THE EDUCATION of ALEXANDER HAMILTON the Education of Alexander Hamilton

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

T a b l e C o n T e n T s I s s u e 9 s u mm e r 2 0 1 3 o f pg 4 pg 18 pg 26 pg 43 Featured articles Pg 4 abraham lincoln and Freedom of the Press A Reappraisal by Harold Holzer Pg 18 interbranch tangling Separating Our Constitutional Powers by Judith s. Kaye Pg 26 rutgers v. Waddington Alexander Hamilton and the Birth Pangs of Judicial Review by David a. Weinstein Pg 43 People v. sanger and the Birth of Family Planning clinics in america by Maria T. Vullo dePartments Pg 2 From the executive director Pg 58 the david a. Garfinkel essay contest Pg 59 a look Back...and Forward Pg 66 society Officers and trustees Pg 66 society membership Pg 70 Become a member Back inside cover Hon. theodore t. Jones, Jr. In Memoriam Judicial Notice l 1 From the executive director udicial Notice is moving forward! We have a newly expanded board of editors Dearwho volunteer Members their time to solicit and review submissions, work with authors, and develop topics of legal history to explore. The board of editors is composed J of Henry M. Greenberg, Editor-in-Chief, John D. Gordan, III, albert M. rosenblatt, and David a. Weinstein. We are also fortunate to have David l. Goodwin, Assistant Editor, who edits the articles and footnotes with great care and knowledge. our own Michael W. benowitz, my able assistant, coordinates the layout and, most importantly, searches far and wide to find interesting and often little-known images that greatly compliment and enhance the articles. -

The Church Militant: the American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92

The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Peter Walker All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Church Militant: The American Loyalist Clergy and the Making of the British Counterrevolution, 1701-92 Peter W. Walker This dissertation is a study of the loyalist Church of England clergy in the American Revolution. By reconstructing the experience and identity of this largely-misunderstood group, it sheds light on the relationship between church and empire, the role of religious pluralism and toleration in the American Revolution, the dynamics of loyalist politics, and the religious impact of the American Revolution on Britain. It is based primarily on the loyalist clergy’s own correspondence and writings, the records of the American Loyalist Claims Commission, and the archives of the SPG (the Church of England’s missionary arm). The study focuses on the New England and Mid-Atlantic colonies, where Anglicans formed a religious minority and where their clergy were overwhelmingly loyalist. It begins with the founding of the SPG in 1701 and its first forays into America. It then examines the state of religious pluralism and toleration in New England, the polarising contest over the proposed creation of an American bishop after the Seven Years’ War, and the role of the loyalist clergy in the Revolutionary War itself, focusing particularly on conflicts occasioned by the Anglican liturgy and Book of Common Prayer. -

The Signal, Vol. 70, No. 7 (December 16, 1955)

C*> LIBBARY^ . NEW JIPSEY^ f ^ ( STATE TEACHER COLLET ag!€®tg(gtgigtf!g!s!€tg«ste®'e!s®ts - TRENTONTREJNlw^ |S tate Wins Over |E ast Stroudsburg STATE! SIGNAL ! 98-97 Sl®3>;&<St2s&3®iaSi&2r«3'<2i&: VOL. LXX, No. 7 STATE TEACHERS COLLEGE AT TRENTON, NEW JERSEY FRIDAY, DECEMBER 16, 1955 Colleges Send Congratulatory Messages Yuletide Spirit Dominates Social Life— Commemorating States Centennial Year D ecorations Brighten Campus Festivities Letters are pouring in from all Mindham, New Jersey, in their con parts of the world to Santa Claus, gratulatory letter, said, "God's richest but St. Nick isn't the only one who blessings attend your efforts and those Snowfall Sets Scene for Christmas Activities; Students Enjoy is snowed under by letters. Doctor of your confreres. May he lend you Formal, Concert, Carolers, Parti| Roscoe West has a special folder in powerful assistance to be an instru his files which holds many letters ment of spiritual enrichment and which was ber 11, featured a group called the from many places in New Jersey con benediction to others." As we travel in various directions ditional Christm; Ips Hall. At Madrigal Singers. Jane Aeschback and gratulating him and the college on Christmas is a -Unie of prayer, a homeward today, the yuletide spirit held this yptlr in Phi vill travel with us. Chc|tmasAame the dance/the Carolerj came "A-Was- Audrey Kisby, sopranos; Fran Bruno our birthday. feeling of closeneslf^tip J3fid. Let us time an con- and Natalie Levy, altos; Robert Per- The most impressive document re thank Hli for our successful pa^ fy this year at State.flWor the past sailingl^for the firs 'ery kchief and William Hullfish, tenors; ceived, s ent by Princeton University, and askf||dr a future as ptfpjductiv »e have decked the campus to serenade bliHg decorations^jflid, f esltiv il th Harry Grod and John Shagg, was written in Latin. -

Download Searchable

/& A^ S^^lS^, /.cr^S^^^^/iil &i^ ^ * * -^ iy^^nrfc*< //^*^^ c^^^^-^^*-^... ^ A^ __^ 1 ^i-^J THE BLACK BOOK PAGE 15 OF ORIGINAL MANUSCRIPT IN HANDWRITING OF MYLES COOPER The BLACK BOOK, or BOOK OF MIS DEMEANORS in KING'S COLLEGE, New-York, ijji-i-jjz,. Now published for the first Time. New-York: Printed for COLUMBIANA atthe UNIVERSITYPRESS, M.CM.XXXI. Edited and annotated by MILTON HALSEY THOMAS, B.Sc. Curator of Columbiana Reprinted from the COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY QUARTERLY March, 1931, Vol. XXIII, No. i FOREWORD Columbia is most fortunate in having had preserved through a hundred and sixty years that extraordinary docu ment, "The Book of Misdemeanours in King's College, New York." Myles Cooper, coming to the College after seven years at Oxford, did much to fit it into the pattern of his alma mater, and as part of his system of rigid discipline he introduced the Black Book, which had been for centuries a tradition at Queen's College, Oxford. In its pages, as in no other record which has come down to us, we can be with the students of King's College day by day in the most inti mate manner. Aside from its interest as a human docu ment, the Black Book has great value as an unconsciously transmitted source-book with its off-hand mention of facts which historians will eagerly pounce upon. The original is a black leather volume measuring seven and three-fourths by six and one-fourth inches; it is a blank- book of about a hundred and fifty leaves, of which only the first thirty-one pages and the last page bear writing. -

Clarke Moore

REVEREND PROFESSOR CLEMENT CLARKE MOORE “NARRATIVE HISTORY” IS FABULATION, HISTORY IS CHRONOLOGY “Stack of the Artist of Kouroo” Project Clement Clarke Moore HDT WHAT? INDEX CLEMENT CLARKE MOORE CLEMENT CLARKE MOORE 1779 July 15, Thursday: Clement Clarke Moore was born in Manhattan, the only child of heiress Charity Clarke and Dr. Benjamin Moore, Episcopal Bishop of New York, Rector of Trinity Church, and President of Columbia College. HDT WHAT? INDEX CLEMENT CLARKE MOORE CLEMENT CLARKE MOORE 1798 Clement Clarke Moore graduated 1st in his class from Columbia University. As a graduation speaker might have remarked, a great future lay ahead. “Hail, Columbia” was popular as a song — and not just among the members of the graduating class of Columbia University. HDT WHAT? INDEX CLEMENT CLARKE MOORE CLEMENT CLARKE MOORE 1804 The Reverend Clement Clarke Moore attacked Thomas Jefferson anonymously in OBSERVATIONS UPON CERTAIN PASSAGES IN MR. JEFFERSON’S NOTES ON VIRGINIA, WHICH APPEAR TO HAVE A TENDENCY TO SUBVERT RELIGION AND ESTABLISH A FALSE PHILOSOPHY. He reported that he had been made suspicious, when this deep thinker started writing about mountains. It was clear that he was going to make an attempt to use the facts of geology to argue that the BIBLE contained incorrect information as to the age of the earth: “Whenever modern philosophers talk about mountains, something impious is likely to be near at hand.” READ JEFFERSON TEXT It was presumably necessary for the Reverend to issue this tract anonymously, since although he was accusing the President of racism for his remark that “among the blacks there is misery enough, God knows, but not poetry,” his own family, a family that was immensely wealthy, owned the black slaves Thomas, Charles, Ann, and Hester and was in no hurry to set them free. -

John Vardill: a Loyalist's Progress

JOHN VARDILL: A LOYALIST'S PROGRESS by STEVEN GRAHAM WIGELY .A., University of California at Irvine, 1971 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA May, 1975 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of History The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada V6T 1W5 ABSTRACT This thesis is a study of a loyalist of the American Revolution named John .Vardill. A native of New York who went to England in 1774, he was an Anglican clergyman, a pamphlet• eer, a professor at King's College (New York), and a spy for the British. The purpose of the thesis is: 1. to tell his story, and 2. to argue that his loyalism was a perfectly rea• sonable consequence of his environment and experiences. The text begins with an Introduction (Chapter I) which places Vardill in colonial and English society, and justifies studying one who was neither among the very powerful nor the very weak. It then proceeds to a consideration of the circum• stances and substance of his claim for compensation from the , British government after the war (Chapter II). -

Over Odious Fumes in 1889 the Benjamin Moore Ing Impulses He Gave the Entire Days Did a Brief Stint Here

4 New»pap«* Dttotad Fririy, Dearly ^e Community Interest ., And Impartially Each Week F-ll Local Gorerage Complete News Pictures xxXIX-NO. 24 FRIDAY, SEPTEMBER I960 Benjamin Moore & Co. Plant Flourished M Owl-« //a// o/ a Century; Helped Growth of kro For AduU IIMItori Note; Thin In an- slon other in * trrln of article* slowed him but did not.Moore Paint, Company of St. Join Sweeney Corporal r Pro- on Carters Induntrlct and prevent him and his brother!Louis in 1917. In 1925 a new,duction Manager. wmiam. with a capital ofimodern plant was ereoted lni In addition to I, P the rolt they pltyN| |n thf borough pr«(rfn.i W.000, from forming Moore^ewark. who regularly visited the Car-Education CourtAction Monday Brotners. manufacturers of cal- Due to his basic planning.,terct whiting and varnish oper- 0 h WRlls ftnd w11 bpnt for CARTERET A U neneru I? "* . ' " organisation, develop-!ation during Harold I. Haskins Will tlons a^o. when •-;ngs ln 1883. His brother Wil-ment and research and that of,tenure as resident manager ln ,11am withdrew, was replaced by hIs nephew, L. P. Moore, known1 the 1920's to 1940s, President Next Monday; (lourw Moore ft Company was borr. the country'j best sellers were another brother, Robert, and for the stimulating sales ereat- B. M. Belcher in his earlier On Stocks Included Over Odious Fumes in 1889 the Benjamin Moore ing Impulses he gave the entire days did a brief stint here. His the engaging stories of Horatio Corporation was formed with a'organization, we find Benjamin father, W. -

Development of a Curriculum in the Early American Colleges Author(S): Joe W

The Development of a Curriculum in the Early American Colleges Author(s): Joe W. Kraus Source: History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 1, No. 2, (Jun., 1961), pp. 64-76 Published by: History of Education Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/367641 Accessed: 02/05/2008 14:31 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=hes. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We enable the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org THE DEVELOPMENT OF A CURRICULUM IN THE EARLY AMERICAN COLLEGES Joe W. Kraus The early American colleges were smaller and poorer counter- parts of the universities of Great Britain, rather than indigenous institutions, and the mother country was the source of their cur- riculum. -

Pension Application for Robert Troup W.16450 (Widow: Jennet) Married February 18, 1787, Her Maiden Name Was Jennet Goelet

Pension Application for Robert Troup W.16450 (Widow: Jennet) Married February 18, 1787, her maiden name was Jennet Goelet. He died January 14, 1832. Declaration. In order to obtain the benefit of the Act of Congress of the 7th July 1838 entitled “An Act granting half pay and pensions to certain widows.” State of New York County of New York SS On this seventh day of October one thousand eight hundred and thirty nine personally appeared before me—Judah Hammond—one of the Judges of the Marine Court in and for the City and County of New York Jennet Troup a resident of the City of New York in said County of New York aged seventy eight years who being first duly sworn according to law, doth on his oath make the following declaration in order to obtain the benefit of the provision made by the Act of Congress passed July 7th 1838 entitled “An act granting half pay and pensions to certain widows”— That she is the Widow of Robert Troup who was an officer in the war of the Revolution. That she has been informed and believes that said Robert Troup first entered the service of the United States in the early part of said war as a Lieutenant in a Corps of [?] That he was taken prisoner at the Battle of Long Island and confined many months in one of the prison ships. That when exchanged he was transferred to the Military family of General Gates and served as his aid with the rank of Major until after the capture of Burgoyne at Stillwater. -

Britain's Conciliatory Proposal of 1776, a Study in Futility John Taylor Savage Jr

University of Richmond UR Scholarship Repository Master's Theses Student Research 6-1968 Britain's conciliatory proposal of 1776, A study in futility John Taylor Savage Jr. Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.richmond.edu/masters-theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Savage, John Taylor Jr., "Britain's conciliatory proposal of 1776, A study in futility" (1968). Master's Theses. Paper 896. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research at UR Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of UR Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Project Name: S °''V°'~C,._ ~JoV1.-.._ \ _ I " ' J Date: Patron: Specialist: Oc,~ o7, Co.-. .... or ZD•S ~Tr ""0. ""I Project Description: Hardware Specs: BRITAIN'S CONCILIATORY PROPOSAL OF 1778, A STUDY IN FUTILITY BY JOHN TAYLOR SAVAGE, JR. A THESIS SUBMITI'ED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF RICHMOND IN CANDIDACY FOR IBE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY JUNE, 1968 L:·--:..,:.·:·· -. • ~ ' > ... UNJVE:i1'.':~ i ., ·:.·. ',' ... - \ ;, '.. > TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE PREFACE • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • iv INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • v CHAPTER I. THE DECEMBER TO FEBRUARY PREPARATIONS LEADING TO THE NORTH CONCILIATORY PLAN OF 1778 • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 II. CONCILIATORY PROPOSAL AND COMMISSIONERS: FEBRUARY TO APRIL 1778 • • • • • • • • • • 21 III. THE RESPONSE IN ENGLAND AND FRANCE, FROM MARCH TO MAY, TO BRITAIN'S CONCILIATORY EFFORTS • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 52 IV. AMERICA PREPARES FOR THE RECEPTION OF THE CARLISLE Cu'1MISSION, MARCH TO JUNE 1778. • 70 V. THE JUNE NEGOTIATIONS • • • • • • • • • • • 92 VI. THE SUMMER NEGOTIATIONS: A DISAPPOINT· MENT •••••••• • • • • • • • • • • • 115 VII. -

New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, Vol 18

m<[ o V ^*^°x. „.-.*- ^.•^"•/ *^^'.?^\/ %*^-\*° .*' -'Mi' \/ •«• %/ -^"t *--^/ • ^ o5^^ ^x>^ ' "i'^ ^'} ei» * ^>syS->" • <L^ .-^'' r> * <? . * C (I o V ,0^ •^'^.-J^ .. V Digitized by the Internet Arciiive in 2008 with funding from The Library of Congress http://www.archive.org/details/newyorkgenealog18newy .^^ THE NEW YORK GENEA^ii*li^ND Biographical -^7 DEVOTED TO THE INTERESTS OF AMERICAN GENEALOGY AND BIOGRAPHY. ISSUED QUARTERLY. VOLUME XVIII., 1887. 1WASHIN6V PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY MoTT Memorial Hall, No. 64 Madison Avenue, NEW YORK CITY. PUBLICATION COMMITTEE: Rev. BEVERLEY R. BETTS, Chairman. Dr. SAMUEL S, PURPLE. Gen. JAS. GRANT WILSON, ex-officio. Mr. CHARLES B. MOORE. 4122 Press of J. J. Little & Co. , Astor Place, New York. / ) . J:m}7/zrpif\ IE IRDSKT I^E^. SARfflOJEL !p[a©^®®STjl FIRST 3ISEOP OF SEW-YOSK. Original Portrait in. dve aosaessiou of DT Jain es R.Chi1toii THE NEW YORK Vol. XVIII. NEW YORK, JANUARY, 1887. No. i. SAMUEL PROVOOST, FIRST BISHOP OF NEW YORK.* AN ADDRESS TO THE GENEALOGICAL AND BIOGRAPHICAL SOCIETY. By Gen. Ja.s. Grant Wilson. [With a Portrait of BishoJ> Provoost.) Mr. Chairman, Ladies and Gentlemen : " It is a pleasing fancy which the elder Disraeli has preserved, somewhere, in amber, that portrait-painting had its origin in the inventive fondness of a girl, who traced upon the wall the iirofile of her sleeping lover. It was an outline merely, but love could always fill it up and make it live. It is the most that I can hope to do for my dear, dead brother. But how many there are—the world-wide circle of his friends, his admiring diocese, his attached clergy, the immediate inmates of his heart, the loved ones of his hearth—from whose informing breath it will take life, reality, and beauty." These beautiful words are borrowed from Bishop Doane, of New Jersey, who used them as an introductory paragraph in a memorial of one of Bishop Pro- voost's successors, Jonathan Mayhew Wainwright. -

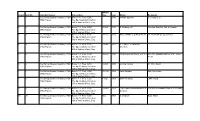

Count Item No. Calendar Header Subsection Month/ Day Year Writer Recipient 1 1 the Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- 1796) Papers

Month/ Count Item No. Calendar Header Subsection Day Year Writer Recipient 1 1 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 1740 William Spencer S. Seabury, Sr. 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 2 2 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 23-Oct 1753 S. Seabury, Sr. Thomas Sherlock, Bp. of London 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 3 3 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 24-Dec 1755 Moses Mathers & Noah Wells Dr. Bearcroft (Sec'y, S.P.G.) 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 4 4 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 23-Jan 1757 S. Clowes, Jr. and Wm. 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Sherlock Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 5 5 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 28-Feb 1757 Philip Bearcroft (Sec'y, S.P.G.) Rev. Mr. Obadiah Mather & Mr. Noah 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Wells Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 6 6 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 30-Oct 1760 Archbp. Secker Dr. Wm. Smith 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 7 7 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 16-Feb 1762 Jane Durham Mrs. Ann Hicks 1796) Papers The Bp. Seabury Collection Gift of Andrew Oliver, Esq. 8 8 The Bishop Samuel Seabury (1729- Boxes 1-3, Files 1-250 4-Sep 1763 Sam'l Seabury John Troup 1796) Papers The Bp.