The Population of Chartham from 1086 to 1600

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Document in Detail: Diocese of Canterbury Medieval Fragments

Issue 10, Summer 2018 Kent Archives is set for a busy summer. In this edition of our newsletter we introduce you to our joint project with Findmypast to digitise our parish register collection. The image in our header is from the first Cranbrook parish composite register [ref. P100/1/A/1], and is just one of the thousands of registers that will be digitised. We are also in the middle of transferring the remaining historic records of the Diocese of Canterbury from Canterbury Cathedral Archives to the Kent History and Library Centre to join its probate records, which have been held by Kent Archives since 1946. At the same time, archive cataloguing of one of Maidstone’s major papermaking collections is nearly complete; further World War I commemorative activities are underway; and work continues on the Catalogue Transfer Project and Manorial Documents Register Project for Kent. Document in Detail: Diocese of Canterbury Medieval Fragments [DCb/PRC/50/5] Mark Ballard, Archive Service Officer Among many other records of great value within the records of Canterbury Diocese are the ‘medieval fragments’ [DCb/PRC/49 and DCb/PRC/50], which in the post-Reformation period came to be used as covers, or ‘end-parchments’, for the probate registers. If we can judge by the dates of the act books and wills and inventories registers they covered, this recycling became a habit during the episcopate of Archbishop Matthew Parker (1559-1575). It is perhaps ironic that at precisely the time that Thomas Tallis and William Byrd, probably both closet Roman Catholics, were still being employed to write motets for the Chapel Royal, such disrespectful treatment was being accorded at Canterbury to their medieval predecessors. -

Kent Archæological Society Library

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society KENT ARCILEOLOGICAL SOCIETY LIBRARY SIXTH INSTALMENT HUSSEY MS. NOTES THE MS. notes made by Arthur Hussey were given to the Society after his death in 1941. An index exists in the library, almost certainly made by the late B. W. Swithinbank. This is printed as it stands. The number given is that of the bundle or box. D.B.K. F = Family. Acol, see Woodchurch-in-Thanet. Benenden, 12; see also Petham. Ady F, see Eddye. Bethersden, 2; see also Charing Deanery. Alcock F, 11. Betteshanger, 1; see also Kent: Non- Aldington near Lympne, 1. jurors. Aldington near Thurnham, 10. Biddend.en, 10; see also Charing Allcham, 1. Deanery. Appledore, 6; see also Kent: Hermitages. Bigge F, 17. Apulderfield in Cudham, 8. Bigod F, 11. Apulderfield F, 4; see also Whitfield and Bilsington, 7; see also Belgar. Cudham. Birchington, 7; see also Kent: Chantries Ash-next-Fawkham, see Kent: Holy and Woodchurch-in-Thanet. Wells. Bishopsbourne, 2. Ash-next-Sandwich, 7. Blackmanstone, 9. Ashford, 9. Bobbing, 11. at Lese F, 12. Bockingfold, see Brenchley. Aucher F, 4; see also Mottinden. Boleyn F, see Hever. Austen F (Austyn, Astyn), 13; see also Bonnington, 3; see also Goodneston- St. Peter's in Tha,net. next-Wingham and Kent: Chantries. Axon F, 13. Bonner F (Bonnar), 10. Aylesford, 11. Boorman F, 13. Borden, 11. BacIlesmere F, 7; see also Chartham. Boreman F, see Boorman. Baclmangore, see Apulderfield F. Boughton Aluph, see Soalcham. Ballard F, see Chartham. -

KENT. Canterbt'ry, 135

'DIRECTORY.] KENT. CANTERBt'RY, 135 I FIRE BRIGADES. Thornton M.R.O.S.Eng. medical officer; E. W. Bald... win, clerk & storekeeper; William Kitchen, chief wardr City; head quarters, Police station, Westgate; four lad Inland Revilnue Offices, 28 High street; John lJuncan, ders with ropes, 1,000 feet of hose; 2 hose carts & ] collector; Henry J. E. Uarcia, surveyor; Arthur Robert; escape; Supt. John W. Farmery, chief of the amal gamated brigades, captain; number of men, q. Palmer, principal clerk; Stanley Groom, Robert L. W. Cooper & Charles Herbert Belbin, clerk.s; supervisors' County (formed in 1867); head quarters, 35 St. George'l; street; fire station, Rose lane; Oapt. W. G. Pidduck, office, 3a, Stour stroot; Prederick Charles Alexander, supervisor; James Higgins, officer 2 lieutenants, an engineer & 7 men. The engine is a Kent &; Canterbury Institute for Trained Nur,ses, 62 Bur Merryweather "Paxton 11 manual, & was, with all tht' gate street, W. H. Horsley esq. hon. sec.; Miss C.!". necessary appliances, supplied to th9 brigade by th, Shaw, lady superintendent directors of the County Fire Office Kent & Canterbury Hospital, Longport street, H. .A.. Kent; head quarters, 29 Westgate; engine house, Palace Gogarty M.D. physician; James Reid F.R.C.S.Eng. street, Acting Capt. Leonard Ashenden, 2 lieutenant~ T. & Frank Wacher M.R.C.S.Eng. cOJ1J8ulting surgeons; &; 6 men; appliances, I steam engine, I manual, 2 hQ5l Thomas Whitehead Reid M.RC.S.Eng. John Greasley Teel!! & 2,500 feet of hose M.RC.S.Eng. Sidney Wacher F.R.C.S.Eng. & Z. Fren Fire Escape; the City fire escape is kept at the police tice M.R.C.S. -

A Guide to Parish Registers the Kent History and Library Centre

A Guide to Parish Registers The Kent History and Library Centre Introduction This handlist includes details of original parish registers, bishops' transcripts and transcripts held at the Kent History and Library Centre and Canterbury Cathedral Archives. There is also a guide to the location of the original registers held at Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre and four other repositories holding registers for parishes that were formerly in Kent. This Guide lists parish names in alphabetical order and indicates where parish registers, bishops' transcripts and transcripts are held. Parish Registers The guide gives details of the christening, marriage and burial registers received to date. Full details of the individual registers will be found in the parish catalogues in the search room and community history area. The majority of these registers are available to view on microfilm. Many of the parish registers for the Canterbury diocese are now available on www.findmypast.co.uk access to which is free in all Kent libraries. Bishops’ Transcripts This Guide gives details of the Bishops’ Transcripts received to date. Full details of the individual registers will be found in the parish handlist in the search room and Community History area. The Bishops Transcripts for both Rochester and Canterbury diocese are held at the Kent History and Library Centre. Transcripts There is a separate guide to the transcripts available at the Kent History and Library Centre. These are mainly modern copies of register entries that have been donated to the -

Term 2 Term 3 Term 1 Term 4 Term 5 Term 6

Canterbury LIFT Meetings 2021/2022 Deadline for submitting Group Date Time Venue paperwork (by 5pm) EY LIFT (Grp A) Mon 20 Sep 09:30 Canterbury Academy (PLCC) 10-Sep 1 Tues 21 Sep 09:30 Virtual 11-Sep EY Forum - Canterbury Mon 27 Sep 09:30 Canterbury Academy (PLCC) n/a 3 Weds 29 Sep 13:30 Spires 20-Sep 4 Thurs 30 Sep 09:30 Herne Infants 21-Sep 2 Tues 5 Oct 09:30 Canterbury Academy (PLCC) 27-Sep Settings - EHCP mtg Thurs 7 Oct 09:30 Virtual n/a Term 1 EY LIFT (Grp B) Tues 12 Oct 09:30 Virtual 04-Oct ISG / EXEC Thurs 14 Oct 09:30 Canterbury Academy (PLCC) n/a 5 Weds 13 Oct 09:30 Virtual 05-Oct EY LIFT (Grp A / B) Tues 19 Oct 09:30 Virtual 11-Oct EY LIFT (Grp B) Mon 1 Nov 09:30 Windchimes 20-Oct 1 Thurs 4 Nov 13:30 Canterbury Academy (PLCC) 21-Oct 4 Mon 8 Nov 09:30 Virtual 01-Nov 3A Fri 12 Nov 13:30 Virtual 03-Nov EY LIFT (Grp A) Weds 17 Nov 09:30 Canterbury Academy (PLCC) 09-Nov 2 Thurs 18 Nov 09:30 Canterbury Academy (PLCC) 10-Nov EY Forum - Canterbury Mon 22 Nov 09:30 Canterbury Academy (PLCC) n/a ISG / EXEC Thurs 25 Nov 09:30 Canterbury Academy (PLCC) n/a Term 2 Settings - EHCP mtg Mon 29 Nov 09:30 Virtual n/a 5 Weds 1 Dec 09:30 Herne Junior 23-Nov EY LIFT (Grp A /B) Tues 7 Dec 09:30 Virtual 29-Nov 3B Weds 8 Dec 13:30 Spires 30-Nov EY LIFT (Grp A) Mon 10 Jan 09:30 Canterbury Academy (PLCC) 16-Dec Settings - EHCP mtg Tues 11 Jan 09:30 Virtual 17-Dec 1 Thurs 13 Jan 13:30 Canterbury Academy (PLCC) 04-Jan 4 Thurs 20 Jan 09:30 Herne Infants 12-Jan EY LIFT (Grp B) Tues 25 Jan 09:30 Windchimes 17-Jan 3 Weds 26 Jan 13:30 Spires 18-Jan EY LIFT -

The Kent Yeoman in the Seventeenth Century

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society THE KENT YEOMAN IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY JACQUELINE BOWER Mildred Campbell, in the only detailed work so far published on the yeomanry, concluded that the yeoman class emerged in the fifteenth century.1 The yeomen were the free tenants of the manor, usually identified with freeholders of land worth 40s. a year, the medieval franklins. The Black Death of 1348 may have hastened the emergence of the yeomanry. The plague may have killed between one-third and one-half of the total population of England, a loss from which the population did not recover until the second half of the sixteenth century. Landowners were left with vacant farms because tenants had died and no one was willing to take on tenancies or buy land at the high rents and prices common before the Black Death. In a buyer's market, it became impossible for landlords to enforce all the feudal services previously exacted. Land prices fell, and peasant farming families which survived the Black Death and which had a little capital were able, over several generations, to accumulate sizeable estates largely free of labour services. It is taken for granted that yeomen were concerned with agriculture, men who would later come to be described as farmers, ranking between gentry and husbandmen, of some substance and standing in their communities. However, a re-examination of contemporary usages suggests that there was always some uncertainty as to what a yeoman was. William Harrison, describing English social structure in 1577, said that yeomen possessed 'a certain pre-eminence and more estimation' among the common people. -

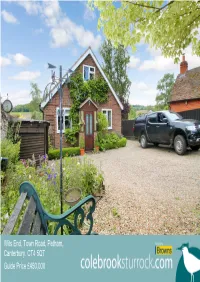

Wits End, Town Road, Petham, Canterbury, CT4 5QT Guide Price £450,000

Wits End, Town Road, Petham, Canterbury, CT4 5QT Guide Price £450,000 Wits End Town Road, Petham, Canterbury Deceptively spacious detached chalet style bungalow with three reception rooms, two bath/shower rooms, and four bedrooms; set within gated gardens and offering wonderful open views. No Chain. EPC E Situation Wits End is well located close to the centre of the A rear hallway has a utility area and also gives village of Petham; which is a small unspoilt rural access to bedroom four and a shower room/WC, village offering not only excellent access routes, a while a further be droom can be found at the front Grade I Listed Church, active village hall, excellent of the property along with an additional bathroom. public house/restaurant and a Primary School b ut Upstairs are two good size bedrooms with the a number of walks and rides through beautiful rear bedroom having built-in wardrobes and scenic countryside forming part of the Kent Downs fabulous rural views. Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. In a mere five to ten minutes you can be within the Outside historic Cathedral City of Canterbury with its The front gardens are well enclosed laid mainly to eclectic mix of shop s, restaurants, supermarkets, shi ngle for ample parking with an attractive flint golf course, theatre, sports facilities and wall and ranch style gates. outstanding schools, including the Simon Langton A large area of decking adjacent to the rear of the Grammar Schools, and much more. property is an idyllic spot for al fresco dining and Commuting services are excellent with the high to enjoy the fantastic countryside views; along speed transport links to London St Pancras via with a further area of pat io and neat lawn with Sandl ing and Folkestone West Stations and of outbuildings, log store and garden shed. -

Waddenhall Farm, Petham, Canterbury, Kent, CT4 5PX

Waddenhall Farm Petham, Canterbury Kent CT4 5PX Address Address Waddenhall Farm, Petham, Canterbury, Kent, CT4 5PX A highly productive ring fenced fruit farm extending to approximately 96.86 acres (39.20 hectares), benefitting from a useful vernacular building. For sale as a whole or in two lots. Situation The farm is situated to the west of Stone Street (B2068), between the villages of Waltham and Bossingham, to the south of the Cathedral City of Canterbury. The nearest postcode is CT4 5PX. Directions From the Old Dover Road in Canterbury head towards Folkestone on the Nackington Road (B2068) after approximately 5½ miles take a right hand turn off Stone Street onto The Gogway, the farm entrance is on your right hand side after about 0.8 miles. From the M20 take the exit at junction 11, following the B2068 towards Canterbury. After approximately 7 ½ miles turn left on to The Gogway, the farm entrance is on your right hand side after about 0.8 miles. Description Waddenhall Farm is a useful block of land planted with high yielding varieties of apples in about 2004. Much of the land is surrounded by woodland, making the farm suitable for polytunnels and other protected growing environments, subject to obtaining the necessary planning consents. The two lots are described below: Lot 1 Lot 1 comprises 38.80 hectares (95.87 acres), divided into six main parcels, planted with a mixture of Braeburn, Early Windsor and Bramley apples. A detailed breakdown of the cropping is outlined below, which includes tree numbers. In addition there is a small area of woodland located on the western side of the farm of approximately 1.42 hectares (3.50 acres). -

Annual Bibliography of Kentish Archaeology and History 2008

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society ANNUAL BIBLIOGRAPHY OF KENTISH ARCHAEOLOGY AND HISTORY 2008 Compiler: Ms D. Saunders, Centre for Kentish Studies. Contributors: Prehistoric - K. Partitt; Roman - Dr E. Swift, UKC; Anglo-Saxon - Dr A. Ricliardson, CAT; Medieval - Dr C. Insley, CCCU; Early Modern - Prof. J. Eales, CCCU; Modern - Dr C.W. Chalklin and Prof. D. Killingray. A bibliography of books, articles, reports, pamphlets and theses relating specifically to Kent or with significant Kentish content. All entries were published in 2008 unless otherwise stated. GENERAL AND MULTI-PERIOD M. Ballard, The English Channel: the link in the history of Kent and Pas-de- Catais (Arras: Conseil General du Pas-de-Calais, in association with KCC). P, Bennett, P. Clark, A. Hicks, J, Rady and I. Riddler, At the great crossroads: prehistoric, Roman and medieval discoveries on the Isle of Thane 11994-1995 (Canterbury: CAT Occas, Paper No. 4). C. Bumham, Hinxhill: a historical guide (Wye: Wye Historical Soc). CAT, Annual Report: Canterbury's Archaeology 2006- 7 (Canterbury). J. Hodgkinson, The Wealden iron industry (Stroud: Tempus). G, Moody, The Isle ofThanetfrom prehistory to the Norman Conquest (Stroud: Tempus). A. Nicolson, Sissinghurst, an unfinished history (London: Harper Press). J. Priestley, Eltham Palace: royalty architecture gardens vineyards parks (Chichester: Phillimore). D. Singleton, The Romney Marsh Coastline: from Hythe to Dungeness (Stroud: Sutton). M. Sparks, Canterbury Cathedral Precincts: a historical survey (Canterbury: Dean and Chapter of Canterbury, 2007). J. Wilks, Walks through history: Kent (Derby: Breedon). PREHISTORIC P. Ashbee, 'Bronze Age Gold, Amber and Shale Cups from Southern England and the European Mainland: a Review Article', Archaeotogia Cantiana, cxxvm, 249-262. -

1 2 3 RENTAIN ROAD CHARTHAM North- West Across the Frontage Of

THE KENT COUNTY COUNCIL (CANTERBURY RURAL PARISHES) (TRAFFIC REGULATION AND STREET PARKING PLACES) (AMENDMENT No. 2) ORDER 2013 The Council of the County of Kent in exercise of their powers under sections 1(1), 2(1) to (3), 3(2), 4(1) and 4(2), 32(1), 35(1), 45, 46, 49 and 53 of the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984, and of all other enabling powers, and after consultation with the chief officer of police in accordance with Paragraph 20 of Schedule 9 to the Act, hereby make the following Order: A - This Order may be cited as the Kent County Council (Canterbury Rural Parishes) (Traffic Regulation and Street Parking Places) (Amendment No. 2) Order 2013 and shall come into operation on the 13th May 2013. B - Kent County Council (Canterbury Rural Parishes) (Traffic Regulation and Street Parking Places) (Consolidation) Order 2012 shall have effect as though: In the Articles to the Order: RENTAIN ROAD, STURRY COURT MEWS AND SY JOHN’S CRESCENT The following to be inserted in the Table to Article 30 - 1 2 3 Name of Road side of Specified length road RENTAIN CHARTHAM north- across the frontage of 41 ROAD west Rentain Road ST JOHN’S HACKINGTON west between 2 metres south and 6 CRESCENT metres north of a point in line with the common boundary of 10 and 11 St John's Crescent STURRY STURRY west from a point in line with the COURT MEWS southern flank wall of 16 Sturry Court Mews for 10 metres in a northerly direction. In the Schedules to the Order: Roads in the Parish of Blean BLEAN COMMON The following to be inserted in the First Schedule – Page 1 -

THE KENT COUNTY COUNCIL (CANTERBURY RURAL PARISHES) (TRAFFIC REGULATION and STREET PARKING PLACES) (AMENDMENT No 3) ORDER 2002

THE KENT COUNTY COUNCIL (CANTERBURY RURAL PARISHES) (TRAFFIC REGULATION AND STREET PARKING PLACES) (AMENDMENT No 3) ORDER 2002 Notice is hereby given that KENT COUNTY COUNCIL propose to make the above named Order, under sections 1(1), 2(1) to (3), 3(2), 4(1) and 4(2), 32(1), 35(1), 45, 46, 49 and 53 of the road Traffic Regulation Act 1984, and of all other enabling powers, and after consultation with the chief officer of police in accordance with Paragraph 20 of Schedule 9 to the Act: The effect of the Order will be to introduce changes to waiting restrictions, parking places and formalise disabled drivers parking bays on the following roads or lengths of roads: - - SWEECHGATE - BROAD OAK CHURCH ROAD - LITTLEBOURNE STATION ROAD - CHARTHAM -- CHAFY CRESCENT - STURRY THE GREEN - CHARTHAM MILL ROAD - STURRY -:- FAULKNERS LANE - HARBLEDOWN --ASHENDEN CLOSE - THANINGTON - FORDWICH ROAD - FORDWICH WITHOUT MARLOW MEADOWS - FORDWICH --- STRANGERS CLOSE - THANINGTON THE MALTINGS - LITTLEBOURNE WITHOUT JUBILEE ROAD - LITTLEBOURNE STRANGERS LANE - THANINGTON HIGH STREET - LITTLEBOURNE WITHOUT Full details are contained in the draft Order which together with the relevant plans, any Orders, amended by the proposals and a statement of reasons for proposing to make the Order may be examined on Mondays to Fridays at the Council Offices, Military Road, Canterbury Between 8.30am and 5pm and in Sturry Library during normal opening hours. If you wish to offer support for or object to the proposed Order you should send the grounds in writing to the Highway Manager, Council Offices, Military Road, Canterbury, CT1 1YW by noon on Tuesday 7 May 2002. -

No Man's Orchard

NO MAN’S ORCHARD Orchards - traditional and modern Traditional orchards with old fruit trees are rapidly disappearing in The name “No Man’s” was traditionally given to land that straddled Kent. They are less profitable than modern commercial orchards, more than one parish – no one man’s land. At No Man’s Orchard but nevertheless they provide important habitats for wildlife. The this is supported by the fact that the parish boundary of Chartham trees have very large spreading crowns and are far taller than in and Harbledown runs across the centre of the site.The orchard was modern commercial orchards, which have been specially cultivated purchased by Chartham and Harbledown Parish Councils in 1996. for ease of picking. North Downs Way to Harbledown No Man’s Orchard Interpretive North Downs Way panel to Chartham Cider apple varieties Serpent seat Harbledown parish Chartham parish A modern commercial orchard The orchard is a peaceful and inviting place in all seasons, as beautiful in blossom-time as when a fair apple crop is ripe. In winter enjoy the character of the gnarled old trunks and huge branches, many now showing their age and leaning heavily, their decline providing homes to an even greater wealth of life. When a tree reaches the end of its lifespan it is replaced with a new planting of suitable traditional variety. Apple trees The orchard, covering eight acres of mainly Bramley apple trees, A locally important site was planted in 1947. Six cider apple varieties at the eastern end Canterbury City Council has designated the orchard a Local Nature were planted in 1996 on a further two acres.