4 Discussion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Utility of Genetic Risk Scores in Predicting the Onset of Stroke March 2021 6

DOT/FAA/AM-21/24 Office of Aerospace Medicine Washington, DC 20591 The Utility of Genetic Risk Scores in Predicting the Onset of Stroke Diana Judith Monroy Rios, M.D1 and Scott J. Nicholson, Ph.D.2 1. KR 30 # 45-03 University Campus, Building 471, 5th Floor, Office 510 Bogotá D.C. Colombia 2. FAA Civil Aerospace Medical Institute, 6500 S. MacArthur Blvd Rm. 354, Oklahoma City, OK 73125 March 2021 NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The United States Government assumes no liability for the contents thereof. _________________ This publication and all Office of Aerospace Medicine technical reports are available in full-text from the Civil Aerospace Medical Institute’s publications Web site: (www.faa.gov/go/oamtechreports) Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. Government Accession No. 3. Recipient's Catalog No. DOT/FAA/AM-21/24 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date March 2021 The Utility of Genetic Risk Scores in Predicting the Onset of Stroke 6. Performing Organization Code 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Diana Judith Monroy Rios M.D1, and Scott J. Nicholson, Ph.D.2 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Work Unit No. (TRAIS) 1 KR 30 # 45-03 University Campus, Building 471, 5th Floor, Office 510, Bogotá D.C. Colombia 11. Contract or Grant No. 2 FAA Civil Aerospace Medical Institute, 6500 S. MacArthur Blvd Rm. 354, Oklahoma City, OK 73125 12. Sponsoring Agency name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Office of Aerospace Medicine Federal Aviation Administration 800 Independence Ave., S.W. -

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion Genes Data Set

Supplementary Table 1: Adhesion genes data set PROBE Entrez Gene ID Celera Gene ID Gene_Symbol Gene_Name 160832 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 223658 1 hCG201364.3 A1BG alpha-1-B glycoprotein 212988 102 hCG40040.3 ADAM10 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 10 133411 4185 hCG28232.2 ADAM11 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 11 110695 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 195222 8038 hCG40937.4 ADAM12 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 12 (meltrin alpha) 165344 8751 hCG20021.3 ADAM15 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 15 (metargidin) 189065 6868 null ADAM17 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 17 (tumor necrosis factor, alpha, converting enzyme) 108119 8728 hCG15398.4 ADAM19 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 19 (meltrin beta) 117763 8748 hCG20675.3 ADAM20 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 20 126448 8747 hCG1785634.2 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 208981 8747 hCG1785634.2|hCG2042897 ADAM21 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 21 180903 53616 hCG17212.4 ADAM22 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 22 177272 8745 hCG1811623.1 ADAM23 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 23 102384 10863 hCG1818505.1 ADAM28 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 28 119968 11086 hCG1786734.2 ADAM29 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 29 205542 11085 hCG1997196.1 ADAM30 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 30 148417 80332 hCG39255.4 ADAM33 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 33 140492 8756 hCG1789002.2 ADAM7 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 7 122603 101 hCG1816947.1 ADAM8 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 8 183965 8754 hCG1996391 ADAM9 ADAM metallopeptidase domain 9 (meltrin gamma) 129974 27299 hCG15447.3 ADAMDEC1 ADAM-like, -

The Complex SNP and CNV Genetic Architecture of the Increased Risk of Congenital Heart Defects in Down Syndrome

Downloaded from genome.cshlp.org on September 24, 2021 - Published by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press Research The complex SNP and CNV genetic architecture of the increased risk of congenital heart defects in Down syndrome M. Reza Sailani,1,2 Periklis Makrythanasis,1 Armand Valsesia,3,4,5 Federico A. Santoni,1 Samuel Deutsch,1 Konstantin Popadin,1 Christelle Borel,1 Eugenia Migliavacca,1 Andrew J. Sharp,1,20 Genevieve Duriaux Sail,1 Emilie Falconnet,1 Kelly Rabionet,6,7,8 Clara Serra-Juhe´,7,9 Stefano Vicari,10 Daniela Laux,11 Yann Grattau,12 Guy Dembour,13 Andre Megarbane,12,14 Renaud Touraine,15 Samantha Stora,12 Sofia Kitsiou,16 Helena Fryssira,16 Chariklia Chatzisevastou-Loukidou,16 Emmanouel Kanavakis,16 Giuseppe Merla,17 Damien Bonnet,11 Luis A. Pe´rez-Jurado,7,9 Xavier Estivill,6,7,8 Jean M. Delabar,18 and Stylianos E. Antonarakis1,2,19,21 1–19[Author affiliations appear at the end of the paper.] Congenital heart defect (CHD) occurs in 40% of Down syndrome (DS) cases. While carrying three copies of chromosome 21 increases the risk for CHD, trisomy 21 itself is not sufficient to cause CHD. Thus, additional genetic variation and/or environmental factors could contribute to the CHD risk. Here we report genomic variations that in concert with trisomy 21, determine the risk for CHD in DS. This case-control GWAS includes 187 DS with CHD (AVSD = 69, ASD = 53, VSD = 65) as cases, and 151 DS without CHD as controls. Chromosome 21–specific association studies revealed rs2832616 and rs1943950 as CHD risk alleles (adjusted genotypic P-values <0.05). -

Supplementary Data

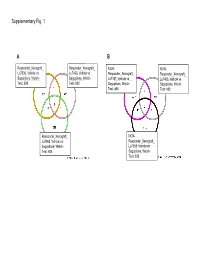

Supplementary Fig. 1 A B Responder_Xenograft_ Responder_Xenograft_ NON- NON- Lu7336, Vehicle vs Lu7466, Vehicle vs Responder_Xenograft_ Responder_Xenograft_ Sagopilone, Welch- Sagopilone, Welch- Lu7187, Vehicle vs Lu7406, Vehicle vs Test: 638 Test: 600 Sagopilone, Welch- Sagopilone, Welch- Test: 468 Test: 482 Responder_Xenograft_ NON- Lu7860, Vehicle vs Responder_Xenograft_ Sagopilone, Welch - Lu7558, Vehicle vs Test: 605 Sagopilone, Welch- Test: 333 Supplementary Fig. 2 Supplementary Fig. 3 Supplementary Figure S1. Venn diagrams comparing probe sets regulated by Sagopilone treatment (10mg/kg for 24h) between individual models (Welsh Test ellipse p-value<0.001 or 5-fold change). A Sagopilone responder models, B Sagopilone non-responder models. Supplementary Figure S2. Pathway analysis of genes regulated by Sagopilone treatment in responder xenograft models 24h after Sagopilone treatment by GeneGo Metacore; the most significant pathway map representing cell cycle/spindle assembly and chromosome separation is shown, genes upregulated by Sagopilone treatment are marked with red thermometers. Supplementary Figure S3. GeneGo Metacore pathway analysis of genes differentially expressed between Sagopilone Responder and Non-Responder models displaying –log(p-Values) of most significant pathway maps. Supplementary Tables Supplementary Table 1. Response and activity in 22 non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) xenograft models after treatment with Sagopilone and other cytotoxic agents commonly used in the management of NSCLC Tumor Model Response type -

Gene Expression Profiling in Pachyonychia Congenita Skin

15 March 2005 Use of Articles in the Pachyonychia Congenita Bibliography The articles in the PC Bibliography may be restricted by copyright laws. These have been made available to you by PC Project for the exclusive use in teaching, scholar- ship or research regarding Pachyonychia Congenita. To the best of our understanding, in supplying this material to you we have followed the guidelines of Sec 107 regarding fair use of copyright materials. That section reads as follows: Sec. 107. - Limitations on exclusive rights: Fair use Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include - (1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes; (2) the nature of the copyrighted work; (3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and (4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work. The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors. -

NRF1) Coordinates Changes in the Transcriptional and Chromatin Landscape Affecting Development and Progression of Invasive Breast Cancer

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 11-7-2018 Decipher Mechanisms by which Nuclear Respiratory Factor One (NRF1) Coordinates Changes in the Transcriptional and Chromatin Landscape Affecting Development and Progression of Invasive Breast Cancer Jairo Ramos [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Clinical Epidemiology Commons Recommended Citation Ramos, Jairo, "Decipher Mechanisms by which Nuclear Respiratory Factor One (NRF1) Coordinates Changes in the Transcriptional and Chromatin Landscape Affecting Development and Progression of Invasive Breast Cancer" (2018). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3872. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3872 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida DECIPHER MECHANISMS BY WHICH NUCLEAR RESPIRATORY FACTOR ONE (NRF1) COORDINATES CHANGES IN THE TRANSCRIPTIONAL AND CHROMATIN LANDSCAPE AFFECTING DEVELOPMENT AND PROGRESSION OF INVASIVE BREAST CANCER A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in PUBLIC HEALTH by Jairo Ramos 2018 To: Dean Tomás R. Guilarte Robert Stempel College of Public Health and Social Work This dissertation, Written by Jairo Ramos, and entitled Decipher Mechanisms by Which Nuclear Respiratory Factor One (NRF1) Coordinates Changes in the Transcriptional and Chromatin Landscape Affecting Development and Progression of Invasive Breast Cancer, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. -

Dark Proteome Database: Studies on Dark Proteins

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 21 January 2019 doi:10.20944/preprints201901.0198.v1 Dark Proteome Database: Studies on Dark Proteins Nelson Perdigão 1,2,* 1 Instituto Superior Técnico, Universidade de Lisboa, 1049-001 Lisbon, Portugal 2 Instituto de Sistemas e Robótica, 1049-001 Lisbon, Portugal. * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The dark proteome as we define it, is the part of the proteome where 3D structure has not been observed either by homology modeling or by experimental characterization in the protein universe. From the 550.116 proteins available in Swiss-Prot (as of July 2016) 43.2% of the Eukarya universe and 49.2% of the Virus universe are part of the dark proteome. In Bacteria and Archaea, the percentage of the dark proteome presence is significantly less, with 12.6% and 13.3% respectively. In this work, we present the map of the dark proteome in Human and in other model organisms. The most significant result is that around 40%- 50% of the proteome of these organisms are still in the dark, where the higher percentages belong to higher eukaryotes (mouse and human organisms). Due to the amount of darkness present in the human organism being more than 50%, deeper studies were made, including the identification of ‘dark’ genes that are responsible for the production of the so-called dark proteins, as well as, the identification of the ‘dark’ organs where dark proteins are over represented, namely heart, cervical mucosa and natural killer cells. This is a step forward in the direction of the human dark proteome. -

Morphology, Behavior, and the Sonic Hedgehog Pathway in Mouse Models of Down Syndrome

MORPHOLOGY, BEHAVIOR, AND THE SONIC HEDGEHOG PATHWAY IN MOUSE MODELS OF DOWN SYNDROME by Tara Dutka A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland July, 2014 © 2014 Tara Dutka All Rights Reserved Abstract Down Syndrome (DS) is caused by a triplication of human chromosome 21 (Hsa21). Ts65Dn, a mouse model of DS, contains a freely segregating extra chromosome consisting of the distal portion of mouse chromosome 16 (Mmu16), a region orthologous to part of Hsa21, and a non-Hsa21 orthologous region of mouse chromosome 17. All individuals with DS display some level of craniofacial dysmorphology, brain structural and functional changes, and cognitive impairment. Ts65Dn recapitulates these features of DS and aspects of each of these traits have been linked in Ts65Dn to a reduced response to Sonic Hedgehog (SHH) in trisomic cells. Dp(16)1Yey is a new mouse model of DS which has a direct duplication of the entire Hsa21 orthologous region of Mmu16. Dp(16)1Yey’s creators found similar behavioral deficits to those seen in Ts65Dn. We performed a quantitative investigation of the skull and brain of Dp(16)1Yey as compared to Ts65Dn and found that DS-like changes to brain and craniofacial morphology were similar in both models. Our results validate examination of the genetic basis for these phenotypes in Dp(16)1Yey mice and the genetic links for these phenotypes previously found in Ts65Dn , i.e., reduced response to SHH. Further, we hypothesized that if all trisomic cells show a reduced response to SHH, then up-regulation of the SHH pathway might ameliorate multiple phenotypes. -

Genome-Wide Analysis of Organ-Preferential Metastasis of Human Small Cell Lung Cancer in Mice

Vol. 1, 485–499, May 2003 Molecular Cancer Research 485 Genome-Wide Analysis of Organ-Preferential Metastasis of Human Small Cell Lung Cancer in Mice Soji Kakiuchi,1 Yataro Daigo,1 Tatsuhiko Tsunoda,2 Seiji Yano,3 Saburo Sone,3 and Yusuke Nakamura1 1Laboratory of Molecular Medicine, Human Genome Center, Institute of Medical Science, The University of Tokyo, Tokyo, Japan; 2Laboratory for Medical Informatics, SNP Research Center, Riken (Institute of Physical and Chemical Research), Tokyo, Japan; and 3Department of Internal Medicine and Molecular Therapeutics, The University of Tokushima School of Medicine, Tokushima, Japan Abstract Molecular interactions between cancer cells and their Although a number of molecules have been implicated in microenvironment(s) play important roles throughout the the process of cancer metastasis, the organ-selective multiple steps of metastasis (5). Blood flow and other nature of cancer cells is still poorly understood. To environmental factors influence the dissemination of cancer investigate this issue, we established a metastasis model cells to specific organs (6). However, the organ specificity of in mice with multiple organ dissemination by i.v. injection metastasis (i.e., some organs preferentially permit migration, of human small cell lung cancer (SBC-5) cells. We invasion, and growth of specific cancer cells, but others do not) analyzed gene-expression profiles of 25 metastatic is a crucial determinant of metastatic outcome, and proteins lesions from four organs (lung, liver, kidney, and bone) involved in the metastatic process are considered to be using a cDNA microarray representing 23,040 genes and promising therapeutic targets. extracted 435 genes that seemed to reflect the organ More than a century ago, Stephen Paget suggested that the specificity of the metastatic cells and the cross-talk distribution of metastases was not determined by chance, but between cancer cells and microenvironment. -

Rodent Models in Down Syndrome Research: Impact and Future Opportunities Yann Herault1,2,3,4,5,*, Jean M

© 2017. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Disease Models & Mechanisms (2017) 10, 1165-1186 doi:10.1242/dmm.029728 REVIEW Rodent models in Down syndrome research: impact and future opportunities Yann Herault1,2,3,4,5,*, Jean M. Delabar5,6,7,8, Elizabeth M. C. Fisher5,9,10, Victor L. J. Tybulewicz5,10,11,12, Eugene Yu5,13,14 and Veronique Brault1,2,3,4 ABSTRACT significantly impairs health and autonomy of affected individuals Down syndrome is caused by trisomy of chromosome 21. To date, a (Khoshnood et al., 2011; Parker et al., 2010). Despite the wide multiplicity of mouse models with Down-syndrome-related features availability of prenatal diagnosis since the mid-1960s (Summers has been developed to understand this complex human et al., 2007) and the introduction of maternal serum screening in chromosomal disorder. These mouse models have been important 1984 (Inglis et al., 2012), the incidence of DS has not necessarily for determining genotype-phenotype relationships and identification decreased (Natoli et al., 2012; Loane et al., 2013; de Graaf et al., of dosage-sensitive genes involved in the pathophysiology of the 2016); in fact, prevalence is going up, largely because of increased condition, and in exploring the impact of the additional chromosome lifespan and maternal age (which is the single biggest risk factor) on the whole genome. Mouse models of Down syndrome have (Sherman et al., 2007; Loane et al., 2013). also been used to test therapeutic strategies. Here, we provide an A core set of features characterises most cases of DS, including overview of research in the last 15 years dedicated to the specific cognitive disabilities, hypotonia (Box 1) at birth and development and application of rodent models for Down syndrome. -

Protective Effects of Propionate Upon the Blood–Brain Barrier

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/170548; this version posted February 7, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Microbiome–host systems interactions: Protective effects of propionate upon 2 the blood–brain barrier 3 4 Lesley Hoyles1*, Tom Snelling1, Umm-Kulthum Umlai1, Jeremy K. Nicholson1, Simon 5 R. Carding2, 3, Robert C. Glen1, 4 & Simon McArthur5* 6 7 1Division of Integrative Systems Medicine and Digestive Disease, Department of 8 Surgery and Cancer, Imperial College London, UK 9 2Norwich Medical School, University of East Anglia, UK 10 3The Gut Health and Food Safety Research Programme, The Quadram Institute, 11 Norwich Research Park, Norwich, UK 12 4Centre for Molecular Informatics, Department of Chemistry, University of Cambridge, 13 Cambridge, UK 14 5Institute of Dentistry, Barts & the London School of Medicine & Dentistry, Blizard 15 Institute, Queen Mary University of London, London, UK 16 17 *Corresponding authors: Lesley Hoyles, [email protected]; Simon 18 McArthur, [email protected] 19 Running title: Propionate affects the blood–brain barrier 20 Abbreviations: ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; ASD, autism spectrum 21 disorder; BBB, blood–brain barrier; CNS, central nervous system; FFAR, free fatty acid 22 receptor; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopaedia of Genes and Genomes; GO, Gene Ontology; 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/170548; this version posted February 7, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. -

Associations Between Human Disease Genes and Overlapping Gene Groups and Multiple Amino Acid Runs

Associations between human disease genes and overlapping gene groups and multiple amino acid runs Samuel Karlin*†, Chingfer Chen*, Andrew J. Gentles*, and Michael Cleary‡ Departments of *Mathematics and ‡Pathology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305 Contributed by Samuel Karlin, October 30, 2002 Overlapping gene groups (OGGs) arise when exons of one gene are Chr 22. Such rearrangements may be mediated by recombination contained within the introns of another. Typically, the two over- events based on region-specific low copy repeats. The DGS lapping genes are encoded on opposite DNA strands. OGGs are region of 22q11.2 is particularly rich with segmental duplications, often associated with specific disease phenotypes. In this report, which can induce deletions, translocations, and genomic insta- we identify genes with OGG architecture and genes encoding bility (4). There are several anomalous sequence features asso- multiple long amino acid runs and examine their relations to ciated with OGGs, including Alu sequences intersecting exons, diseases. OGGs appear to be susceptible to genomic rearrange- pseudogenes occupying introns, and single-exon (intronless) ments as happens commonly with the loci of the DiGeorge syn- genes that often result from a processed multiexon gene. drome on human chromosome 22. We also examine the degree of At least 28 genes in Chr 21 are related to diseases, as conservation of OGGs between human and mouse. Our analyses characterized in the GeneCards database (5), as are 64 genes in suggest that (i) a high proportion of genes in OGG regions are Chr 22. Specific disorders that have been mapped to genes on disease-associated, (ii) genomic rearrangements are likely to occur Chr 21 and that involve OGG structures include: amyotrophic within OGGs, possibly as a consequence of anomalous sequence lateral sclerosis (ALS, Lou Gehrig’s disease), linked to the features prevalent in these regions, and (iii) multiple amino acid GRIK1 ionotrophic kainate 1 glutamate receptor gene at 21q22 runs are also frequently associated with pathologies.