How Sandra Day O'connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ELEANOR ROOSEVELT How the Former U.S

MILESTONES Remembering ELEANOR ROOSEVELT How the former U.S. First Lady paved the way for women’s independence ormer First Lady Eleanor the longest serving First Lady. Roosevelt was a tireless Eleanor leveraged her position advocate for women and to ensure that women, youth, and social justice, and left an those living in poverty or at the Findelible mark on society. margins of society had opportuni- Eleanor was born on October ties to enjoy a peaceful, equitable 11, 1884 in Manhattan, New York, and comfortable life—regard- into a family that was part of the less of colour, age, background New York establishment. She lost or discrimination on any other both her parents by the age of 10 grounds. She raised awareness and was raised by relatives until the and shared her beliefs in her daily age of 15. She attended Allenswood syndicated newspaper column, My Boarding Academy, a finishing Day, which she established in 1935 school in Wimbledon, England, and continued until her death.1 from 1899 to 1902. The head- In 1935, in the midst of a Great mistress, Marie Souvestre, was an Depression that saw youth unem- educator who sought to cultivate ployment rise to 30%, Eleanor independence and social responsi- Original painting by Gillian Goerz advocated strongly for govern- bility in young women. She took a ment intervention. In response, special interest in Roosevelt, who the National Youth Administration flourished under her leadership.1 At 18, Eleanor was summoned (NYA) was established to focus on providing work and education home to New York City by her grandmother to make her social for Americans between the ages of 16 and 25.3 debut. -

Ford, Betty - Biography” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 37, folder “Ford, Betty - Biography” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 37 of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library NOTES ON MRS • FORD March 18, 1975 $ tt c. UCS. ~o o ~ D Mrs. Ford's father died when she was 16 years old. When she was 21 her mother married Arthur M. Godwin. Mr. Godwin had been a friend of both Mrs. Ford's mother and father. In 1948 Mrs. Ford's mother had a heart attack and died. Mr. Godwin married a woman by the name of Lil in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Mr. Godwin had been married prior to his marriage to Mrs. Ford's mother. His first wife was killed in Mexico in 1936 in an automobile accident. Mr. Godwin was with her. Mrs. Ford's first husband was William c. -

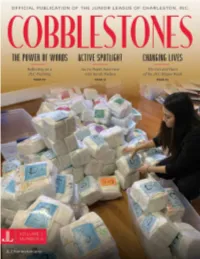

Cobblestones

COBBLESTONES Cobblestones is a member-driven, TABLE OF mission-focused publication that highlights the Junior League of Charleston—both its members and its community partners—through CONTENTS engaging stories using quality design and photography. LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT 5 JLC TRAINING EDITOR + PRINT PUBLICATION COMMITTEE CHAIR: EDUCATION Casey Vigrass 975 Savannah HWY Suite #105 (843) 212-5656 [email protected] 10 PRINT PUBLICATION COMMITTEE 12 PROVISIONAL SPOTLIGHT ASSISTANT CHAIR: Liz Morris SUSTAINER SPOTLIGHT 13 PRINT PUBLICATION COMMITTEE: Lizzie Cook PRESIDENT SPOTLIGHT Ali Fox 17 Catherine Korizno GIVING BACK DESIGN + ART DIRECTION: 20 06 Brian Zimmerman, Zizzle WOMEN'S SUFFERAGE ACTIVE SPOTLIGHT: COVER IMAGE: SARAH NIELSEN Featuring Alle Farrell 14 Restore. Do More. CHARLESTON RECEIPTS 18 Cryotherapy Whole Body Facials Local CryoSkin Slimming Toning Facials 08 Infrared Sauna IV Drip Therapy The Forward- Thinking Mindset Photobiomodulation (PBM) IM Shots of a Junior League Founder Stretch Therapy Micronutrient Testing DIAPER BANK Compression Therapy Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy Book your next event with us! 26 24 VOLUME 1 | NUMBER 6 3 FROM THE EDITOR FROM THE PRESIDENT “We have the responsibility to act and the opportunity to conscientiously act to affect Passionate. Hard-working. Unstoppable. the environment around us.” – Mary Harriman Rumsey, Founder of the Junior League These words, spoken about the Junior League of Charleston, have described our Recently, I was blessed by the opportunity to attend Organizational Development -

Membership Community Impact the Junior League

THE JUNIOR LEAGUE: MEMBERSHIP VOLUNTEER POWERHOUSE The JLPA•MP invites women over the age of 21 of all backgrounds including, but not limited to, race, national origin, ethnicity, In 1901, 19-year-old Mary Harriman founds the socioeconomic status, religion/beliefs, ability and sexual orientation first Junior League in New York City, envisioning an who demonstrate an interest in and commitment to voluntarism organization where women could volunteer their to join our League. The JLPA•MP understands that the impact and time, develop their skills and improve the lives of integrity of our work will thrive when our members can express their those in their communities. whole selves while living our mission. We are committed to inclusive Today Junior Leagues in 291 COMMUNITIES environments of diverse individuals, organizations and communities. throughout Canada, Mexico, the United Kingdom and the United States continue to provide opportunities for women who are COMMUNITY ImPACT committed to honing their leadership skills by tackling the issues that confront their region. Empowering girls to be STEAM leaders of tomorrow. SINCE 1965, the Junior League of Palo Alto•Mid Peninsula The League’s Done in a Day projects focus on short, intensive (JLPA•MP) has supported more than 94 community service projects, community activities that are typically completed in a single day awarded community grants to nearly 200 area nonprofits and or weekend. Recent project partners include My New Red Shoes, contributed thousands of volunteer hours to our community. Rebuilding Together Peninsula, The Princess Project and Second Harvest Food Bank. OUR MISSION Project STEAM, a program under Project READ Redwood City, The Junior League of Palo Alto•Mid Peninsula, Inc. -

SYLLABUS the ROBERTS COURT – from BAD to WORSE 1. INTRODUCTION I Went to Law School When the Decisions of the “Liberal” Su

SYLLABUS THE ROBERTS COURT – FROM BAD TO WORSE 1. INTRODUCTION I went to law school when the decisions of the “liberal” Supreme Court presided over by Chief Justice Earl Warren defined what our Constitution meant – an end to “separate but equal”, limits on police power, the right to a lawyer even if you couldn’t afford one, separation of Church and State, ‘one man, one vote’ – the list goes on and on. These decisions are in fact why I went to law school, with the fantasy of fighting for justice, truth, and the American Way….as the Warren Court had defined it. But I instead have lived a professional lifetime under the Burger Court, the Rehnquist Court, and most awful of all, the Roberts Court of the last 15 years – a Court that seems determined to turn our Constitutional clock back to pre-New Deal, if not further. From 2011, when Republicans gained control of the House of Representatives, until the present, Congress has enacted hardly any major legislation outside of the tax law President Trump signed in 2017. In the same period, the Supreme Court dismantled much of America's campaign finance law, severely weakened the Voting Rights Act, permitted states to opt-out of the Affordable Care Act's Medicaid expansion, weakened laws protecting against age discrimination and sexual and racial harassment, gave corporations control over much of our economy, but held that every state must permit same-sex couples to marry. This powerful unelected body, now controlled by six very conservative Republicans, has become and will continue to be the locus of policymaking in the United States. -

HISTORY Page PAST COMMUNITY PROJECTS

HISTORY Page PAST COMMUNITY PROJECTS ..................................................... C-2 PROFITS OF FUNDRAISERS ......................................................... C-10 PAST PRESIDENTS......................................................................... C-15 HELEN KLAMER PHILP AWARD ................................................ C-18 MEG DETTWILER MEMORIAL SCHOLARSHIP ....................... C-20 COMMUNITY VOLUNTEER OF THE YEAR AWARD .............. C-22 MARY HARRIMAN PRESIDENT’S AWARD ............................ C-123 SUSTAINER ADVISORY COMMITTEE ....................................... C-24 HISTORY OF AJLI .......................................................................... C-25 HISTORY OF JLE ............................................................................ C-26 1920’s ................................................................................................ C-26 1930’s ................................................................................................ C-26 1940’s ................................................................................................ C-26 1950’s ................................................................................................ C-26 1960’s ................................................................................................ C-27 1970’s ................................................................................................ C-28 1980’s ............................................................................................... -

How Sandra Day O'connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg Went to the Supreme Court and Changed the World

Yeshiva University, Cardozo School of Law LARC @ Cardozo Law Cardozo News 2016 Cardozo News 4-26-2016 Sisters in Law- How Sandra Day O'Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg Went to the Supreme Court and Changed the World Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://larc.cardozo.yu.edu/cardozo-news-2016 Recommended Citation Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, "Sisters in Law- How Sandra Day O'Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg Went to the Supreme Court and Changed the World" (2016). Cardozo News 2016. 9. https://larc.cardozo.yu.edu/cardozo-news-2016/9 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Cardozo News at LARC @ Cardozo Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cardozo News 2016 by an authorized administrator of LARC @ Cardozo Law. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Sisters in Law: How Sandra Day O'Connor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg We... https://cardozo.yu.edu/news/sisters-law-how-sandra-day-oconnor-and-ru... SISTERS IN LAW: HOW SANDRA DAY O'CONNOR AND RUTH BADER GINSBURG WENT TO THE SUPREME COURT AND CHANGED THE WORLD RELATED NEWS August 16, 2019 Cardozo Welcomes the J.D. Class of 2022 (/news/cardozo- welcomes-jd- class-2022) Integrity, generosity, grit and joy were the guiding themes of Dean Melanie Leslie’s welcome to the Class of 2022 for their first day of orientation. July 24, 2019 Professor Alex Reinert Named Max Freund Professor of Litigation April 26, 2016 & Advocacy (/news /professor-alex- April 18, 2016 - Students and faculty joined Linda Hirshman, author reinert-named-max- of the best-selling book Sisters in Law: How Sandra Day O'Connor and freund-professor- litigation-advocacy) Ruth Bader Ginsburg Went to the Supreme Court and Changed the Professor Alexander World, for a fun and informative conversation about these two Reinert has been named the Max Freund monumental justices. -

Junior League of Washington Christmas Shop Luncheon” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 4, folder “10/16/75 - Junior League of Washington Christmas Shop Luncheon” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Betty Ford donated to the United States of America her copyrights in all of her unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. THE WHITE H OUSE WASHINGTON October 6, 1975 MEMORANDUM TO: PETER SORUM \ FROM : su;~N PORTER SUBJECT : Action Memo Mrs . Ford has accepted the following out-of-house invitation: EVENT : Christmas Shop Luncheon GROUP : Junior League of Washington DATE : Thursday , October 16 , 1975 TIME: 12:00 noon Doors open; drinks 12 : 30 p.m. Luncheon begins PLACE : Madison Hotel Washington , D. C . CONTACT : Mrs . William Bryant , Luncheon Chairman 356- 9612 (Mrs . John Forstmann, Christmas Shop Chairman, 365-1593) CMrs. Robert Dudley , Chairman , Patrons Committee, 363-588§) COMMENTS : The annual Junior League Christmas Shop begins with a Champagne Preview Opening the evening of Tuesday, October 14th and is followed by a luncheon each of the three following days , October 15, 16 and 17. -

Happy Birthday to Ajli Founder Mary Harriman!

E - I NA PUBLICATION OF THESJUNIOR LEAGUEIOF PASADENAG, INC. H T HAPPY BIRTHDAY TO AJLI FOUNDER MARY HARRIMAN! November, 2008, No. 3 E-Insight Mary Harriman Rumsey was born in New York on November 17, 1881. In NEXT GENERAL 1901, at the age of 19, she founded MEMBERSHIP MEETING the Junior League for Promotion of NOVEMBER 25, 2008 the Settlement Movement in New 6:30 P.M. DINNER/ SOCIAL York (now the Junior League). She is 7:00 P.M. MEETING also credited with opening approxi- mately 500 playgrounds in New York ARMORY CENTER FOR THE ARTS City, and in helping to organize the 145 N. RAYMOND AVENUE Farm Foundation in1933. PASADENA, CA UPCOMING DATES In 1901, Mary Harriman, a 19-year-old New York City debutante with SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 2ND a social conscience, formed the Junior League for the Promotion of SAVOR THE FLAVOR COOKBOOK EVENT Settlement Movements. Harriman mobilized a group of 80 other THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 20 young women, hence the name "Junior" League, to work to improve JACOB MAARSE HOLIDAY EVENT child health, nutrition and literacy among immigrants living on the PASSPORT TO PASADENA KICKOFF Lower East Side of Manhattan. Inspired by her friend Mary, Eleanor NOVEMBER 21-DECEMBER 7 PASSPORT TO PASADENA Roosevelt joins the Junior League of the City of New York in 1903, SHOPPING DAYS teaching calisthenics and dancing to young girls at the College FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 7 Settlement House. “ASANTI FINE JEWELLERSTRUNK SHOW” In 2008, Mary’s vision lives on. Formed in 1921, AJLI provides con- THURSDAY, DECEMBER 11 tinuity and support, guidance and leadership development opportuni- GARDEN CLUB HOLIDAY PARTY ties to 292 Junior Leagues in Canada, Mexico, the United Kingdom JUNIOR LEAGUE OF PASADENA, INC. -

President's Message

Fall 2016 Newsletter Junior League of Eau Claire Leadership Team President: Courtney Kanz President-Elect: Sue Mertens Past President: Katie Walk Secretary: Leslie Lyons Treasurer: Amy Weiss PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Well, it’s here – summer is over, the kids are back to school, the days are getting shorter and shorter. I don’t know about all of you but my summer went WAY too fast, as it always does. While I am not thrilled to be pulling my sweaters out of their hiding spot, I am really excited to officially start the 2016-2017 Junior League year! Our Fall Kick-off Event on September 15th at Florian Gardens was a huge success! In addition to fifteen existing members, we had ten potential new members in attendance to hear about the legacy of the Junior League of Eau Claire and how we have been transforming our community for over 85 years. If you were able to join us at the event, you also had an opportunity to hear about the Board’s strategy for the upcoming year. Our main focus is membership – growing, retaining and engaging our members. We have already implemented a few more visible components to this plan and you’re reading one of them right now! After a brief hiatus from publishing our newsletter I am excited that we are reviving it this year. These newsletters are a piece of history! It is so fun to pull out old newsletters and reflect on our past accomplishments. It is also an important connection point for all of our membership classes. -

In Honor of Sandra Day O'connor

BALES TRIBUTE 58 STAN. L. REV. 1705 5/12/2006 4:14:22 PM IN HONOR OF SANDRA DAY O’CONNOR JUSTICE SANDRA DAY O’CONNOR: NO INSURMOUNTABLE HURDLES Scott Bales* Sandra Day O’Connor has often said that, as “a cowgirl from Eastern Arizona,” she was as surprised as anyone when President Ronald Reagan nominated her in 1981 as the first woman to serve on the Supreme Court of the United States.1 Her surprise reflects her unassuming, down-to-earth manner. But O’Connor’s experiences as a cowgirl from Arizona and from serving in each branch of its state government—along with her ties to Stanford—were critical factors in her appointment. This same background, I believe, goes far to explain why, by the time of her 2006 retirement, she is regarded as the world’s most influential woman lawyer, both for her role on the Court and as a global spokesperson for judicial independence and the rule of law. O’Connor spent her childhood on her family’s Lazy B Ranch, which straddled the border of New Mexico and Arizona. The remote ranch—more than 200 miles southeast of Phoenix and about 200 miles northwest of El Paso—occupied almost 200,000 acres of sparse, arid land in the high Sonoran desert. “It was no country for sissies, then or now. Making a living there takes a great deal of hard work and considerable luck.”2 Much turned on the vagaries of weather and the livestock markets. Life on the cattle ranch was not easy, and when O’Connor was born the ranch house lacked indoor plumbing, electricity, and running water. -

The Journal of ACS Issue Briefs TABLE of CONTENTS

Advance The Journal of ACS Issue Briefs TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction The Troubling Turn in State Preemption: The Assault on Progressive Cities and How Cities Can Respond 3 Richard Briffault, Nestor Davidson, Paul A. Diller, Olatunde Johnson, and Richard C. Schragger Curbing Excessive Force: A Primer on Barriers to Police Accountability 23 Kami N. Chavis and Conor Degnan Access to Data Across Borders: The Critical Role for Congress to Play Now 45 Jennifer Daskal Expanding Voting Rights Through Local Law 59 Joshua A. Douglas Sex Discrimination Law and LGBT Equality 77 Katie R. Eyer Troubling Legislative Agendas: Leveraging Women’s Health Against Women’s Reproductive Rights 93 Michele Goodwin Coming to Terms with Term Limits: Fixing the Downward Spiral of Supreme Court Appointments 107 Kermit Roosevelt III and Ruth-Helen Vassilas A Pragmatic Approach to Challenging Felon Disenfranchisement Laws 121 Avner Shapiro The Bivens Term: Why the Supreme Court Should Reinvigorate Damages Suits Against Federal Officers 135 Stephen I. Vladeck Restoring the Balance Between Secrecy and Transparency: 143 The Prosecution of National Security Leaks Under the Espionage Act Christina E. Wells Parallel State Duties: Ninth Circuit Class Actions Premised on Violations of FDCA Reporting Requirements 159 Connor Karen ACS BOARD OF DIRECTORS Debo P. Adegbile David C. Frederick Ngozi Nezianya, Student Christina Beeler, Student Caroline Fredrickson, Board Member, Board Member, ACS President Northwestern University of Houston Ruben Garcia School of Law Law Center Nancy Gertner Ricki Seidman Nicole G. Berner Reuben A. Guttman Marc Seltzer Elise Boddie Keith M. Harper Cliff Sloan, Chair Timothy W. Burns Christopher Kang Dawn L.