In Honor of Sandra Day O'connor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ELEANOR ROOSEVELT How the Former U.S

MILESTONES Remembering ELEANOR ROOSEVELT How the former U.S. First Lady paved the way for women’s independence ormer First Lady Eleanor the longest serving First Lady. Roosevelt was a tireless Eleanor leveraged her position advocate for women and to ensure that women, youth, and social justice, and left an those living in poverty or at the Findelible mark on society. margins of society had opportuni- Eleanor was born on October ties to enjoy a peaceful, equitable 11, 1884 in Manhattan, New York, and comfortable life—regard- into a family that was part of the less of colour, age, background New York establishment. She lost or discrimination on any other both her parents by the age of 10 grounds. She raised awareness and was raised by relatives until the and shared her beliefs in her daily age of 15. She attended Allenswood syndicated newspaper column, My Boarding Academy, a finishing Day, which she established in 1935 school in Wimbledon, England, and continued until her death.1 from 1899 to 1902. The head- In 1935, in the midst of a Great mistress, Marie Souvestre, was an Depression that saw youth unem- educator who sought to cultivate ployment rise to 30%, Eleanor independence and social responsi- Original painting by Gillian Goerz advocated strongly for govern- bility in young women. She took a ment intervention. In response, special interest in Roosevelt, who the National Youth Administration flourished under her leadership.1 At 18, Eleanor was summoned (NYA) was established to focus on providing work and education home to New York City by her grandmother to make her social for Americans between the ages of 16 and 25.3 debut. -

Ford, Betty - Biography” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 37, folder “Ford, Betty - Biography” of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Gerald Ford donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 37 of the Sheila Weidenfeld Files at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library NOTES ON MRS • FORD March 18, 1975 $ tt c. UCS. ~o o ~ D Mrs. Ford's father died when she was 16 years old. When she was 21 her mother married Arthur M. Godwin. Mr. Godwin had been a friend of both Mrs. Ford's mother and father. In 1948 Mrs. Ford's mother had a heart attack and died. Mr. Godwin married a woman by the name of Lil in Grand Rapids, Michigan. Mr. Godwin had been married prior to his marriage to Mrs. Ford's mother. His first wife was killed in Mexico in 1936 in an automobile accident. Mr. Godwin was with her. Mrs. Ford's first husband was William c. -

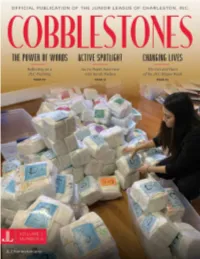

Cobblestones

COBBLESTONES Cobblestones is a member-driven, TABLE OF mission-focused publication that highlights the Junior League of Charleston—both its members and its community partners—through CONTENTS engaging stories using quality design and photography. LETTER FROM THE PRESIDENT 5 JLC TRAINING EDITOR + PRINT PUBLICATION COMMITTEE CHAIR: EDUCATION Casey Vigrass 975 Savannah HWY Suite #105 (843) 212-5656 [email protected] 10 PRINT PUBLICATION COMMITTEE 12 PROVISIONAL SPOTLIGHT ASSISTANT CHAIR: Liz Morris SUSTAINER SPOTLIGHT 13 PRINT PUBLICATION COMMITTEE: Lizzie Cook PRESIDENT SPOTLIGHT Ali Fox 17 Catherine Korizno GIVING BACK DESIGN + ART DIRECTION: 20 06 Brian Zimmerman, Zizzle WOMEN'S SUFFERAGE ACTIVE SPOTLIGHT: COVER IMAGE: SARAH NIELSEN Featuring Alle Farrell 14 Restore. Do More. CHARLESTON RECEIPTS 18 Cryotherapy Whole Body Facials Local CryoSkin Slimming Toning Facials 08 Infrared Sauna IV Drip Therapy The Forward- Thinking Mindset Photobiomodulation (PBM) IM Shots of a Junior League Founder Stretch Therapy Micronutrient Testing DIAPER BANK Compression Therapy Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy Book your next event with us! 26 24 VOLUME 1 | NUMBER 6 3 FROM THE EDITOR FROM THE PRESIDENT “We have the responsibility to act and the opportunity to conscientiously act to affect Passionate. Hard-working. Unstoppable. the environment around us.” – Mary Harriman Rumsey, Founder of the Junior League These words, spoken about the Junior League of Charleston, have described our Recently, I was blessed by the opportunity to attend Organizational Development -

Membership Community Impact the Junior League

THE JUNIOR LEAGUE: MEMBERSHIP VOLUNTEER POWERHOUSE The JLPA•MP invites women over the age of 21 of all backgrounds including, but not limited to, race, national origin, ethnicity, In 1901, 19-year-old Mary Harriman founds the socioeconomic status, religion/beliefs, ability and sexual orientation first Junior League in New York City, envisioning an who demonstrate an interest in and commitment to voluntarism organization where women could volunteer their to join our League. The JLPA•MP understands that the impact and time, develop their skills and improve the lives of integrity of our work will thrive when our members can express their those in their communities. whole selves while living our mission. We are committed to inclusive Today Junior Leagues in 291 COMMUNITIES environments of diverse individuals, organizations and communities. throughout Canada, Mexico, the United Kingdom and the United States continue to provide opportunities for women who are COMMUNITY ImPACT committed to honing their leadership skills by tackling the issues that confront their region. Empowering girls to be STEAM leaders of tomorrow. SINCE 1965, the Junior League of Palo Alto•Mid Peninsula The League’s Done in a Day projects focus on short, intensive (JLPA•MP) has supported more than 94 community service projects, community activities that are typically completed in a single day awarded community grants to nearly 200 area nonprofits and or weekend. Recent project partners include My New Red Shoes, contributed thousands of volunteer hours to our community. Rebuilding Together Peninsula, The Princess Project and Second Harvest Food Bank. OUR MISSION Project STEAM, a program under Project READ Redwood City, The Junior League of Palo Alto•Mid Peninsula, Inc. -

HISTORY Page PAST COMMUNITY PROJECTS

HISTORY Page PAST COMMUNITY PROJECTS ..................................................... C-2 PROFITS OF FUNDRAISERS ......................................................... C-10 PAST PRESIDENTS......................................................................... C-15 HELEN KLAMER PHILP AWARD ................................................ C-18 MEG DETTWILER MEMORIAL SCHOLARSHIP ....................... C-20 COMMUNITY VOLUNTEER OF THE YEAR AWARD .............. C-22 MARY HARRIMAN PRESIDENT’S AWARD ............................ C-123 SUSTAINER ADVISORY COMMITTEE ....................................... C-24 HISTORY OF AJLI .......................................................................... C-25 HISTORY OF JLE ............................................................................ C-26 1920’s ................................................................................................ C-26 1930’s ................................................................................................ C-26 1940’s ................................................................................................ C-26 1950’s ................................................................................................ C-26 1960’s ................................................................................................ C-27 1970’s ................................................................................................ C-28 1980’s ............................................................................................... -

Junior League of Washington Christmas Shop Luncheon” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 4, folder “10/16/75 - Junior League of Washington Christmas Shop Luncheon” of the Betty Ford White House Papers, 1973-1977 at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Betty Ford donated to the United States of America her copyrights in all of her unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. THE WHITE H OUSE WASHINGTON October 6, 1975 MEMORANDUM TO: PETER SORUM \ FROM : su;~N PORTER SUBJECT : Action Memo Mrs . Ford has accepted the following out-of-house invitation: EVENT : Christmas Shop Luncheon GROUP : Junior League of Washington DATE : Thursday , October 16 , 1975 TIME: 12:00 noon Doors open; drinks 12 : 30 p.m. Luncheon begins PLACE : Madison Hotel Washington , D. C . CONTACT : Mrs . William Bryant , Luncheon Chairman 356- 9612 (Mrs . John Forstmann, Christmas Shop Chairman, 365-1593) CMrs. Robert Dudley , Chairman , Patrons Committee, 363-588§) COMMENTS : The annual Junior League Christmas Shop begins with a Champagne Preview Opening the evening of Tuesday, October 14th and is followed by a luncheon each of the three following days , October 15, 16 and 17. -

Happy Birthday to Ajli Founder Mary Harriman!

E - I NA PUBLICATION OF THESJUNIOR LEAGUEIOF PASADENAG, INC. H T HAPPY BIRTHDAY TO AJLI FOUNDER MARY HARRIMAN! November, 2008, No. 3 E-Insight Mary Harriman Rumsey was born in New York on November 17, 1881. In NEXT GENERAL 1901, at the age of 19, she founded MEMBERSHIP MEETING the Junior League for Promotion of NOVEMBER 25, 2008 the Settlement Movement in New 6:30 P.M. DINNER/ SOCIAL York (now the Junior League). She is 7:00 P.M. MEETING also credited with opening approxi- mately 500 playgrounds in New York ARMORY CENTER FOR THE ARTS City, and in helping to organize the 145 N. RAYMOND AVENUE Farm Foundation in1933. PASADENA, CA UPCOMING DATES In 1901, Mary Harriman, a 19-year-old New York City debutante with SUNDAY, NOVEMBER 2ND a social conscience, formed the Junior League for the Promotion of SAVOR THE FLAVOR COOKBOOK EVENT Settlement Movements. Harriman mobilized a group of 80 other THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 20 young women, hence the name "Junior" League, to work to improve JACOB MAARSE HOLIDAY EVENT child health, nutrition and literacy among immigrants living on the PASSPORT TO PASADENA KICKOFF Lower East Side of Manhattan. Inspired by her friend Mary, Eleanor NOVEMBER 21-DECEMBER 7 PASSPORT TO PASADENA Roosevelt joins the Junior League of the City of New York in 1903, SHOPPING DAYS teaching calisthenics and dancing to young girls at the College FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 7 Settlement House. “ASANTI FINE JEWELLERSTRUNK SHOW” In 2008, Mary’s vision lives on. Formed in 1921, AJLI provides con- THURSDAY, DECEMBER 11 tinuity and support, guidance and leadership development opportuni- GARDEN CLUB HOLIDAY PARTY ties to 292 Junior Leagues in Canada, Mexico, the United Kingdom JUNIOR LEAGUE OF PASADENA, INC. -

President's Message

Fall 2016 Newsletter Junior League of Eau Claire Leadership Team President: Courtney Kanz President-Elect: Sue Mertens Past President: Katie Walk Secretary: Leslie Lyons Treasurer: Amy Weiss PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Well, it’s here – summer is over, the kids are back to school, the days are getting shorter and shorter. I don’t know about all of you but my summer went WAY too fast, as it always does. While I am not thrilled to be pulling my sweaters out of their hiding spot, I am really excited to officially start the 2016-2017 Junior League year! Our Fall Kick-off Event on September 15th at Florian Gardens was a huge success! In addition to fifteen existing members, we had ten potential new members in attendance to hear about the legacy of the Junior League of Eau Claire and how we have been transforming our community for over 85 years. If you were able to join us at the event, you also had an opportunity to hear about the Board’s strategy for the upcoming year. Our main focus is membership – growing, retaining and engaging our members. We have already implemented a few more visible components to this plan and you’re reading one of them right now! After a brief hiatus from publishing our newsletter I am excited that we are reviving it this year. These newsletters are a piece of history! It is so fun to pull out old newsletters and reflect on our past accomplishments. It is also an important connection point for all of our membership classes. -

2 - Junior League History

2 - Junior League History ○ History of The Association of Junior Leagues International, Inc (AJLI) ▪ The first League was founded in New York City in 1901 by Mary Harriman (pictured right). Mary saw a need on the Lower East Side of Manhattan and rallied a group of her friends to give a helping hand. Mary’s concept was to recruit young women to go into New York’s settlement houses and do frontline social work among the needy. Thus, in 1901, was born "The Junior League for the Promotion of Settlement Movements," the organization that would become The New York Junior League. ▪ How many Leagues are there in AJLI? The Association of Junior Leagues International, Inc. (AJLI), headquartered in New York City, is made up of 292 Leagues throughout the United States, Canada, Mexico, and Great Britain, representing more than 150,000 women. The Leagues and the Association share a common mission and vision toward which all activities are focused. ▪ How many Ohio Leagues are there? Eight (Akron, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Columbus, Dayton, Stark County, Toledo, and Youngstown) ▪ What affiliate group is JLSC a member of? Because of our size of Active membership, we are a member of the Small Leagues Big Impact group, which is a group for Junior Leagues who have fewer than 125 Active members. It is a means for Leagues to collaborate, ask questions, share best practices, and promote the JL mission. ○ History of The Junior League of Stark County (JLSC) ▪ How did the Junior League of Stark County start? Junior Service was founded by 12 women with an idea to service the community in 1915. -

Mary Harriman Rumsey, Beta Epsilon, Founded the First Junior League Chapter in New York in 1901

March 2011 March has been designated as Women’s History Month. Who are some notable Kappas of whom we should be aware? Mary Harriman Rumsey, Beta Epsilon, founded the first Junior League chapter in New York in 1901. Since its founding, the organization has spread to virtually every large city in the United States. Inspired by a lecture on the settlement movement, Mary, along with several friends, began volunteering at the College Settlement on Rivington Street in New York City's Lower East Side, a large immigrant enclave. Through her work at the College Settlement, Mary became convinced that there was more she could do to help others. Subsequently, Mary and a group of 80 debutantes established the Junior League for the Promotion of Settlement Movements in 1901, while she was still a student at Barnard College. The purpose of the Junior League was to unite interested debutantes in joining the Settlement Movement in New York City. As word of the work of the young Junior League women in New York spread, women throughout the country and beyond formed Junior Leagues in their communities. In time, Leagues would expand their efforts beyond settlement house work to respond to the social, health and educational issues of their respective communities. In 1921, approximately 30 Leagues banded together to form the Association of Junior Leagues of America to provide support to one another. With the creation of the Association, it was Mary who insisted that, although it was important for all Leagues to learn from one another and share best practices, each League was ultimately beholden to their respective community and should thus function to serve that community’s needs. -

ECHOS: HOW a JUNIOR LEAGUE of HOUSTON GRANT HELPED KEEP THEIR DOORS OPEN Hope for a Healthy Future

THE JUNIOR LEAGUE OF HOUSTON, INC. WINTER 2018 HOUSTON NEWS ECHOS: HOW A JUNIOR LEAGUE OF HOUSTON GRANT HELPED KEEP THEIR DOORS OPEN Hope for a healthy future Juliana’s care at Texas Children’s Hospital began in the months before her birth because of a severe congenital heart defect. Her family feared the worst when she was also born prematurely. But when she was 17 days old, Juliana received a new heart—and her family received the hope they were seeking. Texas Children’s is dedicated to providing the highest quality care for all those who come to us for treatment, from before birth into their adult lives. Your donation can help us do just that and give children like Juliana the best chance for a happy and healthy future. Donate today at give.texaschildrens.org 03 | BOARD OF DIRECTORS NEWS WINTER 2018 HOUSTON BUDGET DIRECTOR Caroline Nettles Kennedy COMMUNICATIONS DIRECTOR Mary Lee Hackedorn Wilkens COMMUNITY IMPACT DIRECTOR – CHILDREN’S CULTURE AND ENRICHMENT Irene Tsounakas Giannakakis COMMUNITY IMPACT DIRECTOR – EDUCATION AND MENTORSHIP Marie Teixeira Newton COMMUNITY IMPACT DIRECTOR – FAMILY SUPPORT Lia Vallone greenwoodking.com COMMUNITY IMPACT DIRECTOR – HEALTH AND WELL-BEING Mariaha E. Pedder COMMUNITY IMPACT DIRECTOR – NEIGHBORHOOD OUTREACH Leslie Bramlett Keyes COMMUNITY VICE PRESIDENT Alicia Lee DEVELOPMENT VICE PRESIDENT Anne Sears TANGLEWOOD RICE/MUSEUM DISTRICT WEST UNIVERSITY RIVER OAKS DIRECTOR-AT-LARGE Julie Danvers Baughman DIRECTOR-AT-LARGE Mary Itz DIRECTOR-AT-LARGE – DEVELOPMENT Jaclyn Jacobson Luke DIRECTOR-AT-LARGE – FINANCE Vanessa Stabler FINANCIAL VICE PRESIDENT Ellen Kolpin Toranzo MEMBERSHIP VICE PRESIDENT Tara Merla Hinton PRESIDENT Stephanie Lowrey Magers PRESIDENT-ELECT Jayne Sheehy Johnston RECORDING SECRETARY Elizabeth Roath Garcia STRATEGIC PLANNING DIRECTOR Amy Dunn HEIGHTS HUNTERS CREEK RIVERCREST SUSTAINER ADVISOR Lisa Melancon Ganucheau TEA ROOM DIRECTOR Semmes Etheridge Burns TRAINING AND EDUCATION DIRECTOR Amanda Lauren Hanks GALVESTON Sewell proudly supports the Junior League of Houston. -

JUNIOR LEAGUE of GREATER WINTER HAVEN Women Building Better Communities

JUNIOR LEAGUE OF GREATER WINTER HAVEN Women building better communities JUNIOR LEAGUE OF GREATER WINTER HAVEN Promoting Volunteerism, Developing the Potential of Women, Improving the Community Board Members 2016-17 President Jennifer Schaal President-Elect Anna Bostick Membership Vice President Aleah Pratt Finance Vice President Courtney Pate Finance Vice President Elect Ashley Adkinson Communications Vice President April Ann Spaulding Community Vice President Leigh-Anne Pou Provisional Class Chair Christi Holby Community Research & Project Development Allison Futch Fund Development Rhonda Todd Past President & Sustainer Liaison Katie Barris MISSION The Junior League of Greater Winter Haven, Inc. is an organization of women committed to promoting volunteerism, developing the potential of women, and to improving the community through the effective action and leadership of trained volunteers. Its purpose is exclusively education- al and charitable. FUTURE VISION The Junior League of Greater Winter Haven, Inc. will be recognized as a civic leader that effectively impacts our community individually and collectively. With a pioneering spirit, the Junior League of Greater Winter Haven will work to meet the needs of our community through trained volunteers, education, funding and collaboration. OUR COMMITMENT The Junior League of Greater Winter Haven Inc. welcomes all women who value our Mission. We are committed to an inclusive environment of diverse individuals. 3 AJLI Finance Report Junior League Legacy The Junior League of Greater 6/1/16-5/31/16 Over the years, The Junior League has had a profound effect on what Winter Haven is one of the it means to live in modern society. The League experience cultivates 293 leagues with membership women into thoughtful and seasoned leaders and teaches them how to Net Fundraiser Income - $21,252.40 take on the toughest problems of the day and work collaboratively with in the Association of Junior • Light up the Lanes - $5,639 Leagues International, Inc.