How to Tell Stories to Children and Some Stories to Tell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SHOOT Magazine March/April 2019 Issue

March/April 2019 March/April Chat Room 4 The Road To Emmy Preview Hot Locations 10 4 Spring 2019 DIR Adam McKay Lauren Greenfield Chat Room 18 ECT online.com Series SHOOT ORS Matthew Heineman 8 Ramaa Mosley www. Up-and-Coming Directors 19 Floyd Russ Ridley Scott Spike Jonze Cinematographers & Cameras 22 Top Ten VFX & Animation Chart 26 Top Ten Music Tracks Chart 28 TO GET CONNECTED THE FURTHEST REACHES OF YOUR IMAGINATION ARE CLOSER THAN YOU THINK. With versatile landscapes, experienced film crews and incentivized tax breaks, the only limit to filming in the U.S. Virgin Islands is your imagination. Enjoy up to a 29% tax rebate and up to a 17% transferable tax credit when you film in the USVI. For more opportunities in St.Croix, St. John and St. Thomas, call 340.774.8784 ext. 2243. filmusvi.com DOWNLOAD THE FILM USVI APP: © 2019 U.S. Virgin Islands Department of Tourism USVI19037_9x10.875_SHOOT.indd 1 3/22/19 4:09 PM AGENCY: JWT/Atlanta SPECS: 4C Page Bleed PUB: SHOOT Magazine CLIENT: USVI TRIM: 9” x 10.875” DATE: March/April, 2019 AD#: USVI19037 BLEED: 9.25” x 11.125” HEAD: “The Furthest Reaches of LIVE: 8.5” x 10.375” your Imagination...” Perspectives The Leading Publication For Film, TV & Commercial Production and Post March/April 2019 spot.com.mentary By Robert Goldrich Volume 60 • Number 2 www.SHOOTonline.com EDITORIAL Publisher & Editorial Director Serious Comedy Roberta Griefer 203.227.1699 ext. 701 [email protected] Editor Robert Goldrich Our Up-and-Coming known for its humorous chops, and hope- her feature film, Late Night. -

The Ledger and Times, August 20, 1955

Murray State's Digital Commons The Ledger & Times Newspapers 8-20-1955 The Ledger and Times, August 20, 1955 The Ledger and Times Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/tlt Recommended Citation The Ledger and Times, "The Ledger and Times, August 20, 1955" (1955). The Ledger & Times. 2438. https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/tlt/2438 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Murray State's Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Ledger & Times by an authorized administrator of Murray State's Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. er• amt.!la— 16114 "I‘ss (JGUST 19,, 1955 ited by the stress of Selected As 'A Best All Round Kentucky Co unity Newspaper. slants and vitamins! oxis with "a deficient et" which doesn't lip- id it has no bacteria Carr* Largest Toning." Therefore, the Circulation In The t Make vitamin K on circulation In Tlit thermore its immature City; Largest City; Largest n unable Co transform Circulation In vitamin A. Since thi- Circulation In ster-soluble it can be The County, The County " during the frequent irrheo that affect in- digestive disturbances \ - ionsible far deficienc. s 198 niacin, and ascor United Press IN OUR WKIL YEAR Murray, Ky., Saturday Afternoon, August 20, 1955 MURRAY POPULATION 8,000 Vol. LXRVI No. 40 LBS. FLOODS LEAVE HAVOC IN SIX STATE AREA Capt. Erwin Sea Captain Stays Red China Uneasy Death Toll Nears 100 Mark As On Damaged Ship Over Statements By Freed Airmen WICK, Scotland, Aug. -

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119

INGO GILDENHARD Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary CICERO, PHILIPPIC 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119 Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary Ingo Gildenhard https://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2018 Ingo Gildenhard The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt the text and to make commercial use of the text providing attribution is made to the author(s), but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work. Attribution should include the following information: Ingo Gildenhard, Cicero, Philippic 2, 44–50, 78–92, 100–119. Latin Text, Study Aids with Vocabulary, and Commentary. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2018. https://doi. org/10.11647/OBP.0156 Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https:// www.openbookpublishers.com/product/845#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/4.0/ All external links were active at the time of publication unless otherwise stated and have been archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine at https://archive.org/web Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www. -

The Ledger and Times, February 5, 1955

Murray State's Digital Commons The Ledger & Times Newspapers 2-5-1955 The Ledger and Times, February 5, 1955 The Ledger and Times Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/tlt Recommended Citation The Ledger and Times, "The Ledger and Times, February 5, 1955" (1955). The Ledger & Times. 2274. https://digitalcommons.murraystate.edu/tlt/2274 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers at Murray State's Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Ledger & Times by an authorized administrator of Murray State's Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ,••••••••••r ••••••pr•••••• 11.•••••••• n/•••••./..•••••••20001,0•..1.0011.1111.4.1111101.1.1110MOn.a. Selected As A Rest All Round Rentucky Community Newspaper tree down Tree see-- )55 Largest Largest Circulation In The an lation In The Mrs ity; Largest City; Largest Ida. EK irculation In Circulation In 17c 11 The County den 10e The County Mrs. 7c igh 30c ithour ited Press IN OUR 76th YEAR Niurray, Ky., Saturday Afternoon, February 5, 1955 . MURRAY POPULATION 8,000 Vol. LX-5(VI No. 31 IN INCREASE ASSOCIATION IS FORMED eadv To.Seek China Coastal Islands Have -SUPPLIES FOR FORMOSA LOADED AT OKINAWA Dr. Kopperud Heads Group ecision With Been Fought For Many Times Here To Increase Rainfall as temporary chairman if thw.Cal- - By WILLIAM MILLER and hundreds of yards of rein- A farm meeting eva, held in the ussia, Report loway County Rain Increase Assoc- United Press Staff t'orrespondent forced cor.crete underground tun- courthouse on Thursdey afternoon ex- iation at the meeting. -

Toand Television Irrom June 25

TOAND TELEVISION IRROM JUNE 25 1tVeledrillt 44 111vot-ir Percy MILTON BERLE GRACIE ALLEN ')N McNEILL RALPH EDWARDS BIG SISTER LANNY ROSS filter Winchell Contest Winners - i (o+1) Vie, fodLut, tiA9ti otcuut SKIN -SAFE SOLITAIRI The only founda- tion- and -pawder make -up with clinicol evidence- certified by leading skin specialists from coast to coast -that it DOES NOT CLOG PORES, cause skin texture change or inflammation of hair follicle ar other gland opening. Na other liquid, powder, creom or cake "founda- tion" moke -up offers such positive proof of safety for your skin. biopsy- specimen flown by Cell Chapman. Jewels by Seaman-Schepps. See the loveliest you that you've ever seen -the minute you use Solitair cake make -up. Gives your skin a petal- smooth appearance -so flatteringly natural that you look as if you'd been born with it! Solitair is entirely different- a special feather -weight formula. Clings longer. Outlasts powder. Hides little skin faults -yet never feels mask -like, never looks "made -up." Like finest face creams, Solitair contains Lanolin to protect against dryness. Truly -you'll be lovelier with this make -up that millions prefer. No better quality. Only $1.00. Cake Make -Up * Fashion -Point Lipstick Seven new fashion -right shades Yes -the first and only lipstick with point actually shaped to curve of your lips. Applies color quicker, easier, more evenly. New, exciting "Dreamy Pink" shade - and six new reds. So creamy smooth- contains Lanolin -stays on so long. Exquisite case. $1.00 *Slanting cap with red enameled circle identifies the famous 'Fashion -Point and shows you exact (¡orí*iwnn tameGm color of lipstick inside. -

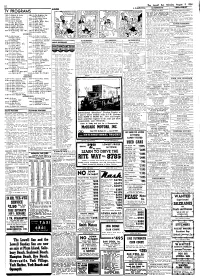

RITE WAY 8783 Hard Top Coupe 1 University Press to Honor the To

The Lowell Sun Monday August 9 1954 12 AUTOMOTIVE EMPLOYMENT K.ONDM A Fritndly Child AUTOS FOR 8AIE SITUATION WANTED—FEMALE 1 IT STARTED TO RAIN, M HOW CAN 1 WOWK flNOVOUR LITTLE NOW I CAN - TV PROGRAMS SO I INVITED THEM AUTO iUANH «t luw. uioiiey-aeirlnK ralea ILL MI.MI I 1)11 J WITH ALL, THAT ,FRIENDS AND PLAV REALLV GET THE TO COME IN AND •"eat eerrlce Uiwell Inalliullot) fur bi»- IID.lllv ll.MI.V. TKL. COMMOTION ? [ OUTDOORS, COOKIE [ HOUSE CLEANED ln«>. alaln Otrico on HbMiura tltrooi Boltort Q. t>wln 4:00—7—The Brighter l)«y PLAV Hlclilandi Office «l Cuppka Huuaro Me for Dial D 2:15—•»—C'lilhl Brlwvliir —4—At l''our on 4 TIiTrnTv~iM i iioor Keii.in. Kiccjiiiiui 4:1,%—7—The Secret Storm nl cai Has Meiciilnullo ililve, cmtoii 2:3<f—7—llouw I'»rty H.lliY KlTTKlt delllllU'.-ueek-elld!!. lloiceri 4:30—7—Sonif Shop Inicniir. lu'iiti-r and oilier cMra*. AlmoM Hull Minli-nl. lllKlilaniN •" M'tMland.. I!:45—1—Arch Mi-duimM in.r nev, |i:i!Ti. IIUIP MOTORS. HOD Illlll ^-THI'K. —4—Betty White Show Cm limn St. Ulnl MIL 0|irli '.< a. III. —7—The Ble I'ayoff •1:3,1—7—Song Shop ANNOUNCEMENTS 3:00—i—One.Man's Family 4:4(1—7—Song Shop Kdltll 1919 — Cluh Cuiijie. }i-c>llliilci, R A II. llii'id condition. Must sell. Best oiler 3:lf>—4—Golden Windows 6:00—7—Western Him ANNOUNCEMENT 8:30—4—Bride anil Groom —4—Pinky 1-ee JEltccio Ml.'.U—Shillon Wiinm. -

Princess Stories Easy Please Note: Many Princess Titles Are Available Under the Call Number Juvenile Easy Disney

Princess Stories Easy Please note: Many princess titles are available under the call number Juvenile Easy Disney. Alsenas, Linas. Princess of 8th St. (Easy Alsenas) A shy little princess, on an outing with her mother, gets a royal treat when she makes a new friend. Andrews, Julie. The Very Fairy Princess Takes the Stage. (Easy Andrews) Even though Gerry is cast as the court jester instead of the crystal princess in her ballet class’s spring performance, she eventually regains her sparkle and once again feels like a fairy princess. Barbie. Barbie: Fairytale Favorites. (Easy Barbie) Barbie: Princess charm school -- Barbie: a fairy secret -- Barbie: a fashion fairytale -- Barbie in a mermaid tale -- Barbie and the three musketeers. Child, Lauren. The Princess and the Pea in Miniature : After the Fairy Tale by Hans Christian Andersen. (Easy Child) Presents a re-telling of the well-known fairy tale of a young girl who feels a pea through twenty mattresses and twenty featherbeds and proves she is a real princess. Coyle, Carmela LaVigna . Do Princesses Really Kiss Frogs? (Easy Coyle) A young girl takes a hike with her father, asking many questions along the way about what princesses do. Cuyler, Margery. Princess Bess Gets Dressed. (Easy Cuyler) A fashionably dressed princess reveals her favorite clothes at the end of a busy day. Disney. 5-Minute Princess Stories. (Easy Disney) Magical tales about princesses from different Walt Disney movies. Disney. Princess Adventure Stories. (Easy Disney) A collection of stories from favorite Disney princesses. Edmonds, Lyra. An African Princess. (Easy Edmonds) Lyra and her parents go to the Caribbean to visit Taunte May, who reminds her that her family tree is full of princesses from Africa and around the world. -

15Th Annual Carolyn and Norwood Thomas Undergraduate Research and Creativity Expo

15th Annual Carolyn and Norwood Thomas Undergraduate Research and Creativity Expo 2021 a unit within the University Teaching & Learning Commons utlc.uncg.edu/ursco Preston Lee Phillips Jr, Ph.D. Director Adrienne W. Middlebrooks Business Officer Traci Miller, MSA MARC Program: Academic Enhancement Coordinator Maizie Plumley Graduate Assistant Ali Ramirez Garibay Undergraduate Assistant URSCO is a unit within the University Teaching and Learning Commons Undergraduate Research, Scholarship and Creativity Office ~ Leadership Committee ~ Lee Phillips, Ph.D. URSCO Director Amy Adamson, Ph.D. College of Arts and Sciences Heather Holian, Ph.D. College of Visual and Performing Arts Jamie Schissel, Ph.D. and Sara Heredia, Ph.D. School of Education Kathleen Williams, Ph.D. School of Health and Human Sciences Angela Bolte, Ph.D. Lloyd International Honors College George R. Still III Student Affairs Tiffany Henry University Libraries University Teaching and Learning Commons 130 Shaw Hall Greensboro, NC 27402-6170 336.334.4776 April 19, 2021 Dear Students, Colleagues, and Guests, I would like to welcome you to the 15th Annual Carolyn and Norwood Thomas Undergraduate Research and Creativity Expo and the 2nd Virtual Undergraduate Research and Creativity Expo at UNCG. As we have all worked to navigate our lives and learning through the adjusted approaches required by this ongoing pandemic, we have seen an incredible commitment of the UNCG community to learning through research and creative inquiry. This year, we are thrilled to accept 223 presentations by more than 239 students, working with 90 mentors, and representing 29 academic departments/programs. This year includes another distinction as we have partnered with the School of Art to cohost a portion of the Senior BFA Exhibitions. -

Preacher's Magazine Volume 23 Number 04 D

Olivet Nazarene University Digital Commons @ Olivet Preacher's Magazine Church of the Nazarene 7-1-1948 Preacher's Magazine Volume 23 Number 04 D. Shelby Corlett E( ditor) Olivet Nazarene University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/cotn_pm Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, International and Intercultural Communication Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Missions and World Christianity Commons, and the Practical Theology Commons Recommended Citation Corlett, D. Shelby (Editor), "Preacher's Magazine Volume 23 Number 04" (1948). Preacher's Magazine. 238. https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/cotn_pm/238 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Church of the Nazarene at Digital Commons @ Olivet. It has been accepted for inclusion in Preacher's Magazine by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Olivet. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The PREACHERS MAGAZINE JULY-AUGUST, 1948 W e Would See Jesus! “ We would see Jesus,” said the men who came To worship at the feast so long ago; And still the cry is heard the world around. In every land wherever man is found; "W e would see Jesus, we would see and know.” "W e would see Jesus,” say the worldly throng; "W ould see Him in the lives of you who say You follow Him and worship at His feet, And spend your lives in service glad and sweet. And keep His blest commandments every day!” "W e would see Jesus!” Oh, the yearning cry Of countless thousands lost in misery! Then, blessed Master, dwell so close within That I shall never yield my heart to sin; So shall Thy beauty glow for all to see. -

SD: STOP!! First Objection

Situated south of Dresden, this bizarre landscape Elbe Sandstone Mountains was a rich source of motifs for almost all the 1789-1849 German romantics. Their images shape our Video approx. 50 min romantic view today of the time between the Stephan Dillemuth, 1994 French revolution and the March revolution in Germany. TV Studio, a presenter enters the stage through In a journey through film and text, leading up to an opening in a rose-strewn trellis, flowers in his an Elbe Sandstone Mountains trip, we are hand. An artificial rainbow in the background, an confronted with our own projections. antique sculpture of a woman's head on a pillar Was romanticism political or was politics in the foreground. The presenter places the romantic? And what do Journey to the Inside, flowers on the head. Biedermeier and German revolution mean to us today – in 1995? Presenter: Good evening ladies and gentlemen. As part of this regular cultural programme on the Presenter turns his back on the audience and with Hamburg Free Channel we are showing you today a scream jumps over the fence and falls a long at the usual hour a video film by the Cologne way down behind the trellis. artist Stephan Dillemuth about the Elbe Sandstone Cut to a singing child in a blue dress with a Mountains. microphone in her hand. Location shot. Girl: of a group. Put this sentence of mine in real terms And then I heard a voice ring out and you find that every clause has killed its men. Deep down in me, Which in a moment rapt away It needed four years to be translated into physical My memory.. -

Breaking the Magic Spell: Radical Theories of Folk and Fairy Tales

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Folklore Anthropology 7-5-2002 Breaking the Magic Spell: Radical Theories of Folk and Fairy Tales Jack Zipes Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Zipes, Jack, "Breaking the Magic Spell: Radical Theories of Folk and Fairy Tales" (2002). Folklore. 15. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_folklore/15 Breaking the Magic Spell Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright O 1979 by Jack Zipes Published 2002 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. - Editorial and Sales Ofices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Zipes, Jack Breaking the magic spell. 1. Tales, European-History and criticism. 2. Literature and society. I. Title ISBN-10: 0-8131-9030-4 (paper) ISBN-13: 978-0-8131-9030-3 This book is printed on acid-free recycled paper meeting the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence in Paper for Printed Library Materials. -

The Tales of the Grimm Brothers in Colombia: Introduction, Dissemination, and Reception

Wayne State University Wayne State University Dissertations 1-1-2012 The alest of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception Alexandra Michaelis-Vultorius Wayne State University, Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.wayne.edu/oa_dissertations Part of the German Literature Commons, and the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Michaelis-Vultorius, Alexandra, "The alet s of the grimm brothers in colombia: introduction, dissemination, and reception" (2012). Wayne State University Dissertations. Paper 386. This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@WayneState. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wayne State University Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@WayneState. THE TALES OF THE GRIMM BROTHERS IN COLOMBIA: INTRODUCTION, DISSEMINATION, AND RECEPTION by ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of Wayne State University, Detroit, Michigan in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2011 MAJOR: MODERN LANGUAGES (German Studies) Approved by: __________________________________ Advisor Date __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ __________________________________ © COPYRIGHT BY ALEXANDRA MICHAELIS-VULTORIUS 2011 All Rights Reserved DEDICATION To my parents, Lucio and Clemencia, for your unconditional love and support, for instilling in me the joy of learning, and for believing in happy endings. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This journey with the Brothers Grimm was made possible through the valuable help, expertise, and kindness of a great number of people. First and foremost I want to thank my advisor and mentor, Professor Don Haase. You have been a wonderful teacher and a great inspiration for me over the past years. I am deeply grateful for your insight, guidance, dedication, and infinite patience throughout the writing of this dissertation.