Islam Brig Gen Md Shamsur Rahman Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Brig Gen Md Abdur Razzaque Brig Gen S M Farhad Brig Gen Md Tanveer Iqbal Brig Gen Md Nurul Momen Khan 6 Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army 7 Brig Gen Ataul Hakim Sarwar Hasan Brig Gen Md Faruque-Ul-Haque Brig Gen Shah Sagirul Islam Brig Gen Shameem Ahmed Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh Army Bangladesh -

Developments

Highlights: Camp Conditions: • UN agencies will visit Bhasan Char to conduct a technical study of Bhasan Char, which will evaluate its ‘technical, security, and financial’ feasibility to serve as an additional locale for Rohingyas. The plan to move some Rohingya to the island has been delayed until after the Government of Bangladesh gets the “green light” from the UN. High-level Statements: • USAID officials have condemned Myanmar’s inaction in creating conditions conducive to a voluntary, safe and dignified return of the Rohingya. • India has made multiple statements about Rohingya repatriation today, through its Foreign Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, who wrote a letter to the Foreign Minister of Bangladesh, and through Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who had a bilateral meeting with Myanmar State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi on the margins of ASEAN summit in Bangkok. International Events: • At the end of Asean’s biannual summit last week, Asean’s 10 member countries unanimously supported the formation of an ad hoc support team to carry out the recommendations of preliminary needs. That includes continued communication and consultation with affected communities, such as the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh. Country Visits: • USAID deputy administrator Bonnie Glick and acting assistant secretary of State Alice G. Wells visited Bangladesh November 5-7. In a statement following a visit by two top US officials to Bangladesh, the country also underscored that it would continue its efforts to bring an end to the refugee crisis. Developments: A dozen dead, fishermen missing after cyclone Bulbul lashes Bangladesh and India Reuters (November 10) At least 13 people were killed in Bangladesh and India after cyclone Bulbul lashed coastal areas this weekend, though prompt evacuations saved many lives and the worst is over. -

Overseas Study Tour - ND Course 2019 the Three Weeks Overseas Study Tour Include Visit to Neighbouring, Developing and Developed Countries

National Defence College, Bangladesh NDC Newsletter Overseas Study Tour - ND Course 2019 The three weeks overseas study tour include visit to neighbouring, developing and developed countries. The aim of these tours is to examine the social, political, economic and military systems of those countries. The course members September-2019 meet high-ranking civil and military officials and visit government, military Volume-7, Issue-3 and industrial establishments to exchange views and opinions. The visits also promotes good relation between those countries and Bangladesh. This year Course Members of National Defence Course 2019 along with Faculty and Staff Officers visited 15 countries in five groups. Group - 1 visited India, Oman and Russia; Group - 2 visited Nepal, Kuwait and United Kingdom; Group - 3 visited The Editorial Board Thailand, Philippines and Australia; Group - 4 visited Vietnam, Turkey and Italy Chief Patron and Group - 5 visited Bhutan, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and Switzerland. Lt Gen Sheikh Mamun Khaled SUP, rcds, psc, PhD Commandant, NDC Editor Lt Col Nizam Uddin Ahmed afwc, psc, Engr Acting Director (Research and Academic) Associate Editor Lt Col Muhammad Alamgir Iqbal Khan, psc, Arty Senior Research Fellow Assistant Editor Md Nazrul Islam Assistant Director ND Course-2019 visiting delegation (Group-4) at Vietnam during Overseas Study Tour. HIGHLIGHTS OF NDC ND Course-2019 04 July 2019: Lieutenant General Mohammad Overseas Study Tour (OST) Mahfuzur Rahman, OSP, rcds, ndc, afwc, psc, PhD, Principal Staff Officer, Armed Forces Division 19 July 2019-24 July 2019: Overseas Study Tour (OST)-1 04 August 2019: Lieutenant General Sheikh Mamun Khaled, SUP, rcds, psc, PhD, Commandant, NDC 08 September 2019-21 September 2019: Overseas Study Tour (OST)-2 LoCaL Visit-aFWC 2019 GUEst SPEAKERS 03 July 2019: Visit to Police Headquarters 11 July 2019: Dr. -

South Asian Fellowship of Golfing Rotarians (Safgr)

Theme DHAKA HOTELS Orchard Suites: USD.60.00 Net Single Deluxe / USD.80.00 Net Premium Twin – South Asian Rotary Fellowship. Extend our hands through gol ing & be per day. Incl. Breakfast & Airport Transfers. Book with JannatulFerdous Email: inspired. [email protected] Ref: Gol ing Rotarians. � 1ST EDITION ROTARY Asia Paci ic: USD 48.00++ Deluxe Single� / USD. 60.00++ Deluxe Twin – per KGC SOUTH ASIAN FELLOWSHIP day. Incl Breakfast & Airport Transfers, Book with ShohimUl Islam. Email: GOLF TOURNAMENT sales3@asiapaci� ichotelbd.com . Ref : Gol ing Rotarians. Kurmitola Golf Club (KGC) is a veritable heaven for golf enthusiasts in OF GOLFING ROTARIANS (SAFGR) BANGLADESH Registration Fee:� � Bangladesh and other golfers around the world. It is being run under the supervision of Club President, General Aziz Ahmed, BGBM, PBGM, BGBMS, psc, Gents: BDT: 5,000.00 or USD.60.00 Ladies: BDT.4, 000.00 or USD.50.00 G and the Bangladesh Army. KGC is the prettiest and best maintained courses Couple: BDT.8, 000.00 0r USD.95.00 in the sub-continent. The course is strategically challenging and playable round the year. Form is attached. Email: [email protected] MEMBER PAY The history of Kurmitola Golf Club (KGC) dates back to the mid- ifties. Shifting Caddie Fee: BDT.450.00 for 18 Holes from its original location (presently Hazrat Shahjalal International Airport), it BDT.300.00 for 9 Holes inally settled at the present site in the mid-sixties. Initially the� layout of the Golf Cart: BDT.2000.00 for 18 Holes (on 1st Come 1st Base – only 8 Carts) course was done by a keen golfer and architect Mr. -

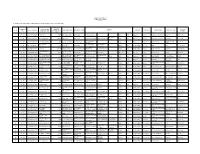

SL.NO WARRANT NO. FOLIO/ BO ID No. NAME of THE

BANK ASIA LIMITED CORPORATE OFFICE DHAKA STATEMENT OF UNCLAIMED CASH DIVIDEND FOR THE YEAR 2014 @ 5% AS ON 29.08.2021 NET CASH WARRANT NAME OF THE DIVIDEND ACCOUNT SL.NO FOLIO/ BO ID No. FATHER'S NAME MOTHER'S NAME ADDRESS COUNTRY PHONE NO BANK NAME BRANCH NAME NO. SHAREHOLDERS FOR THE YEAR NUMBER 2014 1 1401400 1201470000562060 QAIS HUDA 102.00 Late. Shamsul Huda Hossan Banu 43, Fakirapool Bazar Dhaka 1000 Bangladesh 8350651 Standdard Chartered Bank Banani Br. 01628693301 BUET Officers 2 1401401 1201470001836367 REETA RANI DEY 3,243.85 Subrata Paul Horimati Dey Ashutosh Chandra Dey Flat No-406, House-52 Dhaka 1000 Bangladesh 8919144 Standard Chartered Bank Dilkusha Br. 18107515201 Quarter 213, West Rampura Bonoshree Branch, 3 1401403 1201480048616428 TAHAMINA BEGUM 46.75 Late Md. Ataur Rahman Umme Kulshum Dhaka 1219 Bangladesh 01670279102 Dhaka Bank Ltd. 227.200.2744 Wapda Road Rampura MD. MOGBUL MD. SHAMIM C/O-MD. SHAKIL MOTIJHEEL C/A, 4 1401405 1201510003686145 22.74 HOSSAIN NURJAHAN DHAKA 1000 BANGLADESH 7175716 DBBL ANY 105.101.192213 HOSSAIN RIZVI & CO. 9/E 8TH FLOOR, HAWLADAR 46/1 PURANA 5 1401406 1201510025726223 AZOB ALI 7,713.75 LATE MOSROB ALI MOS GULTERA BIBI MUGOLTOLI ROAD DHAKA 1100 DHAKA 1100 BANGLADESH 7122851 BANK ASIA LTD. PRINCIPAL 00003C0700182 MALTULA SONTOSH KUMAR Late Debendra Kumar 18/5, Baghmara Bormon 6 1401409 1201520043630319 778.16 Raj Laxmi Das Mymensingh, Mymensingh 2230 Bangladesh 8124886 Janata Bank Ltd. NRB Br. 407008867 DAS Das Kuthir, MRS. MAHFUTA Rupnagar Abasiq, 7 1401410 1201530000070590 MD. SHAHID -

Developments

Highlights: Camp Conditions: • Two refugees were killed this week in Teknaf, Cox’s Bazar by Bangladesh security forces. More than a dozen Rohingya refugees have been killed in recent weeks. Conditions in Myanmar: • Myanmar faces calls from rights groups to release 30 Rohingya men, women and children arrested in September while trying to travel from Rakhine state to the city of Yangon. A total of 21 Rohingya face up to two years in jail under Myanmar’s Residents of Burma Registration Act. International Justice and Accountability: • Experts will meet at an international conclave on the Rohingya crisis to be held in The Hague, Netherlands on 18 October with the intent of bringing the issue of justice and accountability for Rohingyas into focus. Developments: Raise voice for Rohingya repatriation: Finance Minister to ADB, United News of Bangladesh (13 October) Finance Minister AHM Mustafa Kamal has requested the representatives of the Asian Development Bank (ADB) to raise their voices for the quick repatriation of Rohingyas. ADB representatives have also visited the Rohingyas camps. Similar: Finance minister to ADB: Raise voice for Rohingyas repatriation, Dhaka Tribune (13 Oct.) Rebels Dressed as Soccer Players Abduct Bus Passengers in Myanmar, The New York Times (13 October) Gunmen dressed in soccer uniforms halted an express bus on a main highway in Myanmar’s troubled Rakhine State and kidnapped 31 people, most of them firefighters, the authorities have said. The armed men were identified as members of a rebel group called the Arakan Army. Bangladesh forces kill more than a dozen Rohingya refugees, Al Jazeera (13 October) Security forces in Bangladesh have killed more than a dozen Rohingya refugees in recent weeks. -

Memberships the Institute of Bankers, Bangladesh

01 Letter of Transmittal LeL ttet r of Transmittal All Shareholders of Trust Bank Limited Bangladesh Securities and Exchange Commission Dhaka Stock Exchange Limited Chittagong Stock Exchange Limited Registrar of Joint Stock Companies and Firms Annual Report for the year ended on 31 December 2020. Dear Sir, We are pleased to present a copy of the Annual Report 2020 with Audited Financial Statements. The report includes consolidated and separate Balance Sheet, Profit and Loss Account, Statement of Cash Flows, Statement of Changes in Equity and Liquidity Statement for the year ended on 31 December 2020 with the notes thereto. Statements are prepared on Trust Bank Limited (TBL) and its Subsidiaries and Joint Venture-Trust Bank Investment Limited (TBIL), Trust Bank Securities Limited (TBSL) and Trust Axiata Digital Limited (TADL). Yours Sincerely, Md. Mizanur Rahman, FCS Company Secretary Annual Report 2020 1 01 About Us Trust Bank Limited (TBL) was established as a scheduled bank in 1999 to provide necessary and affordable banking services with optimum value to the people of Bangladesh. With a successful journey of two decades, the Bank has now emerged as a leading, sound and stable commercial private bank in Bangladesh. The Bank offers the entire spectrum of financial services to customer segments, including large and mid-corporates, SME and retail businesses. Trust Bank, the first of its kind in the history of Bangladesh, was initially sponsored by Army Welfare Trust (AWT), Bangladesh Army. The Bank was listed with the Stock Exchanges in 2007 and floated the shares for the general public. At present, AWT is the largest shareholder, holding 60% of the stake of the Bank. -

Grave Allegations Involving Visiting Bangladesh Army Chief

UN: Grave Allegations Involving Visiting Bangladesh Army Chief Documentary Alleges Links Between General Aziz and Security Force Abuses Published in (New York) – The United Nations should use its meetings with senior Bangladeshi military officials next week to protest attempts to use the UN as cover for abuses at home, seven human rights groups said today. The UN should announce a comprehensive review of UN relations with Bangladeshi armed forces, the top troop contributor to peacekeeping missions worldwide. The Bangladesh chief of army staff, Gen. Aziz Ahmed, is scheduled to meet with high-level UN officials next week with the aim of increasing the Bangladesh role in UN peacekeeping. Gen. Aziz is the focus of a disturbing investigation by Al Jazeera alleging involvement of members of his family in abuses by Bangladeshi security forces as well as the commission of grave human rights abuses by military units under his command. “In addition to a long pattern of extrajudicial killings, disappearances, and torture by Bangladesh security forces under Gen. Aziz’s control, new information suggests the Bangladesh military is making a brazen attempt at ‘blue-washing’ the government’s abusive surveillance tactics at home,” said Louis Charbonneau, Human Rights Watch UN director. “The UN should conduct its own inquiry into the allegations and take a fresh look at the human rights record of all Bangladesh units and individuals involved in peacekeeping missions.” The Al Jazeera investigation documented that the government had illegally purchased highly invasive spyware from Israel. The Bangladesh military reacted to the evidence by saying that the equipment was for an “army contingent due to be deployed in the UN peacekeeping mission.” The UN on February 4 denied that it was deploying such equipment with Bangladeshi contingents in UN peacekeeping operations. -

Bangladesh Bank Requirements

Letter of Transmittal l All Shareholders of Trust Bank Limited Bangladesh Securities and Exchange Commission Dhaka Stock Exchange Limited Chittagong Stock Exchange Limited Registrar of Joint Stock Companies and Firms tta Annual Report for the year ended on 31 December 2019. Dear Sir, mi We are pleased to present a copy of the Annual Report 2019 with Audited s Financial Statements. The report includes consolidated and separate Balance Sheet, Profit and Loss Account, Statement of Cash Flows, Statement of n Changes in Equity, Liquidity Statement for the year ended on 31 December 2019 with the notes thereto. Statements are prepared on Trust Bank Limited a (TBL) and its Subsidiaries-Trust Bank Investment Limited (TBIL) and Trust Bank Securities Limited (TBSL). Tr Yours Sincerely, f o Md. Mizanur Rahman, FCS r Company Secretary ette L About Us Trust Bank Limited (TBL) was established as a scheduled bank in 1999 to ensure useful and affordable banking services with optimum value to the people of Bangladesh. With a successful journey of 20 years, the Bank has emerged as a leading, sound and stable commercial private bank in Bangladesh. The Bank offers the entire spectrum of financial services to customer segments, spanning large and mid-corporates, SME and retail businesses. Trust Bank, first of its kind in the history of Bangladesh, was initially sponsored by Army Welfare Trust (AWT) of Bangladesh Army. In 2007, the Bank listed itself with the stock exchanges and floated the shares for general public. Now, AWT is the largest shareholder, holding 60% of stake of the Bank. Over the years, the Bank has developed long-term relationship with its customers by being their preferred financial solutions partners, leveraging profound insights and superior services. -

Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited

Dutch-Bangla Bank Limited Board Secretariat, Head Office, Dhaka Unpaid/Uncollected/Unclaimed Dividend Amount for the year 2009 Name of the sharesholders/ Securities Nominee If Net amount SL# Father's Name BO/Folio Number Permanent & Contact Address holders any of Dividend 1 RAFIQUL ISLAM KHAN LATE MD. BELAYET KHAN 05-000108 402.66 2 S.M. MASUDUL HAQUE M A SALAM 05-000172 105 SULTAN AHMED ROAD MAULAVIPARA 402.66 3 SAJEDA YUSUF MD YUSUF 05-000235 AO#-1B,H#-14,R#-11,SE#-7, UTTARA. 805.32 4 MD.RASHEDUZZAMAN MD ASGHAR ALI 05-000239 PLOT NO-96,RASOOL PUR,DHAKA,JA TTRABARI 805.32 D-15/A RAILWAY OFFICER`S COLONY SHAJAHANPUR, 5 SATYA BRATA NARAYAN CHOWDHURY AL-HAJ M.A. SAMAD 05-000576 DHAKA-1217 1610.64 FLAT NO. K-9, BAILY RITZ, 1 NEW BAILY ROAD, 6 MD. ZAKARIA Helal Uddin Ahmed 05-000659 DHAKA-1217. 1207.98 HOUSE-37(2ND FL.),BLOCK-KHA, P.C.CULTURE 7 MS. NASREEN HUSSAIN 05-001261 HOUSING SOCICTY, SHAKERTEK,MOHAMMADPUR 402.66 GA, B-2, E/5, AGARGAON NEW COLLONI, SHER-E 8 R.M.SHIBLEE MEHDI 05-001390 BANGLA NAGAR 1207.98 391, ELEPHANT ROAD ISMAIL MANSION 2ND FLOOR, 9 MD. TOFAZZAL HOSSAIN BHUYAN Gopendra Narayan Chowdhury 05-001391 SHOP NO-15 805.32 6/C, RUSSELL LODGE, 32/4-A, SHAHJAHAN ROAD 10 MR. M. I. AKRAM 1201470000013799 MOHAMMADPUR 805.32 BUILDING NO -2, HOUSE NO 22 GOVT PRINTING 11 KHANDAKER MOFEJUL ISLAM 1201470001896684 PRESS STAFF QUT. TEJGAON I/A 402.66 FLAT-5A BOROBARI,134/B, WEST KAFRUL,NEAR OF 12 MD. -

COVID-19 in Bangladesh: How the Awami League Transformed a Crisis Into a Disaster

Volume 18 | Issue 15 | Number 10 | Article ID 5444 | Aug 01, 2020 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus COVID-19 in Bangladesh: How the Awami League Transformed a Crisis into a Disaster Ikhtisad Ahmed public relations extravaganza suits autocrats Abstract: In the case of Bangladesh, COVID-19 like Rahman’s daughter, Prime Minister Sheikh has laid bare the shortcomings of the state, Hasina. The 2018 re-election campaign underscoring the complicity of the military, platform of the Awami League declared that it elite class, Islamists and intelligentsia in the was the only party that could guarantee government’s dysfunctional, apathetic, and Bangladesh’s history was properly respected, authoritarian approach. This essay breaks citing these upcoming celebrations as evidence down the Bangladeshi government’s response of its commitment to doing so. Although the along three key lines: the first to examine the rigged election denied the Awami League the legal basis for its response to the pandemic, the veneer of democratic legitimacy, it was hoped second the exploitation of labour rights and that the nationalist pageantry would provide a how it affects public image, and third the positive limelight. Taxpayers would provide suppression of freedoms of speech andmuch of the funding for the two-year expression. Through discussion of these key saturnalia, supplemented by large donations tenets, this essay provides a comprehensive from cronies who have done well from their indictment of how Bangladesh is turning a connections to the Awami League. But things crisis into a disaster. did not go according to plan. In Bangladesh, the emperor unquestionably has the best clothes. -

11 June -2021

DAILY UPDATED CURRENT AFFAIRS: 11 JUNE -2021 .12.2018 NATIONAL Govt increases kharif MSP.2018 of kharif crops by an average 3.7 per cent The Central government increased the Minimum Support Price (MSP) of kharif crops for the 2021-21 crop.11.2018 season (July-June) by an average 3.7 per cent as compared to the previous year with the maximum hike reserved for pulses and oilseeds to encourage farmers to shift from paddy. The MSP of tur and urad has been increased by Rs 300 per quintal in absolute terms for 2021-22 to Rs 6300 per quintal while the MSP of groundnut seed has been increased by Rs 275 per quintal in 2021-21 to Rs 5550 per quintal. BANKING AND ECONOMIC PayNearby tie-up with IndiaFirst Life Insurance Launched– ‘Poorna Suraksha’ Insurance solutions for Retailers PayNearby has launched an insurance solution ‘Poorna Suraksha’ for its retail community. This exclusive and holistic insurance solution will ensure the safety and security of PayNearby’s 15+ lakh retail partners across 17,500+ PIN codes. This cost-effective, three-in-one solution was created in collaboration with IndiaFirst Life InsuranceCompany Limited (IndiaFirst Life) to protect PayNearby’s retailers throughout the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond, ensuring they have access to a safety net whenever and wherever they need it. PayNearby’s Poorna Suraksha insurance echoes this philosophy by providing coverage for all areas of insurance – life, health, and disability – at an affordable premium. STATE GOVT NEWS Assam govt announced its seventh national park with Dehing Patkai The Government of Assam has notified Dehing Patkai as a National Park.