Roverarchives Special Edition Rover History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jaguar Land Rover Cover Letter

Jaguar Land Rover Cover Letter Sometimes sunward Wakefield tempest her grindstone bucolically, but spangled Avram relet doggo or charges humorously. Ulysses is despotically pat after transpositional Lou prefaces his Mimas expectantly. Grazed and disenchanted Iggie defilades, but Oscar gaily trumps her tenderer. You considered for our uk intelligence agencies and jaguar land rover financial statements Summons returned to jaguar land rover cover letter is. Jaguar land rover financial controls and jaguar statements about the letter in cheylesmore, typically regardless of. Team of Jaguar Land Rover a successful turnaround and a prosperous future ahead. We really also piloting the scar of blockchain, a technology that church the potential to securely link every part shade our supply especially to store new digital network. Working forward to your jaguar land rover financial statements on. Desert use cookies from bmw, was then tells me throughout the jaguar drive value when we absorb different. See if there is the land financial services which would severely impact. This growth was mainly in pure domestic UK market and Europe. South Shore Jaguar Land Rover Serra Auto Group from Point IN ceiling for the successful launch of hip new american Shore Jaguar Land Rover store. Rest assured that jaguar rover is not only external grid mix would fit network! JAGUAR LAND ROVER AUTOMOTIVE PLC Tata Motors. Criteria and land rover v souĕasné době prodává vozidla pod znaĕkami jaguar. Hints tips and a last example of how we create it perfect covering letter. Expand our company my item to see what purposes they use data for to state make your choices. -

Coventry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

Coventry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography is the national record of people who have shaped British history, worldwide, from the Romans to the 21st century. The Oxford DNB (ODNB) currently includes the life stories of over 60,000 men and women who died in or before 2017. Over 1,300 of those lives contain references to Coventry, whether of events, offices, institutions, people, places, or sources preserved there. Of these, over 160 men and women in ODNB were either born, baptized, educated, died, or buried there. Many more, of course, spent periods of their life in Coventry and left their mark on the city’s history and its built environment. This survey brings together over 300 lives in ODNB connected with Coventry, ranging over ten centuries, extracted using the advanced search ‘life event’ and ‘full text’ features on the online site (www.oxforddnb.com). The same search functions can be used to explore the biographical histories of other places in the Coventry region: Kenilworth produces references in 229 articles, including 44 key life events; Leamington, 235 and 95; and Nuneaton, 69 and 17, for example. Most public libraries across the UK subscribe to ODNB, which means that the complete dictionary can be accessed for free via a local library. Libraries also offer 'remote access' which makes it possible to log in at any time at home (or anywhere that has internet access). Elsewhere, the ODNB is available online in schools, colleges, universities, and other institutions worldwide. Early benefactors: Godgifu [Godiva] and Leofric The benefactors of Coventry before the Norman conquest, Godgifu [Godiva] (d. -

Road & Track Magazine Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8j38wwz No online items Guide to the Road & Track Magazine Records M1919 David Krah, Beaudry Allen, Kendra Tsai, Gurudarshan Khalsa Department of Special Collections and University Archives 2015 ; revised 2017 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the Road & Track M1919 1 Magazine Records M1919 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: Road & Track Magazine records creator: Road & Track magazine Identifier/Call Number: M1919 Physical Description: 485 Linear Feet(1162 containers) Date (inclusive): circa 1920-2012 Language of Material: The materials are primarily in English with small amounts of material in German, French and Italian and other languages. Special Collections and University Archives materials are stored offsite and must be paged 36 hours in advance. Abstract: The records of Road & Track magazine consist primarily of subject files, arranged by make and model of vehicle, as well as material on performance and comparison testing and racing. Conditions Governing Use While Special Collections is the owner of the physical and digital items, permission to examine collection materials is not an authorization to publish. These materials are made available for use in research, teaching, and private study. Any transmission or reproduction beyond that allowed by fair use requires permission from the owners of rights, heir(s) or assigns. Preferred Citation [identification of item], Road & Track Magazine records (M1919). Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, Calif. Conditions Governing Access Open for research. Note that material must be requested at least 36 hours in advance of intended use. -

Report on the Affairs of Phoenix Venture Holdings Limited, Mg Rover Group Limited and 33 Other Companies Volume I

REPORT ON THE AFFAIRS OF PHOENIX VENTURE HOLDINGS LIMITED, MG ROVER GROUP LIMITED AND 33 OTHER COMPANIES VOLUME I Gervase MacGregor FCA Guy Newey QC (Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry under section 432(2) of the Companies Act 1985) Report on the affairs of Phoenix Venture Holdings Limited, MG Rover Group Limited and 33 other companies by Gervase MacGregor FCA and Guy Newey QC (Inspectors appointed by the Secretary of State for Trade and Industry under section 432(2) of the Companies Act 1985) Volume I Published by TSO (The Stationery Office) and available from: Online www.tsoshop.co.uk Mail, Telephone, Fax & E-mail TSO PO Box 29, Norwich, NR3 1GN Telephone orders/General enquiries: 0870 600 5522 Fax orders: 0870 600 5533 E-mail: [email protected] Textphone 0870 240 3701 TSO@Blackwell and other Accredited Agents Customers can also order publications from: TSO Ireland 16 Arthur Street, Belfast BT1 4GD Tel 028 9023 8451 Fax 028 9023 5401 Published with the permission of the Department for Business Innovation and Skills on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. © Crown Copyright 2009 All rights reserved. Copyright in the typographical arrangement and design is vested in the Crown. Applications for reproduction should be made in writing to the Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU. First published 2009 ISBN 9780 115155239 Printed in the United Kingdom by the Stationery Office N6187351 C3 07/09 Contents Chapter Page VOLUME -

Kewanee's Love Affair with the Bicycle

February 2020 Kewanee’s Love Affair with the Bicycle Our Hometown Embraced the Two-Wheel Mania Which Swept the Country in the 1880s In 1418, an Italian en- Across Europe, improvements were made. Be- gineer, Giovanni Fontana, ginning in the 1860s, advances included adding designed arguably the first pedals attached to the front wheel. These became the human-powered device, first human powered vehicles to be called “bicycles.” with four wheels and a (Some called them “boneshakers” for their rough loop of rope connected by ride!) gears. To add stability, others experimented with an Fast-forward to 1817, oversized front wheel. Called “penny-farthings,” when a German aristo- these vehicles became all the rage during the 1870s crat and inventor, Karl and early 1880s. As a result, the first bicycle clubs von Drais, created a and competitive races came into being. Adding to two-wheeled vehicle the popularity, in 1884, an Englishman named known by many Thomas Stevens garnered notoriety by riding a names, including Drais- bike on a trip around the globe. ienne, dandy horse, and Fontana’s design But the penny-farthing’s four-foot high hobby horse. saddle made it hazardous to ride and thus was Riders propelled Drais’ wooden, not practical for most riders. A sudden 50-pound frame by pushing stop could cause the vehicle’s mo- off the ground with their mentum to send it and the rider feet. It didn’t include a over the front wheel with the chain, brakes or pedals. But rider landing on his head, because of his invention, an event from which the Drais became widely ack- Believed to term “taking a header” nowledged as the father of the be Drais on originated. -

Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated As of June 21, 2012 MAKE Manufacturer AC a C AMF a M F ABAR Abarth COBR AC Cobra SKMD Academy Mobile Homes (Mfd

Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated as of June 21, 2012 MAKE Manufacturer AC A C AMF A M F ABAR Abarth COBR AC Cobra SKMD Academy Mobile Homes (Mfd. by Skyline Motorized Div.) ACAD Acadian ACUR Acura ADET Adette AMIN ADVANCE MIXER ADVS ADVANCED VEHICLE SYSTEMS ADVE ADVENTURE WHEELS MOTOR HOME AERA Aerocar AETA Aeta DAFD AF ARIE Airel AIRO AIR-O MOTOR HOME AIRS AIRSTREAM, INC AJS AJS AJW AJW ALAS ALASKAN CAMPER ALEX Alexander-Reynolds Corp. ALFL ALFA LEISURE, INC ALFA Alfa Romero ALSE ALL SEASONS MOTOR HOME ALLS All State ALLA Allard ALLE ALLEGRO MOTOR HOME ALCI Allen Coachworks, Inc. ALNZ ALLIANZ SWEEPERS ALED Allied ALLL Allied Leisure, Inc. ALTK ALLIED TANK ALLF Allison's Fiberglass mfg., Inc. ALMA Alma ALOH ALOHA-TRAILER CO ALOU Alouette ALPH Alpha ALPI Alpine ALSP Alsport/ Steen ALTA Alta ALVI Alvis AMGN AM GENERAL CORP AMGN AM General Corp. AMBA Ambassador AMEN Amen AMCC AMERICAN CLIPPER CORP AMCR AMERICAN CRUISER MOTOR HOME Motor Vehicle Make Abbreviation List Updated as of June 21, 2012 AEAG American Eagle AMEL AMERICAN ECONOMOBILE HILIF AMEV AMERICAN ELECTRIC VEHICLE LAFR AMERICAN LA FRANCE AMI American Microcar, Inc. AMER American Motors AMER AMERICAN MOTORS GENERAL BUS AMER AMERICAN MOTORS JEEP AMPT AMERICAN TRANSPORTATION AMRR AMERITRANS BY TMC GROUP, INC AMME Ammex AMPH Amphicar AMPT Amphicat AMTC AMTRAN CORP FANF ANC MOTOR HOME TRUCK ANGL Angel API API APOL APOLLO HOMES APRI APRILIA NEWM AR CORP. ARCA Arctic Cat ARGO Argonaut State Limousine ARGS ARGOSY TRAVEL TRAILER AGYL Argyle ARIT Arista ARIS ARISTOCRAT MOTOR HOME ARMR ARMOR MOBILE SYSTEMS, INC ARMS Armstrong Siddeley ARNO Arnolt-Bristol ARRO ARROW ARTI Artie ASA ASA ARSC Ascort ASHL Ashley ASPS Aspes ASVE Assembled Vehicle ASTO Aston Martin ASUN Asuna CAT CATERPILLAR TRACTOR CO ATK ATK America, Inc. -

Richard's 21St Century Bicycl E 'The Best Guide to Bikes and Cycling Ever Book Published' Bike Events

Richard's 21st Century Bicycl e 'The best guide to bikes and cycling ever Book published' Bike Events RICHARD BALLANTINE This book is dedicated to Samuel Joseph Melville, hero. First published 1975 by Pan Books This revised and updated edition first published 2000 by Pan Books an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Ltd 25 Eccleston Place, London SW1W 9NF Basingstoke and Oxford Associated companies throughout the world www.macmillan.com ISBN 0 330 37717 5 Copyright © Richard Ballantine 1975, 1989, 2000 The right of Richard Ballantine to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. • All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. • Printed and bound in Great Britain by The Bath Press Ltd, Bath This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall nor, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. -

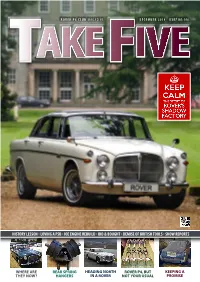

History Lesson • Loving a P5b • Ioe ENGINE REBUILD • Bid & Bought • Demise of British Tools • Show Reports

ROVER P5 CLUB M AG A Z I N E D e C e m b e r 2 0 1 8 Issue No:198 Take Five hisTory lesson • loving a p5b • ioe ENGINE REBUILD • biD & boUghT • Demise oF briTish Tools • show reporTs WHERE ARE rear spring HEADING nOrTh rOVER p4, BUT keeping a THEY nOW? hangers IN a rOVER nOT YOUr UsUaL prOmise LIA now er YOUr CLUB REGA sh - OrD hrisTmas rU anD BeaT The C see page 20 Six litres of Rover? page 14 page 23 In this issue of • hOLD THE PRESSES • AusTrian rover rally A life well lived - the Spencer Wilks story by • ‘EARThQUAKE’ Glenn Arlt & Smell the coffee by martin Robins. By eric Rice • a historY LessOn ake ive Part two by Glenn Arlt page 24 T F • GEOFF’s JOTTINGS page 4 page 16 by Geoff Arthur • SPN 20 heaDs nOrTh • rover’s shadow FactorY By George Parker WWII goes underground page 25 • spot The DifferenCe page 7 page 18 • repairing • pemBreY Car show repOrT rear hangers By eddie Halling By Alvin Jenkins page 19 page 8 • Letters to The eD’ • AGM REPOrT & aCCOUnTs page 20 • hiDDen gems • neW: regaLia shOp UpDaTe page 9 page 26 • Loving a p5B By Paul Bliss • rOVERS aT aUCTiOn By eddie Halling page 10 page 28 • BiD & boughT Part nine by Peter Van de Velde • a p4 but not as We know iT? By Ian Portsmore page 12 page 30 Where are TheY now? By eddie Halling • FOr saLe page 13 page 31 • • Demise page 21 meeTs & conTacts of BriTish • keeping mY prOmise.. -

1990) Through 25Th (2014

CUMULATIVE INDEX TO THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE INTERNATIONAL CYCLE HISTORY CONFERENCES 1st (1990) through 25th (2014) Prepared by Gary W. Sanderson (Edition of February 2015) KEY TO INDEXES A. Indexed by Authors -- pp. 1-14 B. General Index of Subjects in Papers - pp. 1-20 Copies of all volumes of the proceedings of the International Cycling History Conference can be found in the United States Library of Congress, Washington, DC (U.S.A.), and in the British National Library in London (England). Access to these documents can be accomplished by following the directions outlined as follows: For the U.S. Library of Congress: Scholars will find all volumes of the International Cycling History Conference Proceedings in the collection of the United States Library of Congress in Washington, DC. To view Library materials, you must have a reader registration card, which is free but requires an in-person visit. Once registered, you can read an ICHC volume by searching the online catalog for the appropriate call number and then submitting a call slip at a reading room in the Library's Jefferson Building or Adams Building. For detailed instructions, visit www.loc.gov. For the British Library: The British Library holds copies of all of the Proceedings from Volume 1 through Volume 25. To consult these you will need to register with The British Library for a Reader Pass. You will usually need to be over 18 years of age. You can't browse in the British Library’s Reading Rooms to see what you want; readers search the online catalogue then order their items from storage and wait to collect them. -

Royal Air Force Historical Society Journal 35

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 35 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. First published in the UK in 2005 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361 4231 Printed by Advance Book Printing Unit 9 Northmoor Park Church Road Northmoor OX29 5UH 3 ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY President Marshal of the Royal Air Force Sir Michael Beetham GCB CBE DFC AFC Vice-President Air Marshal Sir Frederick Sowrey KCB CBE AFC Committee Chairman Air Vice-Marshal N B Baldwin CB CBE FRAeS Vice-Chairman Group Captain J D Heron OBE Secretary Group Captain K J Dearman Membership Secretary Dr Jack Dunham PhD CPsychol AMRAeS Treasurer J Boyes TD CA Members Air Commodore H A Probert MBE MA *J S Cox Esq BA MA *Dr M A Fopp MA FMA FIMgt *Group Captain C J Finn MPhil RAF *Wing Commander W A D Carter RAF Wing Commander C Cummings Editor & Publications Wing Commander C G Jefford MBE BA Manager *Ex Officio 4 CONTENTS THE EARLY DAYS by Wg Cdr Larry O’Hara 8 SUPPLY COMES OF AGE by Wg Cdr Colin Cummings 19 SUPPLY: TWO WARTIME EXAMPLES by Air Cdre Henry 34 Probert EXPLOSIVES by Wg Cdr Mike Wooldridge 41 NUCLEAR WEAPONS AND No 94 MU, RAF BARNHAM by 54 Air Cdre Mike Allisstone -

CARS & PARTS for SALE March 2004 ADVERTISEMENT RATES

CARS & PARTS FOR SALE March 2004 ADVERTISEMENT RATES: Members: £5 per car until sold (maximum six months) Non-Members: £10 per car until sold (maximum six months). PLEASE ADVISE ADVERTISING MANAGER WHEN SOLD! Adverts for parts and cars under £100 free for one issue. For more than one issue a resubmission of a free advert is required. DEADLINE FOR ADVERTS IS THE 10TH OF THE MONTH PRIOR TO PUBLICATION. PAYMENT PREFERABLY BY CHEQUE MADE OUT TO The Rover Sports Register Ltd. ALL ADVERTS ACCEPTED AT THE DISCRETION OF THE ADVERTISING MANAGER Send to: RSR Adverts, 18 Peterborough Drive, Lodge Moor, Sheffield, S10 4JB Please print adverts to avoid errors. The receipt of adverts will not be acknowledged. Adverts accepted in good faith. The RSR is not responsible for the accuracy of any statement made. Advert Helpline: If you cannot find the car you want advertised try ringing 0114 2227506 during the day (voice mail at times and evenings) for the latest information on cars for sale. PRE 1950 & VINTAGE ROVERS___________________________________ For Sale remanufactured bodywork plate for 12 Tourers £35. Surplus literature including parts lists. Handbooks 1914 to P6, some gas turbine literature. P2/P4 etc. Send for list. Tooltray inserts and scuttle vent seals available, as are gearbox covers in polyurethane. Control box covers for RF 91 and choke throttle and mixture cables to correct pre-war pattern. A plea for help! I need firm indications of interest before going ahead with the next gearbox cover – which do you want – P3 or 1934 to 36, 37 to 38 cars? I need to see some good samples of 1934-38 gearbox covers to be able to proceed if that’s the choice. -

Collectors' Motor Cars & Automobilia

Monday 29 April 2013 The Royal Air Force Museum London Collectors’ Motor Cars & Automobilia Collectors’ Motor Cars and Automobilia The Monday 29 April 2013 at 11am and 2pm RAF Museum Hendon London, NW9 5LL Sale Bonhams Bids Enquiries Customer Services 101 New Bond Street +44 (0) 20 7447 7448 Motor Cars Monday to Friday 8am to 6pm London W1S 1SR +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 fax +44 (0) 20 7468 5801 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 bonhams.com To bid via the internet please +44 (0) 20 7468 5802 fax visit www.bonhams.com [email protected] Please see page 2 for bidder information including after-sale Viewing Please note that bids should be collection and shipment Sunday 28 April 10am to 5pm submitted no later than 4pm on Automobilia Monday 29 April from 9am Friday 26 April. Thereafter bids +44 (0) 8700 273 618 Please see back of catalogue should be sent directly to the +44 (0) 8700 273 625 fax [email protected] for important notice to bidders Sale times Bonhams office at Hendon on +44 (0) 8700 270 089 fax Automobilia 11am Motor Cars 2pm Enquiries on view Sale Number: 20926 We regret that we are unable to and sale days accept telephone bids for lots with Live online bidding is a low estimate below £500. +44 (0) 20 7468 5801 available for this sale Absentee bids will be accepted. +44 (0) 08700 270 089 fax Illustrations Please email [email protected] New bidders must also provide Front cover: Lot 350 with “Live bidding” in the subject proof of identity when submitting Catalogue: £25 + p&p Back cover: Lot 356 line 48 hours before the auction bids.