355 Oscar Hammerstein Ii and the Performativity of Race

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

County Theater ART HOUSE

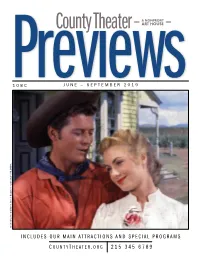

A NONPROFIT County Theater ART HOUSE Previews108C JUNE – SEPTEMBER 2019 Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones in Rodgers & Hammerstein’s OKLAHOMA! & Hammerstein’s in Rodgers Gordon MacRae and Shirley Jones INCLUDES OUR MAIN ATTRACTIONS AND SPECIAL PROGRAMS C OUNTYT HEATER.ORG 215 345 6789 Welcome to the nonprofit County Theater The County Theater is a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501(c)(3) organization. Policies ADMISSION Children under 6 – Children under age 6 will not be admitted to our films or programs unless specifically indicated. General ............................................................$11.25 Late Arrivals – The Theater reserves the right to stop selling Members ...........................................................$6.75 tickets (and/or seating patrons) 10 minutes after a film has Seniors (62+) & Students ..................................$9.00 started. Matinees Outside Food and Drink – Patrons are not permitted to bring Mon, Tues, Thurs & Fri before 4:30 outside food and drink into the theater. Sat & Sun before 2:30 .....................................$9.00 Wed Early Matinee before 2:30 ........................$8.00 Accessibility & Hearing Assistance – The County Theater has wheelchair-accessible auditoriums and restrooms, and is Affiliated Theater Members* ...............................$6.75 equipped with hearing enhancement headsets and closed cap- You must present your membership card to obtain membership discounts. tion devices. (Please inquire at the concession stand.) The above ticket prices are subject to change. Parking Check our website for parking information. THANK YOU MEMBERS! Your membership is the foundation of the theater’s success. Without your membership support, we would not exist. Thank you for being a member. Contact us with your feedback How can you support or questions at 215 348 1878 x115 or email us at COUNTY THEATER the County Theater? MEMBER [email protected]. -

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

Ferenc Molnar

L I L I O M A LEGEND IN SEVEN SCENES BY FERENC MOLNAR EDITED AND ADAPTED BY MARK JACKSON FROM AN ENGLISH TEXT BY BENJAMIN F. GLAZER v2.5 This adaptation of Liliom Copyright © 2014 Mark Jackson All rights strictly reserved. For all inquiries regarding production, publication, or any other public or private use of this play in part or in whole, please contact: Mark Jackson email: [email protected] www.markjackson-theatermaker.com CAST OF CHARACTERS (4w;4m) Marie / Stenographer Julie / Louise Mrs Muskat Liliom Policeman / The Guard Mrs Hollunder / The Magistrate Ficsur / A Poorly Dressed Man Wolf Beifeld / Linzman / Carpenter / A Richly Dressed Man SCENES (done minimally and expressively) FIRST SCENE — A lonely place in the park. SECOND SCENE — Mrs. Hollunder’s photographic studio. THIRD SCENE — Same as scene two. FOURTH SCENE — A railroad embankment outside the city. FIFTH SCENE — Same as scene two SIXTH SCENE — A courtroom in the beyond. SEVENTH SCENE — Julie’s garden, sixteen years later. A NOTE (on time & place) The current draft retains Molnar’s original 1909 Budapest setting. With minimal adjustments the play could easily be reset in early twentieth century America. Though I wonder whether certain of the social attitudes—toward soldiers, for example— would transfer neatly, certainly an American setting could embody Molnar’s complex critique of gender, class, and racial tensions. That said, retaining Molnar’s original setting perhaps now adds to his intention to fashion an expressionist theatrical legend, while still allowing for the strikingly contemporary themes that prompted me to write this adaptation—among them how Liliom struggles and fails to change in the face of economic and social flux; that women run the businesses, Heaven included; and Julie’s independent, confidently anti-conventional point of view. -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1950S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1950s Page 86 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1950 A Dream Is a Wish Choo’n Gum I Said my Pajamas Your Heart Makes / Teresa Brewer (and Put On My Pray’rs) Vals fra “Zampa” Tony Martin & Fran Warren Count Every Star Victor Silvester Ray Anthony I Wanna Be Loved Ain’t It Grand to Be Billy Eckstine Daddy’s Little Girl Bloomin’ Well Dead The Mills Brothers I’ll Never Be Free Lesley Sarony Kay Starr & Tennessee Daisy Bell Ernie Ford All My Love Katie Lawrence Percy Faith I’m Henery the Eighth, I Am Dear Hearts & Gentle People Any Old Iron Harry Champion Dinah Shore Harry Champion I’m Movin’ On Dearie Hank Snow Autumn Leaves Guy Lombardo (Les Feuilles Mortes) I’m Thinking Tonight Yves Montand Doing the Lambeth Walk of My Blue Eyes / Noel Gay Baldhead Chattanoogie John Byrd & His Don’t Dilly Dally on Shoe-Shine Boy Blues Jumpers the Way (My Old Man) Joe Loss (Professor Longhair) Marie Lloyd If I Knew You Were Comin’ Beloved, Be Faithful Down at the Old I’d Have Baked a Cake Russ Morgan Bull and Bush Eileen Barton Florrie Ford Beside the Seaside, If You were the Only Beside the Sea Enjoy Yourself (It’s Girl in the World Mark Sheridan Later Than You Think) George Robey Guy Lombardo Bewitched (bothered If You’ve Got the Money & bewildered) Foggy Mountain Breakdown (I’ve Got the Time) Doris Day Lester Flatt & Earl Scruggs Lefty Frizzell Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo Frosty the Snowman It Isn’t Fair Jo Stafford & Gene Autry Sammy Kaye Gordon MacRae Goodnight, Irene It’s a Long Way Boiled Beef and Carrots Frank Sinatra to Tipperary -

German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.202.58, on 26 Sep 2021 at 08:28:39, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://www.cambridge.org/core/product/2CC6B5497775D1B3DC60C36C9801E6B4 German Operetta on Broadway and in the West End, 1900–1940 Academic attention has focused on America’sinfluence on European stage works, and yet dozens of operettas from Austria and Germany were produced on Broadway and in the West End, and their impact on the musical life of the early twentieth century is undeniable. In this ground-breaking book, Derek B. Scott examines the cultural transfer of operetta from the German stage to Britain and the USA and offers a historical and critical survey of these operettas and their music. In the period 1900–1940, over sixty operettas were produced in the West End, and over seventy on Broadway. A study of these stage works is important for the light they shine on a variety of social topics of the period – from modernity and gender relations to new technology and new media – and these are investigated in the individual chapters. This book is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core at doi.org/10.1017/9781108614306. derek b. scott is Professor of Critical Musicology at the University of Leeds. -

HERRICK GOLDMAN LIGHTING DESIGNER Website: HG Lighting Design Inc

IGHTING ESIGNER HERRICK GOLDMAN L D Website: HG Lighting Design inc. Phone: 917-797-3624 www.HGLightingDesign.com 1460 Broadway 16th floor E-mail: [email protected] New York, NY 10036 Honors & Awards: •2009 LDI Redden Award for Excellence in Theatrical Design •2009 Henry Hewes (formerly American Theatre Wing) Nominee for “Rooms a Rock Romance” •2009 ISES Big Apple award for Best Event Lighting •2010 Live Design Excellence award for Best Theatrical Lighting Design •2011 Henry Hewes Nominee for Joe DiPietro’s “Falling for Eve” Upcoming: Alice in Wonderland Pittsburgh Ballet, Winter ‘17 Selected Experience: •New York Theater (partial). Jason Bishop The New Victory Theater, Fall ‘16 Jasper in Deadland Ryan Scott Oliver/ Brandon Ivie dir. Prospect Theater Company Off-Broadway, NYC March ‘14 50 Shades! the Musical (Parody) Elektra Theatre Off-Broadway, NYC Jan ‘14 Two Point Oh 59 e 59 theatres Off-Broadway, NYC Oct. ‘13 Amigo Duende (Joshua Henry & Luis Salgado) Museo Del Barrio, NYC Oct. ‘12 Myths & Hymns Adam Guettel Prospect Theater co. Off-Broadway, NYC Jan. ‘12 Falling For Eve by Joe Dipietro The York Theater, Off-Broadway NYC July. ‘10 I’ll Be Damned The Vineyard Theater, Off-Broadway NYC June. ‘10 666 The Minetta Lane Theater Off-Broadway, NYC March. ‘10 Loaded Theater Row Off-Broadway, NYC Nov. ‘09 Flamingo Court New World Stages Off-Broadway, NYC June ‘09 Rooms a Rock Romance Directed by Scott Schwartz, New World Stages, NYC March. ‘09 The Who’s Tommy 15th anniversary concert August Wilson Theater, Broadway, NYC Dec. ‘08 Flamingo Court New World Stages Off-Broadway, NYC July ‘08 The Last Starfighter (The musical) Theater @ St. -

The Sleeping Beauty Untouchable Swan Lake In

THE ROYAL BALLET Director KEVIN O’HARE CBE Founder DAME NINETTE DE VALOIS OM CH DBE Founder Choreographer SIR FREDERICK ASHTON OM CH CBE Founder Music Director CONSTANT LAMBERT Prima Ballerina Assoluta DAME MARGOT FONTEYN DBE THE ROYAL BALLET: BACK ON STAGE Conductor JONATHAN LO ELITE SYNCOPATIONS Piano Conductor ROBERT CLARK ORCHESTRA OF THE ROYAL OPERA HOUSE Concert Master VASKO VASSILEV Introduced by ANITA RANI FRIDAY 9 OCTOBER 2020 This performance is dedicated to the late Ian Taylor, former Chair of the Board of Trustees, in grateful recognition of his exceptional service and philanthropy. Generous philanthropic support from AUD JEBSEN THE SLEEPING BEAUTY OVERTURE Music PYOTR IL’YICH TCHAIKOVSKY ORCHESTRA OF THE ROYAL OPERA HOUSE UNTOUCHABLE EXCERPT Choreography HOFESH SHECHTER Music HOFESH SHECHTER and NELL CATCHPOLE Dancers LUCA ACRI, MICA BRADBURY, ANNETTE BUVOLI, HARRY CHURCHES, ASHLEY DEAN, LEO DIXON, TÉO DUBREUIL, BENJAMIN ELLA, ISABELLA GASPARINI, HANNAH GRENNELL, JAMES HAY, JOSHUA JUNKER, PAUL KAY, ISABEL LUBACH, KRISTEN MCNALLY, AIDEN O’BRIEN, ROMANY PAJDAK, CALVIN RICHARDSON, FRANCISCO SERRANO and DAVID YUDES SWAN LAKE ACT II PAS DE DEUX Choreography LEV IVANOV Music PYOTR IL’YICH TCHAIKOVSKY Costume designer JOHN MACFARLANE ODETTE AKANE TAKADA PRINCE SIEGFRIED FEDERICO BONELLI IN OUR WISHES Choreography CATHY MARSTON Music SERGEY RACHMANINOFF Costume designer ROKSANDA Dancers FUMI KANEKO and REECE CLARKE Solo piano KATE SHIPWAY JEWELS ‘DIAMONDS’ PAS DE DEUX Choreography GEORGE BALANCHINE Music PYOTR IL’YICH TCHAIKOVSKY -

Rodgers & Hammerstein

Connect the Devon Energy Presents Dots to Find Lyric Theatre’s the Castle! CinderellaA Literary Tale Interactive Rodgers & Hammerstein The music of Cinderella was composed by Richard Rodgers. The lyrics to the songs and book (script) were written by Oscar Hammerstein II. Originally presented on television in 1957 starring Julie Andrews (pictured below), Rodgers and Hammerstein’s Cinderella was the most widely viewed program in the history of the medium. Andrews starred in many musicals and movies, such as The Sound of Music, Camelot, and The Princess Diaries. Music by Richard Rodgers Book & Lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II After long and highly distinguished careers with Study Guide Recommended for Children of All Ages other writing partners, Richard Rodgers (composer, Lyric’s Cinderella - A Literary Tale Interactive is a thrilling program 1902-1979) and Oscar Hammerstein II (librettist/ offering an original take on a familiar story. You will visit with favorite lyricist, 1895-1960), also known as R&H, joined characters: the gracious Cinderella, the charming Prince, and the forces in 1943 to create the most consistently fruitful evil Stepsisters. Through the music and dialogue of Rodgers and and successful partnership in the American musical Hammerstein, you will learn fun and important literary terms and theatre. Oklahoma!, the first Rodgers & Hammerstein concepts. musical, was also the first of a new genre, the musical play! Other R&H Musicals You May Know: Carousel, South Pacific, The King and I,and The Sound of Music Carolyn Watson THE Wilshire Rural Oklahoma McGee Charitable Source: www.rnh.com Community Foundation FOUNDATION Foundation LYRIC IS OKLAHOMA’S LEADING PROFESSIONAL THEATRE COMPANY and Seek & has been producing classic and contemporary musicals featuring both nationally Literature Plot Diagram known Broadway stars and local favorites for over 50 years. -

Here Are a Number of Recognizable Singers Who Are Noted As Prominent Contributors to the Songbook Genre

Music Take- Home Packet Inside About the Songbook Song Facts & Lyrics Music & Movement Additional Viewing YouTube playlist https://bit.ly/AllegraSongbookSongs This packet was created by Board-Certified Music Therapist, Allegra Hein (MT-BC) who consults with the Perfect Harmony program. About the Songbook The “Great American Songbook” is the canon of the most important and influential American popular songs and jazz standards from the early 20th century that have stood the test of time in their life and legacy. Often referred to as "American Standards", the songs published during the Golden Age of this genre include those popular and enduring tunes from the 1920s to the 1950s that were created for Broadway theatre, musical theatre, and Hollywood musical film. The times in which much of this music was written were tumultuous ones for a rapidly growing and changing America. The music of the Great American Songbook offered hope of better days during the Great Depression, built morale during two world wars, helped build social bridges within our culture, and whistled beside us during unprecedented economic growth. About the Songbook We defended our country, raised families, and built a nation while singing these songs. There are a number of recognizable singers who are noted as prominent contributors to the Songbook genre. Ella Fitzgerald, Fred Astaire, Rosemary Clooney, Nat King Cole, Sammy Davis Jr., Judy Garland, Billie Holiday, Lena Horne, Al Jolson, Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra, Mel Tormé, Margaret Whiting, and Andy Williams are widely recognized for their performances and recordings which defined the genre. This is by no means an exhaustive list; there are countless others who are widely recognized for their performances of music from the Great American Songbook. -

What's the Use of Wondering If He's Good Or Bad?: Carousel and The

What’s the Use of Wondering if He’s Good or Bad?: Carousel and the Presentation of Domestic Violence in Musicals. Patricia ÁLVAREZ CALDAS Universidad de Santiago de Compostela [email protected] Recibido: 15.09.2012 Aceptado: 30.09.2012 ABSTRACT The analysis of the 1956 film Carousel (Dir. Henry King), which was based on the 1945 play by Rodgers and Hammerstein, provides a suitable example of a musical with explicit allusions to male physical aggression over two women: the wife and the daughter. The issue of domestic violence appears, thus, in a film genre in which serious topics such as these are rarely present. The film provide an opportunity to study how the expectations and the conventions brought up by this genre are capable of shaping and transforming the presentation of Domestic Violence. Because the audience had to sympathise with the protagonists, the plot was arranged to fulfil the conventional pattern of a romantic story inducing audiences forget about the dark themes that are being portrayed on screen. Key words: Domestic violence, film, musical, cultural studies. ¿De qué sirve preocuparse por si es bueno o malo?: Carrusel y la presentación de la violencia doméstica en los musicales. RESUMEN La película Carrusel (dirigida por Henry King en 1956 y basada en la obra de Rodgers y Hammerstein de 1945), nos ofrece un gran ejemplo de un musical que realiza alusiones explícitas a las agresiones que ejerce el protagonista masculino sobre su esposa y su hija. El tema de la violencia doméstica aparece así en un género fílmico en el que este tipo de tratamientos rara vez están presentes. -

Show Boat Little Theatre on the Square

Eastern Illinois University The Keep 1967 Shows Programs 1967 Summer 7-24-1967 Show Boat Little Theatre on the Square Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/little_theatre_1967_programs Part of the Theatre History Commons Recommended Citation Little Theatre on the Square, "Show Boat" (1967). 1967 Shows Programs. 8. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/little_theatre_1967_programs/8 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the 1967 at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in 1967 Shows Programs by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "Central Illinois' Only Equity Stur lZlusic and Drama Theatre" Eleventh Season a May - October 1967 Sullivan, Illinois 6uy S. Little, Jr. Presents BRUCE YARNELL in "HOVJ BOAT" July 25 - August 6, 1967 6y S. littleI Jr. PRESBNTS BRUCE YARNELL "SHOI BOAT' Music by JEROME KERN Book and Lyrics by OSCAR HAMMERSTEIN 2nd Based on the novel "Show BoaP by EDNA FERBER wlth MARCIA KIN6 Jetill Little, Art KQSUI~John KelsoI Stwe S-:. EDWARD PIERSON and BUTTERFLY MaQUEEW Directed by ROBERT BAKER ::.:;:' Choreography by GEORGE BUNT Musical Direction by DONALD W. CHA@ Assistant Murical Direction by ROIBRT MCWCapW . .* Scenery ~esi~nedby KENNETH E. LlQ%f@. Production Stag. Manamr Assistant Stage Mmapr RICHARD GHWON BILL TSOKOS =MEN- Wk ENTIRE PRODUCTION UNDER THE SUPERVISION OT 5 :. --, . ' I CAST , , -: Captain Andy.. ..........................., ....................... ART -1 Ellie ......................................................... -

November 13 – the Best of Broadway

November 13 – The Best of Broadway SOLOISTS: Bill Brassea Karen Babcock Brassea Rebecca Copley Maggie Spicer Perry Sook PROGRAM Broadway Tonight………………………………………………………………………………………………Arr. Bruce Chase People Will Say We’re in Love from Oklahoma……….…..Rodgers & Hammerstein/Robert Bennett Try to Remember from The Fantasticks…………………………………………………..Jack Elliot/Jack Schmidt Can’t Help Lovin’ Dat Man from Show Boat……………………………Oscar Hammerstein/Jerome Kern/ Robert Russell Bennett Gus: The Theatre Cat from Cats……………………………………….……..…Andrew Lloyd Webber/T.S. Eliot Selections from A Chorus Line…………………………………….……..Marvin Hamlisch/Arr. Robert Lowden Glitter and Be Gay from Candide…………………….………………………………………………Leonard Bernstein Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off from Shall We Dance…….…….……………………George & Ira Gershwin Impossible Dream from Man of La Mancha………………………………………….…Mitch Leigh/Joe Darion Mambo from Westside Story……………………………………………..…………………….…….Leonard Bernstein Somewhere from Westside Story……………………………………….…………………….…….Leonard Bernstein Intermission Seventy-Six Trombones from The Music Man………………………….……………………….Meredith Willson Before the Parade Passes By from Hello, Dolly!……………………………John Herman/Michael Stewart Vanilla Ice Cream from She Loves Me…………..…………....…………………….Sheldon Harnick/Jerry Bock Be a Clown from The Pirate..…………………………………..………………………………………………….Cole Porter Summer Time from Porgy & Bess………………………………………………………….………….George Gershwin Move On from Sunday in the Park with George………….……..Stephen Sondheim/Michael Starobin The Grass is Always Greener from Woman of the Year………….John Kander/Fred Ebb/Peter Stone Phantom of the Opera Overture……………………………………………………………….Andrew Lloyd Webber Music of the Night from Phantom of the Opera…….………………………………….Andrew Lloyd Webber Love Never Dies from Love Never Dies………………..…..……………………………….Andrew Lloyd Webber Over the Rainbow from The Wizard of Oz….……………………………………….Harold Arlen/E.Y. Harburg Arr. Mark Hayes REHEARSALS: Mon., Oct. 17 7 p.m.