Two Steps Forward, One Step Back: a Brief History of Corporate Citizenship and Corporate Social Responsibility

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

The Rate and Direction of Inventive Activity Revisited

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: The Rate and Direction of Inventive Activity Revisited Volume Author/Editor: Josh Lerner and Scott Stern, editors Volume Publisher: University of Chicago Press Volume ISBN: 0-226-47303-1; 978-0-226-47303-1 (cloth) Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/lern11-1 Conference Date: September 30 - October 2, 2010 Publication Date: March 2012 Chapter Title: The Rate and Direction of Invention in the British Industrial Revolution: Incentives and Institutions Chapter Authors: Ralf R. Meisenzahl, Joel Mokyr Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c12364 Chapter pages in book: (p. 443 - 479) 9 The Rate and Direction of Invention in the British Industrial Revolution Incentives and Institutions Ralf R. Meisenzahl and Joel Mokyr 9.1 Introduction The Industrial Revolution was the fi rst period in which technological progress and innovation became major factors in economic growth. There is by now general agreement that during the seventy years or so traditionally associated with the Industrial Revolution, there was little economic growth as traditionally measured in Britain, but that in large part this was to be expected.1 The sectors in which technological progress occurred grew at a rapid rate, but they were small in 1760, and thus their effect on growth was limited at fi rst (Mokyr 1998, 12– 14). Yet progress took place in a wide range of industries and activities, not just in cotton and steam. A full description of the range of activities in which innovation took place or was at least attempted cannot be provided here, but inventions in some pivotal industries such as iron and mechanical engineering had backward linkages in many more traditional industries. -

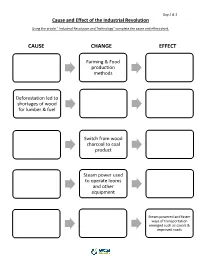

Cause Change Effect

Day 2 & 3 Cause and Effect of the Industrial Revolution Using the article “ Industrial Revolution and Technology” complete the cause and effect chart. CAUSE CHANGE EFFECT Farming & Food production methods Deforestation led to shortages of wood for lumber & fuel Switch from wood charcoal to coal product Steam power used to operate looms and other equipment Steam powered and faster ways of transportation emerged such as canals & improved roads Day 3 & 4 Industrial Revolution Timeline 1721: Cromford Mill was the first factory with the first water powered cotton spinning mill. 1733: Flying Shuttle made weaving faster, invented by John Kay. 1760: Industrial Revolution begins in England 1767: Spinning Jenny, a machine that can spin thread more quickly was invented James 1769: Water Frame, improved the Spinning Hargreaves. Jenny, ran on water instead of human labor. 1783: Henry Cort patented the puddling process which allowed wrought iron to be produced in large quantities. 1784: Steam Powered Loom that turned thread into cloth is invented by Edmund Cartwright. 1792-3: Eli Whitney invents the cotton gin, changing the textile sector. Now cotton fiber was separated from seeds through machine. 1831: Electric Generator led to improvements to create the first generator to support a factory. Invented by Michael Faraday. 1837: Telegraph made transmission of messages easier. Invented by William Fothergill & Charles Wheatstone. 1856: Bessemer Converter was the first process of manufacturing steel that wasn’t expensive. Day 3 & 4 Sources Brodsky Schur, J. (2016, September 23). Eli Whitney's Patent for the Cotton Gin. Retrieved June 22, 2021, from http://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/cotton-gin-patent Karpiel, F., Krull, K., & Wiggins, G. -

History of Metallurgy

History of Metallurgy by Rochelle Forrester Copyright © 2019 Rochelle Forrester All Rights Reserved The moral right of the author has been asserted Anyone may reproduce all or any part of this paper without the permission of the author so long as a full acknowledgement of the source of the reproduced material is made. Second Edition Published 30 September 2019 Preface This paper was written in order to examine the order of discovery of significant developments in the history of metallurgy. It is part of my efforts to put the study of social and cultural history and social change on a scientific basis capable of rational analysis and understanding. This has resulted in a hard copy book How Change Happens: A Theory of Philosophy of History, Social Change and Cultural Evolution and a website How Change Happens Rochelle Forrester’s Social Change, Cultural Evolution and Philosophy of History website. There are also philosophy of history papers such as The Course of History, The Scientific Study of History, Guttman Scale Analysis and its use to explain Cultural Evolution and Social Change and Philosophy of History and papers on Academia.edu, Figshare, Humanities Commons, Mendeley, Open Science Framework, Orcid, Phil Papers, SocArXiv, Social Science Research Network, Vixra and Zenodo websites. This paper is part of a series on the History of Science and Technology. Other papers in the series are The Invention of Stone Tools Fire The Neolithic Revolution The Invention of Pottery History -

An Industrial Revolution in Iron—Technology, Organisation and Markets, 1760–1870

CHAPTER FOUR AN INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION IN IRON—TECHNOLOGY, ORGANISATION AND MARKETS, 1760–1870 Baltic iron had come to dominate the British market because of the incapacity of Britain’s own forge sector. British ironmasters lacked the energy resources to keep pace with the heightening demand for mal- leable iron on their domestic market. Some ironmasters sought to over- come this de ciency by organisational means. They hoped to raid the abundant energy reserves of British North America by transferring the preliminary stages of the production chain to the colonies. An Atlantic iron trade, with smelting out-sourced to the charcoal-rich plantations, would be a reproof to the ‘Ignorance & wrong reasonings’ of those Swedish ministers who maintained ‘that England can not be without their Iron’.1 That hope was, as we have seen, thwarted. The alternative to organisational re-jigging was technological transfor- mation. Technological revolution there was, as every textbook on British economic history makes clear. Smelting with coke and the development of coal- red re\ ning methods, most notably Henry Cort’s puddling technique, freed the British iron industry from its dependence upon vegetable fuel in spectacular fashion. Yet technological change could not be conjured up at will. The development of effective coal-based tech- nologies was a drawn-out, tortuous business. Some elements of the ‘coal technology package’ were present by the rst decade of the eighteenth century, but it was not until the 1790s that the iron industry turned fully to a mineral fuel platform. Indeed, it was not until the Napoleonic era that the combination of coke smelting, puddling furnaces, rolling mills, and steam power became the industry standard. -

Historische Rundschau-12-E-Korr.Indd

Bank and History Historical Review No. 38 February 2018 La bella banca 100 years ago Banca d’America e d’Italia was founded. Deutsche Bank acquired it in 1986, and since 1994 it has been called “Deutsche Bank SpA”. Origins and founder The first four years of BAI‘s existence, following its foundation in Naples on 14 November 1917, already gives a clue as to the strongly international char- acter that the bank was to develop during the coming years. It was founded by a group of Italian businessmen under the name ‘Banca dell‘Italia Meridionale’, and already in August of its second year of operations the bank was appoint- ed as representative in Italy for two US banks: Bank of Italy and East River National Bank. The first chairman, Giuseppe Caravita, Prince of Sirignano (died in 1920), was one of the prime movers behind the initiative. The deputy chairman was Giuseppe Di Luggo, the managing director was Carlo Caprioli. The bank opened for business on 15 June 1918 in what would prove to be a difficult period immediately after the end of the Great War. Its capital was immediately increased from 3 million lire to 15 million lire and premises were rented in Naples at 11 Via Santa Brigida, in the same street where Deutsche Bank still has its main Naples office. The bank opened to the public even though building work on the premises was not finished until early 1920. In its 1919 annual report the bank writes, with charming sincerity, that „all shareholders, who know in what conditions our beloved officers and staff have to work, will want to thank them warmly, and will also want to extend their thanks to the customers, who have, perforce, to be received in cramped and unsuitable premises but who have never complained and have always praised the speed Banca dell‘Italia Meridionale in Naples with which the bank works and the politeness and competence of our staff“. -

Millionaires and Managers

CONTENTS Page Preface to the English Edition .................................................. 5 Chapter I. EVOLUTION OE CAPITAL AND OF THE CAPITALIST ............................................................. 7 Chapter II. THE VERY RICH.................................................. 25 1. American Plutocracy in the 1960s .... 25 2. The Old Fortunes............................................................ 42 3. Replenishment of the Plutocracy .... 54 4. "Diminishing Social Inequality" and "People's Capitalism"..................................................................... 69 Chapter III. MANAGERS AT THE TOP ... SO 1. Social Nature of the Managerial Top Echelon 80 2. The Formation of the Managerial Elite . 91 3. The "Market" of Top Executives .... 100 4. Various Interpretations of the Social Position of Top Management ...................................................... 116 Chapter IV. DEVELOPMENT OF BANK MONOP- OLIES AND BANK GROUPS ....................................... 135 1. Further Evolution of Capitalist Property . 135 2. The Bank Monopoly System......................................... 139 Chapter V. FINANCE CAPITAL. ITS FORMS AND COMPONENTS.................................................................. 158 1. Intertwining of the Capital or the "Partici- pation System" ............................................................... 160 2. Long-Standing Financial Ties......................................... 171 3. Personal Union ............................................................. 184 4. Self-Financing -

The Contributions of Warfare with Revolutionary and Napoleonic France to the Consolidation and Progress of the British Industrial Revolution

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by LSE Research Online Economic History Working Papers No: 264/2017 The Contributions of Warfare with Revolutionary and Napoleonic France to the Consolidation and Progress of the British Industrial Revolution Revised Version of Working Paper 150 Patrick O’Brien London School of Economics St Anthony’s College, Oxford Economic History Department, London School of Economics and Political Science, Houghton Street, London, WC2A 2AE, London, UK. T: +44 (0) 20 7955 7084. F: +44 (0) 20 7955 7730 LONDON SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS AND POLITICAL SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMIC HISTORY WORKING PAPERS NO. 264 – JUNE 2017 The Contributions of Warfare with Revolutionary and Napoleonic France to the Consolidation and Progress of the British Industrial Revolution Patrick Karl O’Brien London School of Economics St Anthony’s College, Oxford “Great Britain is under weightier obligation to no mortal man than to this very villain. For whereby the occurrences whereof he is the author, her greatness prosperity, and wealth, have attained their present elevation.” A Prussian General’s reference to Napoleon at the Congress of Vienna, 18151 Abstract This revised and reconfigured essay surveys a range of printed secondary sources going back to publications of the day (as well as includes research in primary sources) in order to revive a traditional and unresolved debate on economic connexions between the French and Industrial Revolutions. It argues that the costs flowing from the reallocation of labour, capital -

Industrial Revolution Version H 1. the Industrial Revolution Lasted Just

Industrial_Revolution version H 1. The Industrial Revolution lasted just under _____ years a) 50 b) 200 c) 1000 d) 600 e) 400 2. On the eve of the Industrial Revolution, when the textile industry was largely a cottage industry, women did the ______ and men did the _______. If a loom was used, the work done by the women required ______ person hours. a) spinning, weaving, more b) weaving, spinning, fewer c) weaving, spinning, more d) spinning, weaving, fewer 3. For most of the period of the Industrial Revolution, the majority of industrial power was supplied by a) water and wind. b) steam and wind. c) water and steam. 4. During the Industrial Revolution, the best Chemists were trained in a) Italy b) Germany c) United States d) Sweden e) Great Britain 5. During the Industrial Revolution, the cost of producing sulfuric acid greatly improved by a) replacing lead containers with glass containers b) replacing iron containers with glass containers c) replacing glass containers with lead containers d) replacing glass containers with iron containers 6. According to Wikipedia, the first large machine tool was used to a) plane rails for railroads b) drill coal mines c) shape plates for ship hulls d) bore cylinders for steam engines steam engines. 7. The Miner's Friend a) transported miners b) pumped water c) was electrical lighting d) provided ventilation 8. Puddling involved a) the use of coke instead of coal greatly reduced the cost of producing pig iron b) the use of coke instead of coal and led to much strong iron c) stirring with a long rod and became much cheaper when steam engines replaced manual stirring d) stirring with a long rod and was never successfully mechanised. -

Steam Engine

Imagine: you are on the writing staff of Scientific America Magazine. Your team is going to write an article titled “Technology that changed the world, the top six most important inventions of the Industrial Age” It has already been decided that Iron, Steam Engines, Rail Roads, Internal Combustion Engines, The Factory System and the Telegraph will be the six featured technologies, the question of how to rank them remains. They should be ranked from most profound and lasting to least. You must defend your assigned technology to the group with the information you recorded below. After an open debate, your group must come to a consensus by ranking the technologies and providing a written justification for the order. Individual role: Steam Engine: Prove: How did this technology have a lasting and profound impact on our lives. Your argument: Supporting evidence: The History of Steam Engines Inventors: Thomas Savery, Thomas Newcomen, James Watt Thomas Savery (1650-1715) Thomas Savery was an English military engineer and inventor who in 1698, patented the first crude steam engine, based on Denis Papin's Digester or pressure cooker of 1679. Thomas Savery had been working on solving the problem of pumping water out of coal mines, his machine consisted of a closed vessel filled with water into which steam under pressure was introduced. This forced the water upwards and out of the mine shaft. Then a cold water sprinkler was used to condense the steam. This created a vacuum which sucked more water out of the mine shaft through a bottom valve. Thomas Savery later worked with Thomas Newcomen on the atmospheric steam engine. -

Bank of America

Bank of America From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search Not to be confused with First Bank of the United States, Second Bank of the United States, or Bank of United States. Bank of America Corporation Bank of America logo since January 1, 2002 - now Type Public company NYSE: BAC Dow Jones Industrial Average Traded as Component S&P 500 Component Industry Banking, Financial services Bank America Predecessor(s) NationsBank Founded 1998 (1904 as Bank of Italy)[1] Bank of America Corporate Center Headquarters 100 North Tryon Street Charlotte, North Carolina, U.S. Area served Worldwide Charles O. Holliday (Chairman) Key people Brian T. Moynihan (President & CEO) Credit cards, consumer banking, corporate banking, finance and Products insurance, investment banking, mortgage loans, private banking, private equity, wealth management Revenue US$ 83.33 billion (2012)[2] Operating US$ 3.072 billion (2012)[2] income [2] Net income US$ 4.188 billion (2012) [2] Total assets US$ 2.209 trillion (2012) [2] Total equity US$ 236.95 billion (2012) Employees 272,600 (2012)[2] Bank of America Home Loans, Divisions Bank of America Merrill Lynch Merrill Lynch, U.S. Trust Subsidiaries Corporation Website BankofAmerica.com References: [3] Bank of America Corporation (NYSE: BAC) is an American multinational banking and financial services corporation headquartered in Charlotte, North Carolina. It is the second largest bank holding company in the United States by assets.[4] As of 2010, Bank of America is the fifth- largest company in the United States by total revenue,[5] and the third-largest non-oil company in the U.S. -

Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT

Los Angeles Department of City Planning RECOMMENDATION REPORT CULTURAL HERITAGE COMMISSION CASE NO.: CHC -2008 -43 94 -HCM HEARING DATE: November 6, 2008 Location: 1572 W. Sunset Blvd. TIME: 10:00 AM Council District: 1 PLACE : City Hall, Room 1010 Community Plan Area: Silverlake-Echo Park- 200 N. Spring Street Elysian Valley Los Angeles, CA Area Planning Commission: East Los Angeles 90012 Neighborhood Council: Greater Echo Park Elysian Legal Description: Lot FR 13 of Block 1, South Part of the Montana Tract PROJECT: Historic-Cultural Monument Application for the BANK OF AMERICA -ECHO PARK BRANCH REQUEST: Declare the property a Historic-Cultural Monument OWNER: Merchants National Realty Corporation Corporate Real Estate Assets 101 N. Tryon Street Charlotte, NC 28522 APPLICANT: Echo Park Historical Society APPLICANT’S Charles J. Fisher REPRESENATIVE: 140 S. Avenue 57 Los Angeles, CA 90042 RECOMMENDATION That the Cultural Heritage Commission: 1. Take the property under consideration as a Historic-Cultural Monument per Los Angeles Administrative Code Chapter 9, Division 22, Article 1, Section 22.171.10 because the application and accompanying photo documentation do not suggest the submittal may warrant further investigation. 2. Adopt the report findings. S. GAIL GOLDBERG, AICP Director of Planning [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] Ken Bernstein, AICP, Manager Office of Historic Resources Prepared by: [SIGNED ORIGINAL IN FILE] ________________________ Edgar Garcia, Preservation Planner Office of Historic Resources Attachments: August 28, 2008 Historic-Cultural Monument Application ZIMAS Report Bank of America- Echo Park Branch CHC-2008-4394-HCM Page 2 of 2 SUMMARY Built in 1908 and extensively remodeled in 1926, this one-story commercial building exhibits character-defining features of Beaux-Arts style architecture.