From Endemically Proisrael to Unsympathetic: Australia's Middle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rhodesian Crisis in British and International Politics, 1964

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository THE RHODESIAN CRISIS IN BRITISH AND INTERNATIONAL POLITICS, 1964-1965 by CARL PETER WATTS A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Historical Studies The University of Birmingham April 2006 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. Abstract This thesis uses evidence from British and international archives to examine the events leading up to Rhodesia’s Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI) on 11 November 1965 from the perspectives of Britain, the Old Commonwealth (Canada, Australia, and New Zealand), and the United States. Two underlying themes run throughout the thesis. First, it argues that although the problem of Rhodesian independence was highly complex, a UDI was by no means inevitable. There were courses of action that were dismissed or remained under explored (especially in Britain, but also in the Old Commonwealth, and the United States), which could have been pursued further and may have prevented a UDI. -

JOSEPH MAX BERINSON B1932

THE LIBRARY AND INFORMATION SERVICE OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA J S BATTYE LIBRARY OF WEST AUSTRALIAN HISTORY Oral History Collection & THE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN PARLIAMENT PARLIAMENTARY ORAL HISTORY PROJECT Transcript of an interview with JOSEPH MAX BERINSON b1932 Access Research: Restricted until 1 January 2005 Publication: Restricted until 1 January 2005 Reference number 0H3102 Date of Interview 14 July 1993-7 July 1994 Interviewer Erica Harvey Duration 12 x 60 minute tapes Copyright Library Board of Western Australia The Library Board of WA 3 1111 02235314 6 INTRODUCTION This is an interview with Joseph (Joe) Berinson for the Battye Library and the Parliamentary Oral History Project. Joe Berinson was born to Sam Berinson and Rebecca Finklestein on 7 January 1932 in Highgate, Western Australia. He was educated at Highgate Primary School and Perth Modern School before gaining a Diploma of Pharmacy from the University of Western Australia in 1953. Later in life Mr Berinson undertook legal studies and was admitted to the WA Bar. He married Jeanette Bekhor in September 1958 and the couple have one son and three daughters Joining the ALP in 1953, Mr Berinson was an MHR in the Commonwealth Parliament from October 1969 to December 1975, where his service included Minister for the Environment from July to November 1975. In May 1980 he became an MLC in the Western Australian Parliament, where he remained until May 1989. Mr Berinson undertook many roles during his time in State Parliament, including serving as Attorney General from September 1981 to April 1983. The interview covers Mr Berinson's early family life and schooling, the migration of family members to Western Australia, and the influence and assistance of the Jewish community. -

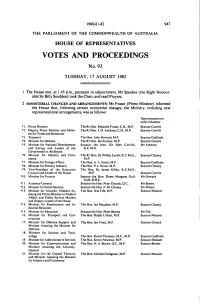

Votes and Proceedings

1980-81-82 947 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS No. 93 TUESDAY, 17 AUGUST 1982 1 The House met, at 1.45 p.m., pursuant to adjournment. Mr Speaker (the Right Honour- able Sir Billy Snedden) took the Chair, and read Prayers. 2 MINISTERIAL CHANGES AND ARRANGEMENTS: Mr Fraser (Prime Minister) informed the House that, following certain ministerial changes, the Ministry, including new representational arrangements, was as follows: Representationin other Chamber *1. Prime Minister The Rt Hon. Malcolm Fraser, C.H., M.P. Senator Carrick *2. Deputy Prime Minister and Minis- The Rt Hon. J. D. Anthony, C.H., M.P. Senator Carrick ter for Trade and Resources *3. Treasurer The Hon. John Howard, M.P. Senator Guilfoyle *4. Minister for Defence The Rt Hon. lan Sinclair, M.P. Senator Durack *5. Minister for National Development Senator the Hon. Sir John Carrick, Mr Anthony and Energy and Leader of the K.C.M.G. Government in the Senate *6. Minister for Industry and Com- The Rt Hon. Sir Phillip Lynch, K.C.M.G., Senator Chaney merce M.P. *7. Minister for Foreign Affairs The Hon. A. A. Street, M.P. Senator Guilfoyle *8. Minister for Primary Industry The Hon. P. J. Nixon, M.P. Senator Chancy *9. Vice-President of the Executive The Hon. Sir James Killen, K.C.M.G., Council and Leader of the House M.P. Senator Carrick *10. Minister for Finance Senator the Hon. Dame Margaret Guil- Mr Howard foyle, D.B.E. *11. Attorney-General Senator the Hon. -

GEOPOLITICS of the 2016 AUSTRALIAN DEFENSE WHITE PAPER and ITS PREDECESSORS Bert Chapman Purdue University, [email protected]

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Libraries Faculty and Staff choS larship and Research Purdue Libraries 4-25-2016 GEOPOLITICS OF THE 2016 AUSTRALIAN DEFENSE WHITE PAPER AND ITS PREDECESSORS Bert Chapman Purdue University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/lib_fsdocs Part of the Australian Studies Commons, Comparative Politics Commons, Defense and Security Studies Commons, Economic Policy Commons, Geography Commons, History of the Pacific Islands Commons, Industrial Organization Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, International Relations Commons, Military History Commons, Military Studies Commons, Peace and Conflict Studies Commons, Political Economy Commons, Political History Commons, Public Economics Commons, and the Public Policy Commons Recommended Citation Bert Chapman."Geopolitics of the 2016 Australian Defense White Paper and Its Predecessors." Geopolitics, History, and International Relations, 9 (1)(2017): 17-67. This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Geopolitics, History, and International Relations 9(1) 2017, pp. 17–67, ISSN 1948-9145, eISSN 2374-4383 GEOPOLITICS OF THE 2016 AUSTRALIAN DEFENSE WHITE PAPER AND ITS PREDECESSORS BERT CHAPMAN [email protected] Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN ABSTRACT. Australia released the newest edition of its Defense White Paper, describing Canberra’s current and emerging national security priorities, on February 25, 2016. This continues a tradition of issuing defense white papers since 1976. This work will examine and analyze the contents of this document as well as previous Australian defense white papers, scholarly literature, and political statements assess- ing their geopolitical significance. -

DALKIN, ROBERT NIXON (BOB) (1914–1991), Air Force Officer

D DALKIN, ROBERT NIXON (BOB) (1960–61), staff officer operations, Home (1914–1991), air force officer and territory Command (1957–59), and officer commanding administrator, was born on 21 February 1914 the RAAF Base, Williamtown, New South at Whitley Bay, Northumberland, England, Wales (1963). He had graduated from the RAF younger son of English-born parents George Staff College (1950) and the Imperial Defence Nixon Dalkin, rent collector, and his wife College (1962). Simultaneously, he maintained Jennie, née Porter. The family migrated operational proficiency, flying Canberra to Australia in 1929. During the 1930s bombers and Sabre fighters. Robert served in the Militia, was briefly At his own request Dalkin retired with a member of the right-wing New Guard, the rank of honorary air commodore from the and became business manager (1936–40) for RAAF on 4 July 1968 to become administrator W. R. Carpenter [q.v.7] & Co. (Aviation), (1968–72) of Norfolk Island. His tenure New Guinea, where he gained a commercial coincided with a number of important issues, pilot’s licence. Described as ‘tall, lean, dark including changes in taxation, the expansion and impressive [with a] well-developed of tourism, and an examination of the special sense of humour, and a natural, easy charm’ position held by islanders. (NAA A12372), Dalkin enlisted in the Royal Dalkin overcame a modest school Australian Air Force (RAAF) on 8 January education to study at The Australian National 1940 and was commissioned on 4 May. After University (BA, 1965; MA, 1978). Following a period instructing he was posted to No. 2 retirement, he wrote Colonial Era Cemetery of Squadron, Laverton, Victoria, where he Norfolk Island (1974) and his (unpublished) captained Lockheed Hudson light bombers on memoirs. -

With the End of the Cold War, the Demise of the Communist Party Of

A Double Agent Down Under: Australian Security and the Infiltration of the Left This is the Published version of the following publication Deery, Phillip (2007) A Double Agent Down Under: Australian Security and the Infiltration of the Left. Intelligence and National Security, 22 (3). pp. 346-366. ISSN 0268-4527 (Print); 1743-9019 (Online) The publisher’s official version can be found at Note that access to this version may require subscription. Downloaded from VU Research Repository https://vuir.vu.edu.au/15470/ A Double Agent Down Under: Australian Security and the Infiltration of the Left PHILLIP DEERY Because of its clandestine character, the world of the undercover agent has remained murky. This article attempts to illuminate this shadowy feature of intelligence operations. It examines the activities of one double agent, the Czech-born Maximilian Wechsler, who successfully infiltrated two socialist organizations, in the early 1970s. Wechsler was engaged by the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation. However, he was ‘unreliable’: he came in from the cold and went public. The article uses his exposés to recreate his undercover role. It seeks to throw some light on the recruitment methods of ASIO, on the techniques of infiltration, on the relationship between ASIO and the Liberal Party during a period of political volatility in Australia, and on the contradictory position of the Labor Government towards the security services. In the post-Cold War period the role of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) no longer arouses the visceral hostility it once did from the Left. The collapse of communism found ASIO in search of a new raison d’étre. -

The Interview-Document Nexus Recovering Histories of LGBTI Military Service in Australia Noah Riseman

The Interview-Document Nexus Recovering Histories of LGBTI Military Service in Australia noah riseman ABSTRACT Since 2014, I have been coordinating a team project documenting the history of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) military service in Australia. The project examines changing policies, practices, and most importantly, the lived experiences of LGBTI military service personnel from the end of the Second World War until the present. When we conceived this project, we expected that we would derive most policy information from records in the National Archives of Australia (NAA) and most information about lived expe- rience from a mixture of media reports and oral history interviews. What has astounded us, though, has been the extent to which several service members kept their own personal archives of documents – most of which related to their personal service and some of which did not appear in the NAA catalogue. In other instances, interview participants’ testimonies or personal documents raised topics that sent us to uncover other uncatalogued archival records. In this article, I draw on examples from our research project where this inter- view-document nexus proved fruitful in uncovering hitherto hidden histories of LGBTI military service in Australia. Rather than thinking about oral and archival sources as needing to be reconciled, conceptualizing them as a nexus generates new methodological possibilities to uncover new sources that inform each other, enriching both microhistories and grand narratives of the past. Archivaria The Journal of the Association of Canadian Archivists The Interview-Document Nexus 7 RÉSUMÉ Depuis 2014, je coordonne un projet d’équipe documentant l’his- toire du service militaire lesbien, gai, bisexuel, transgenre et intersexué (LGBTI) en Australie. -

Hansard 27 Nov 1997

27 Nov 1997 Ministerial Statement 4895 THURSDAY, 27 NOVEMBER 1997 properties; and (c) not permit the project to proceed without full community support. Petitions received. Mr SPEAKER (Hon. N. J. Turner, Nicklin) read prayers and took the chair at 9.30 a.m. SALARIES AND ALLOWANCES TRIBUNAL REPORT Hon. D. E. BEANLAND (Indooroopilly— PETITIONS Attorney-General and Minister for Justice) The Clerk announced the receipt of the (9.33 a.m.): On 19 August 1997 I tabled the following petitions— 17th report of the Salaries and Allowances Tribunal along with a copy of advice from the Solicitor-General relating to a dissenting report Political Advertising from Sir James Killen. In response to a From Mr Beattie (23 petitioners) request from Sir James, I now table a copy of requesting the House to immediately cease his letter to me on 10 September 1997 in politically motivated, taxpayer-funded which he responds to the Solicitor-General's advertising being used solely to promote the advice. I table also further advice dated 24 National and Liberal Parties and request November 1997 from the Solicitor-General on instead that the money go toward (a) this matter. improving funding for TAFE to give young people an opportunity to gain important skills training; (b) increasing resources to improve PAPER the police presence in Queensland towns and The following paper was laid on the communities; and (c) improving health services table— to reduce accident and emergency waiting Minister for Emergency Services and Minister times and ballooning waiting lists in our public for Sport (Mr Veivers)— hospitals. Response to Public Accounts Committee Report No. -

Commonwealth Arts Policy and Administration

Parliament of Australia Department of Parliamentary Services Parliamentary Library Information, analysis and advice for the Parliament BACKGROUND NOTE www.aph.gov.au/library 7 May 2009, 2008–09 Commonwealth arts policy and administration Dr John Gardiner-Garden Social Policy Section Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 1 From Deakin to McMahon.......................................................................................................... 1 The Whitlam Government .......................................................................................................... 1 The establishing of the Australia Council ......................................................................... 2 Other initiatives ................................................................................................................. 3 The Fraser Government .............................................................................................................. 4 Initial policies .................................................................................................................... 4 Reviews and reports .......................................................................................................... 5 Other initiatives ................................................................................................................. 8 The Hawke Government ............................................................................................................ -

Constitutional Convention

CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION [2nd to 13th FEBRUARY 1998] TRANSCRIPT OF PROCEEDINGS Wednesday, 11 February 1998 Old Parliament House, Canberra INTERNET The Proof and Official Hansards of the Constitutional Convention are available on the Internet http://www.dpmc.gov.au/convention http://www.aph.gov.au/hansard RADIO BROADCASTS Broadcasts of proceedings of the Constitutional Convention can be heard on the following Parliamentary and News Network radio stations, in the areas identified. CANBERRA 1440 AM SYDNEY 630 AM NEWCASTLE 1458 AM BRISBANE 936 AM MELBOURNE 1026 AM ADELAIDE 972 AM PERTH 585 AM HOBART 729 AM DARWIN 102.5 FM INTERNET BROADCAST The Parliamentary and News Network has established an Internet site containing over 120 pages of information. Also it is streaming live its radio broadcast of the proceedings which may be heard anywhere in the world on the following address: http://www.abc.net.au/concon CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION Old Parliament House, Canberra 2nd to 13th February 1998 Chairman—The Rt Hon. Ian McCahon Sinclair MP The Deputy Chairman—The Hon. Barry Owen Jones AO, MP ELECTED DELEGATES New South Wales Mr Malcolm Turnbull (Australian Republican Movement) Mr Doug Sutherland AM (No Republic—ACM) Mr Ted Mack (Ted Mack) Ms Wendy Machin (Australian Republican Movement) Mrs Kerry Jones (No Republic—ACM) Mr Ed Haber (Ted Mack) The Hon Neville Wran AC QC (Australian Republican Movement) Cr Julian Leeser (No Republic—ACM) Ms Karin Sowada (Australian Republican Movement) Mr Peter Grogan (Australian Republican Movement) Ms Jennie George -

Ministers for Foreign Affairs 1972-83

Ministers for Foreign Affairs 1972-83 Edited by Melissa Conley Tyler and John Robbins © The Australian Institute of International Affairs 2018 ISBN: 978-0-909992-04-0 This publication may be distributed on the condition that it is attributed to the Australian Institute of International Affairs. Any views or opinions expressed in this publication are not necessarily shared by the Australian Institute of International Affairs or any of its members or affiliates. Cover Image: © Tony Feder/Fairfax Syndication Australian Institute of International Affairs 32 Thesiger Court, Deakin ACT 2600, Australia Phone: 02 6282 2133 Facsimile: 02 6285 2334 Website:www.internationalaffairs.org.au Email:[email protected] Table of Contents Foreword Allan Gyngell AO FAIIA ......................................................... 1 Editors’ Note Melissa Conley Tyler and John Robbins CSC ........................ 3 Opening Remarks Zara Kimpton OAM ................................................................ 5 Australian Foreign Policy 1972-83: An Overview The Whitlam Government 1972-75: Gough Whitlam and Don Willesee ................................................................................ 11 Professor Peter Edwards AM FAIIA The Fraser Government 1975-1983: Andrew Peacock and Tony Street ............................................................................ 25 Dr David Lee Discussion ............................................................................. 49 Moderated by Emeritus Professor Peter Boyce AO Australia’s Relations -

The Early Fraser Ministry

Chapter 3 The Early Fraser Ministry James Killen, Minister for Defence Before retirement in 1979 I served my remaining four years in government service under James Killen as Minister and Malcolm Fraser as Prime Minister. At the end there was a well-intentioned, but publicly controversial and financially impractical, proposal from Ministers that I accept an extension beyond the compulsory retiring age of 65, which I declined. On retirement, I was able to turn to neglected family affairs, some writing and occasional involvement in seminars, and to take a short-term appointment nominated by the Prime Minister to review the Public Service in Fiji for that Government. Killen had held the Navy portfolio (now defunct) in the McMahon Ministry. After the now familiar formalities of inducting a new Minister into some classified areas which were subject to limited access, my first interest was to ascertain whether the reorganised system, and the policies put in place by his Labor predecessor, would be confirmed or wound back. Several matters hung in the air. Although amendments to the Defence Act had been proclaimed, they were not to come into effect until February 1976. The content of the Five Year programme would need to be reviewed by the Government, along with its underlying strategic assumptions. We could expect a call for a comprehensive review of those assumptions. Recommendations expected from the Hope Royal Commission affecting Defence would require decision. There was the Defence Force Academy project, several times deferred. There were inefficiencies, such as the low productivity of the civilian workforce in the Williamstown Dockyard managed by the Navy, which needed fixing.