Ali Salam, from Pierre Trudeau to Justin Trudeau

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liberalism, Social Democracy, and Tom Kent Kenneth C

Liberalism, Social Democracy, and Tom Kent Kenneth C. Dewar Journal of Canadian Studies/Revue d'études canadiennes, Volume 53, Number/numéro 1, Winter/hiver 2019, pp. 178-196 (Article) Published by University of Toronto Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/719555 Access provided by Mount Saint Vincent University (19 Mar 2019 13:29 GMT) Journal of Canadian Studies • Revue d’études canadiennes Liberalism, Social Democracy, and Tom Kent KENNETH C. DEWAR Abstract: This article argues that the lines separating different modes of thought on the centre-left of the political spectrum—liberalism, social democracy, and socialism, broadly speaking—are permeable, and that they share many features in common. The example of Tom Kent illustrates the argument. A leading adviser to Lester B. Pearson and the Liberal Party from the late 1950s to the early 1970s, Kent argued for expanding social security in a way that had a number of affinities with social democracy. In his paper for the Study Conference on National Problems in 1960, where he set out his philosophy of social security, and in his actions as an adviser to the Pearson government, he supported social assis- tance, universal contributory pensions, and national, comprehensive medical insurance. In close asso- ciation with his philosophy, he also believed that political parties were instruments of policy-making. Keywords: political ideas, Canada, twentieth century, liberalism, social democracy Résumé : Cet article soutient que les lignes séparant les différents modes de pensée du centre gauche de l’éventail politique — libéralisme, social-démocratie et socialisme, généralement parlant — sont perméables et qu’ils partagent de nombreuses caractéristiques. -

The Politics of Innovation

The Future City, Report No. 2: The Politics of Innovation __________________ By Tom Axworthy 1972 __________________ The Institute of Urban Studies FOR INFORMATION: The Institute of Urban Studies The University of Winnipeg 599 Portage Avenue, Winnipeg phone: 204.982.1140 fax: 204.943.4695 general email: [email protected] Mailing Address: The Institute of Urban Studies The University of Winnipeg 515 Portage Avenue Winnipeg, Manitoba, R3B 2E9 THE FUTURE CITY, REPORT NO. 2: THE POLITICS OF INNOVATION Published 1972 by the Institute of Urban Studies, University of Winnipeg © THE INSTITUTE OF URBAN STUDIES Note: The cover page and this information page are new replacements, 2015. The Institute of Urban Studies is an independent research arm of the University of Winnipeg. Since 1969, the IUS has been both an academic and an applied research centre, committed to examining urban development issues in a broad, non-partisan manner. The Institute examines inner city, environmental, Aboriginal and community development issues. In addition to its ongoing involvement in research, IUS brings in visiting scholars, hosts workshops, seminars and conferences, and acts in partnership with other organizations in the community to effect positive change. ' , I /' HT 169 C32 W585 no.Ol6 c.l E FUTURE .·; . ,... ) JI Report No.2 The Politics of Innovation A Publication of THE INSTITUTE OF URBAN STUDIES University of Winnipeg THE FUTUKE CITY Report No. 2 'The Politics of Innovation' by Tom Axworthy with editorial assistance from Professor Andrew Quarry and research assistance from Mr. J. Cassidy, Mr. Paul Peterson, and Judy Friedrick. published by Institute of Urban Studies University of Winnipeg FOREWORD This is the second report published by the Institute of Urban Studies on the new city government scheme in Winnipeg. -

Alternative North Americas: What Canada and The

ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS What Canada and the United States Can Learn from Each Other David T. Jones ALTERNATIVE NORTH AMERICAS Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars One Woodrow Wilson Plaza 1300 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20004 Copyright © 2014 by David T. Jones All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of author’s rights. Published online. ISBN: 978-1-938027-36-9 DEDICATION Once more for Teresa The be and end of it all A Journey of Ten Thousand Years Begins with a Single Day (Forever Tandem) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Borders—Open Borders and Closing Threats .......................................... 12 Chapter 2 Unsettled Boundaries—That Not Yet Settled Border ................................ 24 Chapter 3 Arctic Sovereignty—Arctic Antics ............................................................. 45 Chapter 4 Immigrants and Refugees .........................................................................54 Chapter 5 Crime and (Lack of) Punishment .............................................................. 78 Chapter 6 Human Rights and Wrongs .................................................................... 102 Chapter 7 Language and Discord .......................................................................... -

What Role Does Type of Sponsorship Play in Early Integration Outcomes? Syrian Refugees Resettled in Six Canadian Cities

Document generated on 09/25/2021 9:34 a.m. Refuge Canada's Journal on Refugees Revue canadienne sur les réfugiés What Role Does Type of Sponsorship Play in Early Integration Outcomes? Syrian Refugees Resettled in Six Canadian Cities Michaela Hynie, Susan McGrath, Jonathan Bridekirk, Anna Oda, Nicole Ives, Jennifer Hyndman, Neil Arya, Yogendra B. Shakya, Jill Hanley and Kwame McKenzie Private Sponsorship in Canada Article abstract Volume 35, Number 2, 2019 There is little longitudinal research that directly compares the effectiveness of Canada’s Government-Assisted Refugee (GAR) and Privately Sponsored Refugee URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1064818ar (PSR) Programs that takes into account possible socio-demographic differences DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1064818ar between them. This article reports findings from 1,921 newly arrived adult Syrian refugees in British Columbia, Ontario, and Quebec. GARs and PSRs See table of contents differed widely on several demographic characteristics, including length of time displaced. Furthermore, PSRs sponsored by Groups of 5 resembled GARs more than other PSR sponsorship types on many of these characteristics. PSRs also had broader social networks than GARs. Sociodemographic differences Publisher(s) and city of residence influenced integration outcomes, emphasizing the Centre for Refugee Studies, York University importance of considering differences between refugee groups when comparing the impact of these programs. ISSN 0229-5113 (print) 1920-7336 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Hynie, M., McGrath, S., Bridekirk, J., Oda, A., Ives, N., Hyndman, J., Arya, N., Shakya, Y., Hanley, J. & McKenzie, K. (2019). What Role Does Type of Sponsorship Play in Early Integration Outcomes? Syrian Refugees Resettled in Six Canadian Cities. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CHRETIEN LEGACY Introduction .................................................. i The Chr6tien Legacy R eg W hitaker ........................................... 1 Jean Chr6tien's Quebec Legacy: Coasting Then Stickhandling Hard Robert Y oung .......................................... 31 The Urban Legacy of Jean Chr6tien Caroline Andrew ....................................... 53 Chr6tien and North America: Between Integration and Autonomy Christina Gabriel and Laura Macdonald ..................... 71 Jean Chr6tien's Continental Legacy: From Commitment to Confusion Stephen Clarkson and Erick Lachapelle ..................... 93 A Passive Internationalist: Jean Chr6tien and Canadian Foreign Policy Tom K eating ......................................... 115 Prime Minister Jean Chr6tien's Immigration Legacy: Continuity and Transformation Yasmeen Abu-Laban ................................... 133 Renewing the Relationship With Aboriginal Peoples? M ichael M urphy ....................................... 151 The Chr~tien Legacy and Women: Changing Policy Priorities With Little Cause for Celebration Alexandra Dobrowolsky ................................ 171 Le Petit Vision, Les Grands Decisions: Chr~tien's Paradoxical Record in Social Policy M ichael J. Prince ...................................... 199 The Chr~tien Non-Legacy: The Federal Role in Health Care Ten Years On ... 1993-2003 Gerard W . Boychuk .................................... 221 The Chr~tien Ethics Legacy Ian G reene .......................................... -

Citizenship Revocation in the Mainstream Press: a Case of Re-Ethni- Cization?

Citizenship RevoCation in the MainstReaM pRess: a Case of Re-ethni- Cization? elke WinteR ivana pRevisiC Abstract. Under the original version of the Strengthening Canadian Citizenship Act (2014), dual citizens having committed high treason, terrorism or espionage could lose their Canadian citizenship. In this paper, we examine how the measure was dis- cussed in Canada’s mainstream newspapers. We ask: who/what is seen as the target of citizenship revocation? What does this tell us about the direction that Canadian more often critical than supportive of the citizenship revocation provision. However, the press ignored the involvement of non-Muslim, white, Western-origin Canadians in terrorist acts and interpreted the measure as one that was mostly affecting Canadian Muslims. Thus, despite advocating for equal citizenship in principle, in their writing and reporting practice, Canadian newspapers constructed Canadian Muslims as sus- picious and less Canadian nonetheless. Keywords: Muslim Canadians; Citizenship; Terrorism; Canada; Revocation Résumé: Au sein de la version originale de la Loi renforçant la citoyenneté cana- dienne (2014), les citoyens canadiens ayant une double citoyenneté et ayant été condamnés pour haute trahison, pour terrorisme ou pour espionnage, auraient pu se faire révoquer leur citoyenneté canadienne. Dans cet article, nous étudions comment ce projet de loi fut discuté au sein de la presse canadienne. Nous cherchons à répondre à deux questions: Qui/quoi est perçu comme pouvant faire l’objet d’une révocation de citoyenneté? En quoi cela nous informe-t-il sur les orientations futures de la citoy- enneté canadienne? Nos résultats démontrent que les journaux canadiens sont plus critiques à l’égard de la révocation de la citoyenneté que positionnés en sa faveur. -

Why Virtue Is Not Reward Enough

ON BEING AN ALLY: WHY VIRTUE IS NOT REWARD ENOUGH Thomas S. Axworthy The Canadian diplomat and scholar John Holmes once observed: “Coping with the fact of the USA is and has always been an essential fact of being Canadian. It has formed us just as being an island formed Britain.” Tom Axworthy, a noted practitioner of Canada-US relations and studies as principal secretary to Prime Minister Trudeau and Mackenzie King Chair at Harvard University, suggests that “we need a constructive relationship with the US, not to please them but to promote ourselves.” He proposes “4 Ds” to get Canada back on the Washington radar screen: “defence, development, diplomacy and democracy.” Canada’s defence deficit is all too apparent, while our development spending is a paltry 0.25 percent of output. In diplomacy Canada pales beside the effort of Mexico’s 63 consulates in the US. Afghanistan is one country where all these components, as well as the institution- building of democracy, all come into play, and can not only enhance Canada’s standing in the international community, but directly benefit our relations with the US. “Being an ally means that one is neither a sycophant nor a freeloader,” Axworthy says. “You are, instead, a partner, and partnership means sharing the load.” Comme le disait en substance le diplomate canadien John Holmes : le voisinage des États-Unis a toujours été et reste indissociable de l’identité canadienne, tout comme l’identité britannique est indissociable de l’insularité du Royaume-Uni. Selon Tom Ax w o r t h y , ancien secrétaire principal de Pierre Elliott Trudeau et titulaire de la chaire Mackenzie King à l’université Harvard, nous devons ainsi entretenir des liens constructifs avec les États-Unis non pour leur plaire mais pour promouvoir nos intérêts. -

In the National Interest: Canadian Foreign Policy and the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, 1909–2009

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2011 In the National Interest: Canadian Foreign Policy and the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, 1909–2009 University of Calgary Press Donaghy, G., & Carroll, M. (Eds.). (2011). In the National Interest: Canadian Foreign Policy and the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, 1909-2009. Calgary, Alberta, Canada: University of Calgary Press. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/48549 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 Unported Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com IN THE NATIONAL INTEREST Canadian Foreign Policy and the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade, 1909–2009 Greg Donaghy and Michael K. Carroll, Editors ISBN 978-1-55238-561-6 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

Ridrissue5 1..74

First Session Première session de la Forty-second Parliament, 2015-16 quarante-deuxième législature, 2015-2016 Proceedings of the Standing Délibérations du Comité Senate Committee on sénatorial permanent des Human Rights Droits de la personne Chair: Président : The Honourable JIM MUNSON L'honorable JIM MUNSON Wednesday, May 11, 2016 Le mercredi 11 mai 2016 Wednesday, May 18, 2016 Le mercredi 18 mai 2016 Issue No. 5 Fascicule nº 5 Consideration of a draft agenda (future business) Étude d'un projet d'ordre du jour (travaux futurs) and et First and second meetings: Première et deuxième réunions : Study on steps being taken to facilitate the integration of Étude sur les mesures prises pour faciliter l'intégration des newly-arrived Syrian refugees and to address the challenges réfugiés syriens nouvellement arrivés et les aider à they are facing, including by the various levels of surmonter les difficultés qu'ils vivent, notamment par les government, private sponsors and non-governmental divers ordres de gouvernement, les répondants du secteur organizations privé et les organismes non gouvernementaux APPEARING: COMPARAÎT: The Honourable John McCallum, P.C., M.P., Minister of L'honorable John McCallum, C.P., député, ministre de Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship l'Immigration, des Réfugiés et de la Citoyenneté THE THIRD REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE LE TROISIÈME RAPPORT DU COMITÉ (Special Study Budget (Integration of Newly-arrived (Budget pour étude spéciale (Intégration des réfugiés Syrian Refugees) 2016-2017) syriens nouvellement arrivés) 2016-2017) WITNESSES: TÉMOINS : (See back cover) (Voir à l'endos) 52579-52611 STANDING SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMITÉ SÉNATORIAL PERMANENT DES HUMAN RIGHTS DROITS DE LA PERSONNE The Honourable Jim Munson, Chair Président : L'honorable Jim Munson The Honourable Salma Ataullahjan, Deputy Chair Vice-présidente : L'honorable Salma Ataullahjan and et The Honourable Senators: Les honorables sénateurs : Andreychuk Hubley Andreychuk Hubley * Carignan, P.C. -

2003 Spring Issue

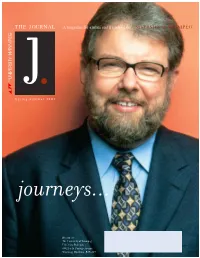

THE JOURNAL A magazine for alumni and friends of the UNIVERSITY OF WINNIPEG Spring/Summer 2003 journeys... Return to: The University of Winnipeg University Relations ??. 4W21-515 Portage Avenue THE JOURNAL Winnipeg, Manitoba R3B 2E9 T HE U NIVERSITY OF W INNIPEG The University of Winnipeg’s Board of Regents is pleased to announce the establishment of THE UNIVERSITY OF WINNIPEG FOUNDATION The University of Winnipeg Foundation is dedicated to fundraising and asset stewardship in support of the mission and vision of The University of Winnipeg. INTRODUCING Susan A. Thompson, Chief Executive Officer The University of Winnipeg Foundation Former Mayor of the City of Winnipeg Former Consul General of Canada, Minneapolis Class of ’67 Collegiate & Class of ’71 The University of Winnipeg FOR FURTHER INFORMATION: Director of Advancement Janet Walker | tel: (204) 786-9148 | email: [email protected] www.uwinnipeg.ca features. COVER STORY: THE ROAD FROM TRANSCONA TO PARLIAMENT HILL | 4 Bill Blaikie on the twists and turns of his political career CULTIVATING A NEW WAY OF THINKING | 8 UWinnipeg alumna Ann Waters-Bayer and the sociology of agriculture ANDY LOCKERY | 14 From the UK to UWinnipeg, the career path of professor Andy Lockery CKUW | 16 The incredible journey from PA system to homegrown radio ARIEL ZYLBERMAN | 18 Philosopher,teacher,and student of life- UWinnipeg’s newest Rhodes scholar content. 4. 14. departments. 16. 18. EDITOR’S NOTE | 2 VOLUNTEER OPPORTUNITIES | 6 UPDATE YOUR ALUMNI RECORD | 6 UPDATE U | 7 ALUMNI NEWS BRIEFS | 10 ALUMNI AUTHORS | 13 CLASS ACTS | 20 IN MEMORIAM | 23 Editorial Team: Editor, Lois Cherney ’84; Communications Officer, Paula Denbow; Managing Editor, Annette Elvers ’93; THE JOURNAL Director of Communications, Katherine Unruh; and, Director of Advancement, Janet Walker ’78 | Alumni Council Communications Team: Thamilarasu Subramaniam ’96 (Team Leader); Jane Dick ’72 (Asst. -

Citizenship Revocation in the Mainstream Press: a Case of Re-Ethni- Cization?

CITIZENSHIP REVOCATION IN THE MAINSTREAM PRESS: A CASE OF RE-ETHNI- CIZATION? ELKE WINTER IVANA PREVISIC Abstract. Under the original version of the Strengthening Canadian Citizenship Act (2014), dual citizens having committed high treason, terrorism or espionage could lose their Canadian citizenship. In this paper, we examine how the measure was dis- cussed in Canada’s mainstream newspapers. We ask: who/what is seen as the target of citizenship revocation? What does this tell us about the direction that Canadian citizenship is moving towards? Our findings show that Canadian newspapers were more often critical than supportive of the citizenship revocation provision. However, the press ignored the involvement of non-Muslim, white, Western-origin Canadians in terrorist acts and interpreted the measure as one that was mostly affecting Canadian Muslims. Thus, despite advocating for equal citizenship in principle, in their writing and reporting practice, Canadian newspapers constructed Canadian Muslims as sus- picious and less Canadian nonetheless. Keywords: Muslim Canadians; Citizenship; Terrorism; Canada; Revocation Résumé: Au sein de la version originale de la Loi renforçant la citoyenneté cana- dienne (2014), les citoyens canadiens ayant une double citoyenneté et ayant été condamnés pour haute trahison, pour terrorisme ou pour espionnage, auraient pu se faire révoquer leur citoyenneté canadienne. Dans cet article, nous étudions comment ce projet de loi fut discuté au sein de la presse canadienne. Nous cherchons à répondre à deux questions: Qui/quoi est perçu comme pouvant faire l’objet d’une révocation de citoyenneté? En quoi cela nous informe-t-il sur les orientations futures de la citoy- enneté canadienne? Nos résultats démontrent que les journaux canadiens sont plus critiques à l’égard de la révocation de la citoyenneté que positionnés en sa faveur. -

House of Commons Debates

House of Commons Debates VOLUME 146 Ï NUMBER 248 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 41st PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Tuesday, May 7, 2013 Speaker: The Honourable Andrew Scheer CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 16379 HOUSE OF COMMONS Tuesday, May 7, 2013 The House met at 10 a.m. EXPANSION AND CONSERVATION OF CANADA'S NATIONAL PARKS ACT Hon. Peter MacKay (for the Minister of the Environment) moved that Bill S-15, an act to amend the Canada National Parks Act Prayers and the Canada-Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Resources Accord Implementation Act and to make consequential amendments to the Canada Shipping Act, 2001, be read the first time. ROUTINE PROCEEDINGS (Motion agreed to and bill read the first time) Ï (1005) *** [English] PETITIONS GOVERNMENT RESPONSE TO PETITIONS GENETICALLY MODIFIED ALFALFA Mr. Tom Lukiwski (Parliamentary Secretary to the Leader of Mr. Earl Dreeshen (Red Deer, CPC): Mr. Speaker, I rise today the Government in the House of Commons, CPC): Mr. Speaker, to present a petition regarding genetically modified alfalfa. It is pursuant to Standing Order 36(8), I have the honour to table, in both signed by constituents in my riding and the surrounding area. official languages, the government's response to 13 petitions. NUCLEAR FUEL PROCESSING LICENCE *** Mr. Andrew Cash (Davenport, NDP): Mr. Speaker, I have two NAVIGABLE WATERS PROTECTION ACT petitions to present today. Mr. Craig Scott (Toronto—Danforth, NDP) moved for leave to Several months ago, the people in my riding of Davenport in introduce Bill C-506, an act to amend the Navigable Waters Toronto awoke to the fact that for 50 years now, GE Hitachi has been Protection Act (Don River).