Making Sense of Lost Highway Warren Buckland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Virtual Edition in Honor of the 74Th Festival

ARA GUZELIMIAN artistic director 0611-142020* Save-the-Dates 75th Festival June 10-13, 2021 JOHN ADAMS music director “Ojai, 76th Festival June 9-12, 2022 a Musical AMOC music director Virtual Edition th Utopia. – New York Times *in honor of the 74 Festival OjaiFestival.org 805 646 2053 @ojaifestivals Welcome to the To mark the 74th Festival and honor its spirit, we bring to you this keepsake program book as our thanks for your steadfast support, a gift from the Ojai Music Festival Board of Directors. Contents Thursday, June 11 PAGE PAGE 2 Message from the Chairman 8 Concert 4 Virtual Festival Schedule 5 Matthias Pintscher, Music Director Bio Friday, June 12 Music Director Roster PAGE 12 Ojai Dawns 6 The Art of Transitions by Thomas May 16 Concert 47 Festival: Future Forward by Ara Guzelimian 20 Concert 48 2019-20 Annual Giving Contributors 51 BRAVO Education & Community Programs Saturday, June 13 52 Staff & Production PAGE 24 Ojai Dawns 28 Concert 32 Concert Sunday, June 14 PAGE 36 Concert 40 Concert 44 Concert for Ojai Cover art: Mimi Archie 74 TH OJAI MUSIC FESTIVAL | VIRTUAL EDITION PROGRAM 2020 | 1 A Message from the Chairman of the Board VISION STATEMENT Transcendent and immersive musical experiences that spark joy, challenge the mind, and ignite the spirit. Welcome to the 74th Ojai Music Festival, virtual edition. Never could we daily playlists that highlight the 2020 repertoire. Our hope is, in this very modest way, to honor the spirit of the 74th have predicted how altered this moment would be for each and every MISSION STATEMENT Ojai Music Festival, to pay tribute to those who imagined what might have been, and to thank you for being unwavering one of us. -

Premiere / First Ever Performances in Germany LOST HIGHWAY Music

Premiere / First ever performances in Germany LOST HIGHWAY Music Theatre by Olga Neuwirth (*1968) Libretto by Elfriede Jelinek and Olga Neuwirth based on the script for the film by the same name (1997) by David Lynch and Barry Gifford Performed in English with German surtitles Conductor: Karsten Januschke Director: Yuval Sharon Set, Video and Lighting Designer: Jason H. Thompson, Kaitlyn Pietras Live Electronics: Markus Noisternig, Gilbert Nouno Sound Organiser: Norbert Ommer Costume Designer: Doey Lüthi Dramaturge: Stephanie Schulze Pete: John Brancy Fred: Jeff Burrell Renee / Alice: Elizabeth Reiter Mr. Eddy / Dick Laurent: David Moss Mystery Man: Rupert Enticknap Andy / Guard / Arnie: Samuel Levine Pete's Mother: Juanita Lascarro Pete's Father: Jörg Schäfer Ed / Detective Hank: Nicholas Bruder Al / Detective Lou / Prison Director: Jim Phetterplace jr. Doctor / The Man: Jeff Hallman Ensemble Modern With generous support from the Aventis Foundation, Kulturfond Frankfurt RheinMain and Frankfurt Patronatsverein – Sektion Oper David Lynch's film Lost Highway (1997) is a fascinating combination of psycho-thriller, horror and film noir. The Austrian composer Olga Neuwirth (*1968) and Literary Nobel Prize winner Elfriede Jelinek based their libretto on David Lynch and Barry Gifford's script. The World Premiere took place at the Steirische Herbst in Graz in 2003. Neuwirth developed a very ambitious way of telling the story about the „study of a person, who cannot come to terms with his fate“ (Gifford), combined with feverish changes in scene. Her score is extremely complex, combining intermedial threads with grand scale live electronics and video, which makes the fictionalised reality become almost virtual. „Dick Laurent is dead.“ The Jazz musician Fred hears this sentence over his intercom, and a door opens to a parallel universe. -

Digital Concert Hall

Digital Concert Hall Streaming Partner of the Digital Concert Hall 21/22 season Where we play just for you Welcome to the Digital Concert Hall The Berliner Philharmoniker and chief The coming season also promises reward- conductor Kirill Petrenko welcome you to ing discoveries, including music by unjustly the 2021/22 season! Full of anticipation at forgotten composers from the first third the prospect of intensive musical encoun- of the 20th century. Rued Langgaard and ters with esteemed guests and fascinat- Leone Sinigaglia belong to the “Lost ing discoveries – but especially with you. Generation” that forms a connecting link Austro-German music from the Classi- between late Romanticism and the music cal period to late Romanticism is one facet that followed the Second World War. of Kirill Petrenko’s artistic collaboration In addition to rediscoveries, the with the orchestra. He continues this pro- season offers encounters with the latest grammatic course with works by Mozart, contemporary music. World premieres by Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Olga Neuwirth and Erkki-Sven Tüür reflect Brahms and Strauss. Long-time compan- our diverse musical environment. Artist ions like Herbert Blomstedt, Sir John Eliot in Residence Patricia Kopatchinskaja is Gardiner, Janine Jansen and Sir András also one of the most exciting artists of our Schiff also devote themselves to this core time. The violinist has the ability to capti- repertoire. Semyon Bychkov, Zubin Mehta vate her audiences, even in challenging and Gustavo Dudamel will each conduct works, with enthusiastic playing, technical a Mahler symphony, and Philippe Jordan brilliance and insatiable curiosity. returns to the Berliner Philharmoniker Numerous debuts will arouse your after a long absence. -

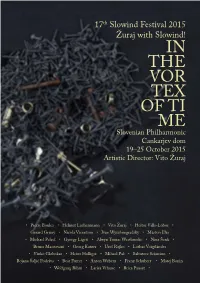

In the Vor Tex of Ti Me

17th Slowind Festival 2015 Žuraj with Slowind! IN THE VOR TEX OF TI Slovenian PhilharmonicME Cankarjev dom 19–25 October 2015 Artistic Director: Vito Žuraj • Pierre Boulez • Helmut Lachenmann • Vito Žuraj • Heitor Villa-Lobos • Gérard Grisey • Nicola Vicentino • Ivan Wyschnegradsky • Márton Illés • Michael Pelzel • György Ligeti • Alwyn Tomas Westbrooke • Nina Šenk • Bruno Mantovani • Georg Katzer • Uroš Rojko • Lothar Voigtländer • Vinko Globokar • Heinz Holliger • Mihael Paš • Salvatore Sciarrino • Bojana Šaljić Podešva • Beat Furrer • Anton Webern • Franz Schubert • Matej Bonin • Wolfgang Rihm • Larisa Vrhunc • Brice Pauset • Valued Listeners, It is no coincidence that we in Slowind decided almost three years ago to entrust the artistic direction of our festival to the penetrating, successful and (still) young composer Vito Žuraj. And it is precisely in the last three years that Vito has achieved even greater success, recently being capped off with the prestigious Prešeren Fund Prize in 2014, as well as a series of performances of his compositions at a diverse range of international music venues. Vito’s close collaboration with composers and performers of various stylistic orientations was an additional impetus for us to prepare the Slowind Festival under the leadership of a Slovenian artistic director for the first time! This autumn, we will put ourselves at the mercy of the vortex of time and again celebrate to some extent. On this occasion, we will mark the th th 90 birthday of Pierre Boulez as well as the 80 birthday of Helmut Lachenmann and Georg Katzer. In addition to works by these distinguished th composers, the 17 Slowind Festival will also present a range of prominent composers of our time, including Bruno Mantovani, Brice Pauset, Michael Pelzel, Heinz Holliger, Beat Furrer and Márton Illés, as well as Slovenian composers Larisa Vrhunc, Nina Šenk, Bojana Šaljić Podešva, Uroš Rojko, and Matej Bonin, and, of course, the festival’s artistic director Vito Žuraj. -

Olga Neuwirth, Enfant Terrible Van De Nieuwe Muziek 27 Info & Programma Focus on Olga Neuwirth, New Music Info & Programme 03 Enfant Terrible 29

OlgAFOCUS neuwirth KLOING! LE ENCANTADAS O LE AVVENTURE NEL MARE DELLE MERAVIGLIE PASCAL GALLOIS INHOUD CONTENT KLOING! FOCUS OLGA NEUWIRTH, ENFANT TERRIBLE VAN DE NIEUWE MUZIEK 27 INFO & PROGRAMMA FOCUS ON OLGA NEUWIRTH, NEW MUSIC INFO & PROGRAMME 03 ENFANT TERRIBLE 29 CREDITS 04 MUZIKAAL PORTRET 31 MUSICAL PORTRAIT 35 TOELICHTING 06 PROGRAMME NOTES 08 OLGA NEUWIRTH OVER HAAR COMPOSITIE LE ENCANTADAS 38 * OLGA NEUWIRTH ON HER COMPOSITION LE ENCANTADAS 42 LE ENCANTADAS O LE AVVENTURE NEL MARE DEL MERAVIGLIE BIOGRAFIEËN 46 BIOGRAPHIES 48 INFO & PROGRAMMA INFO & PROGRAMME 11 HOLLAND FESTIVAL 2016 52 CREDITS 12 WORD VRIEND BECOME A FRIEND 54 TOELICHTING 14 PROGRAMME NOTES 16 COLOFON COLOPHON 56 * PASCAL GALLOIS INFO, CREDITS & PROGRAMMA INFO, CREDITS & PROGRAMME 19 TOELICHTING 20 PROGRAMME NOTES 22 1 KLOING! NADAR ENSEMBLE MARINO FORMENTI 2 INFO PROGRAMMA ZO 5.6 PROGRAMME SUN 5.6 Stefan Prins (1979) aanvang starting time Mirror Box Extensions (2014/15) 15:00 3 pm ensemble, live-video en live electronics Nederlandse première locatie venue Dutch premiere Stadsschouwburg Amsterdam, Rabozaal pauze interval duur running time 2 uur 20 minuten, inclusief twee pauzes Olga Neuwirth (1968) 2 hours 20 minutes, including two Kloing! (2008) intervals Nederlandse première Dutch premiere inleiding introduction door by Michel Khalifa pauze interval 14:15 2.15 pm Michael Beil (1963)/Thierry Bruehl (1968) Bluff (2014/15) context scènische compositie voor ensemble met do 9.6, 12:30 & 13:30 live video en audio Thu 9.6, 12.30 pm & 1.30 pm scenic composition for ensemble with live Rijksmuseum, passage video and audio Lunchconcert: Vice Verses Nederlandse première Dutch premiere za 11.6, 14:00 Sat 11.6, 2 pm Festivalcentrum Stadsschouwburg Amsterdam Workshop Spielbar: speel eigentijdse muziek play contemporary music di 14.6, 20:00 Tue 14.6, 8 pm Festivalcentrum Stadsschouwburg Amsterdam Tijdens de voorstelling wordt gefilmd. -

Download Booklet

Photo: © Beatrix Neiss OLGA NEUWIRTH (*1968) Lost Highway (2002/03) Musiktheater Libretto Elfriede Jelinek und Olga Neuwirth nach einem Drehbuch von David Lynch und Barry Gifford CD 1 CD 2 1 Begin 1:04 10 Scene 3 2:24 1 Scene 6 0:56 10 Scene 9 3:56 2 Intro 2:26 11 Scene 4 2:26 2 Scene 6 2:12 11 Scene 9 2:47 3 Scene 1 9:53 12 Scene 5 2:11 3 Scene 6 3:23 12 Scene 10 3:04 4 Scene 1 2:40 13 Scene 5 1:10 4 Scene 6 2:03 13 Scene 10 1:46 5 Scene 2 1:33 14 Scene 5 1:28 5 Scene 7 2:24 14 Scene 11 2:43 6 Scene 2 1:39 15 Scene 5 5:08 6 Scene 7 1:46 15 Scene 11 0:47 7 Scene 2 2:16 16 Scene 5 0:33 7 Scene 8 2:04 16 Scene 11 5:08 8 Scene 3 3:37 17 Scene 6 2:51 8 Scene 8 2:14 17 Scene 12 3:04 9 Scene 3 6:32 9 Scene 9 2:47 TT: 49:58 TT: 43:12 Sounddesign: Olga Neuwirth and IEM* - Markus Noisternig, Gerhard Nierhaus, Robert Höldrich Audiotechnical concept: IEM* Sound engineer: Johannes Egger, Markus Noisternig (IEM*) Pre-recordings: Franz Hautzinger Quartertone-trumpet, Carsten Svanberg trombone, Robert Lepenik electronic guitar Publisher: Boosey & Hawkes. Bote & Bock GmbH & Co, Libretto © Rowohlt Theater Verlag Postproduction and mastering (IEM): Markus Noisternig, Olga Neuwirth Live-electronics, sound projection (IEM): Markus Noisternig, Thomas Musil, Robert Höldrich, Gerhard Nierhaus *IEM - Institut für Elektronische Musik und Akustik der Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst, Graz. -

2020 Music Director Matthias Pintscher and Artistic Director Chad Smith Announce Programming for the 74Th Festival June 11 to 14, 2020

2020 Music Director Matthias Pintscher and Artistic Director Chad Smith announce programming for the 74th Festival June 11 to 14, 2020 The 2020 Festival celebrates Pintscher as composer, conductor, and collaborator; welcomes the residency of his Ensemble intercontemporain (EIC) in its first Ojai appearance; and anticipates the return of the Calder Quartet Building connections between today’s most progressive composers and those from the past six centuries, the Festival explores the sonic worlds of Matthias Pintscher, seven-time Ojai Music Director Pierre Boulez, and composer Olga Neuwirth with highlights: • The 2020 Festival is anchored by Boulez’s Memoriale and sur Incises; the US Premiere of Olga Neuwirth’s Eleanor Suite, as well as performances of her In the realms of the unreal and Aello; the West Coast Premiere of Pintscher’s Nur, plus Uriel, Bereshit, and Rittrato di Gesualdo featured for the first time in Ojai; and programmed alongside works by Bach, Unsuk 1 Chin, Gesualdo, Ligeti, Mahler, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Steve Reich, Schubert, Varèse, and Zappa • US Premiere of the Genesis Cycle, with World Premiere EIC/Ojai co- commission of the “eighth day” The Flood by Toshio Hosakawa. Curated by Pintscher for EIC’s 40th birthday in 2017, the Genesis Cycle explores the Creation story and features works by composers from different coun- tries, including Mark Andre, Franck Bedrossian, Chaya Czernowin, Joan Magrané Figuera, Stefano Gervasoni, Toshio Hosakawa, Marko Nikodijevic, and Anna Thorvaldsdottir • Festival concludes with a Free Concert -

OLGA NEUWIRTH — Solo

OLGA NEUWIRTH Solo Klangforum Wien © Harald Hoffmann Olga Neuwirth (*1968 ) 1 CoronAtion I: io son ferito ahimè ( 2020 ) for percussion and sample 06:06 Commissioned by Klangforum Wien and funded by the Ernst von Siemens Musikstiftung 2 Weariness heals wounds I ( 2014 ) in memoriam Michael Glawogger for viola 13:08 3 Torsion ( 2003 ) for bassoon 14:10 4 Magic flu-idity ( 2018 ) for flute and Olivetti typewriter 14:45 5 Fumbling and Tumbling ( 2018 ) for trumpet 10:43 6 incidendo / fluido ( 2000 ) 1 Björn Wilker, percussion for piano with CD 12:46 2 Dimitrios Polisoidis, viola 3 Lorelei Dowling, bassoon 4 Vera Fischer, flute 5 Anders Nyqvist, trumpet TT 71:42 6 Florian Müller, piano 3 “I can’t make the real world any better than it is.” Olga Neuwirth This realisation, however, by no means Neuwirth calls it “Calamity-Music”; it is prevents the cosmopolitan from inter- dominated by her outrage which, how- fering with old (listening) habits, from ever, endows her with the power for provoking, polarising and of course creative expression. from taking a political stance. Her mu- sic contains deferrals, fractures, defor- “I know that the arts won’t change any- mations and associative links. Always thing, but art can point towards what in search of the fascinating Other, has become ossified and reveal the she explores the materials at hand – desolate state of society and politics. sounds, images and languages of var- I refuse to be yodelled away.” (Olga ious textures and from the most di- Neuwirth) verse backgrounds – and manages to link them without compromising their And so she produces continuously originality. -

Openspace Festival Calendar

2016 INTERSECTIO A POIN OF POIN A #CONCERTS#WORKSHOPS#MEETINGS#OPENSPACE FESTIVAL CALENDAR 20th – 25th May, 2016 n putting together the fourth festival, we interpretations; the environment itself have tried to present all the events as may be a stimulus to examine a known www.remusik.com part of a constantly developing creative compositional style from a different angle. In process. In this way, the organizers, guest this spirit, Livre pour quatuor révisé (author’s performers and composers become part edition 2015) by the recently deceased post- Iof a collective, live composition, laid out in war avant-garde maitre Pierre Boulez will Friday, 19.00 Festival Opening Day its own version of a musical score. But for receive its Russian premiere, performed by May 20th 2016 Erarta Stage this score to truly come alive and resonate quartet Diotima (France) as a tribute to the Ensemble for New Music Tallinn (Estonia) participants are necessary, and part of memory of one of the most important figures the responsibility falls to the audience. As in recent musical history. Their program a result, the following article is not only will also include compositions by Helmut Saturday, 11.00 The N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov a word of welcome, but also a guide for Lachenmann — a living legend who recently May 21st 2016 Saint Petersburg State Conservatory the listening participant and one of many celebrated his eighth decade and whose possible interpretations of the festival Meeting with Oscar Bianchi (Switzerland) creativity and energy could be envied by events. 13.00 The N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov conservatory students. -

La Poursuite I Vienne

iRCAM 06.07 LA POURSUITE I VIENNE LUNDi 13 NOVEMBRE Ircam - Centre20H30 Pompidou Ircam - Centre Pompidou Ircam - Centre Pompidou L’Ircam, association loi 1901, EQUIPES TECHNIQUES DU CONCERT organisme associé au Centre Pompidou, est subventionné IRCAM par le ministère de la Culture Jérémie Henrot, ingénieur du son et de la Communication Maxime Le Saux, régisseur son (Direction des affaires générales, Thomas Leblanc, régisseur Mission de la recherche et de la technologie THÉÂTRE DES BOUFFES DU NORD et Direction de la Musique, Michel Sorriaux, régisseur général de la danse, du théâtre Ircam - Centre Pompidouet des spectacles). Dans le cadre de son cercle d’entreprises, l’Ircam reçoit le soutien de : Ircam Conception graphique Ircam - CentreInstitut de recherchePompidou Aude Grandveau et coordination acoustique/musique 1 place Igor-Stravinsky 75004 Paris Tél. : +33 (0)1 44 78 48 43 www.ircam.fr Ircam - Centre Pompidou LA POURSUITE I VIENNE « La poursuite », nouveau cycle musical de l’Ircam au Théâtre des Bouffes du Nord, transforme le concert en un scénario sans interruption, tout à la fois poursuite lumière au théâtre, poursuite d’une tradition instrumentale s’élargissant par l’électronique, poursuite d’une pensée musicale par-delà les séparations historiques. Thomas Larcher, piano OLGA NEUWIRTH THOMAS LARCHER Réalisation informatique Incidendo/fluido Antennen… Requiem für H. musicale Frédéric Roskam ARNOLD SCHOENBERG [ CRÉATION FRANÇAISE Pièce pour piano opus 11/3 FRANZ SCHUBERT Pièce pour piano D946 Nr. 2 PRODUCTION IRCAM-CENTRE POMPIDOU. -

Olga Neuwirth (*1968 )

© Harald Hoffmann Olga Neuwirth (*1968 ) 1 CoronAtion I: io son ferito ahimè ( 2020 ) for percussion and sample 06:06 Commissioned by Klangforum Wien and funded by the Ernst von Siemens Musikstiftung 2 Weariness heals wounds I ( 2014 ) in memoriam Michael Glawogger for viola 13:08 3 Torsion ( 2003 ) for bassoon 14:10 4 Magic flu-idity ( 2018 ) for flute and Olivetti typewriter 14:45 5 Fumbling and Tumbling ( 2018 ) for trumpet 10:43 1 Björn Wilker, percussion 6 incidendo / fluido ( 2000 ) 2 Dimitrios Polisoidis, viola for piano with CD 12:46 3 Lorelei Dowling, bassoon 4 Vera Fischer, flute 5 Anders Nyqvist, trumpet TT 71:42 6 Florian Müller, piano 2 3 “I can’t make the real world any better than it is.” Olga Neuwirth This realisation, however, by no means pre- unusual, particular equation, the solution of vents the cosmopolitan from interfering which lies in itself. Neuwirth calls it “Calam- with old (listening) habits, from provoking, ity-Music”; it is dominated by her outrage polarising and of course from taking a po- which, however, endows her with the pow- litical stance. Her music contains deferrals, er for creative expression. fractures, deformations and associative links. Always in search of the fascinating “I know that the arts won’t change anything, Other, she explores the materials at hand – but art can point towards what has become sounds, images and languages of various ossified and reveal the desolate state of so- textures and from the most diverse back- ciety and politics. I refuse to be yodelled grounds – and manages to link them with- away.” (Olga Neuwirth) out compromising their originality. -

GABRIELA DIAZ Georgia Native Gabriela Diaz Began Her Musical Training at the Age of Five, Studying Piano with Her Mother, and the Next Year, Violin with Her Father

1 IMMERSION, ABSORPTION, CONNECTION. Composer Edgar Barroso presents a retrospective collection of works that explore his interest in contemporary sci- ence and technologies, social customs, spirituality, and more, using a variety of ensemble combinations and extended techniques for an array of textures and tonal colors. Commenting on prevailing social activities, Over-Proximity, a work in which the voices compete against each other’s seemingly disconnected phrases, addresses the hyper-connectivity and personal comparisons affected by social networking. The composer examines duration and perspective in works including Sketches of Briefness, Metric Ex- pansion of Space, and Aion, illustrating temporal relationships and the subjectivity of time. Scientific concepts inspire much of Barroso’s music, from the study of variation and change in Morphometrics to Echoic, which features the gamelan’s unique timbre and resonance spectrum. Barroso emphasizes balance, harmony, tranquility, and resolution in works like ACU and Ataraxia, while Noemata and Kuanasi Uato emphasize discord, struggle, and instability, evoking the hardships faced in his native Mexico. 2 KUANASI UATO Commissioned by the International Cervantino Festival, the name of this piece comes from an expression in the Purepecha language, Kuanasi Huato, which means “hill of frogs.” and describes the shape of a series of hills that look like many overlapped frogs. Kuanasi Huato is also the origin of Guanajuato, the name of a city in the center of Mexico, my native country. Because of the geographical characteristics of the city, one can only access it by going through tunnels that cross those hills. The transitions between the outside of the city and the arrival to it is quite unique.