Darwin Public Hearing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Territory Election 19 August 2020

Barton Deakin Brief: Northern Territory Election 19 August 2020 Overview The Northern Territory election is scheduled to be held on Saturday 22 August 2020. This election will see the incumbent Labor Party Government led by Michael Gunner seeking to win a second term against the Country Liberal Party Opposition, which lost at the 2016 election. Nearly 40 per cent of Territorians have already cast their vote in pre-polling ahead of the ballot. The ABC’s election analyst Antony Green said that a swing of 3 per cent would deprive the Government of its majority. However, it is not possible to calculate how large the swing against the Government would need to be to prevent a minority government. This Barton Deakin brief provides a snapshot of what to watch in this Territory election on Saturday. Current composition of the Legislative Assembly The Territory has a single Chamber, the Legislative Assembly, which is composed of 25 members. Currently, the Labor Government holds 16 seats (64 per cent), the Country Liberal Party Opposition holds two seats (8 per cent), the Territory Alliance holds three seats (12 per cent), and there are four independents (16 per cent). In late 2018, three members of the Parliamentary Labor Party were dismissed for publicly criticising the Government’s economic management after a report finding that the budget was in “structural deficit”. Former Aboriginal Affairs Minister Ken Vowles, Jeff Collins, and Scott McConnell were dismissed. Mr Vowles later resigned from Parliament and was replaced at a by-election in February 2020 by former Richmond footballer Joel Bowden (Australian Labor Party). -

STRONG SCHOOLS STRONG COMMUNITIES President’S Message

Newsletter Issue 2, 2018 NT COGSO President, Tabby Fudge with (from left) Marion Guppy, Deputy Chief Executive Department of Education, Kate Vanderlaan Deputy Commissioner NT Police, Michael Gunner Chief Minister & Police Minister and Eva Lawler Education Minister. NT COGSO staff with Minister for Territory Families Federal Shadow Assistant Minister for Schools Dale Wakefield Andrew Giles MP with NT COGSO President, Tabby Fudge NORTHERN TERRITORY COUNCIL OF GOVERNMENT SCHOOL ORGANISATIONS STRONG SCHOOLS STRONG COMMUNITIES President’s Message I hope your children have had a great Term 2 and you have too! This term NT COGSO have continued to be very busy in lobbying for the return of School Based Police Officers. We have had very productive meetings with key stakeholders, including the Chief Minister Michael Gunner as Minister for Police, Deputy Commissioner NT Police Kate Vanderlaan, Education Minister Eva Lawler and Deputy Chief Executive Department of Education Marion Guppy. We look forward to announcing some very exciting news soon. I would like to thank so many people for the overwhelming support you have given us in our efforts, particularly our wonderful Principals across AEU President Correna Haythorpe with NT COGSO the whole of the Northern Territory, Minister for President, Tabby Fudge Education Eva Lawler, Chief Executive Department The Federal Government is failing our children, of Education Vicki Baylis, NT Children’s fortunately the NT Government are picking up Commissioner Colleen Gwynne, Mr Henry Gray, the pieces and continue to invest in our children MLA Kezia Purick, President Australian Education with additional funding for early childhood. Union NT Jarvis Ryan, Shadow Minister for Education Lia Finocchiaro. -

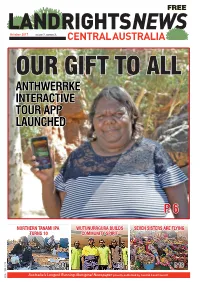

P. 6 Anthwerrke Interactive Tour App Launched

FREE October 2017 VOLUME 7. NUMBER 3. OUR GIFT TO ALL ANTHWERRKE INTERACTIVE TOUR APP LAUNCHED P. 6 NORTHERN TANAMI IPA WUTUNURRGURA BUILDS SEVEN SISTERS ARE FLYING TURNS 10 COMMUNITY SPIRIT P. 14 PG. # P. 4 PG. # P. 19 ISSN 1839-5279ISSN NEWS EDITORIAL Land Rights News Central Bush tenants need NT rental policy overhaul Australia is published by the THE TERRITORY’S Aboriginal Central Land Council three peak organisations have called times a year. on the NT Government to The Central Land Council review its rental policy in remote communities and 27 Stuart Hwy come clean on tenants’ alleged Alice Springs debts following a test case NT 0870 in the Supreme Court that tel: 89516211 highlighted rental payment chaos. www.clc.org.au At stake is whether remote email [email protected] community tenants will have Contributions are welcome to pay millions of dollars worth of rental debts. APO NT’s comments The housing department is pursuing Santa Teresa tenants over rental debts they didn’t know they owed. respond to the test case and SUBSCRIPTIONS reports since at least 2012 that several changes of landlord. half the Santa Teresa tenants that their houses be repaired, the NT Housing Department The department countersued owe an estimated $1 million in that they tell them about all Land Rights News Central has trouble working out who 70 of Santa Teresa’s 100 unpaid rent. this debt. It’s disgraceful.” Australia subscriptions are has paid what rent and when, households who took it to the When Justice Southwood With over 6000 houses $22 per year. -

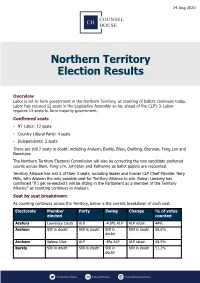

Northern Territory Election Results

24 Aug 2020 Northern Territory Election Results Overview Labor is set to form government in the Northern Territory, as counting of ballots continues today. Labor has secured 12 seats in the Legislative Assembly so far, ahead of the CLP’s 3. Labor requires 13 seats to form majority government. Confirmed seats • NT Labor: 12 seats • Country Liberal Party: 4 seats • Independents: 2 seats There are still 7 seats in doubt, including Araluen, Barkly, Blain, Braitling, Brennan, Fong Lim and Namatjira. The Northern Territory Electoral Commission will also be correcting the two candidate preferred counts across Blain, Fong Lim, Johnston and Katherine as ballot papers are recounted. Territory Alliance has lost 2 of their 3 seats, including leader and former CLP Chief Minister Terry Mills, with Araluen the only possible seat for Territory Alliance to win. Robyn Lambley has confirmed “if I get re-elected I will be sitting in the Parliament as a member of the Territory Alliance” as counting continues in Araluen. Seat by seat breakdown: As counting continues across the Territory, below is the current breakdown of each seat. Electorate Member Party Swing Change % of votes elected counted Arafura Lawrence Costa ALP -4.0% ALP ALP retain 44% Araluen Still in doubt Still in doubt Still in Still in doubt 68.6% doubt Arnhem Selena Uibo ALP -8% ALP ALP retain 48.9% Barkly Still in doubt Still in doubt Still in Still in doubt 51.2% doubt Blain Still in doubt Still in doubt Still in doubt Still in doubt 65% Braitling Still in doubt Still in doubt Still in doubt -

Agenda Item 7.1 REPORT Report No

Agenda Item 7.1 REPORT Report No. 144/17cncl TO: ORDINARY COUNCIL – MONDAY 11 SEPTEMBER 2017 SUBJECT: MAYOR’S REPORT 1. MEETINGS AND APPOINTMENTS 1.1 Lord Mayor of Darwin Katrina Fong Lim 1.2 Kerry Moir and Tony Tapsell, CEO LGANT 1.3 Terry-Ann Maney, Australian Institute of Company Directors 1.4 Stephen Nugent , Advisor to Minister for Tourism and Culture 1.5 Gary Powell, Regional Manager of Central Australia Indigenous Affairs Department, Prime Minister and Cabinet 1.6 Chief Minister Michael Gunner 1.7 Gary Higgins MLA, Leader of the Opposition 1.8 Steve Moore, CEO Barkly Regional Council 1.9 Tony Tapsell, CEO LGANT 1.10 Mayor David O’Loughlin, ALGA President 1.11 Steve Edgington, President Barkly Regional Council 1.12 City of Darwin Lord Mayor Kon Vataskallis 1.13 The Hon. Nicole Manison, NT Treasurer and Richard O’Leary, Advisor 1.14 Alice Springs Town Council – Planning for Great Northern Clean Up 1.15 Ian Coleman, Curator Olive Pink Botanic Garden 1.16 Craig Markham, Paul Tottani, Councillor de Brenni and Dale McIver 1.17 Susan Bradbrook, Governance Institute Australia 1.18 Judith Dixon – Central Australian Development Office 1.19 The Hon. Lauren Moss, Minister for Tourism and Culture 1.20 Chansey Paech MLA, Member for Namatjira 1.21 Litchfield Council Mayor Maree Bredhauer 1.22 Steve Hennessy, Northern Territory Grants Commission 1.23 Boulia Shire Mayor Rick Britton – Outback Way AGM 2. FUNCTIONS ATTENDED 2.1 Red CentreNATS – Volunteers and Officials Welcome, Star of Alice 2.2 Welcome Reception – Red CentreNATS, Alice Springs Convention Centre 2.3 St Philip’s College Musical – Little Women 2.4 Heritage Council Lunch, Mercure Hotel Alice Springs 2.5 Charles Darwin University Campus Industry night 2.6 Reception for Aboriginal Rangers hosted by The Hon. -

Katherine Public Hearing

LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY 11th Assembly Select Committee on Youth Suicides in the NT Public Hearing Transcript 10.15 am, Monday, 6 February 2012 Katherine Town Council Chambers Members: Ms Marion Scrymgour, MLA Chair, Member for Arafura Ms Lynne Walker, MLA, Member for Nhulunbuy Mr Peter Styles, MLA, Member for Sanderson Witnesses: Mr Jim Sullivan The Committee agreed to hear from the NT Early Intervention Pilot Program in camera. NT EARLY INTERVENTION PILOT PROGRAM Ms Jeanette Callaghan, Program Coordinator Ms Lauren Moss, Resource Officer Mr Brent Warren, Superintendent NT Police The Committee resumed the hearing in public. KATHERINE YOUTH INTERAGENCY TASKING & COORDINATION GROUP Snr Constable Daniela Mattiuzzo, Chair Ms Kate Ganley, Secretary Ms Jane Hair, Manager Katherine Top End Mental Health Dr Jill Pettigrew, Psychiatrist Katherine Top End Mental Health Select Committee - Youth Suicides in the Northern Territory – Monday, 6 February 2012 MR JIM SULLIVAN Madam CHAIR: I apologise, Jim, we are starting 20 minutes late. On behalf of the select committee, I welcome you to this public hearing into current and emerging issues of youth suicide in the Northern Territory. I welcome Mr Jim Sullivan to give evidence. Thank you for coming before the committee today. We appreciate you taking the time to speak to the committee and for your submission. This is a formal proceeding of the committee and the protection of parliamentary privilege and your obligation not to mislead the committee apply. A transcript will be made for use of the committee and may be put on the committee’s website. If, at any time during those hearings you are concerned that what you will say should not be made public, you may ask the committee go into a closed session and hear your evidence in private. -

Associated Minutes of Proceedings Report on Statehood Reference

M LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY Legal and Constitutional Affairs Committee Associated Minutes of Proceedings Report on Statehood Reference May 2016 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF THE NORTHERN TERRITORY 12th Assembly Legal & Constitutional Affairs Committee Minutes of Proceedings Meeting No. 1 12pm, Wednesday, 31 October 2012 Litchfield Room Present: Ms Lia Finocchiaro (Chair), Member for Drysdale Ms Kezia Purick, Member for Goyder Mrs Bess Price, Member for Stuart Mr Michael Gunner, Member for Fannie Bay Mr Gerald Mccarthy, Member for Barkly In attendance: Julia Knight, Committee Secretary Russell Keith, Clerk Assistant Committees Lauren Copley Orrock, Administration/Research Officer 1. ELECTION OF CHAIR The Secretary called for nominations for Chair. Ms Purick nominated Ms Finocchiaro as Chair of the Legal & Constitutional Affairs Committee. The motion was seconded by Mrs Price and carried. 2. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF FORMER COMMITTEE MEMBERS The Chair placed on the record her thanks and appreciation to the former Legal & Constitutional Affairs Committee Members, especially the Member for Nightcliff, for their efforts. 3. COIVIMITTEE PROCEDURES (a) Secretariat Support The Committee agreed that hard copies of meeting papers be distributed in the Chamber the morning of future meetings. All papers will also be provided electronically and saved in the LCAC Member's Access folder. It was further agreed that large reports and documents are not to be included in the meeting papers, and can be printed by Members as required. (b) Statements to the Media Mr Gunner moved and Mrs Price seconded That pursuant to Standing Order 274(9d), the Committee authorises the Chair of the Committee to issue media releases and give briefings on matters relating to Legal and Constitutional Affairs and Subordinate Legislation and Publications. -

Theparliamentarian

TheParliamentarian Journal of the Parliaments of the Commonwealth 2015 | Issue Three XCVI | Price £13 Elections and Voting Reform PLUS Commonwealth Combatting Looking ahead to Millenium Development Electoral Networks by Terrorism in Nigeria CHOGM 2015 in Malta Goals Update: The fight the Commonwealth against TB Secretary-General PAGE 150 PAGE 200 PAGE 204 PAGE 206 The Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) Shop CPA business card holders CPA ties CPA souvenirs are available for sale to Members and officials of CPA cufflinks Commonwealth Parliaments and Legislatures by CPA silver-plated contacting the photoframe CPA Secretariat by email: [email protected] or by post: CPA Secretariat, Suite 700, 7 Millbank, London SW1P 3JA, United Kingdom. STATEMENT OF PURPOSE The Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (CPA) exists to connect, develop, promote and support Parliamentarians and their staff to identify benchmarks of good governance and implement the enduring values of the Commonwealth. Calendar of Forthcoming Events Confirmed at 24 August 2015 2015 September 2-5 September CPA and State University of New York (SUNY) Workshop for Constituency Development Funds – London, UK 9-12 September Asia Regional Association of Public Accounts Committees (ARAPAC) Annual Meeting - Kathmandu, Nepal 14-16 September Annual Forum of the CTO/ICTs and The Parliamentarian - Nairobi, Kenya 28 Sept to 3 October West Africa Association of Public Accounts Committees (WAAPAC) Annual Meeting and Community of Clerks Training - Lomé, Togo 30 Sept to 5 October CPA International -

Huge Day of Counting Votes to Determine Fate of Labor and CLP in Tense Territory Election FULL COVERAGE P2-5

VOTE 1 NT ELECTION 2020 SPECIAL EDITIONEVERY vote counts Country freight Monday, August 24, 2020 ntnews.com.au $2.00 30 cents extra Incl GST 11 3 0 Opposition leader Lia Finocchiaro and Chief Minister Michael Gunner Pictures: CHE CHORLEY 2 9 MAD MONDAY Huge day of counting votes to determine fate of Labor and CLP in tense Territory election FULL COVERAGE P2-5 Alliance ‘leadership failure’ Business wants action now TERRITORY Alliance’s wash- and deputy Robyn Lambley is MCLAUGHLIN’S ACTIONS speak louder than challenge for the next four out at the NT Election is being holding on by her teeth in Ara- words and the Territory’s busi- years was just beginning and blamed on a “complete leader- luen. Fong Lim has been lost ness community says it wants the government must move on ship and campaign failure” as too. DARWIN CLEAN plenty of the former, with the quickly from the celebrating. the fledgling party is left with- The NT News understands Gunner Labor Government “Our priorities haven’t out a leader and on the brink of that party members are blam- SWEEP likely to be returned to office. changed,” he said. collapse. ing the loss on Mr Mills and “Now is not the time to have “With everything so much Party leader Terry Mills has Territory Alliance’s campaign a rest,” Chamber of Commerce in the balance, it’s going to be been voted out of Blain as it team of Delia Lawrie and SPORT chief executive Greg Ireland interesting to see how the elec- looks almost certain he will James Lantry. -

Labor-Ind Seats CLP-Ind Seats % % 53.9

Northern Territory Electoral Pendulum 2020 Labor 14 Independent 1 CLP 8 Independent 2 Total 15 Majority 5 Total 10 Labor-Ind Seats CLP-Ind Seats % % 25 24.3 Nightcliff Nelson (CLP) 22.8 25 20 20 23 19.3 Sanderson 21 17.7 Arnhem 19 17.3 Wanguri 17 16.6 Johnston Spillett (CLP) 15.1 23 SWING TO LABOR PARTY TO SWING 15 16.3 Gwoja SWING TO COUNTRY LIBERAL PARTY COUNTRY TO SWING 13 16.1 Mulka (Ind) 11 16.0 Casuarina 15 15 Goyder (Ind) 14.4 21 Araluen (Ind) 12.7 19 10 10 9 9.8 Karama 7 9.6 Fannie Bay 8 8 5 7.9 Drysdale 4 4 3 3 2 1 1 2 Arafura C Katherine (CLP) L 3.6 P 3 - I n Braitling (CLP) d Brennan (CLP) Fong Lim Namatjira (CLP) M Daly (CLP) a 2.7 Barkly (CLP) jo Port Darwin 2.4 r it y 1 2.1 17 1.3 3 1.3 Blain L 1.2 a b 0.4 15 o 0.1 r - 13 I 0.2 nd M 11 53.9% Labor aj 46.1% CLP o 9 r 7 ity 5 KEY 3.6 Swing required to take seat 3 Majority in seats Result of general election, 22 August 2020 Northern Territory : Two-Party Preferred Votes by Division, 22 August 2020 Division Labor Votes % CLP Votes % %Swing to CLP %Swing Needed Winner Arafura 1,388 53.57 1,203 46.43 3.2 3.6 Lawrence Costa (Labor) Araluen⁽a⁾ 1,630 37.35 2,734 62.65 3.0 12.7 Robyn Lambley (Ind) Arnhem⁽b⁾ 1,977 67.61 947 32.39 -5.2 17.7 Selena Uibo (Labor) Barkly 1,717 49.90 1,724 50.10 16.0 0.1 Steve Edgington (CLP) Blain 2,095 50.16 2,082 49.84 -1.5 0.2 Mark Turner (Labor) Braitling 2,141 48.71 2,254 51.29 4.4 1.3 Joshua Burgoyne (CLP) Brennan 2,138 48.81 2,242 51.19 3.8 1.2 Marie-Clare Boothby (CLP) Casuarina 3,035 65.96 1,566 34.04 -4.6 16.0 Lauren Moss (Labor) Daly 1,890 48.79 -

How Well Did You Listen and Learn for Primary Students?

How well did you listen and learn? A quick recap of your visit to the Parliament of the Northern Territory Parliamentary Education Services Department of the Legislative Assembly How many symbols can you remember that are on the Northern Territory’s Coat of Arms? Parliamentary Education Services Department of the Legislative Assembly Parliamentary Education Services Department of the Legislative Assembly Describe the flag of the Northern Territory? Parliamentary Education Services Department of the Legislative Assembly Parliamentary Education Services Department of the Legislative Assembly The number of members in the Legislative Assembly is: a. 35 b. 26 c. 25 Parliamentary Education Services Department of the Legislative Assembly There are 25 members elected for four years. Parliamentary Education Services Department of the Legislative Assembly On what date of the year do we celebrate Self Government? Self Government was granted in 1978 – giving law making power to the Northern Territory Parliament on almost all matters. Parliamentary Education Services Department of the Legislative Assembly July 1, 1978 July 1 Swearing in of NT Ministers by Administrator John England on 1 July 1978. Pictured: John England, Paul Everingham, Ian Tuxworth, Marshall Perron, James Robertson, Roger Steele. Northern Territory Library, Northern Territory Government Photographer Collection, PH0093-0188 Parliamentary Education Services Department of the Legislative Assembly Who is the Chief Minister of the Northern Territory? Parliamentary Education Services -

Australia Needs a Universal Paid Pandemic Leave Scheme to Help Avoid a 2Nd Wave of COVID-19

To: the Australian ‘National Cabinet’: The Right Hon Scott Morrison MP The Hon Steven Marshall MP Prime Minister of Australia Premier of South Australia The Hon Daniel Andrews MP The Hon Peter Gutwein MP Premier of Victoria Premier of Tasmania The Hon Annastacia Palaszczuk MP Andrew Barr MLA Premier of Queensland Chief Minister of the Australian Capital Territory The Hon Gladys Berejiklian MP Premier of New South Wales The Hon Michael Gunner MLA Chief Minister of the Northern Territory The Hon Mark McGowan MP Premier of Western Australia 26 May 2020 Australia needs a universal paid pandemic leave scheme to help avoid a 2nd wave of COVID-19 Our five organizations call upon the National Cabinet, the Federal Government and all state and territory governments to introduce a national paid pandemic leave scheme, administered by employers and funded by government. This is a critical public health intervention to guard against a second wave of infections, and needs to be implemented urgently. Australia has been successful in limiting the spread of SARS-Cov-2 [COVID-19] by implementing a broad range of public health measures. A key aspect of the response has been to implement social distancing and to restrict substantial parts of the economy to reduce the risk of community transmission. As these restrictions begin to ease and Australians return to workplaces, the possibility of increased community transmission grows. It will be essential to maintain extensive testing, and isolation of actual and suspected cases in order to avoid a second wave of infections. Staying home when sick is one of the core messages promoted to the public to reduce the spread of this coronavirus.