The Boy from Burnbank

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cardiff Council Cyngor Caerdydd Executive

CARDIFF COUNCIL CYNGOR CAERDYDD EXECUTIVE BUSINESS MEETING: 3 NOVEMBER 2011 WORLD BOXING CONVENTION 2013 (WBC) REPORT OF CHIEF OFFICER (CITY DEVELOPMENT) AGENDA ITEM: 11 PORTFOLIO : TRANSPORT & ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT Reason for this Report 1. To enable Cardiff to host the World Boxing Council Convention 2013 and approve appropriate budgets to assist in developing the event programme. 2. To attract a World Title bout and Convention which will have an economic impact of up to £3.2m in the city economy 3. To enhance Cardiff’s reputation as an international sports capital and to generate significant global media exposure to promote the city on an international stage. Background 4. Over the last decade Cardiff has built an international reputation for the successful delivery of high profile sporting events, including; the Rugby World Cup; the FA Cup and Heineken Cup Finals, the Ashes Test and the Ryder Cup. Alongside this the city has developed a world-class sporting and visitor destination infrastructure. In recognition of this Cardiff was recently awarded the status of European Capital of Sport. 5. It is recognised that this programme of major sporting events has led to significant benefits for the city economy, including: attracting tourists and the additional consumer spend they bring into the local economy; world- wide media coverage and profile; increased civic and national pride and encouraging increased participation in sporting activities. 6. The World Boxing Council Night of the Champions and World Boxing Convention therefore represent significant opportunities for Cardiff to build on its established platform and to expand into a new events market, with the ultimate aim of becoming a recognised location for major boxing events. -

Wbc´S Lightweight World Champions

WORLD BOXING COUNCIL Jose Sulaimán WBC HONORARY POSTHUMOUS LIFETIME PRESIDENT (+) Mauricio Sulaimán WBC PRESIDENT WBC STATS WBC FLYWEIGHT CHAMPIONSHIP BOUT ARIAKE COLOSSEUM / TOKYO, JAPAN MARCH 20, 2017 THIS WILL BE WBC’S 1, 968 CHAMPIONSHIP TITLE FIGHT IN THE 54 YEARS HISTORY OF THE WBC AKIHIKO HONDA & TEIKEN BOXING PROMOTIONS, PRESENTS: JUAN HERNANDEZ DAIGO HIGA (MEXICO) (JAPAN) WBC CHAMPION WBC OFFICIAL CHALLENGER DATE OF BIRTH: FEBRUARY 24, 1987 DATE OF BIRTH: AUGUST 9, 1995 PLACE OF BIRTH: COAHUITLAN, VERACRUZ PLACE OF BIRTH: URASOE, JAPAN AGE: 30 AGE: 21 RESIDES: MEXICO CITY RESIDES: TOKYO, JAPAN ALIAS: CHURRITOS ALIAS: PROF. RECORD: 34-2-0, 25 KO’S PROF. RECORD: 12-0-0, 12 KO’S GUARD: ORTHODOX GUARD: ORTHODOX TOTAL ROUNDS: 144 TOTAL ROUNDS: 42 WBC TITLES FIGHTS: 2 (1-1-0) WBC TITLES: YOUTH / OPBF MANAGER: ISAAC BUSTOS MANAGER: AKIHIKO HONDA ALJ PROMOTER: PROMOCIONES DEL PUEBLO PROMOTER: TEIKEN BOXING PROMOTIONS WBC´S FLYWEIGHT WORLD CHAMPIONS NAME PERIODO CHAMPION 1. PONE KINGPETCH (THA) 1963 2. HIROYUKI EBIHARA (JAP) 1963 - 1964 3. PONE KINGPETCH (THA) * 1964 - 1965 4. SALVATORE BURRUNI (ITALY) 1965 - 1966 5. WALTER MCGOWAN (GB) 1966 6. CHARTCHAI CHIONOI (THA) 1966 - 1969 7. EFREN TORRES (MEX) 1969 - 1970 8. CHARTCHAI CHIONOI (THA) * 1970 9. ERBITO SALAVARRIA (PHIL) 1970 - 1971 10. BETULIO GONZALEZ (VEN) 1972 11. VENICE BORKORSOR (THA) 1972 - 1973 12. BETULIO GONZALEZ (VEN) * 1973 - 1974 13. SHOJI OGUMA (JAP) 1974 - 1975 14. MIGUEL CANTO (MEX) 1975 - 1979 15. CHAN-HEE PARK (KOR) 1979 - 1980 16. SHOJI OGUMA (JAPAN) * 1980 - 1981 17. ANTONIO AVELAR (MEX) 1981 - 1982 18. PRUDENCIO CARDONA (COL) 1982 19. -

26727 Consignor Auction Catalogue Template

Auction of Important Canadian & International Art September 24, 2020 AUCTION OF IMPORTANT CANADIAN & INTERNATIONAL ART LIVE AUCTION THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 24TH AT 7:00 PM ROYAL ONTARIO MUSEUM 100 Queen’s Park (Queen’s Park at Bloor Street) Toronto, Ontario ON VIEW Please note: Viewings will be by appointment. Please contact our team or visit our website to arrange a viewing. COWLEY ABBOTT GALLERY 326 Dundas Street West, Toronto, Ontario JULY 8TH - SEPTEMBER 4TH Monday to Friday: 9:00 am to 5:00 pm SEPTEMBER 8TH - 24TH Monday to Friday: 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Saturdays: 11:00 am to 5:00 pm Sunday, September 20th: 11:00 am to 5:00 pm 326 Dundas Street West (across the street from the Art Gallery of Ontario) Toronto, Ontario M5T 1G5 416-479-9703 | 1-866-931-8415 (toll free) | [email protected] 2 COWLEY ABBOTT | September Auction 2020 Cowley Abbott Fine Art was founded as Consignor Canadian Fine Art in August 2013 as an innovative partnership within the Canadian Art industry between Rob Cowley, Lydia Abbott and Ryan Mayberry. In response to the changing landscape of the Canadian art market and art collecting practices, the frm acts to bridge the services of a retail gallery and auction business, specializing in consultation, valuation and professional presentation of Canadian art. Cowley Abbott has rapidly grown to be a leader in today’s competitive Canadian auction industry, holding semi-annual live auctions, as well as monthly online Canadian and International art auctions. Our frm also ofers services for private sales, charity auctions and formal appraisal services, including insurance, probate and donation. -

Castle Cinema Merthyr Tydfil

Archaeology Wales Castle Cinema Merthyr Tydfil Archaeological Watching Brief By Adrian Hadley & Chris E Smith Report No. 1134 Archaeology Wales Limited, Rhos Helyg, Cwm Belan, Llanidloes, Powys, SY18 6QF Tel: +44 (0) 1686 440371 Email: [email protected] Archaeology Wales Castle Cinema, Merthyr Tydfil Archaeological Watching Brief Prepared For: Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council Edited by: Authorised by: Signed: Signed: Position: Position: Date: Date: By Adrian Hadley & Chris E Smith Report No: 1134 Date: June 2013 Archaeology Wales Limited, Rhos Helyg, Cwm Belan, Llanidloes, Powys, SY18 6QF Tel: +44 (0) 1686 440371 Email: [email protected] CONTENTS 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Location and scope of work .......................................................................................... 1 1.2 Geology and topography ............................................................................................... 1 1.3 Archaeological and Historical Background .................................................................. 2 2 Aims and Objectives ............................................................................................................. 3 2.1 Watching Brief .............................................................................................................. 3 3 Methodology ........................................................................................................................ -

Jackie Brown (Manchester)

© www.boxinghistory.org.uk - all rights reserved This page has been brought to you by www.boxinghistory.org.uk Click on the image above to visit our site Jackie Brown (Manchester) Active: 1925-1939 Weight classes fought in: fly, bantam Recorded fights: 138 contests (won: 105 lost: 24 drew: 9) Born: 29th November 1909 Died: 5th March 1971 Manager: Harry Fleming Fight Record 1925 May 18 Harry Gainey (Gorton) WPTS(6) Arena, Collyhurst Source: Harold Alderman (Boxing Historian) 1926 Mar 23 Dick Manning (Manchester) WPTS(6) Free Trade Hall, Manchester Source: Boxing 31/03/1926 page 126 1927 Mar 5 Tommy Brown (Salford) LPTS(10) Sussex Street Club, Salford Source: Boxing 09/03/1927 page 44 Mar 8 Billy Cahill (Openshaw) WKO6 Free Trade Hall, Manchester Source: Vic Hardwicke (Boxing Historian) Promoter: Jack Smith Mar 15 Freddie Webb (Salford) LRSF3(3) Free Trade Hall, Manchester Source: Boxing 23/03/1927 page 75 (7st 10lbs competition) Promoter: Jack Smith May 15 Ernie Hendricks (Salford) DRAW(10) Adelphi Club, Salford Source: Boxing 18/05/1927 page 218 Jul 7 Young Fagill (Liverpool) WDSQ1(6) Pudsey Street Stadium, Liverpool Source: Boxing 12/07/1927 page 401 Match made at 8st 4lbs Referee: WJ Farnell Sep 27 Joe Fleming (Rochdale) WPTS(6) Free Trade Hall, Manchester Source: Boxing 04/10/1927 page 152 Promoter: Jack Smith Oct 7 Harry Yates (Ashton) WPTS(10) Ashbury Hall, Openshaw Source: Boxing 11/10/1927 page 173 Nov 4 Freddie Webb (Salford) WPTS(10) Ashbury Hall, Openshaw Source: Boxing 08/11/1927 page 235 Nov 18 Jack Cantwell (Gilfach Goch) -

Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity

Copyright By Omar Gonzalez 2019 A History of Violence, Masculinity, and Nationalism: Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity By Omar Gonzalez, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the Department of History California State University Bakersfield In Partial Fulfillment for the Degree of Master of Arts in History 2019 A Historyof Violence, Masculinity, and Nationalism: Pugilistic Death and the Intricacies of Fighting Identity By Omar Gonzalez This thesishas beenacce ted on behalf of theDepartment of History by their supervisory CommitteeChair 6 Kate Mulry, PhD Cliona Murphy, PhD DEDICATION To my wife Berenice Luna Gonzalez, for her love and patience. To my family, my mother Belen and father Jose who have given me the love and support I needed during my academic career. Their efforts to raise a good man motivates me every day. To my sister Diana, who has grown to be a smart and incredible young woman. To my brother Mario, whose kindness reaches the highest peaks of the Sierra Nevada and who has been an inspiration in my life. And to my twin brother Miguel, his incredible support, his wisdom, and his kindness have not only guided my life but have inspired my journey as a historian. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This thesis is a result of over two years of research during my time at CSU Bakersfield. First and foremost, I owe my appreciation to Dr. Stephen D. Allen, who has guided me through my challenging years as a graduate student. Since our first encounter in the fall of 2016, his knowledge of history, including Mexican boxing, has enhanced my understanding of Latin American History, especially Modern Mexico. -

Boxing Edition

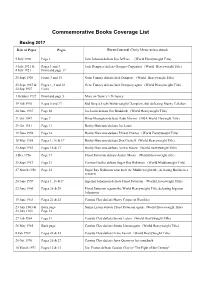

Commemorative Books Coverage List Boxing 2017 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 5 July 1910 Page 3 Jack Johnson defeats Jim Jeffries (World Heavyweight Title) 3 July 1921 & Pages 1 and 3 Jack Dempsey defeats Georges Carpentier (World Heavyweight Title) 4 July 1921 Front and page 17 25 Sept 1926 Front, 3 and 15 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1927 & Pages 1, 3 and 18 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey again (World Heavyweight Title) 24 Sep 1927 Front 1 October 1927 Front and page 5 More on Tunney v Dempsey 19 Feb 1930 Pages 5 and 22 Kid Berg is Light Welterweight Champion after defeating Mushy Callahan 24 June 1937 Page 30 Joe Louis defeats Jim Braddock (World Heavyweight Title) 21 Oct 1947 Page 7 Rinty Monaghan defeats Dado Marino (NBA World Flyweight Title) 29 Oct 1951 Page 11 Rocky Marciano defeats Joe Louis 19 June 1954 Page 14 Rocky Marciano defeats Ezzard Charles (World Heavyweight Title) 18 May 1955 Pages 1, 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Don Cockell (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1955 Pages 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight Title) 3 Dec 1956 Page 17 Floyd Patterson defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight title) 25 Sept 1957 Page 23 Carmen Basilio defeats Sugar Ray Robinson (World Middleweight Title) 27 March 1958 Page 23 Sugar Ray Robinson wins back the Middleweight title, defeating Basilio in a rematch 28 June 1959 Pages 1, 16 &17 Ingemar Johansson defeats Floyd Patterson (World Heavyweight Title) 22 June 1960 Pages 28 & 29 Floyd Patterson -

A/03/49 W. Howard Robinson: Collection

A/03/49 W. Howard Robinson: Collection Lewisham Local History and Archives Centre Lewisham Library, 199-201 Lewisham High Street, London SE13 6LG The following items were received from Mrs Gillian Lindsay: Introduction W. (William) Howard Robinson was a noted representative artist and portrait painter of the early twentieth century. He was born on 3 November 1864 in Inverness-shire and attended Dulwich College from 1876 to 1882. He followed his father, William Robinson, into the Law and after a brief legal career studied Art at the Slade School under Sir Simeon Solomon. His professional career as a portrait painter began circa 1910 when his interest in the sport of fencing led him to sketch all the leading fencers of the day, these sketches were reproduced in the sporting publication “The Field” leading to further commissions for portraits with a sporting theme. He became well-known for his sketches and portraits of figures in the sporting world such as Lord Lonsdale, Chairman of the National Sporting Club. His two best known paintings were “An Evening at the National Sporting Club” (1918) and “A Welsh Victory at the National Sporting Club” (1922). This first painting was of the boxing match between Jim Driscoll and Joe Bowker, it took Robinson four years to complete and contained details of 329 sporting celebrities. The second painting commemorated the historic boxing match between Jimmy Wilde and Joe Lynch that took place on 31 March 1919 and shows the Prince of Wales entering the ring to congratulate the victor, the first time that a member of the royal family had done so. -

Pacific Citizen) with the Enemy Act

New eligibility rules in effect for JACL keg meet PACIFIC · -:CITIZEN LOS ANGELES-Entry fOl'm ~ 1'ournament enl!'ies must be M.mbmhlP Publication: Japan". Am"ltln CIII, ..s ~'"". 125 Wtillr 51.. L.. l"'l.I ... Ca 90012 (213) MA 6·4471 (or the 21.t nnnual Nallonal certified 8S to JACL member· Publlsh.d Woolly Empt ~ ..t Wook of th. Y• ., ,- s...~ Clm P.. ",. ',Id at Los Ant.I .., Calif, IN THIS ISSUE JACL Nisei Bowling Tourna· ship and o[(leial league aver· ment arc due Monday. J"n. ages by the localochapter pres· '" CENERAL NEWS Vol. 64 No. 2 FRIDAY, JANUARY 13, 1967 Edit/Bus. Office: MA 6-6936 CaUfornl. brit't ~ 'oqutn\ In plud~ 23. tournament chairman Easy idant or member of the Na· TEN CENTS t"1 for yen claims cue before Fujimoto reminded today. tlonal JACL Advisory Board U.S, Supreme Court: L.A "0" ttN to decide on evacuee pcn· Entry fees must accompany on Bowling, $lon c~U •...••.. 1 aU entries willl checks made AU bowlers will be dlecked payabte to YD S Mlnamide. for ABC. W10C and J ACL NATIONAL~ACL '" Ty New ellclbllt~ · rules clfcell\ e for troosurer. and maUed to membership cards at time 01 1967 J ACL Nat.'1 Nisei bowlinE Kajimoto. 1246 Gardena Blvd .• registration. tournament.: Nat.'l JACL Credo· Gardena. C<lli!. 90247. Enterinr Avera,.. 1\ Union dtCl8ff.S 5 pel • 1 Calif. brief eloquent in pleading SJ'A :!O CommlHt't celtbrates vic· Entry forms lor mcn's and P articipants in each event lor~' In StaHle , ..•...... -

Theboxing Biographies Newsletter Volume3 - No 11 25Th Dec, 2008

1 TheBoxing Biographies Newsletter Volume3 - No 11 25th DEc, 2008 www.boxingbiographies.com If you wish to receive future newsletters ( which includes the images ) please email the message “NEWS LETTER” [email protected] The newsletter is also available as a word doc on request As always the full versions of these articles are on the website My very best wishes to all my readers and thank you for the continued support you have given which I do appreciate a great deal. Name: Willie Pastrano Career Record: click Birth Name: Wilfred Raleigh Pastrano Nationality: US American Hometown: New Orleans, Louisiana, USA Born: 1935-11-27 Died: 1997-12-06 Age at Death: 62 Stance: Orthodox Height: 6′ 0″ Trainers: Angelo Dundee & Whitey Esneault Manager: Whitey Esneault Wilfred Raleigh Pastrano was born in the Vieux Carrê district of New Orleans, Louisiana, on 27 November 1935. He had a hard upbringing, under the gaze of a strict father who threatened him with the belt if he caught him backing off from a confrontation. 'I used to run from fights,' he told American writer Peter Heller in 1970. 'And papa would see it from the steps. He'd take his belt, he'd say "All right, me or him?" and I'd go beat the kid: His father worked wherever and whenever he could, in shipyards and factories, sometimes as a welder, sometimes as a carpenter. 'I remember nine dollars a week paychecks,' the youngster recalled. 'Me, my mother, my step-brother, and my father and whatever hangers-on there were...there were always floaters in the family.' Pastrano was an overweight child but, like millions of youngsters at the time, he wanted to be a sports star like baseball's Babe Ruth. -

Pari USA E Australia

*Jy II..I—. ^i'|i »-n • yi> •• IP l « i I •*'(• l'Utlìtd / •«boto. 26 settembre, 1964 PAG. 9/sport If Alle ore 20,30 a Madrid i neroazzurri affrontano l'Indepe ridiente per la Coppa dei campióni Intei* « mondiale » ? <. Giudice ed Herrera nei guai, per le formazioni - Tra i nerazzurri INTER . assenti sicuri Burgnich e Jair; probabilmente anche Mazzola 1 CORSO BERNAO dovrà da re. « forfait » - Giocheranno forse Malatrasi a terzino, PICCHI PAFLIK Tagnin a mediano, Domenghini all'ala e Peirò interno . SUAREZ • • MURA ' FACCUETTI GUZMAN 8AIITI GUARNEKI MILANI (tò SUAREZ MALDONADO , SANTORO IMA LATRASI DECARIA '• (PEIRO*) MAZZOLA RODRIGUEZ i TAGNIN ACEVEDO DOMENGHINI SAVOY ARBITRO: ORTIZ (Spagna) INDEPENDIENTE ottimisti un'ala destra, perciò ecco che Dai nostro inviato mi si affaccia la tentazione di MADRID. 25 riforrere a Domenghmi. Que Ne 16,10 dall'aeroporto di Fiumicino Alla vigilia dello storico -spa st'ultimo mi tornerebbe utilissi reggio' per l'assegnazione del mo perche sa anche retroce titolo mondiale, che domani al dere e dar man forte al centro lo stadio • Chamartin - richia campo Non dimenticate che al merà non meno di centomila l'Inter bista un part'^io- sono spettatori (dati anche i prezzi loro -.t (volta, clip debbono vin molto accessibili), grossi pro cere •- blemi angustiano sia Herrera - Ma — diciamo — se Mazzo che Giudice. I due - condottie la dovesse, malauguratamente, ri » non hanno ancora deciso essere indisponibile, il proble le rispettive formazioni, riser ma dell'attacco rimarrebbe sem Oggi gli azzurri partono vandosi di diramarle poche ore plificato .. ». prima del match. « Appunto — inculca II II Giudice ha i nervi a fior di — in tal caso, Li soluzione sa pelle. -

Name: Ken Buchanan Career Record: Click Nationality: British

Name: Ken Buchanan Career Record: click Nationality: British Birthplace: Edinburgh, Scotland Hometown: Edinburgh, Scotland, United Kingdom Born: 1945-06-28 Stance: Orthodox Height: 5′ 7½″ Reach: 178 Manager: Eddie Thomas Trainer: Gil Clancy 1965 ABA featherweight champion International Boxing Hall of Fame Bio Further Reading: The Tartan Legend: The Autobiography http://www.stv.tv/info/sportExclusive/20070618/Ken_Buchanan_interview_180607 Ken Buchanan was born in Edinburgh, Scotland, on 28 June 1945, to p a r e n t s Tommy and Cathie. both of whom were very supportive of their son's sporting ambitions throughout his early life. However, it wa s Ken's aunt, Joan and Agnes, who initially encouraged the youngster's enthusiasm for boxing. In 1952. the pair were shopping for Christmas presents for Ken and his cousin. Robert Barr. when they saw a pair of boxing gloves and it occurred to them that the two boys often enjoyed some playful sparring together. So. at the age of seven, the young Buchanan received his first pair of boxing gloves. It was another casual act, this time by father Tommy that sparked young Ken's interest in competitive boxing. One Saturday, when the family had finished shopping, Tommy took his son to the cinema to see The Joe Louis Story and Ken decided he'd like to join a boxing club. Tommy agreed. and the eight-year-old joined one of Scotland's best clubs. the Sparta. Two nights a week, alongside 50 other youths, young Ken learned how to box and before long he had won his first medal – with a three-round points win in the boys' 49lb (three stone seven pound) division.